Transgender People, Transitioning and Those Darn Standards of Care

Before I sought gender transition, I had never heard of the Standards of Care (SOC), so I’m going to guess that most of you are in the same boat I was in. The SOC is a very important document in the trans world and in the field of trans healthcare. They are nonbinding (aka not mandated) protocols from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) outlining how clinicians in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, medicine (both primary care and endocrinologists, aka hormones), and surgery should best treat transgender patients.

They’ve been around since 1979 and doctors who have been “progressive” enough to work with trans patients have largely adopted the SOC as a rigid policy guideline. A lot has changed in terms of the view of trans people, their needs, et cetera, in the past 30 years, so as you can imagine, there have been a number of revisions. However, until the 7th version was released this week (more on that later), the last revision (Version 6) was in 2001. Yikes! I know.

It was definitely outdated, and had a real love/hate relationship with the trans community.

Standards of Care, Version 6

The use of this screencap will make sense in two seconds

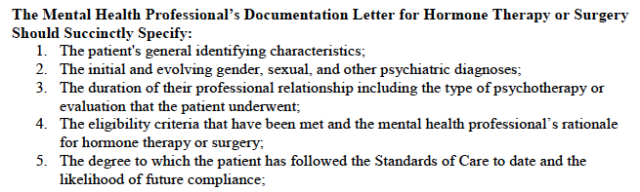

For starters, the title was The Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders. It literally positioned counselors, psychologists, doctors, and surgeons as “gatekeepers.” It required a certain amount of psychotherapy and/or full-time living in your desired gender role before you could undergo hormone therapy. Patients’ “eligibility” for medical interventions (hormones or surgery) was “assessed” by their clinicians based on whether they met required criteria.

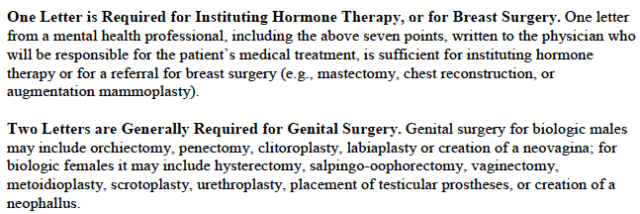

Excerpt from The Standards of Care, Version 6

Excerpt from The Standards of Care, Version 6

The entire document centered around the concept of “transsexualism” as a mental health diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder and very much contributed to the general patholigization of gender variance in the medical and mental health fields. It used outdated language and in general just didn’t make this trans guy feel too warm and fuzzy about himself upon reading it.

Excerpt from The Standards of Care, Version 6

BUT, on the bright side, the SOC did say that some trans people need hormones and need surgery and have the right to access these interventions (or at least to access people who get to decide if we can access it). It also served as a helpful tool when it came to dealing with the few insurance companies that were somewhat willing to cover gender transition-related interventions. And you know, at least it included this disclaimer sentence:

“The designation of gender identity disorders as mental disorders is not a license for stigmatization, or for the deprivation of gender patients’ civil rights. The use of a formal diagnosis is often important in offering relief, providing health insurance coverage, and guiding research to provide more effective future treatments.”

So that’s the little bit of love it got from the community right there. Yes, it sucked, but at least it justified our needs as medically necessary and gave us some validation and legitimacy to the outside/medical worlds. What was it actually like to live with? Well:

Our Experience With the Standards of Care

Sebastian:

Because there is SO LITTLE out there about transgender mental and medical health care, I feel like doctors and therapists who encounter trans patients for the first time (and even those who have seen multiple trans patients) look at the SOC as the Bible of trans healthcare. And as a result, I think there is no denying that we’ve seen a large amount of the people treating trans patients really mismanaging their patients and clients’ care, because the SOC was outdated and provided actual honest-to-god misinformation. I’ve already mentioned that it really pathologized gender variance. In addition, it stuck to really old definitions of transsexualism and what trans people look like and need. I’ve heard countless reports of trans men whose therapists wouldn’t approve them for hormone therapy because they weren’t masculine enough. Or trans women who couldn’t move forward because they were attracted to women. And genderqueer people who wanted some medical interventions? Forget it – nearly impossible. Because yes, in most cases endocrinologists (our hormone docs) require written APPROVAL from our therapists before we can move forward. Therapists who only sought out the SOC and the diagnostic criteria of “Gender Identity Disorder” as a source of education on trans people have been the gatekeepers to our medical transitions.

