Editor’s Notes: On Time Zones Week

I think about time zones a lot.

Because the majority of my most formative friendships began on tumblr, all of us flung across the globe, all of us online at strange hours just so we could catch each other.

Because I’ve shuffled between Eastern, Central, and Pacific throughout my 29 years of living in nine different cities.

Because every relationship I’ve ever been in has, for a significant stretch, been long distance.

Because of that summer I wasn’t sleeping and kept a mental catalog of which friends I could text when it was 2, 3, 4, 5 o’clock in the morning my time without worrying about it being a bad time for them.

Because my dad was overseas a lot when I was growing up and once lived in a place with a half-hour time zone, and no one ever believed me about it!!!!

Because someone in my pandemic game night group started saying “6/8/9 damn so fine” when confirming what time we would be meeting within our respective time zones.

Because I just started working full time here at Autostraddle, where the senior team is spread across two (and sometimes three, thanks to Laneia living in Arizona which likes to make up its own temporal rules) different time zones, so it seems like we’re all counting out hours on our fingers before agreeing to meeting times.

It really is that last one that led to me creating Time Zones Week tbh. Starting this job placed time zones front and center in my day-to-day brain in a way that hasn’t been the case since I lived in Chicago (I feel like living in Central time is just, like, endless time-math for some reason??? Like even worse than Pacific somehow???).

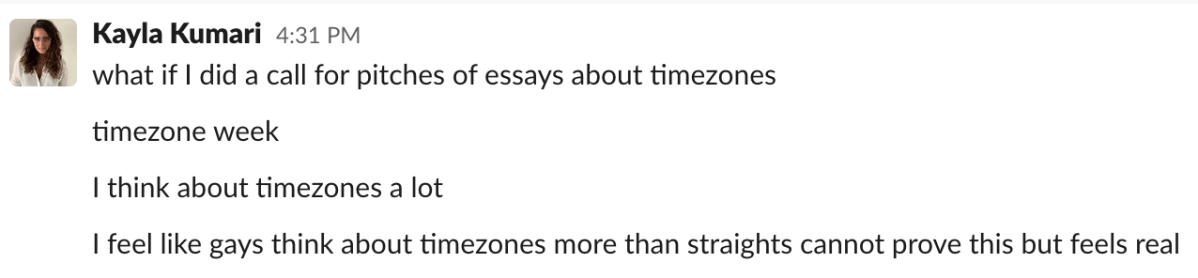

So I threw this out there to the rest of the senior team:

you will note that these messages were sent before I learned “time zones” is two words, not one

And then this:

Thankfully, people did have interesting things to say about time zones. I anticipated a lot of pitches about how Time Zones Suck. I was technically open to essays of that nature, bc yeah! Time zones do indeed suck! But ultimately, the six pieces I moved forward with (HAVE YOU READ THEM? GO READ THEM.) were more about bending time zones. They were about finding ways to transcend physical and emotional distance. They were even, sometimes, about time zones being Good. Like how time zones meant I almost always had people to text when I couldn’t sleep that summer, others found strange and surprising upsides of temporal dissonance.

I wasn’t ready for how much these pieces would teach me about time zones, a thing I thought I knew so well. Grief has its own time zone. Relationships are their own time zones. Kitchens have their own time zones. Time can be bent, and it can jump, and it can hurt, and it can heal.

When I met with artist and designer Vivienne Le, who did all of the outstanding illustrations for the series, they said they promised they wouldn’t draw any clocks. We laughed. We were on the same page: NO CLOCKS ALLOWED. (We also both admitted it was hard not to think of clocks when reading the pieces, be they literal or abstract.) Viv had another rule in mind: no straight lines. These illustrations would be curvy, swirly things unrestricted by the confines of straight lines, of time.

Vivienne nailed the vibe and scope of these essays, all distinct and yet bound by some unintentional overlaps, like the fact that they all more or less deal with a relationship between two people (in the case of Dani’s, I see that relationship being between two of her selves). As with the words on the page, the artwork time travels. It’s playful and a little haunting.

And WITH THAT, I will leave you with these VERY COOL behind-the-scenes process videos Vivienne surprised me with that provide a little glimpse into the magic behind Time Zone Week’s otherworldly art.

My Jackie: On Yellowjackets and a Missing Friend

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

We met when I was 16 and she was 17. We called each other bou, wife, love, babe, baby, sexy, (and somewhat inexplicably) George. We weren’t dating, but we might as well have been. I’ve been thinking about her more than usual lately, ever since I found myself obsessed with Showtime’s new show, Yellowjackets, like much of the gay internet. It was specifically the best-friendship between sparkling popular girl Jackie, and her quieter sidekick Shauna that got me. My Jackie, she disappeared midway through our twenties and in some ways I feel like I have been chasing her ghost ever since. Even though we weren’t lovers, whatever we felt for each other was a lot like being in love. If we were on TV, a fandom would have shipped us and scored a video montage to Lucy Dacus or girl in red. We traded more I love yous between us than I’ve exchanged with anyone else, past or present. I am 30 now, and my Jackie went missing when I was 25. I can’t tell you her name, so I’ll call her J.

Female friendship is fertile terrain for literature and film. The internet is littered with women eulogising their intense friendships, and meaning-making out of endings with poetry and metaphors like half-lives, myth-making and haunting to describe the feelings that linger long after you have run out of the right words to say to your friend. I get it.

Personally I would have liked us to be Abbi and Ilana from Broad City but less stoned and more ambitious. Or Maya and Anna from PEN15 because they’re writers, except we met in college and were both deeply mentally ill jk but no srsly. We could have been these pairs, maybe for a while we even were. But mostly, I see us in Shauna and Jackie from Yellowjackets, because Jackie is gone and Shauna is haunted by her irreversible failure at being a friend. Same.

For the most part, our friendship lived on the internet because IRL we lived on opposite sides of the world most of the year. J was studying English literature in sweaty, humid Calcutta where it was summer most of the year. I was studying molecular biology in a small university town in Canada, where it seemed to always be winter. We’d had a whirlwind courtship period of falling in friend-love in July when we were briefly in the same English program. Then, for myriad wrongheaded reasons, I transferred out to pursue a Bachelor’s of Science, and we were suddenly long-distance. Between 2009 to 2015, our friendship lived so completely online — across time zones over 600 emails and Gchats, Facebook posts and messages, Skype calls, blog posts on Blogspot.com (RIP) with allusions to each other — that it seems unreal that the internet has been scrubbed clean of her presence. No Facebook, no Instagram, no Twitter. She did it herself.

It’s been a confounding mystery to those of us who knew her: In this age of social media overexposure, how can someone have so completely disappeared? I have been writing this essay in my mind for years. Until I watched Yellowjackets and saw Shauna haunted by Jackie, I did not have the right form for what I wanted to say. Now I think I know.

In Yellowjackets, Jackie and Shauna are high-school best friends and members of a soccer-team that has made it to nationals. Jackie, the team-captain, seems to be the archetype of a popular girl, while Shauna is more of a wallflower, journaling in the car as she waits for Jackie to be done hooking up so they can drive to school. When their plane heading to nationals crashes in the Ontario wilderness, Jackie slaps Shauna awake, and pulls her out of the burning wreckage. Eventually, Jackie discovers that Shauna has been sleeping with her boyfriend Jeff and is pregnant. This betrayal, combined with the waning importance of her popularity and a descent into Lord of the Flies-esque behaviour by the rest of the team leads her to lose all faith in life, love, and friendship. Her nihilism ultimately escalates to a fight with Shauna which leads Jackie to sleep outside, in self-exile. An overnight snowstorm leads to the climax of season 1: Shauna digs Jackie’s blue body out of the snow after she freezes to death.

My Jackie disappeared when I was 25 and she was 26. Last I heard, she was in the hills in the Northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. And then suddenly she was nowhere. I didn’t dig her out, because I don’t know if she’s still alive.

