Joy and Rage: Why the Fight for Queer Equality Doesn’t End with Marriage

This Wednesday the Supreme Court overturned the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), so now we have to talk about it. DOMA was instated in 1996 under President Bill Clinton, and now 13 years later, it’s gone.

This, of course, has been a momentous week in American politics. The Supreme Court, being the showy queens that they are, save the best for last for each season that they’re in session, and this time around they made some decisions that will weigh on their legacy of human rights and change the immediate realities of millions across the country.

Human rights, of course, mean much more than gay rights, despite what the genius branding of the Human Rights Campaign would lead one to believe. Human rights are civil rights, a concept most strongly associated in America with the Black struggle for racial equality in the 1950s and 60s. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, which at the time was a landmark case that outlawed discriminatory practices that systematically prevented Black Americans from voting. Up until that point, this blockage from voting was one of many institutions that perpetuated the disenfranchisement of Black bodies and lives. Voting confirmed, at the very least, that they were participating citizens of this country, and that could not be taken away, no matter hostile the climate may still have been. The Supreme Court gutted this historic bill on Tuesday. DOMA was defeated on Wednesday.

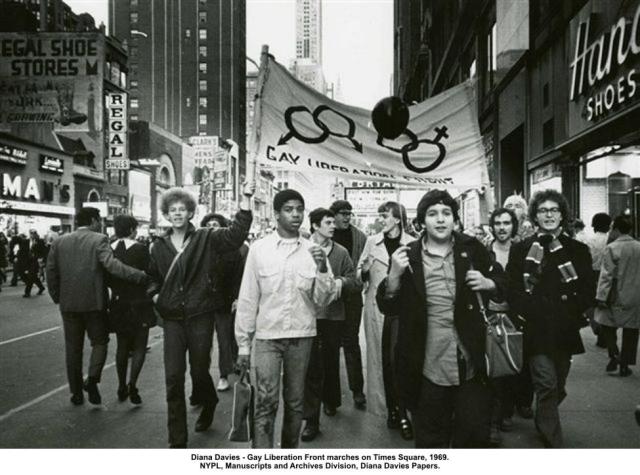

Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera know what’s up with intersectionality, marching for the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) at 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day March.

What does this have to do with gay rights? Well, nothing explicitly. The cruel juxtaposition of the two decisions is what’s most startling. We may call it progress when one historically oppressed group gains unprecedented rights, but what do we call it when another group simultaneously loses theirs after decades of brutal struggle? Furthermore, how do we begin to understand the total cognitive dissonance that begins to settle in when we realize that these groups are not mutually exclusive? There are now Black and Latino voters in “our community” who are not voters anymore. Their marriages may be recognized in the eyes of the state (if they are married under very specific circumstances), but suddenly their votes are not.

The idea seems to be to divide and conquer. Oppressed groups can’t gain true power in this country without each other. They may be placated with wins throughout history, but as we’ve just been shown, these wins can be taken back at any time, given the right context, political climate, and national culture that is taking place at any given historical moment. The act itself seems to be one of hypocrisy toward the idea of human or civil rights. Rights mean that we are entitled to them, that we are born with them, that we do not have to earn them, that they are irrevocable because they are our given fucking rights, and we have them because we’re human. At the very least, we have them because we’re citizens. Now we know that’s not the case, and we should keep that in mind before we get too distracted with this victory.

But can’t we just be happy for marriage for just one minute? Well, I think it’s fair to say that we have been, and I think it’s unfair to say that we can’t continue to be, even while remaining critical of the institution that enabled this freedom.

After all, it is the same institution that revoked it in the first place.

The frustration on all sides isn’t new. There’s this thing that happens on the left where you start a movement with huge blanket causes. It gains momentum and a large following, and with that large following, inevitably garners criticism. Your movement isn’t inclusive enough. Where are the people of color? Where are the queers? Where are the women? All too often, these questions are seen as “holding the movement back,” to which I say:

You’re damn fucking right. Because the struggles of queer and trans* people are no less important than the struggles of gay people, and if they move forward without us, they are not moving forward at all.

There are, of course very practical, very immediate, and very much deserved upsides to marriage. This is now especially true for binational couples, as laid out here by Immigration Equality. Married couples enjoy tax breaks, hospital visitation rights, and shared healthcare. Through marriage, individuals who are U.S. citizens could sponsor their partners for citizenship. It’s also worth noting that this is could be the second institutional channel recently opened to queer people. Under the Immigration and Nationality Act, members of the U.S. military also have a streamlined naturalization process, giving undocumented people – yes, even queers – the same opportunities to endanger their lives in exchange for access to basic human protections within this country’s borders.

For some people, this is more than just a theoretical argument or a symbolic stride, it’s a day-to-day reality. These are people’s lives. For some people, marriage matters. Increased access to resources matters. Being able to treat your partner as your partner – not just as a stranger – in the eyes of the law, that matters. And so celebrating a victory which might allow them greater access to those resources and rights is totally appropriate. But our power as citizens is what enables us to win these victories, and so by the same token, our celebrating should be done with the knowledge that many peoples’ power to effect more changes like this has been stripped away.

Is this indicative of a deeply flawed system in which couples may only gain access to healthcare, tax cuts, citizenship opportunities, and legitimacy of their own relationships through an institution supported by a government that refused to act on AIDS, that mandates policing of our bodies, that puts us under surveillance if we step out-of-bounds (or really even if we don’t), and that passed DOMA in 1996 “to reflect and honor… collective moral judgment and to express moral disapproval of homosexuality”? Well, yes. But that’s why the fight doesn’t end with marriage.

We won this past Wednesday. Well, at least some of us did. So celebrate, because you have the right to do that, and maybe now you have a future that you could have never imagined before. That’s something to celebrate. And then think about what it could mean to be an ally to those who may not have benefitted from this victory that changed your life. How can those living on the margins of the queer community expect to win their rights to dignity without the allyship of those who have greater privilege?

As Mia McKenzie of Black Girl Dangerous said yesterday in “Calling in a Queer Debt: On DOMA, the VRA, and The Perfect Opportunity”, this time is about action. She points out something that many people know but few people really, truly internalize – that you can be queer and something else. And that many, many of us are:

“Will you make room in your agenda for the rest of us? Those of us who are queer and black, trans* and Chicano, intersex and South Asian, and Two-Spirit? Will you speak up for us, while the cameras roll? Will you speak up for all the people in this country whose rights are being taken away while yours are being increased? Or will you be silent? It is not enough to acknowledge your privilege. Acknowledging it will never make it better, will never, ever change anything. At some point, you must act against it. This is that point.”

We are queer people. We have struggled with our desires. We’ve grown to fit our bodies. We’ve built communities. When society at large told us that we should feel hatred and shame towards ourselves, we found comfort in each other. We’ve defined love by our own means and standards. We’ve found a way. We create and struggle and feel. We survive. And we’re going to continue to survive, not just for ourselves but for our predecessors who died neglected by the government, who were beaten, arrested, and humiliated, for those who live and die on the streets, for those young people we’ve seen pass who felt that life as a queer person was unbearable in today’s world.

We just won marriage, but we won’t stop there because liberation means creating and living in a world that’s actually worth living in. We’re not going to stop at marriage, because we know now what we didn’t always know: we deserve so much more.