My mom is a psychotherapist, so when I came out (and finally started being pushy about it), she contacted a queer colleague who guided us to a true expert. I was lucky and saw a psychologist who was trained in gender variance psychology, who trained on it even! I knew I was a lucky one when she told me about one of her patients who had transitioned to male and now performs as a drag queen. I knew that unlike many other trans and genderqueer people, I would not be spending my therapy time (and MONEY) trying to prove my transness, my masculinity. She explained that she saw her role as assessing my psychological state (separate from my gender identity, which she did not label as a disorder – except on the required insurance forms and the required letter for my surgeon) to make sure that I was stable enough to handle what transition meant. In session we explored the caveats of my identity and I was able to work out (for myself) what kind of transition I needed. She, as the expert, provided me with the realities (positive and negative) of each step of transition and of the options of not transitioning. And she worked with my family to help them understand what I was going through and to help them with all the struggles that come with being SOFFA (Significant Other, Friend, Family, or Ally) to a transgender person. That was her role – not a gatekeeper. She did not follow the Standards of Care “recommended” (I put it in quotes because it’s really written more as an official rule book) length of time in therapy.

I also saw a second therapist, because for a time I was living in Massachusetts and my other therapist was in North Carolina. I told my Massachusetts therapist on the phone that I’d been in intensive gender-related therapy for a month a few months back, that I’d been living as a man (to the best of my ability without medical intervention) for 6 months, and was coming to see her with the main goal of getting approval to start testosterone. I had two sessions with her. She believed in the informed consent model that is practiced in a handful of clinics specializing in gender transition. That is, she also rejected the notion that she was a gatekeeper. She believed I was an adult and that the decision to transition was ultimately mine not hers. She worked closely with a Nurse Practitioner in the region who has extensive training in transgender medical health care and prescribes hormone therapy as well as serves as the primary care doctor for transgender patients. My Massachusetts therapist called this NP, told her that I’d been in to see her, and was ready for the next step. I made an appointment with the NP, in which she explained all the effects and risks of hormone therapy and had me sign an Informed Consent waiver of sorts. Then I had my bloodwork done, got the green light, made a second appointment, and got my prescription (one of the happiest days of my life)!

In order to have top surgery, the surgeon’s office did follow the SOC and required a letter from a therapist in order to perform my double mastectomy. At that point, I had been on testosterone for a couple months, had been living as a man for 9, and had two therapists’ stamps of approval (in the event that they were asked), so I could produce a letter easily. My insurance company (which didn’t cover anything by the way, but did ultimately allow my parents to use our Flexible Spending Account to pay for the surgery) required a letter from psychologist holding a Ph.D – not only did they want a gatekeeper’s approval, that gatekeeper had to know their shit to be sure I wasn’t you know duping them for a medically-unnecessary just-for-kicks 2 hour invasive and pretty permanent surgery.

I was lucky. I live in a generally queer-friendly and queer-informed area. I’ve got connections because of my socioeconomic level and my parents’ professions. I had transportation to the doctor (who, although relatively close, was in a city 25 minutes away). And I had mental and medical health professionals who actually knew what the fuck they were doing and used the SOC as a tool and not a rule book.

If it hasn’t been made clear, I’m not down with the 6th version of the SOC.

I’ll just briefly address my issues with the old SOC. So there’s the issue of working with this as disorder, a condition – boo. There’s the use of outdated terminology and the misinformation about prevalence, presentation, et cetera – boo. There’s the complete lack of support/guidelines for genderqueer or even gender nonconforming (i.e. a feminine or gay trans man) people – boo.

Let’s talk about the therapy bit. Not only do I, as discussed earlier, have an issue with placing therapists as gatekeepers when many are seriously uninformed and providing them with a document that is supposed to be the final word but actually is woefully inaccurate, I also think that placing them in this role prevents people from actually benefitting from therapy. Therapy isn’t necessary for everyone who seeks medical transition, but for most of us there’s a lot of shit that comes with being trans, comes with living before, during and after transition. And I think most of us could really use professional help in dealing with that. But we can’t establish a therapeutic relationship with any clinician if we’re focusing on proving to them we’re trans enough or masculine enough or “straight” enough et cetera et cetera.

Also, this is a class issue. Seeing a therapist regularly (some gender therapists require weekly sessions) for 3-6 months is expensive. Even if you have health insurance that covers it, the copay adds up. If you don’t have health insurance or the expert in your area isn’t covered? We’re talking thousands of dollars. For therapy that isn’t even necessarily therapeutic — but is required to move forward.