Let me tell you about her. She was a writer. J was extraordinarily, ruthlessly intelligent with an encyclopaedic knowledge of pop culture. She came first in class, did theatre, and was incredibly insecure. She was tall and dark-skinned, with big black eyes, and a button nose that belied her sharp tongue. She wore glasses and, later, wore her curly hair short.

J grew up with a mother who loathed her and made sure she knew it, as often as possible. Her father’s bipolar disorder was a secret so shameful to middle-class Bangalis that the family propagated the rumour that it was a drinking-problem that made his hands shake in the classroom. Both of them were school-teachers. She grew up feeling unloved, inadequate, and ugly. She believed anger was better than sadness and so she nursed her rage that spilled over onto the people she wanted to love, even when we met as freshmen in college.

I had grown up mad, queer, and vaguely nonbinary in an unhappy Bangali household where none of this was allowed. I had no language for OCD or abuse then, but I knew that whatever I was, it was wrong, that it was a synonym for obaddhyo (disobedient), and so I would be punished for it violently. At the same time, I nursed a certainty that this was unfair, a quiet rage that curdled into detachment and a hollow depression.

When J and I met each other, we found ourselves beloved. We were lonely, and then we weren’t. It was as simple as that. We weren’t the first person either of us had loved, or even loved well, but we were the first person we had tried to love unconditionally. What could be more romantic than that?

In Yellowjackets, Jackie and Shauna’s friendship is bookended by the same dialogue repeated to each other. The first time, they are at a raucous gathering with other teenagers. There is a crackling bonfire; Jackie has just used her influence to bring the team together after a fight, the girls have been going around saying nice and true things about each other. She tells Shauna, “You’re the only one who’s always been there for me. You’re the best friend I’ve ever had. You know that, right?”

The second time, Jackie is hallucinating, freezing to death in the snow just outside the cabin where the rest of the girls are sleeping. All she has to do is go inside, and she’ll live. Instead, she dies a brutal, meaningless death, literally the outsider to the group. Just before dying, she dreams Shauna has come outside to make up and bring her inside. The cabin is warm, the fire crackles, and someone puts a blanket over her, guides her gently to a chair in front of a fireplace. Shauna hands her a mug of steaming hot chocolate, and says, “You’re the best friend I’ve ever had. You know that, right?” It’s so eerily perfect. It’s when you know something’s wrong. As if on cue, the rest of the team, standing in front of her like a nightmare choir, chime in unison ‘We love you Jackie’. They have wooden smiles on their faces. It’s tremendously frightening. Of course it’s not real — it’s the correct ending, so it’s the one that doesn’t happen.

For J and I, being each other’s best friend we had ever had, and knowing that, was a feeling that was essential to our friendship. Knowing and being known by someone as a virtue in itself, being able to expect and demand priority from someone — we had never had that before.

Were you in love with her? one of my now closest friends asks. No, I don’t think so, I say.

But when I first put a foot out of the closet in undergrad, it was J that I called and told, I think I’m a lesbian and I’m in love with you. When I returned to Calcutta for summers, she was at the airport beside my mum holding a placard with postcolonial humour: Canadian Refugees Welcome Here. Jackie and Shauna trade a heart charm-necklace back and forth; J and I had matching infinity rings (I lost mine). She told her much older partner I would always be more important. She wrote me a poem comparing me to the half-melted part of summer ice cream and the yummy heart part of her every sweet dream. After we fell out, she kissed me, drunk and desperate, and I wanted nothing more than to get away from her.

We had a very queer friendship. Or alternatively, we had the most typical friendship you’d imagine for two women on the cusp of adulthood. It was everything until it wasn’t.

My favourite Nicole Sealey poem goes, ‘Though we’re not so self-/important as to think everything/ has led to this, everything has led to this./ There’s a name for the animal/love makes of us—named, I think, / like rain, for the sound it makes.’

We didn’t have proximity, so we overdid the repetition, exchanging a million i love yous and blank emails with subject lines like Call me bitch or Read at once!!!! We stayed up past bedtime so we could coexist for a bit in our own time suspended across the Atlantic. It felt worthwhile to have survived childhood, suicidality and isolation, because it had led us to each other. Our first attempts at autonomy, deciding the kind of people we would be, the way we would feel about ourselves began with each other. The biggest gift a fierce love like we had for each other gives us is the knowledge that we can be loved as the unspectacular people we are. The animal, that love made of us, was soft and relieved.

We fell out over something stupid. She disappeared after my first major break-up. I wasn’t there when her grandfather died. She avoided my calls. I was confused, then I was determined to reach her, then I was hurt and angry and bewildered, then I went cold.

Over time, as I’ve buried memories of my depressed years in Canada as an arts-kid stuck in a science student’s life, I’d also forgotten how our friendship was a blazing, living thing. Recently, I typed her name into the search-bar of my old email account and found over six hundred emails and chats — the ruined body of our friendship that bridged time difference and geography for years. I looked through them for evidence of who we’d been:

J veered wildly between extreme depression and overwhelming excitement about life. One day her boyfriend was pathetic, the next he was her soulmate. I buried myself in an overfull course load and ate my sadness: multiple large greasy anchovy pizzas daily, during finals. J was an immensely talented writer whose career as a novelist was already starting to take off. She got stoned and wrote me late-night emails confessing her terror that she had inherited her father’s bipolar disorder. I trudged through a blizzard to the nondescript animal-lab where I would watch rats respond to Pavlovian cues in a maze and record what they did. We graduated.

In high school, Shauna resents being contorted into something she doesn’t want to be as a byproduct of Jackie’s overarching influence. She doesn’t want to wear the red dress or play soccer or go to Rutgers but Jackie has already decided the colour of their dorm-room.

Like Shauna, no matter how much I shrugged it off, around J’s charisma people could feel forced into roles they didn’t want. She was the sharp pointed knife of intellect, so I had to be the airheaded but unexpectedly smart-scientist friend. At a birthday party we had thrown her, I made an obvious Mean Girls quip to make people laugh (It’s like I have ESPN or something). J reacted as though I was actually that daft. For a time, we were part of a trio until our other best friend grew tired of J’s casual meanness (You have no self-esteem, that’s why you’re always looking at dogs for validation).

I wonder who J would have been at thirty. If she had received the right care and matured into realising that ordinary people deserve kindness and don’t have to be special to prove it. What a relief it has been to grow older and accept that for myself, and by extension for others too.

Instead, J’s mean streak and defensiveness eventually alienated all her friends. By the time she was spiralling through a bipolar-induced breakdown, she had no one. We struggled with serious mental illness through our friendship, but by the time we knew the names to articulate it, we weren’t friends anymore. Over the next few years I’d see snatches of her life play out from a distance. Some of these I knew to be true from our own past discussions: J was working a management position at a faceless corporation and trying to get rich quick; she was doing stand-up. Others I heard second-hand, and sometimes from people who relished these stories like they were juicy gossip: she had thrown a heavy glass ash-tray at her boss and quit the corporation; she had been institutionalised against her will. On Facebook, J posted a long rambling note full of accusations and conspiracies.

One of the last times we tried to repair our friendship, J showed up at my house past midnight and ate cold daal-rice from the fridge. She talked incessantly without meeting my eyes and told me about the fascinating married woman she was sleeping with, how little she needed to sleep these days, and that the future was sparkling. Now, at thirty, I have been involved in disability justice advocacy for some time. I report on the intersection of public health and severe mental illness in India. I’m astounded at my self-absorption then. How did I not see her depressive and manic episodes for what they were?

Older Shauna is haunted by Jackie’s ghost. She sees her at nightclubs and in Jackie’s childhood bedroom when she visits her parents. In an interview, Melanie Lynskey, the actress who portrays her, says that to her the story of Shauna and Jackie’s friendship is a tragedy about never being able to repair that relationship that is all-encompassing. Shauna is stopped in her tracks by grief and chasing the ghost of Jackie because all she’d want to do is go back and be a different person, a better friend. She’s also living a somewhat twisted version of what Jackie’s life could have been: She married Jackie’s boyfriend Jeff, had a child, and lives in a comfortable suburban home.

