“Beyond the Aggressives” Has Arrived Just On Time For Black Trans Masc Representation

One of the first times I could distinctly recall seeing a version of myself was in the documentary The Aggressives. I was only a child, but I immediately understood that the subjects who poured out the intimacies of their lives in this film were future renditions of me. They were gender non-conforming Black people who at the time thought of themselves as women and outwardly presented themselves as masculine.

Throughout the film, the legitimacy of their masculinity was called into question because of how they carried themselves, or because of the types of women they were attracted to. Many of them were trans, and that was readily accepted despite their lack of access or use of hormones. A few of them conveyed their disdain for being regarded as similar to cis men, but they also didn’t view their womanhood as rigid or non-malleable.

At the time, this documentary was one of the only real life depictions of Black trans masc people that a child like me could grasp onto. I had never really come across representations of myself in mainstream media. The very few available depictions of trans masculine narratives were laden with trauma and violence, like Boys Don’t Cry, or they were exploitative. But for many like myself, The Aggressives was the first relatable illustration of gender disruptors that were painted in a more complex, nuanced, and humane fashion.

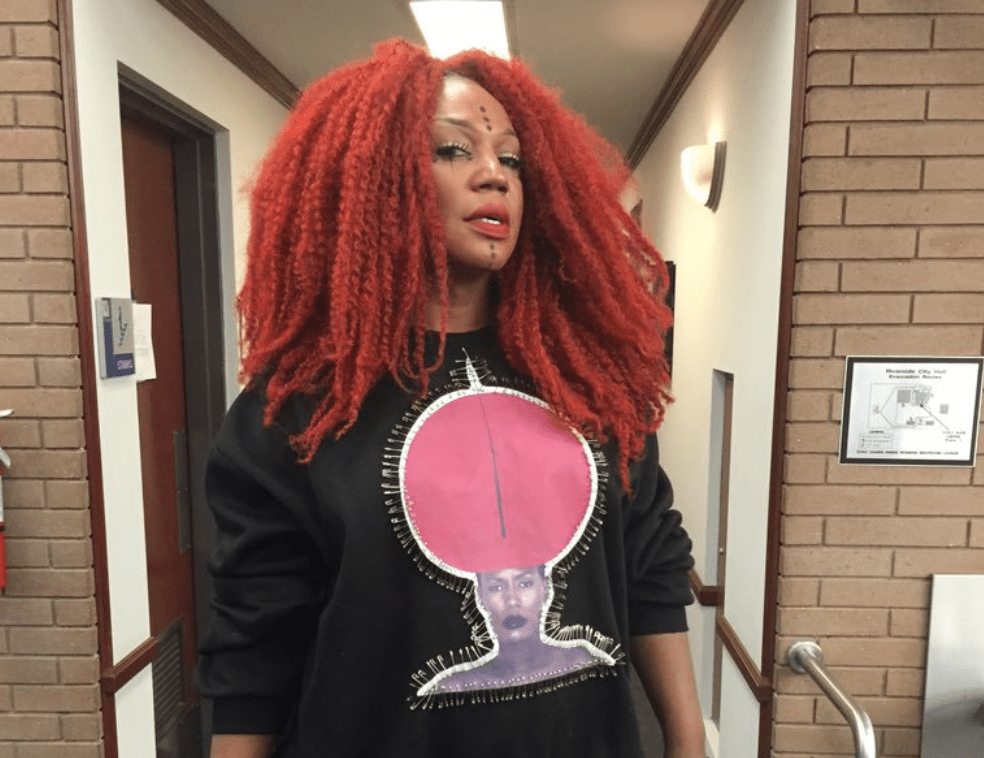

We are reintroduced to many of the main cast from the original film in Beyond the Aggressives. In an almost “where are they now” fashion, we catch up with Kisha, Trevon, Octavio, and Chin as they traverse hardships related to racism, starting families, and growing older. Some of the original film’s subjects, including Marquise Vilson who does not make an appearance in the follow-up, have gone into modeling, or have budding TV and movie careers. But there remains a dearth of trans masc representation in media, whether it be in our books or on our screens. While there have been radical changes since the likes of Paris is Burning, transgender people have remained underrepresented and misrepresented across media overall, and trans masc representation is minimal.

The 90s are long gone; we have since had Sense 8, Pose, Orange is the New Black, Transparent, and a range of shows that are trans inclusive. But having more representation is not enough for those being portrayed. This visibility has not shifted or improved most trans lives, as many portrayals make spectacles of the trans community, specifically of trans women.

There’s no competition between trans feminine and trans masculine people. The systematic designs that sensationalize trans women are the very same structures that erase trans masc people. Within our toxic and sexist culture, we are quick to condemn the (outwardly) feminine. There’s this element of shock and condescension with trans women; why would anyone want to give up their manhood? All the while, trans men are impacted by this same misogyny, and find their identities as well as their experiences erased. We are reduced to our genitals, thus, according to cisheteronormative society, our identities are not considered real or legitimate masculinity. If we can never be “real,” we don’t exist, and the menacing violence enacted upon us and our bodies therefore also does not exist.

These prejudices are reflected in our media. While trans feminine characters were often reduced to villains, there was a visible absence of trans masc main characters, especially of Black and brown trans masculine characters. But like our sisters, the little representation we had did not fare well for trans masculine people. Trans masculine people who were visible were sensationalized in exploitative talk show appearances, like Reno, the Black trans man who appeared on Jerry Springer. For a long time, talk shows like this were our only representation.

And yet, as trans masc representation has increased in recent years, it’s important to remember the limits of that success. If there is any testament that visibility has not always equated to positivity, look no further than The Aggressives and its follow up.

The subjects of the original documentary were all given a platform to raise their notability, but as they explaine in Beyond the Aggressives, their new celebrity didn’t shield them from the injustices they experienced due to their gender identities or race. After The Aggressives, Trevon’s celebrity helped him land modeling gigs, like Barney’s 2014 campaign. And yet, by the time of filming Beyond the Aggressives, Trevon conveyed the difficulty he experienced while attempting to find an OBGYN office that did not misgender him. Also by the time of filming of the follow up, Chin’s race and gender were both villainized and victimized. Due to a racist error made on the part of the government, Chin was detained at an I.C.E. Detention center for almost two years, where he was subjected to solitary confinement because he was trans.

Beyond the Aggressives shows us how far we have come in terms of portraying trans masc people, but we still have such a long way to go. We can now find ourselves in TV and movies other than documentaries, but at what cost? Many trans masc people have a difficulty relating to trans characters on-screen because those characters are so frequently objectified for their bodies. Trans masc characters are usually only semi-regular characters or have secondary storylines. And even when they are the lead – like Elliot Page in The Umbrella Academy or Brian Michael Smith in Lonestar 911 – they are tasked with representing us alone. When was the last time you’ve seen more than two or three trans men on the screen at one time? And all as main characters? Or characters that evolve beyond medical narrative or two-dimensional standards we’ve witnessed thus far?

According to GLAAD’s Where We Are on TV report, there were only a little over 11 trans masc characters on TV during the 2022-23 year. That is less than the 14+ characters of the previous year.

How do we change this? And how can we make sure this change includes an increase in quality as well as quantity?

The best kind of change comes from within. And from what I can ascertain, change is ahead of us. It begins by diversifying our writing rooms, placing the pen in the hands of trans masc people who are longing for the opportunity to give power to our stories from an authentic lens. It includes hiring trans masculine actors to play explicitly trans masculine roles and roles that were initially written for cis men. There are an abundance of budding trans actors, including myself, who didn’t believe that certain careers, like acting, were possibilities, due to our consistent absence on TV screens. Let’s continue to change that.

When it comes to positively amplifying our visibility, Beyond the Aggressives is just on time. And while the original film didn’t grant the subjects access to any special treatment, or indefinite resources, in hindsight, Chin’s legacy and his connection to the filmmakers helped to expedite his unfortunate and untimely legal case. Daniel Peddle and his team were able to find appropriate legal representation that eventually helped Chin to have his past charges dropped. And yet, even after his case’s media exposure, he spent many months devoid of the agency to take care of himself while he waited for his new IDs to be issued by the government.

As we can see, visibility is a two-sided coin, but if we put the mic, the pen, or even the camera in the hands of those sharing their stories, we get a more authentic narrative, more diverse characters, and more nuanced storytelling. Trans awareness has ballooned following many years of anti-trans bills, leaving a negative impression upon those who don’t know a trans person personally. We need more trans masculine produced stories that are relatable and are tools in combating the falsehoods brought about from said bills.

