Thirsty Classics is a nine-week miniseries celebrating lesbian cinema from before 1980. We often talk about these films like homework or mere stepping stones, but Drew is here to share how they can be fun… if you’re horny enough. This week: Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform starring Dorothea Wieck and Hertha Thiele.

When my Hebrew school showed us Schindler’s List they skipped past the sex scene so we wouldn’t see nipples.

The decision to show this film at all, with its goy protagonist, horrifying violence, and maudlin Jewish characters, was proof that the Nazis had won.

I’d already seen the film and was not impressed. Like many closeted Jews/future theatre kids, my favorite Holocaust movie with a goy protagonist was Cabaret. Unlike Spielberg’s stodgy self-serious trauma porn, Cabaret was a celebration. This is what we had. This is what we lost. It emphasized that the Nazis didn’t just murder people. They murdered ideas. They murdered freedom.

But, as we know, their victory was not complete.

Pre-WW II German film is filled with a queerness and sexuality that reflects the culture of the Weimar Republic. Ernst Lubitsch’s early silent film I Don’t Want to be a Man (1918) was all about a “woman” dressing as a man and flirting her way across town. Richard Oswald’s Different from Others (1919) was explicitly about a gay male romance and was co-written by Magnus Hirschfeld, a prominent queer advocate and pioneer of transgender medicine. And then, of course, there was Marlene Dietrich.

As this era approached its tragic end, one last remarkable work of queer cinema was produced. Less than two years before Hitler was sworn in as chancellor, and one year after the setting of Cabaret, we were given the first film to ever explicitly be about queer women.

Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform is not only the first lesbian film. It also completely shaped the culture around lesbian cinema. So many of the things we now call tropes, began with this horny masterpiece.

After an opening montage of homoerotic sculptures and boarding school girls marching like soldiers, we meet Manuela, our protagonist. Manuela is fourteen (fourteen and a half, she clarifies) and new to the school. Her mother has died and her aunt has grown tired of the girl she describes as “overly sensitive and a bit of a scatterbrain.”

She meets the other girls and is immediately informed how lucky she is to be in Fräulein von Bernburg’s dorm. “All the girls have a crush on Fräulein von Bernburg,” says Ilse, the troublemaker of the bunch. “One minute she looks at you terribly. Then, all of a sudden, she’s very kind,” she continues, describing most of my crushes between the ages of 4 and 25, my current age.

As Ilse says this to Manuela she leans in close, flirting by proxy. Manuela tries to ignore this information, but Ilse continues, finding any excuse she can to touch her. She’s bursting with confidence, humor, and all-consuming adolescent horniness.