Seeing our own dynamic strangely mirrored back finally gave me the words for how to think about J. J never met me with the accretions that make me feel like myself: the nose-ring, seven tattoos, more recently, an eyebrow piercing, an undercut. She never knew the nonbinary dyke I am now, writing for a living, on Prozac and Adderall, with a queer disabled community of friends, exploring non-monogamy, writing about lesbian sex intentionally, openly in fiction, writing a book even. Sometimes I feel like I ate J’s life. Like it’s because she vacated the space that I’m living a funhouse version of what hers was.

J introduced me to things I’d come to love later, in my own time: Sade, Doctor Who, macabre literature, speculative fiction, the uncanny, a love of the absurd, self-worth, queerness, gender-fuckery, editing and revising sentences. I don’t know that I would have turned into myself, ever would have left the deeply unhappy, good Indian Science kid version of me behind without having met her.

In the finale, digging Jackie’s dead body out, Shauna screams and screams. She regrets not having gone outside to call her back in. I feel like that scream has been stuck in my own throat for the past half-decade. I don’t even deserve to scream, because I just let her go.

We loved each other at a time we didn’t know love was important enough to let people fuck up and not take it so seriously. What do we do with the regret we feel at not having been able to be better people for those who loved the earlier versions of us?

I find myself dipping into magical thinking.

There were darker whispers about J too, ones that shook those who were still friendly with her and became the final straw in her eventual isolation. About things she had done, people she had harmed terribly. I don’t know what really happened. There is no way to parse the truth. I find myself thinking if we had still been friends, maybe she wouldn’t have been institutionalised. Maybe others wouldn’t have gotten hurt. J isn’t here to tell her story.

The truth is you can love someone long after they fuck up irreversibly. And my wanting things to have been different can’t alter that they weren’t and can’t ever be now. Although we’ve had abolitionists, transformative justice, and disability justice activists fighting for care-networks rooted in community as a concept, our collective imagination is still so far from making this real. Especially in India which doesn’t have the same histories of mutual aid or abolition activism rooted in Black communities subject to over policing.

I’m stuck on the question of what to do when people are unlikeable, unpleasant, and still deserving of care. People love to talk a big game about mental health awareness, but we’re not ready for the ugly realities of when mental illness manifests in ways that can be harmful to others. Who provides care to someone who’s alienated everyone? Who ensures they don’t disappear or die?

In her brilliant and radical book Care Work, disability activist Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes about the complexities and conditionality of receiving collective care:

“I think about the need for care that can be accessed when you’re isolated, disliked, and without social capital — which many disabled people are. I think about how power dynamics and abuse can creep into the most well-meaning care collectives of friends, and of my friends who need twelve to fifteen hours of care a day, which is difficult to impossible for most unpaid friends to provide. I think about the person I was lovers with who was an asshole about thirty percent of that time, who I still send twenty bucks every now and then because they are seriously disabled and can’t work. I do this because they are a queer and trans person of color who grew up working class who’s pissed off a lot of people, and they still don’t deserve to die alone in their own piss. I think about my friend who said, “I never want my ability to go to the bathroom to be dependent on how liked I am.” I think about how relieved I was to discover that the state I live in offered twenty-four hours of emergency respite care to caregivers — someone well paid by the state who could come in and pick up meds, do some home care, and fold laundry — that my partner and I could access if one or both of us had a medical crisis. I think of the disability networks where friends and total strangers on the internet bring each other soup and share meds and send money and how lifesaving that is — and what happens when someone is kicked out of that Facebook group.”

Same. I think about this too. Every time I casually refer to myself as a ‘crazy person’ as an act of reclamation and defiance against an ableist world that would prefer the ‘visibly crazy’ be locked up, or someone else’s problem, I feel J saying the words first. Inside me lives another woman. I am haunted by someone else’s rage and mad desire to stuff all of life in.

In music, the seventh and final mode of the major scale is the Locrian mode. It is the darkest sounding, most minor mode since so many of its notes are flattened. It’s rarely used in music because it never resolves. It sounds unfinished, like someone stopped playing or singing abruptly in the middle of a melody.

Jackie and Shauna’s friendship ended in Locrian mode. Jackie froze to death after a petty fight so they never got to make up or grow apart naturally. My Jackie disappeared so I didn’t get to reach out to her as the version of myself who believes in disability justice. In the end, like Shauna, I am left on a note of irresolution. I am haunted.

Obviously one person cannot mean all things. J is not a metonym for how many people we’ve loved have behaved in terrible ways — casteist, racist, homophobic, ableist. She’s not a metonym for how people are complicated or deserve redemption. Mostly I’m just recording that she existed. My Jackie, she did some bad things. I loved her very much. I hope in the end she wasn’t lonely.

Time Zones Week is a series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

Grief Exists in Its Own Time Zone

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

My body is in Brooklyn, but my heart is already in Los Angeles, and I can’t fucking sleep. Since I made the decision in December to move back to my home state, it’s like my circadian rhythm immediately got in line, even though it’s not happening until early spring. This…is a problem. I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s back up a bit.

It’s July, 2021, and my mother is here to visit. I haven’t seen her the entire pandemic; the longest time I’ve gone without hugging her in my life. The plan is for her to stay in Brooklyn with me for a few nights before we head down to Jersey to see my grandmother (Rho Rho, an affectionate nickname for Rhoda) and my Aunt Ilyse. We’re sitting on my couch in an apartment she has only seen over FaceTime. However, the joyous mood of our reunion is soon shifted forever, both in that moment and in my memory, when she tells me that what I’ve been fearing my whole life is finally happening — Rho Rho is dying.

This new information, of course, alters the tenor of the upcoming visit; it will be the second-to-last time I’ll ever see Rho. The muscles in my shoulders, already tense by nature, tighten like the strings of a violin, and a briny lump forms in my throat and that will not dissolve for weeks, as though I’ve prematurely swallowed some saltwater taffy. But something else changes during this visit; the seed of an idea is planted. I start to think about California, about my family. I start to think about home, and what that even means.

Now let’s zoom out, for a second.

There’s a reason people say things like grief isn’t linear, and you won’t feel this way forever, and there’s also a reason it feels like you’re hearing those things through a set of ear muffs when you’re in the moment. There’s no way out but through — damn, that’s another thing people say, isn’t it? But the reason these phrases are oft-repeated is because they’re true, and I’m saying this now because I’ve found it to be so, even though I’m not nearly “out” of the pain myself. I’m “in” it, still. Some days it feels like it’s been years since Rho died; some days it feels like it was yesterday.

The most common association many of us have with grief is those five famous stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This has not been my experience. I assume that perhaps, some of these stages are dependent on who is grieving, or the relationship between them and who they’ve lost. It is my belief that models like these aren’t meant to be taken literally but that they were created as a framework for people to work from and feel less alone. However, I think that often, the opposite happens; people think they’re doing something “wrong” if they can’t map their own experience on what people understand as psychological gospel, when in reality, there’s no right way to grieve.

Fast-forward, but just a bit.

It’s September. No, wait. It’s the beginning of October, or the end of August. Or maybe it’s just later in July? The threads of time have started to fray since last March, and now, it’s like they’ve completely snapped.

I’m on the phone with my therapist, dreading Rho’s passing while feeling guilty for dreading it because she’s in such pain. There’s a constant voice in my head telling me I should “take advantage” of the time she’s still here and ask her all the things I’ve never asked her, and then there’s the guilt again, asking me why I haven’t had those conversations yet in my 33 years, which leaves me a sobbing yet immobile mess on the couch. And then, after all these tangled emotions, I’m left feeling, of course, like this is just my new reality. I know I’m not the first person to go through something like this, but it doesn’t help; like so much universal pain, when you’re going through it yourself, it feels singularly sharp.