Kisha, Trevon, Octavio and Chin are all more than just their gender expressions or their sexualities. Having witnessed their plights as teenagers, now we bear witness to their more mature versions as they navigate aging, healthcare (or lack thereof), parenthood, incarceration, and of course, gender challenges that are not just relatable to us, but that are parallel to various lives across the country.

The tribulations we witness in Beyond the Aggressives show why our stories deserve more airtime: to validate our existence and to humanize our experiences.

Beyond the Aggressives has just concluded a brief theatrical run and will stream on Paramount+ sometime next year.

Daniel Sea on Max’s Return to “The L Word: Generation Q”

It’s hard to find a balance between skepticism and positivity. It’s hard to know when change is superficial, marginal, placating, and when it’s substantive. I have such big dreams for our world — on-screen and off. I vibrate with frustration, I vibrate with hope.

As you probably know, Max — one of the most meaningful and maltreated characters on the original series — has come back to The L Word universe for a one episode appearance on Gen Q. When we last saw Max, he was pregnant and alone, mocked by friends who were never friendly. He was a cautionary tale of what happens when transmasculine people dare to assert their genders. All the while, Daniel Sea, the real trans person playing the character, faced similar treatment behind the scenes.

When I first reached out to Daniel three years ago, I felt like there was a story that wasn’t being told. The initial Gen Q press tours were all about how much progress the show had made since the original series — while repeating the mistake of misgendering Daniel. Progress is rarely as linear as we hope, nor is it possible without an honest reckoning with the past. References to Daniel’s transness on Instagram were vague but they were there if anyone cared to look. Most people didn’t care.

Throughout the process of our initial conversations and our formal interview, I was lucky enough to get to know Daniel, the person. I wanted clarity on their gender, but I learned so much more. One of the highlights of my time writing for Autostraddle was doing that interview, getting to play a part in deepening our understanding of this moment in trans TV history, and, best of all, developing a friendship with Daniel.

And now they’re back on The L Word. And Max is getting a happy ending. And it’s happening in an episode that has a nonbinary director and a nonbinary writer. This one correction, this one apology, this one episode is not everything. But it is something. It doesn’t erase the past — nor should the past be erased. Instead it adds a new layer.

I talked to Daniel about this new layer. I hope you enjoy reading our chats as much as I’ve enjoyed having them.

Drew: How have you felt since we did our interview? I’m wondering where you’re at with things like public perception and your sort of return to having a public image.

Daniel: I mean, I never meant to go anywhere.

Drew: (laughs) Right.

Daniel: It was a convergence of reasons that kept me out of the public eye. And it was significant to do that interview with you because it happened in such a caring way. There was a mutual respect that made it feel good and like it was meant to be happening. It took us a while to feel comfortable and figure out how to do it. I was careful and also you were careful. And that set a tone that everything else has been able to build on which has been amazing.

Drew: Has there been an increase in fan messages?

Daniel: I think there was an increase when there started to be an increase by me. What happened was because I’m Gen X I was unsure if I wanted to engage with social media at all. I only started my Instagram account when I went to Standing Rock in the service of hopefully putting stuff out. And after that I started to use social media a bit and I think that’s what initially put us in contact. I’ve grown to appreciate it as a place for people to contact me and to foster community with people who want to reach out. I like to be there in that way. It’s one of my side jobs. To help people along their journeys and just be there to hear their stories.

Drew: For any trans person with any sort of platform, you’re never just an actor or musician or whatever. You take on a role in the community that can become challenging to find boundaries and balance but it can also become the most meaningful part.

Daniel: Yeah and I think coming out of punk rock and riot grrrl-adjacent spaces, my association with social media will always be fan zines. So for me it’s always about having pen pals. I try to bring it back to we are community with each other as quickly as I can. I mean, it’s wild that I can represent this thing for people —the first time they saw themself reflected or the first time they saw themself on TV — but I try to be clear that this is what we all do for each other. It’s just a version of what we do in queer community.

Drew: How did the return to The L Word come about?

Daniel: Well, it’s a chain of events. I had a meeting with a friend of mine, Jenni Olson. She’s a queer film historian and filmmaker and ran Frameline.

Drew: I love Jenni! I interviewed Jenni!

Daniel: A genuinely amazing person. She came over to my best friend’s house to buy a silkscreen for a fundraiser thing and we saw each other and decided to meet for coffee. She had read the interview that you did with me and we just started talking about the misunderstandings that can happen regarding gender and generational stuff especially when it comes to media. As a historian I think for her it was very important to talk about this and check in with me. And through that process I realized that I really wanted to act again. So she introduced me to a few people, one of whom was Marja. We had a great general meeting but I didn’t think anything Max-related would come of it. It was just nice to meet and talk. We had a really generative hour long conversation. I also met with Thomas Page McBee who I’ve known about through mutual friends. We got to meet and talk and I just kind of put my desire out there. There wasn’t a space for me back in the day and I thought it was because I was doing something wrong and I wasn’t good enough to be part of it. Reflecting back it was actually more about transphobia and ignorance around nonbinary identities. But because of our interview and seeing that there’s more space in the industry now, I wanted to make it happen. So I just let them both know that.

Then Marja reached out to me this past springtime and said, “I have a dream to bring Max back and to see him thriving and happy. And I want it to be an equally healing experience for you. What would you need for us to make that happen?” She wanted to repair the harm of the past and to see Max happy. Marja loved that character and told that to me in our first meeting. Max represented not just transness but also a type of queerness and underground alternative culture for her and, I think, a lot of people.

I thought it through and then listed some basic things. No diva stuff but just things I’d need to feel comfortable coming back. I talked to Scott Turner Schofield who does this kind of advocacy. You know, for trans people my age you don’t really expect the mainstream to do anything. So it was kind of incredible to hear how there’s like on-set safety and people doing advocacy. You can have someone by your side to help you!

I also said I would like to talk to Showtime and the publicists to talk about what happened in the past that was harmful to me. Unbeknownst to them — there are new people working in those positions — but just to make sure it didn’t happen again. It felt important having played one of the first transmasc characters on TV to say what happened. I did it in a very caring and kind way and they were great. They listened. They apologized even though none of them were there. They heard what I was saying and assured me it was different now.

And then there were things like getting to see the script beforehand in case there needed to be adjustments. Because there was so much in the original series that was problematic that I had almost no input on even if I tried to have them change the harmful stuff. Everything I asked for this time was honored down to costuming. I mean, the whole scenario has just changed. The old crew was largely supportive, but we’re just in a different time culturally.

Drew: Speaking of crew, what was it like no longer being the only trans person on set? How different did that make the experience?

Daniel: It was great. It felt like I’d been waiting for this moment my whole life and I didn’t even know it was possible. I only worked two days so I didn’t get a chance to get to know the crew as a whole and I’m not sure how many trans people were working in general. But our director, Em Weinstein, is trans, the main writer, Nova Cypress Black, is trans, and then I got to work with Leo and Armand. Do you know Armand Field’s work?

Drew: Yes! They’re so good on Work in Progress and the new Queer as Folk.

Daniel: Yeah they’re great. Everything was just so different. Even down to the costuming, nowadays we don’t have to invent anything. There’s a precedent set. They’ve had years of experience working with transmasc actors and are like this is what we can do with the shirt, we can do this and that. Our old costume designer was amazing and always so supportive of me using whatever I wanted but we had to figure it out together.

Drew: Beyond any sort of missteps, there is just a difference between showing up on set and getting to just be an actor versus when you show up on set and you have to be an actor, a costumer, a set decorator, a consultant. I remember you talking about this in the original. And it often wasn’t from a place of maliciousness — they just didn’t know someone like Max so it fell on you to do all these other roles.

Daniel: Let me represent the underground queer. Let me teach the PR people. All of that. And it’s fine. We all do it as culture creators. You do it. I do it. That’s what we’re doing in this work. But it is kind of wild to come in and just be able to go to my trailer and work on the scenes while, at the same time, still being included in the larger creative process with other people who understood these things in their own way.

Leo and I were super into having this intergenerational queer connection. We wanted it to feel like this really affectionate, connecting moment where Max is encouraging and moved by Micah. This is how it is for queer people. We are each other’s family and sometimes pretty quickly you can have these bonds. That was really special. And also to show Max in this beautiful relationship with their partner which we didn’t see a lot of it in the past. I was very happy with the casting of Armand Fields and the way it felt with us all on set with Em. Everyone was so committed to this moment. At one point, Armand said, “Welcome back to your franchise” as if it’s Marvel or something. And I realized so much of what I experienced in the past was trying to prove I was a part of something because they always tried to make it very clear that I wasn’t really a cast member because I wasn’t a woman.