Now, the SOC did offer an alternative. For doctors that would accept it (many still absolutely won’t move forward with anything without a therapist letter), Version 6 of the SOC says that a certain amount of time lived consistently (aka full-time) in your desired gender role could make someone eligible for hormone therapy. At this point I just get mad. It is difficult and often dangerous to live as a different gender without medical intervention. Before testosterone, I was misgendered (read as a girl) 90% of the time in Northampton (where there are lesbians everywhere). In North Carolina, I was misgendered about 40% of the time pre-T. For trans women, this reality is even harsher. When I didn’t “pass” people thought I was a lesbian. A trans woman that doesn’t “pass” is clearly transgender or possibly read as a transvestite. It is very, very hard for a trans person to be read as their true gender without some medical intervention. And for a great number of people, being perceived and recognized as having a non-conforming gender identity is extremely dangerous, sometimes life-threatening.

The final thing I’ll mention is that for children and adolescents especially, Version 6 of the SOC provides a very singular and stereotypical image/definition of “transsexualism.” It has not been helpful at all in dealing with the increasing amount of children and their families seeking transgender counseling and transition options.

So that’s my beef. And I think that my therapists and doctor provided a very healthy and well-informed alternative to the hoops and bullshit of Version 6 of the SOC — I know it can be done, and now you do too.

Annika:

I didn’t know very much about the Standards of Care until recently. I came across the term in high school during the times that I would research trans* issues when nobody was looking, but I didn’t pay very close attention to the details since at that point in my life transitioning seemed like an impossible fantasy. It wasn’t until January of this year that I began to truly understand the requirements and implications of the SOC. I remember receiving a phone call from a friend, after I told her that I hoped to start HRT as soon as possible, preferably in a matter of weeks. “You know you won’t be able to begin taking hormones until April at the earliest, right? I read that you need three months of counseling first, and the therapist will have to write a letter approving you before any doctor will write you a prescription.”

This was devastating news. The experience of coming out had been so emotionally draining, and now that I was no longer afraid to be myself, I needed to start HRT. It’s almost as if coming out flipped a switch in my mind where I could no longer keep the dysphoria bottled up inside. My discomfort with my own body was increasing by the day. I wanted to cry every time that a stranger addressed me as “sir.” The prospect of having to wait several months before alleviating this pain was really distressing. To be honest, I don’t think that I could have done it. Out of desperation, I placed an order for hormones from an online pharmacy. I was well aware of the risks of self-medication, but it seemed better than the alternative: suffering through months of therapy trying to convince some psychiatrist that my gender identity is real. Thankfully, my girlfriend stopped me before I could take the first pill. We decided to look for other options.

I discovered that there were a number of doctors and clinics in San Francisco that did not follow the rigid SOC protocols, but instead provided trans* healthcare under a system called “informed consent.” This meant that following an initial psychiatric evaluation and necessary medical tests, a patient will be given hormone therapy as long as they understand and consent to its effects. I excitedly scheduled my first appointment at Lyon-Martin, a health clinic that primarily serves women and trans* people, only to learn a week later that my appointment had been cancelled and the clinic would be shutting down (most informed consent clinics are severely underfunded, but luckily Lyon-Martin managed to survive.) I then decided to go to Dimensions, a public health clinic that specializes in serving trans* and queer youth ages 12-25.

In the two weeks before my Dimensions appointment, I had a lot of time to reflect on the inherent flaws of the SOC. The therapy requirement seemed prohibitive to those who can’t afford to pay for multiple sessions with a counselor trained in assisting trans* people. The “documented real life experience” before allowing a patient to start HRT was at best absurd and at worst downright dangerous. The narrow definitions of “masculine” and “feminine” behavior excluded everyone who doesn’t have a binary, normative identity. I was turned off by the classification of my being trans as a “disorder”, and the entire document seemed designed to discourage people from pursuing transition.

My parents and I were still on speaking terms at this point, and I wrote an email telling them of my plan to start HRT at Dimensions. This did not go over well with them. Apparently they had spoken with my childhood pediatrician, who told them about the SOC, and warned that I was making a big mistake by not following them. To no avail, I tried to explain to my parents that I didn’t need my pediatrician’s approval, and why the informed consent option was a better choice for me. I think that the “gatekeeper” model of the SOC gave them hope that I might not actually be trans until a therapist confirmed it. When it became clear that they couldn’t persuade me not to start hormones, they cut off all contact with me.