My brother flies out from California to say goodbye to her in the beginning of October and I take a bus down to Jersey to go with him. We sit on her couch while she sits in her pink arm chair; we talk about her childhood, astrology, and the afterlife. She says that “now is the time” to ask her whatever we want and that nothing is off the table. She’s serious, and the moment is serious, but I look her straight in the eye and I say, “Rho, cut the shit, you know what we all want to know: what do you think about aliens?” Even though she’s exhausted, her laughter is soul-deep, and my question gets another twenty minutes of conversation out of her about, of course, aliens. That was our relationship — I was her only grandchild who wasn’t a cisgender male, and we always had a special bond. She’s the only person in my family, aside from my brother, who could ever call me out on my shit without getting the cold shoulder, and in moments that needed a little levity, we could always count on each other to provide it.

When she dies a few weeks later, I swear I feel it happen. Everything starts to move in slow motion. I take time off to go to her funeral. Though I hadn’t planned on talking during the service, in the middle of the funeral, something tells me to say something. I tap my mother on the shoulder and ask if I can go up with her and my aunts; I tell a story about our last conversation, get a few laughs from the crowd. I feel her approval. I extend my trip from two days to five because I can’t bear to go back home; I need to keep helping sort through her things. At first, I can only cry in the shower, sitting on the floor of the tub; then, I’m crying everywhere. I can conjure her face, her laugh, so easily, and it knocks me over.

A few months later, for a completely unrelated reason, I will check an old email account that I haven’t opened in years. My heart jumps in my throat as I realize that Rho had this email address as well as the Gmail I’ve been using since 2015; something tells me that there may be a few unread emails from her. I spend a good 15 minutes scrolling, and I find four. Most are funny but unremarkable, but one stops me cold. It’s from 2019, and she’s recounting her day to me. She attended the funeral of a friend, and tells me the friend’s son-in-law and grandson both “spoke beautifully but honestly” about her. She writes, “They acknowledged her shortcomings but emphasized her many attributes. They injected much humor, which everyone appreciated and I have already mentioned to Ilyse that I would like that for me. I will let Diane and your mom know that also. I am telling you because I don’t want to rely on their memories, since they will be much older as I plan to be around for quite a bit more time.” Even though I hadn’t read the email back then, our connection had been enough; I’d known what to do.

All of a sudden, it’s the middle of November, and it’s been one month and one day without her, and I am mad at myself for missing the one month mark. Time speeds up, then slows down. I think, again, grief isn’t linear. I can still hear her laugh and see her face so easily, and it hurts, but I’m realizing there are certain things I may forget with time, and I start to understand that what they say is right — it won’t feel like it did at first forever. I’m not sure if that’s a good thing.

Time jumps again.

It’s nearly February. She died three months ago, or was it four, or was it yesterday? When someone you don’t see or talk to every day dies, it can be easier to forget they’re really gone; when you do remember, it hurts fresh all over again. I notice this without comparing; any loss is a loss. I’ve reached that point where people don’t ask how I’m doing anymore. My grandmother has no longer just died, I’m no longer in the understood grieving period, though I don’t know when this wound will ever fully heal. I think I’m just different, now.

But I have started to look toward the future with optimism in a way that I think she would be proud of; at least, that’s how it feels on good days. Other days, it feels like I’m distracting myself with thoughts of moving. I don’t know that either is a bad thing. There is no timeline for grief, though I’ve started to suspect part of my motivation for relocating is to get back to my roots; to heal bonds with my family and share the memories we have of her in a way that I can’t on this coast.

The closest thing to what I’ve been experiencing lately has been a small detail from The Year of Magical Thinking. Joan Didion and her husband were eating dinner together in their New York home when he died. After she returned home without him for the first time from the hospital, her agent and friend came over to keep her company and help her begin to inform the proper parties, including the newspapers. While Lynn was on the phone with the chief obituary writer for The New York Times, Joan, ever the Californian at heart, found herself doing what I call “time zone math,” wondering — had John also died in Los Angeles? “Was there time to go back? Could we have a different ending on Pacific time?”

The majority of my life has been spent in California; the entirety of the time I lived there, Rho was alive. While moving there won’t bring her back, nor will living on Pacific time create a “different ending,” it will create a different beginning. Her death shifted my perspective about my priorities and about my future. And while my heart breaks over all that I won’t get to share with her, I’ve started to think about both her, and myself, like those stars whose light we admire, thousands of years after they’ve actually died. I choose to believe that everything I do will reach her, anyway. We cannot bend time to our will, nor can we push grief along; but in the grand scheme of things, time is meaningless, anyway, isn’t it?

Time Zones Week is a series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

We Call It Time Travel

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

It’s 8pm on a school night when I show up at the bar holding a bouquet of pale purple flowers. My brand new girlfriend sits on the outdoor patio with her best friend, celebrating the job she just said yes to that afternoon. I did not tell her I was coming. It is a 30 minute drive from my house to this bar, an hour round trip. It’s not like I have time to spare — I have so many work deadlines, I am so behind on everything, I theoretically should try to sleep more than four hours tonight — but it also never crossed my mind to not bring her flowers tonight.

“Baby!” she exclaims when she sees me. She hops out of her chair and throws her arms around me, she kisses me and I can feel her grin against my own.

“You’re so nice to me,” she says into my hair. I laugh, thinking back to our first date, just six weeks earlier.

“How am I supposed to be to you?”

She knows exactly the moment I’m referencing. For just a minute, we’re not in the bar, not in this time frame at all but somewhere else.

Her kitchen. Late late night. Just the two of us. Right at the beginning. She smiles that coy closed mouth smirk I have memorized in the weeks since then and holds my gaze. She nods. I nod back. She grabs my hand and squeezes and we sit down and we don’t stop holding hands.

And then we’re back in the present.

“I want to call you babe, but that feels a little weird now, do you know what I mean?”

We’re at her house. It’s the morning after our first date. She’s standing in the kitchen, making us tea. I’m curled up on the couch with her tiny dog, stroking his soft velvet belly. We haven’t fucked yet. We’ve been friends for seven and a half years. I’ve called her babe so many times before; I call all my friends babe.

She smirks at me. Her Scorpio soul is used to becoming all consumed with another person. I’m still so Capricorn careful. I will let go of that soon, but I’m not there just yet. I haven’t quite decided what version of this story I’m going to live.

Here’s how this goes in a different timeline: I keep her at a steady distance. I insist we see each other only once a week for the first few months. I do not lean into the lesbian stereotypes, I do not let her know all the things I desire, I do not get honest with myself about what I need. Maybe I tell her to keep dating other people. Maybe I say I’m not looking for a co-parent. Maybe I insist I can keep doing everything just fine on my own. And it’s not that that’s not true — I am so competent. But what if I want to need someone?

In therapy, I’ve been learning about “opposite action” as a strategy to manage my anxiety. It’s exactly what it sounds like. You look at the coping mechanisms you rely on, you accept they are not serving you, and you do the opposite.

What is the opposite action of thinking I can control the beginning, middle, and end of my own love stories?

Here’s the thing about the other timeline: I have tried it before. I really thought I could protect myself from the potential side effects of falling in love if I was just vigilant enough. But I was so careful in the past, and it ended in heartbreak just the same.

I let myself call her babe. It does not feel weird. It feels like I’m falling. It feels like choosing the correct timeline.

Nine years ago, I was in love with a different girl.

Back then, I lived in a different city and I had a different job. Late at night, I’d sit on this girl’s sofa in the house she shared with five housemates, and we’d read to each other from our works in progress on our laptop screens. I loved her, but I never said it outloud. We built a world together. When we broke up, that world disappeared.

I think about this all the time. How a relationship is its own time zone. How we build worlds with the people we love, and we are the only people who inhabit them. And when something ends, those worlds disappear. It’s not like love is a static place we bring new lovers to every time we feel it. Love is a creation that occurs between the people feeling it. To love someone new is to agree to travel somewhere that doesn’t exist yet together. Love is a brand new place we choose to go every time.

“I’m not a poet,” I tell her, the night we write each other love poems.

It’s after midnight and we’re both drunk and sloppy. I’ve traded my black velvet dress for a cozy black onesie, mascara flaking onto my cheeks. She’s traded her black velvet dress for a tight red onesie, matching red lipstick smeared on her teeth. We’re folded into each other on the couch, giggling about inside jokes we’ve created over the past six weeks. Her small dog is curled between us; he’s sleeping. I want another gin fizz, but I can tell I’m trashed, so I settle for a Diet Coke instead. She smells like the cigarette she went outside to smoke. We spent the past four hours on FaceTime with two of my best friends who live in different states, a virtual happy hour tradition we began in the early days of the pandemic and have held onto. I’ve never brought a date to virtual happy hour before; I’m delighted it went so well.