But these people — Em, Nova, Armand, Jillian, Leo — they all just made it really clear that they were happy I was back. It was a dream. I mean, I cried several times. And working in that environment with Nova and Em and these actors, it was the most fun day acting I’ve had since I was doing improv when I was young. Because we got to be innovative and try different things and people were supporting each other. There was no competition. It was exactly what you’d want queer and trans filmmaking to be. And I have to point out that of the five people I’m naming, four of them are BIPOC and that’s significant. They’re all from different backgrounds and I don’t want to generalize but for me that didn’t go unnoticed. And they’re all just uniquely amazing people. They were kind and encouraging. Armand was so affectionate. It felt like a special moment for all of us and for this character who they all seemed to love.

Drew: What was it like being Max again?

Daniel: It was fun! For me it’s like a spiritual thing. Because he’s a side of me. I put myself into him and fought really hard for the good things that were included. And I just think he’s a nice guy and I love to see him happy with a cute kid.

Drew: I mean, you know how I feel. I think people so often remember the missteps — to be generous — that happen toward the end and I really am such a firm defender of those early episodes with you as Max. And I do think L Word viewers got a chance to see Max, the person, before the writing and ignorance took the character places that were stereotypical. I think that’s why the character and your performance as him has the legacy that it does. Because there was so much to hold onto that felt positive and real and human.

Daniel: Even the style of some of the first ones because a lot of the people were filmmakers. Like the road trip with Jenny captured a lot of my trans experiences. Dealing with stuff on the road, bathroom stuff. I mean, I still deal with bathroom stuff. Just the other day I had people screaming at me in the bathroom — nothing has changed. But the dreamy element, two people on the road, the promise of going off to the city. It’s also class stuff along with queer and trans experiences.

Drew: There’s a moment in this episode when Shane apologizes to Max and it feels like an apology from the show itself. Had you previously received apologies from anyone who was a part of the original show along the lines of this fictional apology?

Daniel: I did take that moment as a meta way for the show to apologize to me as an actor and for Shane to apologize on behalf of the original characters to Max. I also think it’s meant to serve her character since she’s on her own journey of growth. But to answer your question, I received an apology from the Showtime PR people — even though they weren’t there back then. And I received apologies from a couple of the actors.

Drew: So this moment was a reckoning that hadn’t happened that often before in real life. Is it fair to say that?

Daniel: Yeah. For me, as someone who believes in the healing power of art — which sounds very corny—

Drew: No, I love it. Be corny.

Daniel: We will take that apology to mean everything because it’s not about me, it’s not about Max, it’s about our community and the system at large that makes harmful things happen whether people know it or not.

Drew: I’m really fascinated by the way that the original series starts with Bette and Tina having a baby. It feels like this moment of assimilation. The first show about lesbians is on TV and here is our central couple and they’re having a baby. They’re being domestic. They’re fitting into this normative lifestyle. And then by the end of the show when Max is having a baby, it’s not shown that way — it’s a circus freak show.

But now all these years later we get this storyline — for better or worse — of domesticity. And I’m really interested in the way in which it suggests that now it’s trans people’s turn to fit into this version of assimilation. On the one hand you can read it as these basic sort of stepping stones of representation — the ways in which society wants marginalized people to conform — but on the other hand it’s not like Max settled down with a cis woman and is modeling a heteronormative life for Micah. Max is in a t4t relationship where one of their kids is biologically from Max, two are biologically from his partner, and the third they’re fostering.

I don’t know if you have any thoughts on this. But I was watching it and just felt like what an interesting cross section of queer media that shows how things are cyclical and shows how you can chip away within the details to be a little more representative, a little more inclusive, a little more radical even.

Daniel: My wish was for Max’s present to reflect more of a life like mine. I don’t hang out with mostly cis people, I don’t hang out with mostly white people. Diverse is such a weird word but my community is mixed and diverse in all sorts of ways. That’s my queer community. So I wanted to reflect that kind of queerness and to show a mixed family background as someone who was raised by gay men as well as my mom and different stepdads. Not that Max is me but I wanted that. So I did request that Max’s partner be on the trans/nonbinary spectrum. But this was created collectively and I want to give all the credit to the writers. Those requests might have already been planned. It was just important to me that Max and his partner better reflect my own queer community.

Drew: It’s really beautiful that some of the subtext you gave to Max in the original series— Well, it wasn’t subtext, because a punk poster in the background is text. But let’s call it soft text. The soft text you brought to Max in the original feels really validated and fulfilled and made more explicit in this window into his life. That feels really special.

Daniel: These gestures toward a certain way of moving through the world, a certain politic. I brought an Audre Lorde poster from home. I did the same thing bringing posters.

Drew: (laugh) You’re like, I know I don’t have to anymore but I still want to be involved in the set decorating!

Daniel: (laugh) We have this gorgeous Audre Lorde print that my friend made. And it frames the beginning of the scene. I like having these gestures. And it’s especially meaningful to fill out the world in this way when you’re already working with the text of Nova Cypress Black, a Black trans writer. I think of writers in the best scenario as holding space for what is possible.

For me, this is the most exciting part of the whole thing. Because again on that set the way the actors worked together with the crew holding that space, it wasn’t competitive. It was all about mutual support and collaboration.

Drew: No more lobsters pushing each other down as they try to get out of the pot.

Daniel: Exactly! It was what I always wanted it to be like. It didn’t have to be scary. We could just do our best and help each other.

Chase Joynt on “Framing Agnes,” Collaboration, and Finding New Ways to Tell Trans Stories

When I saw the short film Framing Agnes at Outfest in 2019, my goals for the industry were simpler. I wanted more trans people on-screen and more trans people behind the camera. I cared about the how but not nearly as much as the what.

That has changed. I am exhausted by our visibility. I still want to see trans people on-screen — and even more so behind the camera — but not without thought, not without care, not without the resources to deal with the backlash.

It’s fitting then that one of the year’s best movies would not only be about trans lives and trans histories, but question the various forms of visibility trans people have experienced over the past seventy years. From short to feature, Framing Agnes has called into question its own premise.

Framing Agnes joins director Chase Joynt’s ever-growing body of work that upends conventional trans documentary filmmaking. From his short I’m Yours in 2012 (watch here!) that comments on the ways trans people are asked to perform our life stories to No Ordinary Man, last year’s unconventional Billy Tipton doc, Joynt’s approach prioritizes formalism and collaboration. The how is not only important to Joynt — it becomes included in the work itself.

It was such a pleasure to talk to Joynt about his influences, his process, and the responsibility of trans storytelling.

Chase: Drew, where are you in the world?

Drew: I’m in Toronto!

Chase: Always??

Drew: No. But about half the time because my girlfriend lives here. I’d never been to any part of Canada before two summers ago and now I kind of live here?

Chase: You know I’m born and raised near Toronto, right?

Drew: I actually want to start with that because I feel like your work has such a specific voice and set of interests and I do just want to know more about your background.

Chase: Yeah, sure. And it’s actually a very Toronto answer. I can skip the like, “When I was a child I felt this way…” details.

Drew: (laughs)

Chase: And instead say that I learned to make movies on account of being mentored by people like John Greyson, people who were making work throughout the AIDS crisis in the 80s and 90s in Toronto. I really feel indebted to a kind of activist impulse and aesthetic that says we have to make movies with what we’ve got, with the people we love and care about most, in the most urgent way possible, for immediate circulation. If we can up our production value then great but ultimately our goals are bigger than that. And I really do cite my early foundations in Toronto as the source of those ideas.

Drew: Do you also have any sort of theatre background? Because there’s a real attention in your work to actors and rehearsal.

Chase: (laughs) Yeah, you have clocked me correctly. I went to theatre school at UCLA.

When I arrived at UCLA I was in a room of 50 students and everyone was introducing themselves and someone in the room — who will remain nameless for the purpose of this interview — stood up and said, “Hello, my name is … and I want to be a star.” And I thought, oh no, where am I? And so I really took a turn away from the more industrial training at UCLA and instead found activist communities in LA. But I’ve sort of found a way back to that industrial impulse in recent years.

Drew: It feels like you’ve found an effective combination of those two practices.