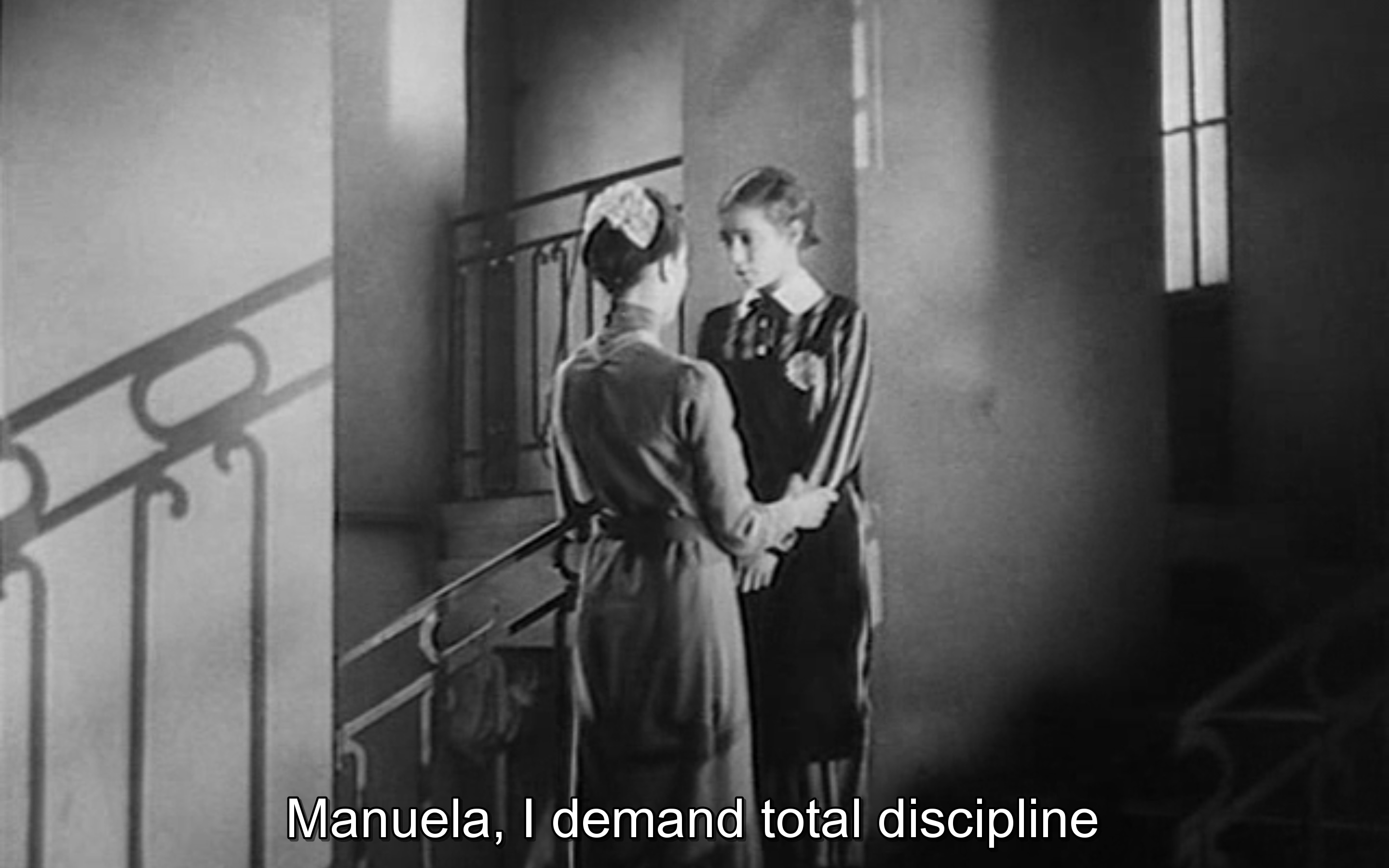

And then we meet Fräulein von Bernburg. Manuela runs into her in the hall and von Bernburg grabs her wrists. She tells Manuela that she must be obedient. Her word choice and tone sound less like a concerned teacher and more like a BDSM scene.

Manuela is played by Hertha Thiele who was 23 at the time of shooting. Ellen Schwanneke who played Ilse was 25. Some of the other girls were played by actual teenagers, but most were not. The suggestion that these grown women are fourteen implies this is what teenagers look like. And since the film overtly sexualizes them, and wants us to do the same, this suggestion is dangerous. Even though no relationships are ever consummated, it’s worth pausing to acknowledge this entire premise is less than ideal. Especially because it’s so influential.

Like many adult queers, I love coming-of-age movies because they provide an upbringing I never had. I didn’t come out until I was 23, so my lesbian adolescence was confined to make outs with other closeted queers. It’s unsurprising that watching queer teenagers fall in love and actually get to be in love warms my heart.

But when it comes to sexuality, where’s the line between wish fulfillment and lusting after teenagers? Are these movies simply role play? Does it matter how the characters are presented and their relationships are framed?

While a film like Jacqueline Audry’s Olivia directly engages with the reality of a student/teacher relationship, Mädchen in Uniform leans deep into the fantasy. If you can’t get past this, I understand, but I think one of the reasons the film still works is because of how deeply we’re placed within Manuela’s gaze. She is not a sexual object. She’s a sexual being. And most of her sexuality is directed at Fräulein von Bernburg.

Ilse excitedly informs Manuela that every night Fräulein von Bernburg kisses each of the girls goodnight. A peck on the forehead. Or, as Ilse puts it, “Gives each one a smacker! Wonderful.”

While she makes her way across the room, Ilse sits up perched and ready to go. Manuela is slightly more reserved. But when it’s finally her turn Manuela wraps her arms tightly around her teacher. Von Bernburg pulls her arms down, places her own hands on Manuela’s face, and kisses her softly on the lips.

Manuela falls back to bed with a grin so wide it’s falling off her face. I doubt she got much sleep that night. And I definitely know what she dreamed about.

The girls love Fräulein von Bernburg because she’s sometimes mean and sometimes nice and always hot, and, yes, kisses them every night. But the real reason they love her is because she’s tender in an environment that’s harsh.

During a staff meeting, von Bernburg says that she tries to be a friend to the students. The other teachers scold her for emotionalism. The rest of the staff is not only cruel in their words. The girls are also underfed, overworked, and unable to even own books. The headmistress says that the girls are daughters of soldiers, the future mothers of soldiers, and so they shouldn’t need… food.