And now it’s just the two of us again.

She takes out her sketchbook and says we should write each other poems, says we should do the writing exercise I like where we switch off offering a word and then have a limited amount of time to write using that word. I would do anything for her. Five minutes later, we’ve written each other love poems. We read them out loud. Her dog stays sleeping.

Six weeks ago, I didn’t know what her inner thigh crease looks like. Six weeks ago, I didn’t know the way her voice sounds when she says hot, when she says baby, when she says sick, when she says I love you. Six weeks ago, I never would have been sitting on her couch after midnight, reading her a love poem, insisting I’m not a poet. We’re creating this world out of thin air, this space that literally did not exist before we decided to make it. This new world only exists because we say so.

“We make the rules,” she often says, and I can’t stop smiling. “No one has ever felt like this before,” we tease each other, and we laugh because of course we’re being hyperbolic but also, isn’t it true? No one has ever been me and her falling in love with each other as the world ends so — no one has ever felt like this before.

“If you knew how your life was going to play out, would you change anything? Are relationships still worth it even if they eventually end in heartbreak?”

We’re in the car, and she’s describing her favorite movie: Arrival. I don’t like movies and I rarely watch them, but I already know I’m going to watch this one because it matters to her. I don’t like games either but soon I will learn to play Dominion because it’s her favorite. She’s not Jewish, but she offers to come to synagogue with me because I’ve been trying to make it a routine in Portland and it’s scary to go alone. She tells me she doesn’t love talking on the phone, but we spend hours doing just that while she’s away with her family for Christmas.

Arrival is about aliens coming to earth, she tells me. “But it’s really about communication and how language shapes the way you experience life.” She’s a speech pathologist, just like my mom. She’s a Scorpio, just like my mom. We’ve been friends for seven and a half years, we’ve been to all the same gay dance parties, and we’ve shared all the same gay gossip, but we’ve never been close before. She both feels familiar like family and brand new like I made her up.

“And also it’s about choices,” she says.

We’re in the car, because I just picked her up from the airport. We’re both educators so the week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve is time off, and we’re going to staycation at her house. She’s supposed to go on a date with a co-worker’s friend in January, but when her co-worker texts about it she explains she no longer wants to.

I fell in love over Christmas break, she writes.

Well fuck yeah, her co-worker writes back.

We stay inside for so many days and we talk and we fuck and we laugh and we cook a Dutch baby for breakfast and we watch Arrival and we fuck more and we roast a whole chicken with oregano and fennel and tomatoes and so much butter and we learn each other and we start to say we feel like we’re time traveling, like we’ve lived different versions of the same lives, or similar versions of different lives.

On January 1, we leave her house for the first time in days and we take her dog to the off-leash park and the sky is crisp blue and the air is cold and we listen to Taylor Swift in the car and we are happy.

We keep finding things we have in common. We keep finding differences to live in, too.

We replay versions of old relationships because we are 32 and 33 respectively, and this is not our first time at the rodeo. I’ve always been obsessed with who owns what in a breakup — what do we keep, what becomes part of our individual makeup, and what do we surrender? We have both collected bits and pieces of other people over the years. I ask her if it’s okay to show her nudes I took years ago, slutty selfies I’ve sent to past lovers, and she laughs, nods yes.

“I’m a slut too,” she says, teasing me. “I’m not into virgins. Show me all your old selfies.”

She lets me go through a box of nostalgia from her childhood and read her old journals and look at photographs she took of her second girlfriend ever. I can tell 16-year-old her loved this girl so much. I wonder what these teens each kept from their relationship when they broke up. I wonder how this girl, a girl I will never know, helped shape the girl I’m in love with now. I wonder how everyone before her helped shape me.

“I wish we’d started dating sooner,” I say, thinking of all the time we could have already shared. But she shakes her head, no. “I think we met at the exact right time,” she says. We’ve known each other for years but we’ve never been these exact versions of ourselves before. It is these two people who needed to fall in love. I understand. She’s right.

“Your priorities change in your thirties,” my dad always said. I tell her this and she laughs and nods. We say this almost daily now. It’s part of the life we’re building together. We share it with our friends when we tell them we’re in love and they smile politely but I can tell they don’t quite believe us. We don’t care.

“We’re unhinged dykes at the end of the world,” we tell each other. “We’re sluts in love!”

She says “I love you” for the first time over the phone at 5 a.m. when she’s in California. We’ve been dating for five minutes; we’ve been friends for so long; we’ve been in love, we’re already in love, we choose to fall in love, what is love? She’s drunk and honest and I’m not freaked out.

I pause for a moment.

I decide to dive off the fucking cliff.

“I love you too,” I say.

Then I read her Don’t Hesitate, by Mary Oliver. I’ll write it in her Christmas card a few days later. Why not. Truly, why the fuck not!

Being vigilant didn’t keep me safe. Being careful never stopped my heart from breaking. I’m 33, and I don’t want to be in love if it’s not the all-consuming kind I felt when I was 19. I didn’t always feel that way, but I do now.

Are relationships still worth it even if they eventually end in heartbreak?

She hasn’t asked me that question yet. She hasn’t explained the plot of Arrival yet.

When I was writing this essay, I searched my inbox over and over, looking for the email she wrote me in California that described the plot of her favorite movie. We wrote so many emails the week she was in California.

She reads all my old work, and I remind her my brain has been changing this whole time, that the things I thought even just a year ago are not necessarily the things I think anymore. A year ago, I was happy with a person who would eventually cheat on me. A year ago, I wasn’t sure I could justify having a baby anymore in a world that looks like ours. A year ago, I was the same, because I am always me, but I was also different, because that’s the reality of being alive.

I tell her how Michelle Tea once told me that being a writer means growing up in public. I’ve written that Valencia is one of my favorite books, that it taught me how to be myself when I was just a baby dyke. “Is that true,” she wants to know. “Yes, it’s true.” She tells me how she read Valencia as a baby dyke, too. “I wonder if we read the same chapters at the same time,” I say, and we giggle in delight, charmed by the idea of our teen selves becoming our adult selves in cosmic unison.

We talk about how people stay the same. We talk about how people change. I want to know her whole life. I send her writing prompts. Tell me about a formative life experience, I write. Tell me about the weirdest sex you’ve ever had. I’m so certain she’s written her personal plot summary of Arrival in these emails; I can envision the paragraph. It is stamped neatly across my brain. But when I finally ask her, she says that’s not what happened.

“I told you about Arrival for the first time in the car when you picked me up at the airport, babe,” she says. I believe her, but that’s not how it happened in my mind.

On January 1 last year my dad died. I was in a different dyke’s bed when my mom called me at 2 a.m. in Portland, which was 5 a.m. in Boston, and she told me that my dad was dead. I ruminated on this all year. My dad died some time between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. on the east coast. That’s 8 p.m. and 12 a.m. on the west coast. That means while I was happy, while I was playing with my new puppy, while I was having sex, my dad was dying. The logic of it is fucked.

But what if I imagine a different sequencing.

My dad died and I was happy. My dad is dead and I am happy. It is hard to write that down — how can I ever be happy because my dad is dead? But it is not because; it is at the same time as. I hold multiple universes in my heart. I think my dad would like that. I think he would laugh at me and remind me I’m in my thirties now, and despite all my protests, some of my priorities have shifted. I think he is right.

I was obsessed with Rilo Kiley in high school. I was obsessed with The Shins, with The Decemberists, with Wilco, with the boys in bands who introduced me to so much indie rock and who I dutifully watched play so many shows in so many church basements.

My girlfriend is the lead singer of a queer cover band. She puts a Jenny Lewis song on the first mix she ever makes me. She takes out her guitar and plays covers just for me. She learns the ten minute version of All Too Well because I love it. We scream-sing along to songs I’ve loved for decades in my car. I tease her that she’s my dream high school boyfriend.