Chase: The other thing I’ll say about theatre is that it’s all about rehearse rehearse rehearse and then when you get on stage you try to let that rehearsal go and be present on-stage, be in the moment, react and respond and improvise and be spontaneous. I think about that as it relates to documentary directing. There’s a kind of rigorous rehearsal to prep that you then try to let go of when you are “on-stage” and in circulation with your participants so you can break open new pathways for storytelling that are impossible to pre-plan.

Drew: For Framing Agnes, was there a rehearsal process before filming or is that all on-screen?

Chase: All of our actor collaborators had access to transcript selects that were loosely organized around the themes you see emerge in the film. How can we talk about love and romance across a variety of case studies? Or how can we talk about work? But what you witness on-screen is actually what’s happening in real time. So we’re workshopping, we’re stopping, we’re starting, sometimes we’re feeding lines back to each other because they’re not working or don’t feel good, and all of that is pretty organic to the set up.

Drew: How did you first discover the archive and how did the short come about?

Chase: We first discovered the case files in 2017 and the short premiered in 2019. We made the short with a little bit of grant money and a lot of credit card debt and many favors from friends. If you look at the short now you’ll recognize that we’re all wearing our own clothes and we’re eating granola bars and juice boxes. We shot the whole thing in one room and stapled curtains on a white wall to make it appear like a black box. I mean, it’s totally DIY and kind of awesome in that regard but when you look back it’s clear there were some experiments.

Drew: And then what was its journey into a feature?

Chase: We needed more money, to be perfectly frank. And so we started applying for more grants and received the Telefilm Talent to Watch grant which was enough production funding to pivot meaningfully toward the feature. And then we added our two extraordinary collaborators Jen and Stephen. We were in conversation with them about the short as well and it was scheduling and a variety of other things that didn’t work out. But in some ways I’m grateful because we were able to test drive some of the method in the short that we were then able to tweak and further refine when we approached the larger cohort in the feature.

Drew: So you knew Kristen Schilt (co-director of the short, researcher on the feature) before making the film? Can you go into more detail about discovering the archive?

Chase: If we had a lot longer I would really elaborate this story just for the humor, but Kristen was a TA at UCLA in a class where I was an undergraduate. She emerged in the room as this very goth, hair half dyed black, half dyed platinum blonde, beesnest style, and I was like a corduroy pant-wearing butch dyke. We looked at each other from across the room of blondes wearing Juicy sweatpants and knew we needed each other.

Drew: (laughs)

Chase: Cut to a couple of years later, I received a fellowship to work with Kristen at the University of Chicago where she is a professor of sociology. The fellowship charged an artist and an academic to work together collaboratively around a set of shared issues. And so we taught a class and one of the things we explored with our students was the case study of Agnes. We used it as a way to think about how different disciplines can attach to the same source material for very different sociopolitical motivations or research conclusions. And since we’re geeks we managed to find our way into the private archival holdings of Garfinkel and continue to explore our obsessions from there until we arrived at the transcripts and unlocked the whole project.

Drew: How did Morgan M Page and Jules Gill-Peterson get involved?

Chase: I’m a longtime fan of Morgan M Page. We identify as ships in the night in the Toronto up-and-coming queer and trans scene. I approached Morgan about collaboration precisely because of her extraordinary work in One from the Faults and broader trans activisms. I was so thrilled to be able to collaborate with her in that way.

And I knew Jules through her work and as an expert of this particular moment in time — the construction of the gender clinics in the US, the specifics of the kinds of research being done, and, of course, her writing on trans kids. We shot the majority of the film before the pandemic and had to take a break as all productions did. And in that break Jules and I started zooming.

I was really troubling over what the point of the film was at this point. Why now? Why continue to make this project? What’s at stake? For whom? It was through conversations with Jules that she emerged as the interlocutor that she is and I asked if she wanted to come onto the project more formally and more specifically.

We shot with Jules in the pandemic and finished the film on account of her extraordinary skill of interpretation. One of the things that doesn’t necessarily read on camera but is true to our method is that the night before we shot with Jules in LA, we screened sections of the edit in progress. Here’s what this section looks like when we’re thinking about the following thing. And then we had a core team meeting about the film and its on-going construction. So what’s happening on-screen in our project is Jules critiquing the film we’re making from within the film. And it’s only because her arrival to the project was delayed that she’s having something to actually react to and feed back to which then becomes the fabric of the project as a whole.

Drew: That’s so interesting. I do feel like your work in general is very aware of both the benefits and the limits of visibility. Even from the short to the feature, do you feel like your goals for our communities and for trans art shifted because of increased visibility?

Chase: Absolutely. And I can speak to your question concretely because you’ve seen the work. If you were to compare the short to the feature you would immediately recognize that we’re still trafficking in personal narrative as the way in which trans people are arguing for their dignity and their rights. “I was born in this place,” “I had these feelings,” “My feelings changed,” etc. We’re all familiar with the trans life narrative. And what I think emerges in the feature is a concrete refusal and resistance to play by those rules.

One of the ways it becomes visible is in my conversation with Angelica when she says, I’m tired of telling certain kinds of stories and I don’t want to do it. I want to control the ways in which my narrative is used regardless of what your project might be claiming to be about. I love that refusal. Refusal is an ongoing theme in the feature in a way that it is not in the short. And I think that refusal is precisely on account of your question — people’s exhaustion around a certain kind of visibility, the overuse of personal narrative, and the ways in which certain kinds of narratives are reproduced at the expense of so many other ways we could be talking about trans life.

Drew: Maybe the film itself is an answer to this but how do you as a trans artist… I guess I’ll just make it personal and say that while I feel like we’ve reached a sort of peak of visibility, I still have stories I want to tell, stories that haven’t been told, art that I want to make. And it’s frustrating to me that all of that is inherently going to be added to the visibility as opposed to just being my story or expression. And, of course, there are benefits to that as well, but I was wondering if you can speak to how you’re grappling with that moving forward in your work.

Chase: It’s an ongoing battle to be frank and succinct. But I think one of the things that Jules offers us at the end of the feature is this challenge of thinking beyond visibility. What happens when we think about invisibility or opacity as holding an incredible amount of political power? It’s still being said and baked into a project that is deeply interested in and invested in a kind of trans visibility, a kind of public reckoning with the ways transness emerges in culture. But that to me is the answer to your question — living in the tension, of the collision of those two things. How can we be at once talking about the limits and the dangers and the violences of a kind of return to visibility while making visible other forms of knowing?

This is for me as a formalist where I deeply start to rely on the role of the frame as one of the ways to organize our attention and to organize my own anxiety as a maker. If we’re thinking of the frame of the talk show or the frame of the documentary interview or the frame of the medical diagnostic exam, what can we learn about transness by actually deprioritizing the trans subject and instead thinking about everything else that is happening in that scene? Whether it’s the Mike Wallace or the Garfinkel or the me, what are the lights and stage that afford us the kinds of visibilities that we’re talking about?

Drew: When it came to the casting process, both for the short and the feature, was it just about picking great actors you wanted to work with? I think something for me that’s so effective is you have these people who — at least within the community — are these sort of icons. It feels like you’re playing with a tension there. Did that come about naturally or was it conscious?

Chase: It’s incredibly strategic. We open the feature thinking about the legacy of someone like Christine Jorgensen and the role celebrity and iconicity play in how we come to remember certain kinds of trans histories and subjects. And so it felt really important to me as a maker to be thinking with folks who already imagine themselves as being oriented toward a kind of public. I like the sort of meta geekiness that you can google everyone in our film and realize they’re each a portal to trans cultural production in very particular ways. They’ve each imagined their lives, their creativity, their art practices, as a way in which to intervene upon or think about trans life. We don’t need to tell you every single beat of that in the film but I like that it exists because I also think that it informs how people are approaching questions of performance, of truth, of visibility.

It’s also a deeply baked in acknowledgement of the limits and violence in documentary as a form. I’m not interested in trafficking in vulnerability for vulnerability’s sake. We’re asking a different set of questions. And I wanted to be sure that as we ask people to walk toward these subjects based on the sparks and resonances between their lives that everyone had already thought about what it means to be packaged as a trans subject and be able and willing to think about what’s at stake.

Drew: Was that part of the decision to not cast an actual teen to play Jimmy?

Chase: Yes. Precisely. And also because what a gift to be able to talk to Stephen Ira, someone who went through the very same clinic — albeit generations later — with those who were trained by the very researchers who we’re interrogating and thinking with. I mean, it was shocking and overwhelming and so emotional to be able to sit with him in that space. And he was a teen when he was there and that to me was all we needed.

