UK LGBT Politics Crash Course: 2013 Was A Real Banner Year for Colonially-Influenced Homophobia in the Commonwealth

Despite significant strides being made in domestic UK politics, the Kaleidoscope Trust‘s annual report notes that the “year [was] marked by a series of serious challenges to the dignity, rights and freedoms of LGBT people around the world,” particularly in the Commonwealth. In this second of a three-part crash course on UK LGBT politics, we’ll consider the history of institutionalised homophobia and British colonialism, and whether the Commonwealth can or should do anything about it now.

What’s happened?

Of the 78 countries in which same-sex sexual behaviour is criminalised, 42 of them are in the Commonwealth of Nations, mostly made up of former territories of the British Empire. The anti-gay laws in these countries take different forms and are prosecuted to different extents – from being merely “symbolic” to carrying prison sentences – but are deeply rooted in a colonial past, with most laws specifically modelled after Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. (The UK only repealed its own sodomy law, under which Oscar Wilde was prosecuted and Alan Turing prosecuted and then recently pardoned, in 1967.)

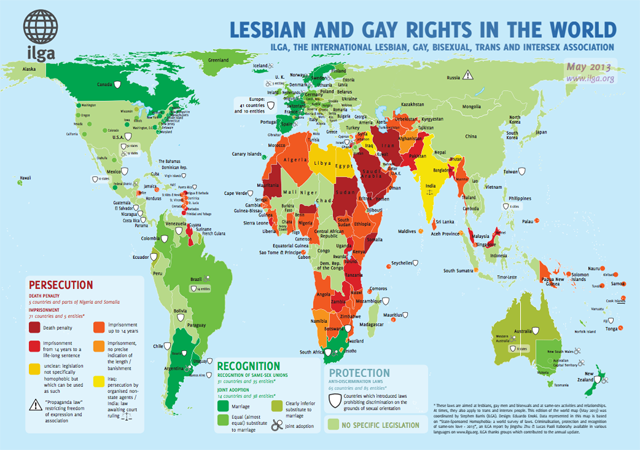

Summary map of LGBTI persecution, recognition and protection worldwide (as of May 2013)

via ILGA

While far from a comprehensive list, here are some key events that happened in the Commonwealth in 2013:

- Cameroon: As conservative groups have sought to increase already existing penalties for both male and female same-sex sexual activity, the country has seen an increase in anti-gay violence, notably the murder of activist Eric Ohena Lembebe.

- India: The Supreme Court struck down a 2009 Delhi High Court ruling decriminalising homosexual acts, upon which the government filed a review petition that is still pending. The Supreme Court is also currently reviewing if trans* and/or gender nonconforming citizens, particularly hijras who identify as neither male nor female, can be legally recognised as having a “third gender.”

- Nigeria: While sodomy is already illegal, the House of Representatives passed the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill 2011 to further criminalise same-sex relationships and LGBT activism. It is unclear whether President Goodluck Jonathan plans to sign it into law.

- Singapore: The Supreme Court struck down a challenge to Section 377A, which criminalises sex between men. A statement from the Attorney-General’s Chambers on the same case warned of an “incrementalist homosexual agenda” while a nation-wide survey revealed widespread hostility to “gay lifestyles.”

- South Africa: LGBT citizens and rights organisations mourned the passing of Nelson Mandela, still facing an uncertain future and dealing with “corrective rape” years after legal protections for LGBT people was enshrined in the country’s Constitution.

- Uganda: The Parliament passed the Anti-Homosexuality Bill 2009, popularly known as the “kill the gays” bill, which no longer imposes a death penalty but still calls for “imprisonment for life for the offense of aggravated homosexuality.” President Yoweri Museveni, however, “won’t be pressured” to sign (or repeal) the bill.

On a slightly different level, gay marriage was legalised in New Zealand while Australia‘s High Court said no to the same, passing the buck instead to the federal government to legislate on the issue.

Anti-Section 377 protest in India

via Think Progress

According to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in their 2013 report Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change, “in recent years many states have seen the emergence of new sexual nationalisms, leading to increased enforcement of colonial sodomy laws against men, new criminalisations of sex between women and discrimination against transgender people.”

The Queen maybe kinda sorta cares about the gays and David Cameron wants to “export” gay marriage around the world. However, despite lobbying by activists and a promise from Downing Street to raise the issue, any discussion of LGBT rights was conspicuously absent from the agenda for the 2013 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting held in Sri Lanka.

What’s coming up next?

The UK government has not demonstrated a consistent policy position on LGBT rights abroad, whether in the Commonwealth or elsewhere, but this shouldn’t come as a surprise – foreign policy always centres national interests. For instance, threatening to cut bilateral aid, as Cameron did to countries like Ghana and Uganda as anti-gay laws gained traction in 2011, not only shaves millions of pounds off the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)’s budget but leaves the UK emerging as morally superior to boot.

So what the UK does in 2014 (or whenever) will be guided by what’s best for the UK, not a kumbayah global community. In this economic climate, this might simply mean more sanctions in the name of human rights.

People protesting against the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting

via Demotix

Commonwealth scholar Frederick Cowell is mostly pessimistic about the potential for LGBT-related human rights advocacy, noting that “the states actively opposing the decriminalisation of laws criminalising same-sex sexual conduct are the numerical majority in the Commonwealth” and that the authority of the international organisation is necessarily restricted by its voluntary nature and colonial past. Other scholars, however, are working to identify effective, replicable strategies across the Commonwealth nations or taking more in-depth country-to-country approaches to distill what can and should be done. It is overall a positive sign that human rights in the Commonwealth is an emerging area of scholarship and activism.

