I love Buffy the Vampire Slayer and I love The Toast, so it’s no surprise that a thoughtful essay about the slayer published over there last week, “A New Version of You,” is currently my favorite bit of reading on the internet. I’d call it “light reading” but it’s not, really, though the tone is conversational and it’s certainly not a research thesis or anything like that (though if you’d like to read some serious academic texts about Buffy, that can be arranged). The subject matter is heavy, though, and it gets to the heart of why Buffy is still so meaningful and important to so many of us even though it has been off the air for over a decade. Kim O’Connor, the author of the essay, is talking about identity and expectations and reality versus cultural narrative, and being the introspective dyke that I am the whole thing forced me to take a walk down memory lane and remember how hard I was on myself when I first started coming out as queer, all because I couldn’t cut myself enough slack to realize a thing that O’Connor posits that Buffy as a show accepted all along: “…Despite the limitations of its 45-minute format, the characters juggled multiple versions of themselves all the time, constantly grappling with the contradictions, anxiety, and consequences surrounding who they had been, who they were, and who they would become in a surprisingly cogent way.” The idea of a person having multiple versions of themselves, sometimes all at once, is one of those brain nuggets that I give quite a bit of thought to every single day, so I was anxious to learn how I could situate my favorite teen girl badass into this line of thought. O’Connor did not disappoint, and I’m left with much to mull over.

O’Connor suggests that Buffy’s brilliance lies in the fact that “unlike most teen dramas, Buffy wasn’t a narrative about finding an identity; it was always about having a lot of them.” This speaks to me, as someone who never fit comfortably into any one of the high school stereotypes pop culture insists we must slot ourselves into from a very early age. I never had one group of friends in high school, and the people I did hang out with were not culled easily from after school activities or common interests. And while of course there were soccer players who mostly hung with the soccer team, theater kids who never left the confines of the auditorium, and smokers who seemed to never set foot outside the parking lot in the back, the truth is that most of my peers – even the jerks, even the insufferable ones – were similarly three dimensional human beings, not thin slices of personalities that fit easily into one tired trope or another. I’ve never thought about Buffy’s acceptance of this basic human truth, but O’Connor’s essay argues it clearly and convincingly, showing me yet another layer of the show that makes it so consistently enjoyable and so consistently heartbreaking at the same time. “As the show progressed, and the Scoobies coped variously with sordid pasts, spells gone wrong, and a horrifying spectrum of abusive boyfriends, its moral universe grew more complex. Identities and alliances shifted and relationships grew ever more muddled as evil—no longer relegated to the Big Bad in the basement—was embodied by familiar faces.” Never mind the fantastical (and sometimes spotty!) plot lines and the seemingly never-ending onslaught of apocalypses; Buffy and the gang were actually keeping shit really real.

Despite all that I knew about myself from my high school experiences – that it’s okay to not “fit in” with the dominant cultural narrative, that it’s hard to know yourself and it’s a project that needs a lifetime of upkeep and effort, and that you’re allowed to learn and grow and change your mind and your heart and even your brain and your soul as that growth occurs – figuring out that I was queer and that it was okay was really fucking hard. I just could not quite figure out how to navigate the new information I learned about myself and my sexuality when I fell for My First Girl. In some of the more obvious ways it was easy: Emily kissed me, I pined for her, I told my parents and we fought about it but it was mostly sort of okay. I was in London at the time Everything Happened, and then I was in New York after that, and it would be a lie to say my environment was anything other than accepting and educational. Coming out as a queer girl as a junior at New York University in 2009 is pretty much an ideal situation. And yet. I just kept encountering second guesses… pretty much exclusively from myself.

While my friends accepted my new feelings (mostly) easily, I tortured myself. I knew my feelings for girls were real – I felt them! – but how could I possibly be queer if I’d made it nineteen years on this earth without realizing it at all. Sure, I’d liked holding hands with my childhood friend Jess, and okay, I was a little unreasonably upset when Eliza acquired a boyfriend when we were 16, but surely that didn’t count as proof. At the end of the day, I had kissed and dated and fucked men for a long time, and I’d never considered that I might want to do those things with women too, or perhaps only with women exclusively, and so surely I had no business going around cloaking myself in this new queer identity. How could it possibly be real? If I hadn’t known it since I was small, was it a thing that could ever truly be mine?