Drew: Yeah, I mean, I’ve written a couple features about trans teens and I’ve thought a lot about the responsibility I’d have working with trans teen actors were I to make them. I’ve always been a pretty firm believer that teens should be trusted as people, but—

Chase: And they know who they are.

Drew: Yes! But that said the kind of visibility that is granted to a teenager who is put on-screen in a movie — even a movie that’s opening at the Film Forum — has an impact. And I think any filmmaker needs to be conscious of that and as protective as possible.

Chase: Absolutely. I know this is a grand statement — so recognize I understand that as I’m saying it to you — but I really invest in this kind of cohort doc as a way in which to protect and take care of each other. It’s a way to show up differently in the face of a culture that desires to consume and repackage our lives for various sociopolitical agendas that are actually designed to exclude us and/or limit our ability to survive and thrive. And when we’re reckoning with the logics of visibility I just could not imagine putting a trans teen in the center of the frame in this particular moment.

Drew: Staying on the topic of visibility, have Framing Agnes and No Ordinary Man increased your own visibility? Both among cis people and trans people and if so what has that experience been like?

Chase: No one has ever asked me that… You know, I think the visibilities that I’m most interested in are the ways in which people recognize the potential of hybrid form. So what happens when we run documentary alongside narrative cinemamaking techniques? What happens in that space? What happens in that friction? And if there’s any way I hope the visibility of these kinds of projects endures, it’s encouraging more risks in the non-fiction space by borrowing from beauty and aesthetics and narrative drama and all the other tools that are often stripped from more rigorous or gritty sociopolitical portrait pieces.

I think that transness emerges in the projects you’ve listed as a kind of method where we’re thinking across gender, we’re thinking across genre, we’re thinking across in a variety of different ways. I think we’re in a moment where we’re all inundated by a streaming culture where nonfiction work is routinized. We understand what it is before we even click on it. There are a few exceptions to the rule and wouldn’t it be glorious if we were able to really intervene upon the genre? Because I think intervening upon the genre creates a lot more space for minoritized subjects.

Drew: Yeah… You don’t have to answer, but I am going to push a bit.

Chase: (laughs)

Drew: I’m interested in all that. Don’t get me wrong. But I’m also interested in the ways in which— Look, the number of feature films getting any sort of theatrical release this year directed by trans people are minimal. And you’ll have one of them. I’m curious what that experience is like. I’d imagine there’s a lot of pressure that isn’t fair.

Because I actually am more interested in the things you’re talking about in terms of form. It’s why I respond so deeply to your work — I want trans art that is formally interesting. But I do think it’s worth talking about the experience of being a trans filmmaker in this moment in time. If for no other reason than to discuss that pressure and reduce it or, at least, contextualize it.

Chase: Yeah, it’s… (laughs) You know, I’ll be totally honest with you, if we were not being recorded, I think we would have a really different conversation.

Drew: (laughs) For sure.

Chase: But I’ll say that it’s a lot of pressure and it’s a lot of pressure differently from cis audiences and from trans audiences. I think that when we’re in a market where there’s only ever one trans film or a small handful of trans films, the pressure for that film to do many things for many people increases.

It also pressurizes the people in the film and around the film to become speaking subjects for the current moment. And so when we’re experiencing the extraordinary backlash against trans rights or against trans kids all of a sudden everyone in the film becomes a kind of speaking subject. Of course, Jules is ripe and ready, but there are different ways in which it pressurizes people beyond the means of their original participation. And I feel really protective and anxious about that cultural climate and I think it works against nuance to reduce everyone down to a kind of activist speaking subject especially if they don’t want to be such. The film should exist as a text outside of its people and the people should exist as texts in circulation outside of the project and I think you’re identifying something where everything becomes collapsed and pressurized.

One of the ways in which I manage it — which perhaps is very clear and very obvious by the way in which I work — is that I’m so interested in and inspired by the cohort approach to filmmaking, to storytelling, and to trans worldmaking. This interview is an exception to the rule. Very rarely am I alone with the film. I am always at every turn trying to be with other people precisely because I don’t imagine myself to be the person with all of the answers. I don’t imagine the film to have a static beginning, middle, and end that I can succinctly summarize. I hope that it is always something that is transforming and being reinterpreted on account of its context or its audience.

One of the ways in which we try to reckon with that in the film is to break frame and to have Jules walk away from us in the end. We’re not able to neatly summarize and conclude which might be frustrating for some people who desire a kind of emotional attachment or completion or catharsis from film. But I think we’re trying to say that now is not the time. We can’t meaningfully produce that because we can’t meaningfully produce it in the world that we live. And so how can we be somewhere else together in the space of the film?

Drew: I love that. Thank you for that answer.

Chase: Thanks for challenging me. (laughs)

Drew: The last thing I want to ask about is a brief moment with Barbara. I think she is such a fascinating figure. Like what you’re talking about in regard to a cohort, the trans histories that I’m most drawn to are ones where people were in community. Obviously not everyone had that as a possibility but I do love these little pockets where all these trans people were together and, you know, if not making art together, making life as art together.

Chase: Yes.

Drew: Anyway, she mentions something about a Hollywood starlet?? I mean, it’s very appropriate for the film that on the one hand I’m like, well that’s not my business, and on the other hand I’m like, wait tell me more! Is there any more context? Like is that suggesting there was someone who was a famous actress who was stealth?

Chase: That’s how I interpret it. The only person in the world who might have a better answer than that is Morgan M Page. But that’s how I interpret it.

I love not knowing who she’s talking about. What an extraordinary middle finger to the whole apparatus! And I include myself in that.

Queering the Canon: Where Are All The Trans Rom-Coms?

The two genres I enjoy working in most are horror and romcoms. They are polar extremes — showcasing our greatest fears and our greatest desires. And yet trans people have been largely absent from both — except as one-note jokes and villains.

That’s why it was such a joy to moderate this panel as part of Newfest and BAM’s Queering the Romcom entitled “Where Are All the Trans Romcoms?” It’s time trans people get to showcase our desires, in all their variety, in all their complexity, in all their possibility.

Rhys Ernst, Rain Valdez, and Eva Reign join me as we discuss the trans romcoms that do exist, what we’ve sought out in the absence of more, and what this lack says about society’s views of trans people.

Here is a Letterboxd list of all the films discussed in the chat.

Watch here. Transcript below.

Nick McCarthy: Greetings. My name is Nick McCarthy and I’m the director of programming here at NewFest, New York’s leading LGBTQ+ film and media organization and one of the curators of Queering the Canon: Rom-Coms, running April 28th through May 2nd, both virtually nationwide, and at BAM in Brooklyn. This series is presented by NewFest and BAM. It’s my pleasure to welcome you to this virtual conversation, titled Where Are All the Trans Rom-Coms? with an esteemed panel of artists and filmmakers. We’d also like to thank our friends at Autostraddle for helping make this conversation possible.

Now, it’s my pleasure to introduce the collaborator and the moderator for this conversation, a writer, critic, filmmaker, and co-host of the podcast Wait, Is This a Date?, Drew Gregory.

Drew Gregory: Hi, everyone. Thanks so much for joining us. I’m so excited about this panel and our panelists. I’m just going to jump right in and introduce them. First, we have Rhys Ernst. He is an Emmy-nominated artist and filmmaker, the director of Adam, which premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival and screened at NewFest, in addition to winning awards at Outfest, Oslo Fusion, the Mezipatra Film Festival, and was nominated for a 2020 GLAAD award. Rhys?

Rhys Ernst: Hello, thanks for having me.

Drew: Next… Sorry. Are we supposed to see… Okay, great. Can you-

Rhys: Hi, I wasn’t sure if I was on camera. Hi. Thanks for having me. Good to be here.

Drew: Thanks for being here. Next, we have Eva Reign. She’s an artist, actress and activist. She’s the star of Billy Porter’s upcoming directorial debut, which is a high school-set romantic comedy that’s set to be released later this year.

Eva: Hey.