One night after she’s fucked me for hours, and I’ve fucked her for hours, and she tells me she notices my lips get cold when I’m really deep in sub space and that’s how she knows it’s time to untie me from the bed, and I am touched that she is learning all the ways my body can be, when she cuddles into me close and I hold her and stroke the fuzzy back of her head, when she’s sweet and soft, she says “Hey Google, play Rilo Kiley,” and then I’m 16 again and my favorite band is playing, but I’m not 16 I’m 33, but when I was 16 she was 15 and I lived on the east coast and she lived on the west coast but we both listened to this album on repeat over and over, we were both forming our selves and we didn’t know each other yet and we didn’t know that 16 years later we’d be lying in bed, two dykes in love, singing about the Absence of God together.

It’s 2022, and I’m obsessed with this song, specifically the lyric that goes: Rob says you love love love, then you die.

“I think it’s supposed to be sad,” I say to her while we’re driving from her house to mine one rainy afternoon, “but I think it’s kind of beautiful? Like, what else would be the point? Literally what else are we on earth for?”

She agrees with me. “I think it’s kind of a young perspective maybe,” she says. “Like when you’re young that sounds sad, because you die, but when you get older you realize everyone dies and if you can love a lot before you do, that’s fucking great.”

I hit repeat and the song starts over. She lets me hit repeat as many times as I want.

Near the end of the celebratory school night at the bar to celebrate her new job, we’re talking about secure attachment because we’re gay and trying so hard to unlearn all of the bad patterns we’ve picked up in three decades of being alive, and I’m explaining my theory that no matter how much you love a person if you don’t want the same things your relationship is going to be really hard, and then I find myself talking about my dead dad, and how he bought my mom a dozen pink roses every single Friday for the entirety of their relationship, all 38 years of it.

Growing up, I knew that the end of the week meant Shabbat and it also meant my dad’s bouquet for my mom. He’d pick it up on his way home from work, and she’d cut the stems and put them in a vase. The flowers would go next to the Shabbos candles, and I’d gaze at them as we said the Jewish prayers.

I’m tempted to write: As a kid, I wondered what it would be like to have someone love you so much they wanted to buy you flowers every week for 38 years, but that sentence is not true. I did not wonder. That love was right there in front of me. I’m lucky. I bet after a while my dad did not need to remind himself to bring my mom the flowers; the romantic gesture probably became natural, instinctual, part of his routine, part of his life. It never crossed his mind not to bring the flowers, just like it never crossed my mind not to bring a bouquet tonight. Love as muscle memory.

“My dad liked buying my mom the flowers,” I say to my girlfriend and her best friend. “It was easy for him. And my mom loved receiving them. She understood what they meant.”

If either of my parents had not enjoyed this ritual — if my dad thought flowers were frivolous, if my mom found the gesture boring in its repetition — it would not have done its job. But they both wanted the same thing. I know my parents’ relationship wasn’t perfect, but it wasn’t really hard. Growing up adjacent to it, I would say for the most part, it was actually pretty easy.

The evening dwindles to a close. My girlfriend’s best friend thanks me for sharing the story about my mom and my dad’s flower ritual. She says she’s going to pick up flowers for her girlfriend on her way home. “I want to show her how much I love her,” she says. We all hug goodbye, and then my girlfriend and I are alone.

She cradles her celebratory bouquet in one arm and laces her fingers through mine with her free hand. We walk toward her car; once we get there she offers to drive me to mine. I climb into the passenger seat and we spend a not insignificant amount of time gazing into each other’s eyes before she puts the key in the ignition.

It’s six weeks ago. We’re back in her kitchen. Late late night. Just the two of us. Right at the beginning.

She’s drunk and pouring a glass of water. I’m less drunk, but I want one too. I ask if I can have my own glass and she immediately hands me the one she just poured for herself, reaches into the cabinet to pull out another jar. I’m struck by the gesture, simple and obvious. So generous. So easy. So the opposite of what I’m used to.

“You’re so nice to me,” I say to her, and she stops pouring immediately and whips around to stare me down.

We have been friends for so long. She knows about my most recent ex. She knows about my ex before that. She knows about my fucking ex before that!

“How am I supposed to be to you?” she asks, head tilted, eyebrows raised, not sweetly but more of a challenge.

She dares me to shirk away from what I deserve. In that moment, she is just as much my friend of seven and a half years as she is my brand new date. In that moment, I already know she loves me.

I bite my lip. Smile slowly. Blink. “Right,” I say.

She nods. I nod back. She grabs my hand and squeezes and we sit down and we don’t stop holding hands.

And then we’re back in the present.

“Can we take turns buying each other flowers every week for the rest of our lives?” she’s asking me.

I nod. She nods back. We are here, and we are twenty years from here, and we are five years before here, and we are, we are, we are, we are.

We call it time travel but I think it might just be falling in love.

Time Zones Week is a series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

To Travel, Like Light

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

You die when your spirit dies

Otherwise, you live.

I repeat these lines from Louise Glück over and over again in my head. The line comes from an incredible poem called “Averno”, in the book of the same name. It’s my favorite line from the poem. I’m preparing for a reading I’ve been asked to perform at, and my own words escape me. I reach toward old comforts after getting rusty from more than a year of no performances.

So much of my experience of poetry is wrapped up in time. From sneaking to write poems at work or in school, to writing poems about different periods in my life, trying to revisit them like a researcher.

The reading I’m about to do is in a different time zone, so I’m up and ready on Zoom at 10 p.m. my time, listening to the musical guest perform her rich music. My heart is in my throat. I keep panicking thinking about the last time I did a reading where I felt the breath catch in my chest like a mouse.

I’m trying to be present for the poets that are performing before me because I think they are phenomenal. The language transcends the miles between us as we Zoom in from our separate locations. Poetry, for me, is about all we can encapsulate within a sound. A mood, a dimension, a question, a time frame.

Please welcome Dani Janae to the virtual stage! the emcee for the night croons, and I take a deep breath, swallowing the tension.

I try not to look into the camera, still, I smile, thank the emcee, and begin.

As a young poet, I first fell in love with the work of poets like Emily Dickinson. It is horribly cliche, to be a lesbian that loves Emily Dickinson. I did not gravitate toward her work because I understood it; it was because I felt it. Poems like “Hope is the thing with feathers” and “I am nobody, who are you?” were of course poems I read as a student of her work, but the poem that caught me was “After great pain, a formal feeling comes-”

That poem ends with the lines: “As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow –/First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –”

All of the pain I held in my body let out a brief sigh. I did not let go of it then, and maybe have not let go of all of it to this day, but it sounded off in my chest because it recognized something in the words of Dickinson.

Dickinson was born and lived in Amherst, Massachusetts, which means we lived in the same time zone, years apart from each other. I wonder if she wrote early in the morning as I did, just as the sun is tempting at the edges of the city. I wonder if she had coffee with her poetry, if she set a timer, watched seconds slip. Maybe she just let the words come, fully devoted.

For many years, pain was the only thing that made sense to me, I lived in anticipation of the next blow. I didn’t talk much as a child and still don’t as an adult. It was in poetry that I found my voice, the bravery and strength it took to speak. Of course, I wrote bad poems, I wrote silly and sore poems. I just wanted to unburden the levy. I wanted to feel something other than the immenseness of my despair. When I wrote poetry and read it to myself, I felt a sense of pride for the first time in my young life.

When I needed it to be, poetry was therapy. Now that I’ve worked through many years of actual therapy, poetry is a place where I can express my emotions, but with a different end in mind. Just as Dickinson reached across time and our personal differences to reach me, I want to be that voice to someone who needs it.

The poems I read at the reading are from a new manuscript about sexual assault. It’s late, so I’m getting sleepy, and being in that state makes me emotional. So, I end up embodying a lot of the feelings I’m trying to express through the poems and fight back tears.

I’ve jumped time. I’m 22 again and there’s a policeman at my door, I’m trying to tell him what happened to me without looking at him. I’m thinking of grief.