What’s at stake?

The Commonwealth is a tricky entity. Some see it as a crucial body through which states’ sovereignties are recognised and realised, both in securing independence from European colonial masters and through the aid/trade opportunities facilitated by membership. Others see a rather unabashed institution of neocolonialism – that is, the replacement of formal empire occupying lands and peoples through force and bureaucracy with a “softer” power expressed through economic and cultural hegemonies.

Commonwealth flags

via Shutterstock

The Gambia, one country which was facing increasing pressure from the UK to stop restricting the rights of its LGBT population, left the Commonwealth in 2013 citing exactly this:

“The government has withdrawn its membership of the British Commonwealth and decided that the Gambia will never be a member of any neo-colonial institution and will never be a party to any institution that represents an extension of colonialism.”

– Gambia President Yahya Jammeh

What’s particularly contentious here is that the Commonwealth holds its members to a shared (albeit notional) standard of “human rights.” South Africa was banned from 1961 to 1994 during the period of Apartheid, while Fiji’s membership is still suspended due to a “lack of progress towards democracy.” International activists have agitated to have LGBT rights more explicitly recognised as part of this conception of human rights – no country has ever been suspended for state homophobia – but more fundamentally, we need to ask: whose “human rights” are these? Who gets to decide, and who enforces them?

In theory, what Commonwealth nations have in common is mutual respect for each other and this code of human rights. In reality, what Commonwealth nations have in common is British colonialism. The UK still dominates the political and moral leadership of the Commonwealth, and in particular, Cameron wants the UK to be a “global beacon for reform” on LGBT rights. There is a special kind of irony in taking the cue on “human rights” from a leadership that not too long ago considered most of the population of the Commonwealth to be literally sub-human. That irony deepens when the same power that now wants to “save the gays” was historically responsible for much of the institutionalised discrimination that LGBT people in the Commonwealth face in the first place. Thus, tasking UK leadership in the Commonwealth with promoting LGBT rights is not only hypocritical but risks “pinkwashing” the harm that has been caused by colonialism, using queer causes and bodies as justification for continued imperialist rhetoric and actions.

It is, of course, more complex than that. There are different reasons for why anti-gay sentiment has swelled, to different extents and in different forms, in Commonwealth countries: some political (see the prosecution of Anwar Ibrahim in Malaysia), some religious (gays and lesbians as “against Christianity” in Uganda or “anti-Allah” in the Gambia), and some nationalistic or cultural (homosexuality as “un-African”). Neither is the UK the only imperialist power implicated in these struggles: US evangelicals are backing some of the most vicious laws in Uganda and elsewhere.

David Kato, a Ugandan activist murdered for his LGBT activism

via CNN

From both a foreign policy and activist perspective, international intervention can go horribly wrong. We see this pattern over and over again, from KONY to V-Day to FEMEN: white saviours descend upon faraway communities with crowd-sourced funds and catchy slogans, backed by governments wielding economic sanctions and “name and shame” tactics in international diplomacy. International groups too often pay little heed to what local people want or need in the name of saving brown people from their oppressive brown leaders and backward practices – in the process overriding or undermining the efforts of local activists and leaving them to deal with the backlash. LGBT human rights activists in the Commonwealth are constantly attacked for importing “Western” behaviours and inviting unwelcome interference, which will only intensify as international interest picks up.

There is a grain of truth in accusations that LGBT issues are “Western.” Colonial legacies did not only impart anti-gay legislation but disrupted native communities, kinship networks and cultural identities and practices in order to impose colonialists’ standards of “civility” and more neatly incorporate dominated populations into their capitalist projects. It is not only homophobia that was exported but specific – and now dominant – understandings of gender and sexual identity, such as the “born this way” narrative, sexuality as identity instead of behaviour, and binary, biology-dependent conceptions of gender. Some communities have embraced these ideas and politics, while others haven’t, which is something to always be conscious of – any activism that seeks to impose monolithic narratives of the queer experience and struggle, prioritising a “global LGBT community” over local nuances and sensitivities, is in itself part of the problem.

Anti-gay protesters frequently conflate LGBT movements with Western imperialism

via The Atlantic

What can the UK and the Commonwealth do, then? A recognition of its complicity in anti-LGBT discrimination and violence would be a start. Would an apology from Cameron, as some have been calling for, do any real good? Probably not. It gets even trickier when you try to conceive of what form this “apology” would take, and whether it’d really be able to capture the complexities of past and present LGBT rights struggles in the Commonwealth. But if the UK wants to be a “global beacon for reform” in any of this, leading the way in bettering the lives of LGBT people at home and abroad, these are fundamental issues that need to be considered – and I won’t be holding my breath waiting for the current government to.

There is no easily generalisable way to map the terrain for LGBT activists and people in each Commonwealth country, and no clear indication of where we go from here. As setbacks in India, Uganda and elsewhere showed us in 2013, it is too easy to fall into the trap of thinking that LGBT rights and recognition are an inevitable reality. We don’t get to just choose which side of history to be on – we need to actually be making that history happen, and it’s likely to be a long, difficult path ahead.

Stay tuned for the next installment of this mini-series on UK LGBT politics!

Feature image via YEMMYnisting / Free Thought Blogs