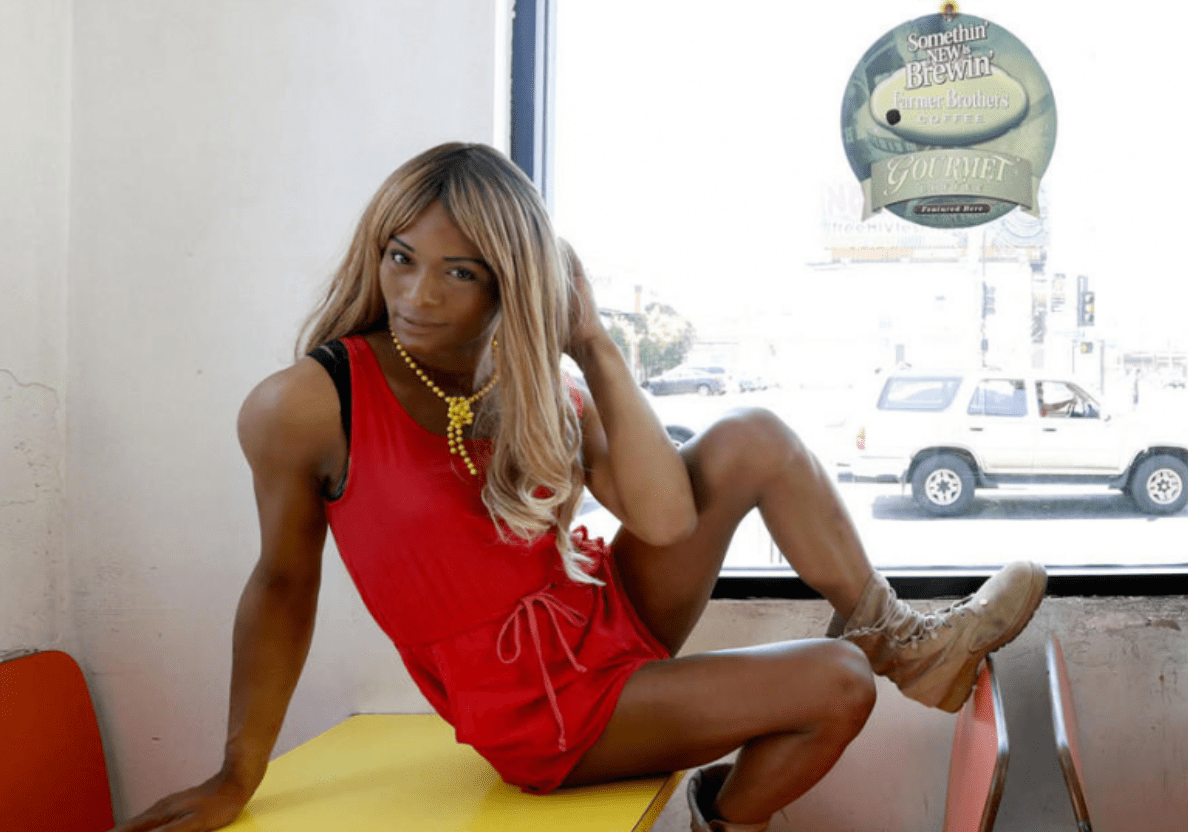

Drew: Hi, Eva. And finally, we have Rain Valdez. She is an Emmy-nominated actress and filmmaker. She’s the writer and star of the 2019 rom-com web series Razor Tongue, and is currently in development on her directorial debut, a trans-led rom-com titled Relive: A Tale of an American Island Cheerleader.

Rain: Hi.

Drew: Hi, Rain. Thank you all so much for joining me. I’m really excited about this conversation because I love rom-coms and I love trans media and I love talking about how we need to improve both of those things. I want to start off by… Okay. I put together a list of trans rom-coms that do exist. Maybe we can disagree about whether they should be considered rom-coms or trans, maybe I forgot things, but I just want to start off by listing them off. So, first, Adam, then Alice Júnior, Better Than Chocolate, Boy Meets Girl, Girl Stroke Boy, Holy Trinity, and Some Like It Hot. Have we seen these? Do we like these? I’ve seen and like Adam, I’ll say that right here, but how do we feel about this list? And did I forget anything?

Rhys: I would add Victor/Victoria.

Drew: Ooh.

Rhys: I don’t know if people have seen that one.

Rain: Yeah, there’s some bad ones from the ’80s and ’90s that I don’t want to list, but I think we talked a little bit about them on Disclosure. But that’s a good list.

Rhys: Yeah.

Eva: I haven’t seen most of the things on that list. I’ve seen Adam. I’ve seen Boy… yeah, I’ve seen Boy Meets Girl. Aside from that, everything was kind of new to me, but, yeah.

Drew: Yeah. I don’t know. I just watched Girl Stroke Boy, have any of you seen that?

Eva: No.

Drew: It’s a British movie from the ’70s that is like a riff, I guess, on Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, but I think is actually a little bit sharper. But as that list shows, there’s not a ton out there. So I’m curious what each of you have turned to in the absence of explicitly trans rom-coms. We can start with Rain.

Rain: Hmm. Well, first of all, I did see Adam. I loved it. And I saw Boy Meets Girl. I’ve seen that. It’s been a few years. I didn’t necessarily think that was a rom-com, but I saw it kind of gearing towards that genre, that people refer to it as a rom-com and I just kind of agreed. I’m like, “Yeah. Yeah.” But it’s more like an indie vibe. But I appreciate it for what it was.

Rain: There isn’t very, to be honest with you, in terms of trans-specific rom-coms, there isn’t anything that I gravitate to, but there are a lot of old classics that I can see from a trans lens because of… The thing about rom-coms is there’s always this high-concept conceit. There’s always this ruse or a lie or something. And so, for me, I can easily find myself relating to some of the rom-coms that are traditionally done by white creators and has Julia Roberts in it or Sandra Bullock. Because of that high-concept conceit, I can level up my imagination and kind of see myself in them.

But in terms of an actual go-to, I don’t really have any, sadly.

Drew: You don’t have a favorite, even among not trans rom-coms, but of those old Hollywood or even newer Hollywood rom-coms, do you have a favorite rom-com in general?

Rain: I do, yes. Oh, so that’s what you mean by that question?

Drew: What have you latched onto in the absence of trans rom-coms?

Rain: Well, I always thought Pretty Woman was very trans allegorical or whatever, because any trans woman who’ve seen that movie can relate to Vivian Ward or Kit De Luca. Maybe because they’re sex workers, which is a narrative that we haven’t really quite seen before in terms of that genre, and having it also be aspirational. And because they weren’t specifically cis or trans or anything like, in my imagination, I was just like, “Oh, Julia Roberts is playing a trans woman.” So I can enjoy it from that perspective because of the whole conceit of they’re doing this thing for a week, but then also they don’t want anybody in the Beverly Hills circle to find out what she really is. I found myself being able to relate to that, and then having a little bit of shame when people do start to out to find out. She started to… Well, she got angry about it and she almost left the whole thing because of that sense of betrayal of him saying something to his lawyer friend about what she is.

For me, it’s always in these high-concept rom-coms or movies that is somewhat rooted in identity that has a little bit of a shame to it, but then ends up being aspirational. The Little Mermaid, for example, I don’t know if that’s a rom-coms necessarily, but it kind of is, even though it’s Disney and it’s animation and it’s… To me, Ariel is the ultimate trans girl, because she identified… Well, she was born a mermaid, but identified as a human and did everything she could to become that person, and ended up having a better life because of it, or at least a happy ending. So things like that.

Even with, I think one of my favorite Sandra Bullock ones… Well, actually there’s two. It’s While You Were Sleeping and The Proposal, which are very similar to each other, because, again, there’s this high-concept conceit, there’s this ruse, there’s this lie. As the stakes get higher, there’s more of this pressure of making sure that no one finds out that she’s been lying this whole time. But then, as she falls in love with the family and the family falls in love with her, there’s this duty to tell them the truth about who she is or how she got there, in hopes of letting them know that, “I need to tell the truth because I love you all too much.”

Because of those ideas and concepts that are very similar… Like, The Proposal is very similar to While You Were Sleeping, it’s just a different ruse, it’s just a different lie. But I think a lot of people can relate to that or at least find that connection. At least I have been able to, which is kind of why I think I love rom-coms so much, because…

Drew: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

Rain: Yeah.

Drew: Eva, what about you? Do you have a favorite?

Eva: Well, The Little Mermaid is definitely one of my favorite films. I literally have a mermaid tattoo on my leg just because… yeah, I think just the whole notion of starting out as one thing and then turning into another and then having issues with the bottom half. Just all of those sorts of things, it’s like super, super trans. So yeah, The Little Mermaid is something I’ve watched a dozen times. Fairy tales in general, I think there’s a lot for trans folks to pull on, just this whole notion of magic, changing, being something different than what people say that you are, and breaking the rules to do that. I think those are the sorts of things I’ve definitely latched onto.

