What Happened in the Canadian Election? or, “Do You Still Want to Move Here?”

Stephen Harper has managed to form a majority government in Canada, which is pretty badass, unless you’re part of the 60.1% of the population who didn’t want the Conservatives to win. I am one of them, and I want to cry and have some vodka.

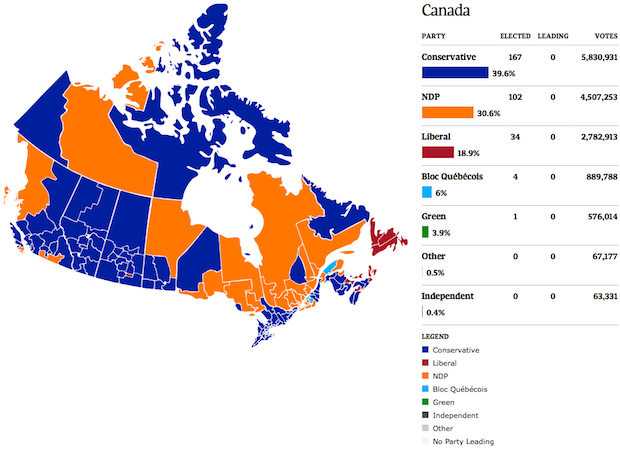

Final polls on Sunday evening suggested the Conservatives would form the government again, though a huge increase in NDP support made it hard to tell whether it’d be with a minority or a majority. And by the time the federal election was over, they won a majority, with the NDP as the official opposition, the Liberal Party reduced to a shadow of its former self, the Bloc Québécois in an even worse position, and the Green Party with its first Member of Parliment ever. Here is what this looks like:

Canadian Federal Election 2011 Results via the Globe and Mail

The Conservative Party received 39.6% of the popular vote, which translated to 167 seats in the House of Commons, thank you, first-past-the-post political systems (to form a majority government in this election, a party had to win at least 155 seats). This means that Harper has the majority government he’s always wanted. And the “popular vote” only includes registered voters who voted, and not people who didn’t vote or who had to be added to the registry that day. So 60% — and maybe more — of the population is unhappy with the way things turned out. And there isn’t much anyone can do about it. Instead, Harper has some things he wants to do, and now, he’s going to do them. You can’t fight the Harperbot.

Some of the things Harper is expected to try do include lowering corporate taxes while getting rid of the deficit (which, it should be noted, he created. When the Liberals formed the government in 1993, Paul Martin eliminated the federal deficit and paid down $36 billion in national debt, leaving Canada in a pretty good place, financially. And while spending during the recession was necessary, things like building a gigantic artificial lake were not); pushing a pro-business agenda; and completely ignoring climate change.

The New Democratic Party (NDP) received 30.6% of the popular vote, or 102 seats. This means they are now the official opposition, which is the first time this has happened ever, and which is really exciting.

However, because of the conservative government got a majority, the NDP actually have less power than they did before. Before, while they only had 37 seats, they could cooperate with the Liberal party, which had 76 seats, and the Conservative government had to cater to their every need. But now, while it’s awesome that the NDP are the opposition, they won’t have the seat power needed to actually oppose anything. They can yell about it, and gain experience in Parliament that their party hasn’t had, ever, and can be as annoying as they want during Question Period, but the chances of them being able to get things done isn’t good.

Additionally, the sudden rise in support for the NDP, particularly in Quebec, isn’t necessarily related to a seismic shift in the political spectrum. In an online debate in the Globe and Mail, André Pratte argued that while polls suggest 40% of the Quebec population might still be in favour of separatism and might elect the PQ in a provincial election, they are now more willing to take part in pan-Canadian public debate on issues that concern everyone:

“This presents the whole country with an opportunity to begin a new dialogue between ourselves, a dialogue that the Bloc domination had rendered difficult, if not impossible. That doesn’t mean Quebecers are less nationalist than before. But they have chosen to express who they are and their view of Canada through national parties rather than a separatist one.”