That last declaration is shown in contrast with the girls, alone, fantasizing about what they most want to consume. One girl says coffee cake with a thick top. Another says an éclair, as she sensually describes the cream. These are girls who desire. They’re teenagers and they have big wants and big needs. They constantly have their hands on each other and they even write love notes back and forth. Von Bernburg intercepts one of these notes and destroys it without comment or punishment. She understands their feelings are normal.

Madchen in Uniform is ultimately about oppression. The oppression of sexuality, of all forms of pleasure. The headmistress has created a school run on fascism and Fräulein von Bernburg has dared to suggest there’s another way.

The lines between understanding teacher and grown woman in love with her student continue to blur as Manuela’s crush becomes more explicit.

Von Bernburg finds out that Manuela cries herself to sleep every night and she calls her in for a chat. She asks her if she’s homesick.

“Homesick?” Manuela replies. “No. I just feel like crying sometimes.” If that’s not a big gay mood I don’t know what is.

Von Bernburg continues to push. When Manuela says that her feelings are too hard to explain, von Bernburg says, “Well, try. I’d really like to know.” She’s so warm in these moments. When placed in contrast with the rest of the school it’s overwhelming. She’s every parent, every mentor, every sexual fantasy. She makes you feel like everything just might be okay.

Manuela opens up.

“When you say goodnight and leave, and shut the door to your room, I stare at the door in the darkness. I want to get up and come to you, but I know that I can’t. And I think when I get older and have to leave the school and every night you will kiss other girls.”

“What thoughts you have,” von Bernburg says trying to minimize this declaration. But Manuela is ready with an even clearer one. “I love you so much!” she shouts frantically.

The gay feelings finally become too much for Manuela when she stars in the school production of Schiller’s Don Carlos. Yes, she is both “dressed as a man” and wearing tights. Yes, she has multiple romantic scenes with another girl.

Afterwards, Ilse comes up to Manuela praising her performance. They lean their faces close together. It’s obvious they should let go of their teacher and crush on each other instead. But they’re not ready for that reality. So Ilse says that von Bernburg was watching closely the whole time.

Manuela finds her teacher and she confirms this to be true. She tells Manuela that she could be a great actress if she wanted to be. These two scenes confirm that Manuela’s crush is more than misguided. She’s so much more comfortable and real with Ilse. But who among us crushed on the right person as a teen.

Soon this will all explode.

The girls are given celebratory punch at the after party and Manuela drinks more than her fill. Before she or anyone else knows it, she’s standing in front of everyone declaring her love for Fräulein von Bernburg. The headmistress hears and confronts her. But Manuela commits. “Yes everyone should know!” she shouts before passing out.

After this episode, the headmistress bans Manuela from seeing von Bernburg. Knowing the alternative is expulsion, the teacher tries to comply. She tells Manuela, “You must be cured whatever it takes.” Manuela looks at her with pained longing. “Cured? Of what?”

Like so many works of lesbian cinema, Mädchen ends in suicide. Unlike so many works of lesbian cinema that suicide is not successful. The film spares Manuela that fate and spares itself an easy dramatic choice. Instead Manuela is pulled off the ledge by her peers and they all confront the headmistress with their stares. In solidarity, they side with Manuela, they side with Fräulein von Bernburg. They declare that this school is a safe place to be a gay. They declare that this school is a safe place to have feelings.

Mädchen in Uniform cannot be separated from when it was made. It’s an explicitly anti-fascist work made in a time when fascism seemed inevitable. It was made in a place where queerness was accepted, but on the brink of being erased.

Yes, this movie was the first (that we know). Yes, with its boarding school setting, its central age difference, and its near-suicide ending the movie can be credited with inspiring works such as But I’m a Cheerleader, Carol, The Children’s Hour, All I Wanna Do, The Miseducation of Cameron Post, very explicitly, Lost & Delirious, Loving Annabel, and Olivia, and to some extent just about every lesbian movie ever.

But its importance goes beyond its novelty and its influence. Revisiting a proudly queer movie from 1931 Germany is a reminder that our current era of queer acceptance is not the first, nor is it necessarily permanent. The existence of this film is a reminder of what was lost, not just in Germany in the 30s, but repeatedly throughout history as Christian white supremacist patriarchy attempted to erase cultures with more fluidity around sex and gender.

What I’m saying is thirsting over classic movies is an inherently political act. Remembering that queer people have always been here, and have always been hot, is a necessity if we want our present and future to be truly queer. It’s important that we continue to watch the works that are available, and continue to uncover the queer films from all around the world that are unavailable.

Know your history. Know our history. And, in the process, I hope you cum.