I was so nervous and excited when the day of my Dimension appointment finally rolled around. The first thing I noticed when I arrived at the center was how many of the other patients were homeless. I was instantly struck by how privileged I am, and just how important informed consent clinics are for marginalized communities that have nowhere else to turn. After checking in, a nurse called me into a room and asked me a few questions, including about my sexual orientation. When I told her that I was a lesbian, she gave me a huge, affirming smile. I knew that I had made the right choice by coming to Dimensions. After discussing what to expect from HRT, I signed a form agreeing to the treatment. A week later, I picked up my first prescription at the local pharmacy. Looking back, I can’t tell you how happy I am that I decided to forgo the bureaucracy and injustice of the old SOC for my transition.

Annika's Informed Consent

The New SOC

Sebastian:

Both Annika and I benefitted from having clinicians and resources that worked outside of the old SOC. Through our various processes of medical transition we both came to understand the shortfalls of these rigid “guidelines” and, though I cannot speak for Annika, I occasionally groaned about their outdatedness. I did little to change it, though. For some reason, I thought they were here to stay for a while. Perhaps I had internalized some of the pathologization and saw WPATH as my governing body, as an institution that had the right to govern my body and others. I am currently in the process of applying to Counseling Psychology PhD programs and my big push in my personal statement and desired research directions is that we have no research on effective counseling and psychological “treatment” of people suffering from gender dysphoria, no accepted standards of therapy, and very little professional training in the area, yet we mandate that therapy be a process before these people can transition!

The bad news is that I’m going to have to rewrite parts of my personal statement. The good news is that last week the SOC got a pretty major overhaul from WPATH. A lot of the things Annika and I wrote about above have been removed from the guidelines. Therapy is no longer a requirement, nor is a set period of living “full-time” in your desired gender role. The name itself has been changed to rid the document of the term “Gender Identity Disorder” and to include nonbinary (i.e. genderqueer identities). It is now “The Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People.” The thought behind the title change is clear throughout the document. The introduction includes a clear move away from pathologization, writing explicitly about the differences between gender nonconformity and gender dypshoria, and about the differences between gender dysphoria and an unnamed mental disorder (*cough* Gender Identity Disorder). This is my favorite quote:

“A disorder is a description of something with which a person might struggle, not a description of the person or the person’s identity. Thus, transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming individuals are not inherently disordered. Rather, the distress of gender dysphoria, when present, is the concern that might be diagnosable and for which various treatment options are available. The existence of a diagnosis for such dysphoria often facilitates access to health care and can guide further research into effective treatments.”

Instead of lists of eligibility requirements, and a very linear chronological path of medical transition, the SOC addresses “options for psychological and mental treatment of gender dysphoria.”

Instead of setting up the therapist as a gatekeeper to whom the patient has the responsibility of proving herself, the new SOC list roles and responsibilities of the mental health workers themselves. These new guidelines list one of the tasks of therapists as referral to doctors who can provide medical intervention, rather than approval for such procedures.

Now in order to receive this referral (which does not require a set amount of therapy sessions and in fact can just be the result of a one-time psychological assessment), criteria still need to be met, the main two being “persistent gender dysphoria” and “capacity to make an informed decision.” Is it becoming clear how many lightyears beyond the last version the new SOC is?

Medical students at the 2011 Trans March in San Francisco (via Berkeley: In the World)

It still has its shortcomings and there is a lot more to discuss, but I think there are other forums for this. As people who have had first hand experience with some of the pitfalls, hurdles, and triumphs of trans health care, we just wanted to take the opportunity (thanks Editors!) to showcase some of these to a non-trans audience who understandably probably have no idea what this business of transition entails in terms of the health care system. An important message to take from this is that times they are a changin’. I think it will be a slow, years-long process for mental, medical, and surgical health care providers to shift away from the old SOC and adopt the better policies of version 7, but at least the, you know, experts are moving forward.

Oh, and also the DSM

We’d be remiss if we made it all the way through an article on trans health care and didn’t mention the proposed changes to the American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In a big push (from activists, advocates, doctors, professionals, etc.!) away from the pathologized “Gender Identity Disorder” the new version of the DSM (whose release date keeps getting pushed back) is likely to drop GID from its list of disorders. The proposed revision is to replace this diagnosis with Gender Dysphoria (and to clearly separate the diagnoses of gender dysphoria in adults and gender dysphoria in children and adolescents). The diagnostic criteria have been revised as well. You can see the old criteria and the proposed revisions at the DSM-V development webiste.

Read more about the changes to the Standards of Care at the Bilerico Project.