The Liberal Party received 18.9% of the popular vote, and 34 seats, down from 77 in 2008 (and that was under Stéphane Dion). Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff lost his seat in his home riding, and resigned as leader of the Liberal Party on Tuesday morning. While some are blaming the Conservative attack ads that featured Ignatieff as a “latte-sipping elitist, who returned from the hallowed halls of Harvard and London after a 30-year absence to take over the party and grab power for the sake of power,” while others have suggested that the Liberals shouldn’t have forced an election. It’s also been suggested that Ignatieff’s approach to the NDP was too divisive, and that rather than going on about “OMG! Scary socialists! Be afraid! Be VERY VERY AFRAID!” his energy would have been better spent trying to take down the Conservatives in any way possible. Whatever happened, the Liberal Party is a little bit like a Liberal Wake at the moment, as they wait to announce their third leadership convention of the past five years.

The Green Party received 3.9% of the popular vote, but also got their first seat ever. Elizabeth May, the Green Party leader who was excluded from the leaders’ debate, won her seat in Saanich-Gulf Islands, in British Columbia. While her riding has had a Conservative MP since 1997, the bulk of May’s support came from former Liberal supporters, and it was enough that she led significantly from the first poll results (her opponent, Conservative Gary Lunn, conceded the race after barely half of the results were in, and by the end she had nearly 48% of the vote. Across the country, though, support for the Green Party fell. In 2008, they received 6.8% of the popular vote across the country, but in 2011, they have only 3.9%. In the next election, they’re hoping to get up to eight seats.

The Bloc Québécois received 6% of the popular vote, which translated into four seats. Leader Gilles Duceppe lost in his home riding, and then resigned Monday evening. In a short speech at a rally in Montreal, Duceppe told supporters, “Those who supported the NDP wanted to give a last chance to a federalist party. Quebeckers now have the right to expect results, changes, a concrete recognition of the Québécois nation.” In 2004, the Bloc had 54 seats, which fell to 49 after the 2008 election. This time, a significant portion — by which I mean, almost all — of Bloc supporters seem to have shifted towards the NDP, particularly following the French language televised debate.

In addition to everything happening party-wise, there are a lot of other things to talk about in this election:

Voter turnout: According to estimates by Elections Canada, voter turnout was 61.4%, which was, embarrassingly, an improvement over 2008’s record low of 59.1%. The highest turnout Canada’s ever had was 79.4%, in the 1958 election that resulted in John Diefenbaker’s majority government. Even with an increase, 61.4% is still the third-lowest turnout in history, just above 2004 and 2008.

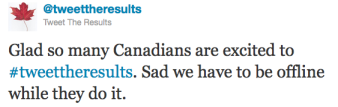

The Elections Act: The CBC may have broken the Elections Act by publishing the results from Eastern Canada in provinces that still had polls open. According to a representative for the CBC, the broadcast was due to a “switching error.” The Elections Act bans “premature transmission” of election results. Tweettheresults.ca did not end up breaking the Elections Act, though they meant to. The site, which was planning to display the results as leaked from polling stations and other sources, shut down at the last minute out of concern that, because of their sudden popularity, a complaint would be filed. #tweettheresults trended on Twitter anyway. Also, Stephen Harper broke election rules by campaigning by radio on election day.

Polls: The polling industry, which utterly failed to predict the way the Conservative supporters would translate into seats and a Conservative majority, has also been having a rough few days filled with existential self-doubt. Not only did the numbers during the campaign period vary wildly, which some have attributed to using different methods (phone interviews, automated phone interviews, or the Internet), they were also — with the exception of the results from Nanos Research — significantly different from what actually happened. The president of EKOS, one of the less accurate (this time) companies, told the Globe and Mail that the best way to fix something like this is to study the numbers and contact the people polled to see whether they voted the way they say they would, but that no one cares enough to actually (pay for them to) do it.

The youth vote: Rick Mercer-inspired Vote Mobs, which began at Guelph University, took over the world.

Inexperienced Members of Parliament: There are over 100 MPs who all have varying levels of political experience but who also have never been MPs before. Four of them are McGill students (three currently, one recently). This is incredible, and unbelievably cool, and also, a little worrying. People can applaud “fresh faces” and “new blood” all they want, but there’s a reason experience is valued, too. Whatever happens with this, the results will be interesting — just hopefully not in the way a car accident is.