Looking back I want to either punch myself in the face or give myself the tightest hug and the warmest mug of tea, but at the time I just struggled silently. I had grown up in this culture, the one that “place[s] a lot of emphasis on the coming-of-age story, as though it’s something that happens just once, early in life,” and I had drunk the Kool-Aid. Even as I felt feelings I knew to be true, and even as I intellectually knew that my identity was my own to define and redefine as often as need be, I couldn’t quite let myself be. O’Connor’s essay makes me feel like what I really needed was Buffy (duh), but unfortunately I wouldn’t discover The Slayer until a couple of years later. Had I seen the show earlier, perhaps I would have benefited from its core message. O’Connor writes:

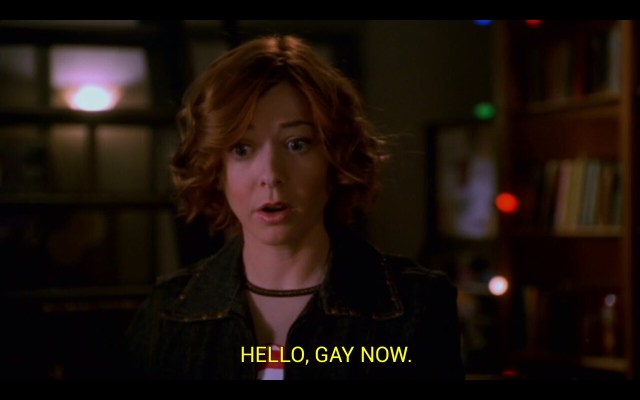

Life on the Hellmouth required a certain amount of flexibility. You might, for instance, spend 19 years of your life as an only child, only to one day find you have an annoying little sister that monks made out of mystical energy. At any given moment, you might turn into a rat, a demon, a werewolf, or a lesbian. In Sunnydale, no one was ever what they seemed, and by the time you’d figured someone out, they had already turned into someone else.

While I know it’s simplistic to say “you might turn into… a lesbian,” I think we can all agree that sometimes, for some people, it feels that way. It felt that way for me. And looking back on the unrelenting barrage of doubt I heaped upon myself, I really wish I had been watching BtVS when I came out to myself, because I think watching the show could have helped me. I think that is the point of O’Connor’s essay. Taking on the perspective the show holds about identity can help all of us. It was far more honest than any other teen dramas at the time (or since?), and frankly, it’s far more honest in its fictional narrative than most of us are with ourselves in real life.

O’Connor writes that Buffy’s “real artistic achievement was in its flat rejection of the notion we can ever come to know ourselves, much less someone else.” I love this, and I want to write it on a slip of paper and keep it close to my heart at all times. Now, four years after realizing I really (really, really) like girls, I finally feel safe in my body and my brain and the words I choose to define my own identity. I know that I’ll keep evolving, and I know that’s the way it’s supposed to be – how boring if we were all “done” at a certain point, if our identities tapered off and became static, if we “found ourselves” like we are so often told we should. I don’t want to find myself just once; I want to keep finding new pieces of me every day, and I want to remember that I am allowed to discover bits and pieces that I never saw before, and that those versions of myself are just as valid as any versions that came before, and any that might come next. O’Connor’s conclusion makes me certain that Buffy (and O’Connor herself) agree with these sentiments:

The thing is, Buffy was never about a girl coming of age. In her universe, as in ours, no one ever finds herself, at least not for long. With its relentless parade of Big Bads, demonic possessions, and fug leather pants, Buffy shows us how to face life’s central challenge: accepting the monsters we have all had to be, and those we have yet to become.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” column exists for individual queer ladies to tell their own personal stories and share compelling experiences. These personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.