Growing up, I couldn’t really find myself in film or anywhere on television or even, really, in books. So I just tried finding as many queer movies as possible. Most of it I found on Tumblr, not legally, but it was there. I mean, I was always just trying to find some sense of self and anything queer. A lot of just super indie movies that don’t get a ton of press, but yeah, those are the sorts of things I’ve latched onto. I think also comic books and also even just other cis-centric narratives, I try to find something there.

I can’t really think of anything at the moment, but yeah, any love story, I’m kind of obsessed with because I’m just sappy that way. A lot of movies from the ’90, 2000 to 2004 stuff, with Sanaa Lathan, and just a lot of movies that were, I guess, thought of as Black Hollywood, those are the things that I latched onto because that’s something that I can see myself in. Maybe gender-wise, it’s not super specific, but yeah, those are the sorts of things that I’ve always latched onto, really just looking at any sort of media. I guess anything grounded in something real, but that still has that sense of flair to it is what I would look to.

Drew: Rhys, you mentioned Victor/Victoria. Are there any others that even are less trans?

Rhys: Yeah. Well, I wanted to touch on the point that other people have mentioned about The Little Mermaid, because I thought that was a really interesting one to bring up. I wouldn’t have thought of it as romantic comedy, but it is, that does really work. However, the original, the Hans Christian Andersen story doesn’t have a happy ending, of course, and the mermaid… It’s actually quite sad.

For me it brings up something I was thinking about with this question, which is, Rain, you mentioned the problematic ’80s rom-coms that we can put to the side, but some of those to me, as a trans person, I think are both problematic and quite interesting, in particular some of the gender-swap ones, like-

Drew: Right, I want the titles. Let’s talk about them, even if we’re-

Rhys: Yeah. I feel like there could be a lot more said about some of these ’80s gender-swap movies that we grew up on, and what did they do to us as trans people, or how do we feel about them? Maybe that’s what you’re getting at here with this whole panel. But Just One of the Guys, Strawberries, there’s others. Those are the main two. Ladybugs was Jonathan Brandis joins an all-girl soccer team, so he dresses as a girl. Just One of the Guys is the reverse of that, where a girl cross dresses as a guy and then of course falls in love with the guy on the other side. In both of those cases, it’s kind of like The Little Mermaid. Well, they don’t die at the end, but they don’t get their love. Or actually that’s not true. They do… I guess I’m sort of misspeaking. They get the girl, get the guy, but they have to go back to the way they were before. It’s sort of a unhappy ending. It’s annoying for us as trans people, that was what we grew up on.

One that I came across more recently, that I think is really interesting, is called Something Special / Milly/Willy. Do you know about that one?

Drew: I do. I actually just watched it this week for this panel.

Rhys: I actually really like it. Jenni Olsen turned me onto it. Jenni, who’s a queer/trans historian and filmmaker, she owns prints of it. We did a talk after the film… Because it’s one of these gender-reversal rom-coms, mistaken-identity films from the ’80s, but it’s kind of weirdly… I don’t know what you think about it, Drew, but I think it’s almost weirdly… It’s just a touch ahead of its time. I mean, it still falls back where the main character de-transitions, but not exactly. The main character sort of ends up non-binary or something in [inaudible 00:16:29] way for an ’80s rom-com. I guess we could get into a whole conversation about that film in particular.

I think it’s interesting to look at particularly the ones that deal with gender directly, and how in the past what we see as queer and trans people, that justice was not served, in fact the wrong thing happened at the end in that these protagonists had to de-transition or didn’t get the girl or something like that. But how do we think about that and course-correct it? And also just think about how those affected us as young people, watching those films. Not just in all bad ways, but in complex ways.

Drew: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think what’s interesting about that movie is, at the end, when she de-transitions, her hair’s still short. Pamela Adlon plays the kid, and even still now she has such a tomboy aesthetic. So it’s not convincing at all. She’s in this dress and you’re like, “Okay. Give it another year and I think you’re going to be a boy again.”

Rhys: Asymmetrical haircut or something like that.

Drew: Yeah.

Rain: Yeah, I remember that one. Yeah. Pamela Adlon, short hair at the end with the dress, yes, I do remember that one. I’m glad you guys brought that up.

Rhys: It’s sort of a lost jewel, almost. I mean, it’s kind of a weird film, but it’s interesting. You can find it on YouTube. The whole film is on YouTube. You can watch.

Drew: I mean, it also goes to me including Some Like It Hot, which I think falls into this, I would say. From Shakespeare’s time of cross-dressing rom-coms that are not trans, and oftentimes the cross-dressing is played as a joke, I think, the worst of it is that way and feels really bad. It’s a lot of what I think of growing up with, like even just cross dressing in Monty Python and stuff like that. But Some Like It Hot, for me, whenever I revisit it, the joy that Jack Lemon has being a woman makes it feel so trans to me. I’m like, I don’t know if it’s supposed to be played as a joke, but it doesn’t feel like that’s the joke. But I don’t know how we feel. Are there ones in that sort of genre, whether it’s a Shakespeare play or a movie from the ’80s, that you really love, and are there ones that you still remember as being sort of traumatizing?

Rain: I mean, I do love that you got that perspective From Some It Hot, because I got the same perspective. It’s a movie that I enjoy watching. I had my my acting class, we did, over the pandemic, we did like a book club kind of thing where we’ll watch a movie and we’ll talk about it. That was one of the movies that we watched and we talked about over the pandemic. I do appreciate how they just carefully crafted it so that it didn’t feel jokey or like a costume. At the end, with that line on the boat, it was just so sweet and it was just so gratifying. It was just so different from all the other movies that I was watching, growing up, that at the end of that movie I didn’t feel bad about myself.

Drew: What about you, Eva?

Eva: I can’t think of anything from the ’80s, but I don’t know if you all have seen Billy Elliot, the movie about the boy who starts dancing. His best friend, Michael, would play with gender and dress. I watched that movie when I was 10 and I always thought that Michael would grow up to be a trans woman. In the last scene, when they’re 10, 15 years older, he isn’t. I don’t know, that’s just something I’ve always seen as… I don’t know. There’s just different moments where I saw someone assigned male at birth, who was super feminine and it was kind of hinted that they were struggling with gender one way or another, and then either they “manned up” at the end or they were just like a cis gay man in the end. That’s the only thing that really comes to mind.

But yeah, that’s something that I always talk with my friends about, about how Michael was actually meant to be trans. I’ve gone through Reddit threads and there’s other people who have the same thoughts, so, yeah.

Drew: I love that. I love how we find these works and a lot of us will find the same things within them. I mean, I know for me a lot of old Hollywood, like screwball romantic comedies really resonate in a sort of trans way, in this very, I don’t know, basic, maybe even stereotypical way. But as a kid, they were this version of this soft masculinity that like Carey Grant would have sometimes where he was sort of bumbling and sensitive. And then you’d have like Katherine Hepburn being this strong, powerful woman. At the time, I feel I was so drawn to Katherine Hepburn from a romantic sense, because that’s what I was told that I could do, and also because how could I not be, but also then would latch on to Carey Grant.

I think, as I got older, I realized that I was sort of splitting myself. I also feel this way about the before movies, like Before Sunrise and stuff, where I’m like, oh, as a kid, I was equally identifying with both of these characters. It was like my masculine side, which was sort of effeminate, and the feminine side having these conversations and falling in love. It’s interesting to see that oftentimes in romance genre is where we get a soft masculinity because they’re often targeted at cis women, and so you get to have men, or I don’t have to do quotes, I guess, they’re men, men who had some of the qualities that I was bullied for, but they’re lifted up as a romantic lead.

I want to pivot a little to talk about what we think that this absence… Because it’s great that we’re finding this and it’s great that I can watch Bringing Up Baby and be like, “Oh my god, this feels very trans to me,” but it’s not. We can also acknowledge that and be like, “What we deserve and what should exist does not exist.” So, I’m curious, we could talk about what we think this absence represents for society’s views of us, and what it means to be denied this wish-fulfillment love story.

Eva: Yeah. I was actually talking with one of my trans sisters yesterday. We were talking about how, when it comes to finding a partner, especially for cis people, trans folks are not something that really comes to mind. I think the way a lot of us are raised, and it doesn’t even matter class, culture, race, whatever, your partner says a lot about who you are. People have a lot of shame just buried within their own hearts, their own minds. The thought of being with a trans person, I think, is kind of overwhelming for a lot of folks, even those who are attracted to us in whatever way, whether it’s secretive or it is something that they are trying to be more open and public about.