In her poem, “Grief Work,” the poet Natalie Diaz writes:

“I wash the silk and silt of her from my hands—

now who I come to, I come clean to, I come good to.”

I think of all the ways I had come to people in the days, hours after my assault. None of them clean, none of them good. I had not done my grief work. I was hiding. I love what Diaz has to say about the poem, how she refers to grief as “the beautiful terrible,” a wilderness to be washed clean by.

Diaz also talks of bringing, experiencing your grief with the body of someone dear to you. I used to think that this was a means of doing harm. I used to think I had to be void of grief before I could touch another person without hurting them. I was afraid to make any kind of connection because I had a connection with the person that assaulted me, he was a friend. He told me he loved me moments before.

When I read the poems I had brought to read that night, I looked over at the chat in the Zoom window to see what people were saying. It was a chorus of repeating lines back to me, or thanks for being vulnerable and sharing this caliber of work with them. The emcee encouraged us to follow each other on Instagram and Twitter, so I get to see just how far spread we are, where we all are coming from.

The evening fades, it is nearing 12 a.m., it is nearing 9 p.m. We are hearing each other in the same instance, at the same speed, but at a different time. By the end of the reading, it is tomorrow on the east coast.

Sharing these poems was a means of touching my grief to someone else’s. A poet after me reads a set of poems about body dysmorphia, and I feel their grief of the body too. They are somehow in my home with me, each of us holding something that belongs to the other.

In her poem “The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feelings.” from The Renunciations, Donika Kelly writes:

“I stood in the mud field/ and called it pasture. Stood with a needle in my mouth/ and called it a song.”

I think about calling a thing by what it isn’t. I tell myself it is only really 9 p.m. where I am and I’ll get enough sleep tonight. I think about “love” in the mouth of a man that acted in a way that directly negated the sentiment.

Poetry always finds me where I am at, always lets me fall on my knees before it and kisses my forehead. I end the night with a poem that conjures tomorrow. It is tomorrow where I am, after I’ve washed my face and brushed my teeth, put my hair in a pile above my head.

I promised myself tomorrow after I left the courthouse all those years ago. I didn’t know it then, but a version of myself I did not know yet said: “stay.”

I said “tomorrow” and so it was. I conjured another day of living by speaking it. Another day to breathe and write, to come clean, to come good.

Time Zones Week is a series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

Closing the Distance With a Dash of Salt and Cumin

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

In the middle of a pandemic, 8,000 miles away from Dhaka, Bangladesh, I craved my favorite dish in the world: beef bhuna, a curry made of tender meat and rich, spice-packed gravy. I started dreaming of it almost every night. I was feeling picky about the taste. I couldn’t just take the subway to Queens and get it from a Bangladeshi restaurant — it wouldn’t taste like home. I’ve eaten a lot of beef curries in my life. But somehow it never compared to when my mother or grandmother cooked it.

By the time fall arrived in the northeast, I reached a point of extreme homesickness. I hadn’t seen my family in almost two years. It was frustrating that I couldn’t time-zone-leap like I had throughout the last decade of my life, having attended both high school and college abroad. Jet lag was a regular mental state — but here I was, not even able to leave my Brooklyn apartment, let alone buy plane tickets to go hug my family or pile spoonfuls of rice and beef onto my plate.

Eventually I took the plunge to just try making it. I chose a simple recipe. I went to a grocery store nearby, picked out stew meat and onions, and checked off the spices in my cabinet. I chopped onions, swallowed back tears, and marinated meat with spices and yogurt. When I was cooking the sauce, I noticed the yogurt forming cloudy clusters. Trying not to let this setback get to me, I simmered the gravy according to the recipe and finally, after a grand six hours of marination and three hours of cooking, it was time to taste. It smelled alright, and I was salivating at the thought of finally uniting with the one I loved. I took a spoonful of meat and sauce and gently poured it onto my plate.

It was not good.

Perhaps there was another route: Why couldn’t I just ask my mother? Pride, mostly. I hated relying on parents who created a home where my queerness was never welcome. I was too stubborn to admit I didn’t know how to do something my mother had basically perfected over the years. Everything I knew about Bangladeshi cooking was self-taught until this point. I’d especially started working on my skills over quarantine fueled by the intense longing for a feeling of home, the inability to travel in the foreseeable future, and anything made by my mother or grandmother a distant memory and my favorite beef bhuna a literal dream. I’d started with the basics: daal. Slowly, I expanded my horizons a little bit using YouTube videos. I made aloo paratha, fried flatbread stuffed with potatoes and spices. Shahi tukra, a dessert made of caramelized toast soaked in milk and sugar syrup. Keema, a ground beef curry where all you had to do was add turmeric, cumin, and chili powder, over fried onions and potatoes, and the stove would do the work. It went well, until of course, my disastrous attempt at beef bhuna.

I was back at square one.

I went a few weeks pretending it was okay. It was just one dish. I didn’t need it. I’d be able to visit Dhaka soon enough. Except. COVID cases in New York were on the rise, and vaccines hadn’t been distributed yet. I wanted to go home, even if it meant I would be bombarded by questions of when will you get married? by my relatives.

I debated 50 times before I hit the call button, my stomach in knots. I checked the time. 9 a.m. would be 8 p.m. for Ma, an acceptable hour. But this call required me to swallow my pride. Was I willing to do so — over beef curry of all things? Ma picked up even though it was dinnertime. I got past the small talk and blurted out my question.

“Can you teach me how to make beef bhuna?”

Please don’t laugh or question my cooking abilities, I prayed to the culinary gods. She didn’t do either. She just said, “really?”

I showed her the recipe I’d used. She said: “This is mostly similar, but there’s one other thing. When you fry the onions, make sure you throw in the spices there as well. Not just when you marinate it. Especially the cumin, that’s important. And before you take it off the stove, add salt. Beef needs more salt than you assume.”

“Ohh, okay,” I said, jotting down notes.

“And taste it before you turn off the stove. How else will you know if you hate it or not?”

“Yeah, good point,” I said. “The yogurt formed these ugly clouds when i cooked it — do you know anything about that?”

“You just have to beat it with a fork for a little before you add it and it won’t do that.”

“Oh.”

“You can call me, you know,” she said. “When you make it.”

“Eh, it’ll be around my dinner time — my 5 p.m. is 4 a.m. for you.”

“That’s okay,” she said. “I don’t mind.”

Late night calls on either of our time zones weren’t a regular occurrence, but with both of our reckless sleeping schedules, we did subconsciously know we could call the other at strange times on the clocks on our respective ends. It was something she had normalized, with a family scattered across time zones. And while I didn’t usually call Ma randomly in the middle of my day, I realized there had been times when I’d woken up from a nightmare and knew she was awake, which gave me reassurance I could talk to someone at 3 a.m. if I wanted to. Even though it was unspoken, she had willingly internalized time as a sacrifice in order to breach the gap — in a way, perhaps I had internalized it, too.

The next day, with Ma on my phone nested on the counter, I tried to cook as she slowly gave instructions. We both pretended she wasn’t struggling to keep her eyes open. As she instructed, I beat the yogurt before adding it to my marinade. I fried the onions with all the spices and made sure I added plenty of cumin. I timed it to precision, checking my phone frequently, but knowing I needed to have patience. And finally, before turning off the heat, I added salt, and tasted it to make sure it was okay.

“Moment of truth,” I said, noticing the sun coming up behind her.

I picked up my spoon and pretended to give her the first bite before taking my own. When it hit my tongue, I was overwhelmed by the rich flavor and heat in the sauce and the fact that the meat melted in my mouth. It was the right amount of spicy and honestly, delicious. It wasn’t as good as my mother’s or my grandmother’s, obviously.

“I’ll rank it a solid third,” I said.

“When you come home, it’ll be the first thing I’ll feed you,” she said.

“Can’t wait,” I said, trying my best to hide my tears.

She snored lightly in response.