I think a lot of folks… I think trans people, we kind of represent this notion of someone who defied all odds, who deviated from culture and from what the world wants us to be, and people just want their white picket fence, their spouse with the 2.5 kids, and with the dog or a cat. I think the fact that there aren’t a lot of trans rom-coms, or just even the idea of trans dating being this constant topic of debate, scrutiny, I think it says a lot about how people value us and how they don’t want to think of us in that way. I mean, they do, obviously. There’s debates about it on Fox News every other day. But people don’t want to think about us, especially in a positive way and a way of, “Oh, yeah, maybe my son one day will grow up and marry a trans woman. Maybe my daughter will marry a trans man,” or whatever. People…

Ooh. There went my light.

People, they want their perfect idea of whatever, and I think they see us as wrong, as deviant. When people go to see some happy, perfect movie about love, they don’t want to have all of the questions running through their mind that trans folks bring up. So I think it’s a really deep thing. Yeah.

Rain: I agree with everything that Eva is saying. I think it also says a lot about Hollywood and how much influence and power it has over the world, society and culture. Rom-coms to me is the most subversively political genre because it teaches us who gets to be loved and who doesn’t. It teaches us who is deserving of a certain kind of love and a certain kind of partnership. So if we’re constantly centering cis and white and heteronormative, then we’ve just been telling Hollywood or the industry, through this media, has just been influencing and telling the world that these very specific type of people are deserving and are worthy of being loved or being in a relationship or having a happy ending, and, basically, trans people don’t.

So, for me, it’s like that sort of… As a actress and a filmmaker, it’s like it’s been a thing that I’m constantly learning. It’s like, “Oh, it’s maybe not necessarily how we’re perceived or how the majority of the world feels about us, it’s just what we’ve been putting out there in terms of information and conditioning.” So it creates that fear that Eva was talking about, of how people don’t aspire to fall in love with trans people, or that when they do, they think it’s something to be ashamed of.

Rhys: Yeah. I would just add… I agree with everything that both Eva and Rain have said, but also that I just think it’s still a product of so few trans filmmakers being given access to create work. We just have such a bottleneck of… I mean, if we just think of… I was actually trying to think, “Well, outside of rom-coms or what could be construed as rom-com, how many trans comedies have there been made?” And then I’m like, “Well, what about trans genre films like mysteries?” You know what I mean? It’s just like there’s just not that much, period. I think it’s still just… Because I wouldn’t really… What I’m certainly not asking is for cis filmmakers to start telling trans rom-coms. I mean, I don’t know, I’m not saying they’re not allowed to ever if they do an amazing job, but it’s not really what is underneath the ask. It’s about access.

I think we still have this challenge, this catch-22 about recognizable actors and if actors haven’t been given the chance, and then how that’s so connected to financing. So there’s that whole thing, which is very old thinking, I think, and to evolve. It’s starting to evolve in some places. You’re starting to see more underrepresented types of people on streaming and in some films. But we just need to escalate this access, the financial means and material means to make more work. So, yeah.

Rain: Yeah. I definitely think the material is there now, well, with this group of people particularly, but also just with how many filmmakers and actors that are now working their way into the system and into Hollywood. But we just haven’t really found that direct line to financing that bridge of getting just people to really put their wholehearted belief that this is something that could actually work and that people actually want. Because I think we’re still stuck in this idea that, “Oh, well, we already have that one show where we already have that one actor, actress, so why do we need another one? Why are we listening to this pitch?” I think that that’s an archaic belief system as well.

It’s really hard for people to recondition that thinking and get past that, because there’s, I think, there’s an obsession, in a way, to trans people’s origin story, like the transition and the struggle and how that creates an explosive dynamic with their family or their work or whatever, but they can’t seem to fathom that there’s more story to tell beyond that. So we never really get stories about love or healing, or even starting from there and seeing what else is beyond that, because there just isn’t that belief that that’s even warranted.

Drew: Yeah. I’m also interested in the romances that are told in trans movies, specifically, in trans movies that are made by cis people, because that’s mostly what’s existed, at least in the mainstream. The fact that I can think of movies that are explicitly trans and have romantic storylines of sorts, but that I wouldn’t even suggest in a rom-com conversation, because it’s always filled with a lot of darkness. So I also feel that is connected to all of this, like the idea that cis people are very aware that either they or people are drawn to us, but then it’s this idea that it has to be done in a way that’s taboo, in a way that, I don’t know, involves death often, or at least some sort of trauma.

Rain: Yeah.

Rhys: Actually, Drew, can I ask you, because you’re such an expert, I would say, on queer and trans film history and film history in general, do you feel like there’s a parallel to what you just described, like the gay and lesbian films, and how close… you know what I mean, in terms of like 30 years ago with gay and lesbian films, or further back even? Because there was always, for example, the trope of the doomed lesbian romance where one of them dies. So you have some of these parallels with some of the trans romances you were talking about. Do you think that very close or…

Drew: I think it’s really close. I also think it goes to what you were saying about how the goal should be to have trans creators who are getting to tell a variety of stories, because I could see a world where we’re having these conversations, we’re fighting for change, then the changes that happen are done in a way that’s simple. And not to say that there aren’t a lot of really incredible cis queer rom-coms and romances now, because there are, but a lot of them are more independent, and even among films that are independent on a Sundance scale, a lot still tend to be very… They feel straight, but they just are gay. I don’t necessarily want a world where it’s like, “Oh, it’s cis, but we’re casting trans people.” I mean, that’d be great. I obviously would rather that than nothing. But I think all of us here could bring more nuance to what a trans rom-com could look like, in a way that I hope… I hope that’s the future.

But, yeah, I even think about, I don’t know, this other movie from the late ’90s, I think, like Different for Girls. That is probably the closest, I think, there is to… It stars that cis guy as the trans man, but it’s probably the closest-hitting basic rom-com beats. But then it has just brutal acts of transphobia and it’s so unpleasant. It’s as if like you were watching a Sandra Bullock rom-com and in the middle of it, she was brutally assaulted. It would be so jarring and it would not do well. But this idea that even in that version of a cis person being like, “Ooh, let’s take the rom-com beats and apply it to a trans person,” it’s going to be, “We still need that moment. We still need to show the pain.” I just think that there’s such a world in between ignoring the differences of being trans and in love in the world, and acknowledging them in this way that is simplistic and violent and painful.

But, yeah, I definitely think we’re at a place, like we are on a lot of categories, for trans people where cis/queer people were, both the ways that we’re attacked in media, whether directly or through fiction, I think we’re seeing very similar patterns, for sure.

Rhys, I want to ask you about Adam and about whether you were thinking about the rom-com genre when making that. Was that something that was… Do you think of the movie as a rom-com? Now it’s sort of fun because the actor who plays the cis-bisexual girl isn’t cis, and you can read that onto that performer, but were you thinking of it as a rom-com?

Rhys: You know, I actually wasn’t. Well, that’s not totally true. I wasn’t at first, but then, particularly towards the second half of working on it, and when I was really zeroing in on Adam’s relationship with his roommate, Ethan, who’s played by Leo Sheng, that relationship is what I gave the rom-com treatment to. But it was kind of like the secret rom-com of the movie, was the romance between them. Particularly in the edit, I was really working with the editor, like, “Let’s give Adam and Ethan the rom-com pass. We have to really do eye contact when they first meet.” Really we were looking those beats.

But no, I didn’t at first. Even for this conversation, I was like, “Oh, rom-coms, huh. Well, what rom-coms do I even like?” I wasn’t even sure if I liked rom-coms. I had to think about it for a second. I guess I don’t identify as a rom-com fanatic. But then, when I thought about it, a lot of movies I love are rom-coms. It’s a funny thing. I think there might even be some belittlement put on this category because it’s perceived as for femme… I think that there’s a misogynistic lens on how we talk about rom-coms sometimes. But I’m a lover of film in general, so I think we need trans takes on The First Wives Club or something like that and we also need trans takes on really challenging art-house whatever. You know what I mean? And everything in between.

But you all are raising really important points about not only how do viewers identify with perspective and an amorous gaze… Can we have an amorous gaze towards a trans person or as a trans character, one or the other or both? I mean, obviously the gaze is so important to the construction of film history, and it’s been the white cis male gaze for so long, straight, I can add qualifiers onto it. I think it just, in a way, it just takes something to break open. I was thinking about… I just saw the film Desert Hearts recently, which was a… I don’t know if it’s a rom-com. It’s kind of rom-com, right? It’s a romance.

Drew: Yeah. I don’t know if I’d call it a rom-com, but it’s definitely a romance and there’s definitely humor in it, so it’s like-

Rhys: Yeah.

Drew: Yeah.