This evening started a regular twice-a-day FaceTiming routine that extended beyond just “how are you’s” and “I’m alive’s.” Once during her day and my night, once during her night and my day. Sometimes at random off-hours. I took Ma to get mochi donuts with me to Chinatown. She called me in the middle of watching a movie to ask where else she’d seen every other actor. She took me to get her first vaccine shot.

As we started bridging the time zones through more regular calls, I started gaining hope that someday I could talk to her about my queerness, which I’d never felt like I could do before. In between conversations, I snuck in details about never feeling like I could marry a man — and that I found certain celebrity women attractive. The shift didn’t occur overnight, but as we confided in each other about our days and daily ups and downs, I felt that we could have more intentional conversations about my identity sometime in the future, even if it took multiple sittings and patience on both of our ends.

I finally received my own vaccination in April 2021 and booked flights to visit Dhaka in May. Ma waited outside the arrivals gate and I jumped into her arms. It felt surreal taking in her presence — it’s still weird that I’ve been three inches taller than her for a few years now. But she’s such an adult in my life the physical size difference doesn’t matter. The hug conveyed what words couldn’t — it was a huge relief to be able to close the physical and time gap again. It was also different from any of our other “welcome home” hugs. The pandemic had thrown timezones upside down, and in not knowing when we’d physically seen each other, we had grown closer than ever emotionally.

At the apartment, Ma brought out the beef soon after I’d showered. The first bite was as divine as I remembered, even in my jet lagged state. I tore a piece off with my hand, mixed the gravy, and made a little ball of the sauced up meat with a bit of rice and took it into my mouth. I could taste the individual spices — the cumin and chili powder bringing the heat, the coriander and garlic and ginger adding the much needed pungent punch while onions added a layer of sweetness and finally the sprinkles of salt and pepper completed it all. I looked at Ma, and she was watching me eat intently, the joy of having me back here eating her food clear in her eyes.

Time Zones Week is a series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

Time Between Us

Time Zones Week – All Artwork by Vivienne Le

My partner and I started our relationship at a distance. C was on Eastern Time. I was on Mountain Time. He was always two hours ahead and sometimes I asked, Was it a good two hours? What will happen? Will I like it?

During our very first conversation, C said, I promise I’m good. He said, Do you want to see a letter of recommendation? The letter he showed me was from his elementary school music teacher. She wrote: C is talented, but disruptive, talks too much to his classmates. I’m six years his junior and was a baby at the time, disruptive, probably, but not with words.

Long distance relationships are hard in obvious ways and easy in unforeseen ways. Hard because bodies because touch because the logistics of a hug. Easy because most things are beautiful from afar. I like looking at spiders on the internet and I can drink a cup of tea while I watch a video of a fire burning a whole coast to the ground. Once, in the Midwest, I stood on a balcony with a glass of Syrah and saw a drunk tornado swaying its way through a cornfield; I took a photo with steady hands.

C is from Kentucky; I’m from New Zealand — our homes are separated by eighteen hours. He’s six years older than me, but sometimes five. His birthday is in December, mine is in July, but we were both born into the winter.

Six years isn’t long, but he was born into a world that had a Soviet Union and one that was still fighting the Cold War and one in which New Zealand didn’t yet have access to the internet.

C had a sick mother. He grew up fast in the way we do when our adults need us to. Growth is mathematical and fixed in some ways and also emotional and fluid. As a kid, C learned about illness and aging how flimsy the façade of adulthood. His body grew fast, too. He was taller than the other kids, his voice deeper, his biology racing to catch up with his brain.

I grew up slowly and then all at once. I grew up according to man-logic. I turned 18 and was suddenly an adult, not because I was officially legal, fair game, but because my mother got sick, too, and I found myself with brothers to care for, a diagnosis to research, and still school to graduate.

C and I talk about our mothers’ sicknesses in different tenses. I use the past and he uses the present, but the truth must be somewhere in between. A new tense, for things that have already happened but that we carry with us through time.

Sometimes I try to figure out exactly how much time there is between C and I, but it differs depending on place, on whether you account for those eighteen hours, or daylight saving, or leap years. It differs depending on whether it matters that I was born three weeks prem. On whether you account for the way he put his life on hold to move across the country for me. Depending on whether it matters that it takes me two days to Google something he can find in ten seconds or whether you account for the fact that I drive double his speed or that he can drink coffee as soon as it’s made while I have to blow on the surface for half an hour. It differs depending on whether we’re having kids. On how long my PhD takes. On how long he’s willing to wait for me to decide what we’re eating for dinner. It differs depending on whether girls really do mature faster or whether that’s just an excuse for boys to behave badly. It differs depending on whether you’re measuring in imperial or metric.

Leap years exist because there are two different time cycles involved with the rotation of the planet. The first is the time it takes us to rotate on our axis: 24 hours. Clean. The second is the time it takes us to orbit the sun: 365.24 days. Messy.

When C moved to be with me, we were still operating on different clocks. He woke late, the morning already brewed, whereas I woke before the light and drank coffee in the dark. He wanted to stay up deep into the night, but my eyes have always tried to close with the sun. He left dishes sit in the sink until morning. He did his laundry most days, half-loads. He didn’t shower first thing.

It seems so trivial to bring up cutlery when you’re in love. These are the little things we let build and grow. They’re small until time has its way with them.

That extra 0.24 of a day, a quarter, almost, was accounted for by problematic queer icon, Julius Caesar, who announced that there would be an extra day every four years and that this would solve the problem of time, almost. 0.24 is not quite a quarter, see, it’s a sliver, 0.01, away.

Ideas do not function outside of time, but they are not strictly beholden to its passage. They’re something different, inflatable, transparent, which doesn’t make them less real than something tangible and tethered to time and space, but it does make them harder to define and communicate. I can give C the dish soap and it’s the same bottle in his hand as in mine, but it means something different to each of us.

C says, We have never had a relationship problem that was not communication-based. I say, My problem is that you are taking all of the cups in the house and leaving them in different rooms.

But he’s right. My real problem is that my idea of him does not hoard glasses. My real problem is that I am holding him accountable for the difference between my idealised version of him and the tangible one.

C is a better communicator than me. He knows what he feels and can articulate it. Whenever I try to grab hold of a sadness or fear it falls through my fingers like sand. C is always asking me what’s wrong before I’ve figured out that something is.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII was informed of the misaligned seasons courtesy of Caesar’s temporal band-aid. Greg, in an incredible display of Masculinity™, skipped the world forward ten days and decided that leap years would not occur on years evenly divisible by 100, unless they were also evenly divisible by 400. He called this the Gregorian calendar.

My friend, T, was born on February 29 and is (on a technicality) only seven years old because her birthday happens once every four years. Once, she said, At the rate the world’s going, I’m not going to make it to adolescence.

When I was 21, I dated a man who was developing a program that would monitor and report to the public the daily increase in corporate carbon footprints. He was twelve years my senior. He said, But you’re wise beyond your years, and, You’re so mature for 21, which made our age difference flattering to me and still creepy as hell to everyone else.

T was the only person to tell me the age-gap wasn’t great. She said, about him, He’s operating on DiCaprio logic. He understands time as a masculine issue and age as feminine one.

Despite the fact that T is seven, we’ve been friends for ten years. Friendships almost get to exist outside of time in a way that romantic relationships cannot because: Are you going to move in together. And, Get married? And, Have kids?

Time is cisgender and heterosexual because it prioritises the biological and the reproductive.

I kept my bisexuality a secret from myself until early adulthood. To recognise your sexuality as different from the one you assumed to be true is a sort of re-meeting of self. It sets you back a bit. It introduces a temporal messiness, overlap, glitch, see, I had a second first kiss.

The first woman I dated was younger than me. She said, This can never be serious. She said, Your queerness is brand new. You’re an infant.

Time is white and upper-middle class, too. It assumes linearity. That one will graduate high school and go to university. It assumes that one will get a job and buy a house. It assumes that one will having a savings account and a retirement plan.

T’s parents filed for bankruptcy and moved back into her grandmother’s place. Her little brother sold his company for tens of millions and bought a five-bedroom, six-bathroom, with a pool.