The True Price of Salt: On the Book that Became “Carol”

In her 1989 afterword to her seminal novel, The Price of Salt, Patricia Highsmith reflected on how difficult it was to be a lesbian in New York in the 1950s, as well as the challenges of finding a publisher for a book with two female protagonists who were romantically involved. She had just written her first novel in 1950, Strangers on a Train, a violent psychological thriller that had been marketed as a ‘novel of suspense,’ which had been sold to Alfred Hitchcock for a film adaptation, and her agent and publishers wanted her to ‘write another book of the same type.’ She was afraid of being labeled a ‘lesbian book-writer’ if she wrote a book about a lesbian relationship and thus losing the momentum she was gaining as a novelist, as it was potential mainstream suicide at the time to be an openly queer writer.

But the idea for the novel entranced her. She could not let go of it; it was that door of memory with a faint lamp-lit glow she kept coming to and peeking inside. The idea had come to her like a kind of mystical vision, which she never forgot: 1948, New York, near Christmas, at a vast department store in Manhattan, at the counter for dolls, where she had decided to work as a salesgirl because she was running out of money. The store was a chaotic labyrinth, with parents flooding its aisles in search of dolls that would travel from their shelves into boxes under Christmas trees, but one customer stood out to Highsmith. ‘One morning,’ she put it, as if beginning a great tale, ‘into this chaos of noise and commerce, there walked a blondish woman in a fur coat.’ Highsmith was enchanted: something about the woman made her stand out, and she even, Highsmith recalled, ‘seemed to give off a light,’ as though she were an atheist’s angel, for the nonbelieving Highsmith had no time for the angels of religion. The woman simply purchased a doll at her counter and had Highsmith write down her name and address on a receipt for delivery, and then she was gone. But she filled the hallways of Highsmith’s mind. She was the novel. That night, she would return to her apartment and sketch out ‘an idea, a plot, a story about the blondish and elegant woman in the fur coat.’ She wrote eight pages. ‘It flowed from my pen,’ she wrote, ‘as if from nowhere—beginning, middle, and end.’

So she decided to write the book anyway, under a pseudonym. Unsurprisingly, her publishing house, Harper & Bros., rejected it, and she had to find another publisher. But the resulting book was to become one of the most popular and revolutionary novels featuring lesbian characters in America in the last century, even as it has faded, somewhat, into obscurity. It would be about Therese Belivet, a salesgirl in a toy store, and her mundane yet extraordinary meeting with Carol, and the trans-American love story that would result from this chance meeting.

And queer readers resonated with the book. Letters from her fans — addressed to Claire Morgan, the pseudonym Highsmith had written the novel under — flooded her mailbox from week to week. ‘I remember receiving envelopes of ten and fifteen letters a couple times a week and for months on end,’ Highsmith wrote in her afterword. And even after the deluge slowed, she still received letters from both women and men right up until the time she wrote the afterword, over three decades after the book had first come out. It was a breakthrough for many of them to find a text about queer woman that had a happy ending — or, at least, the possibility of one—rather than one that ended in defeat or devastation.

Highsmith herself was aware of this, writing that ‘[t]he appeal of The Price of Salt was that it had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together. Prior to this book,’ she continued, ‘homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing—alone and miserable and shunned—into a depression equal to hell.’ Indeed, it was this ending, more than the mere fact that it contained an explicit romance on the page between two characters of the same gender, that made the book revolutionary for so many of her readers. ‘Yours is the first book like this,’ one letter read, ‘with a happy ending. We don’t all commit suicide, and lots of us are doing fine.’

Of course, not all of the letters were so filled with optimism or complacency. One of the letters, which could as well have been written in 2016 as in the early 1950s, read, ‘I am eighteen and I live in a small town. I am lonely because I can’t talk to anyone….’ In such cases, Highsmith sometimes acted as a counselor of sorts, giving such letter-writers advice. ‘Sometimes I wrote a letter,’ she said, ‘suggesting that the writer go to a larger town where there would be a chance to meet people.’ But, of course, not everyone possessed the economic ability to move. And that letter of loneliness would have meant so much more for someone whose skin was clearly not ‘passably’ white in an age where Loving v. Virginia would not even occur for over ten years, and where casual racism would almost certainly only be made worse if someone were also openly queer.

It is a testament to America’s evolution on LGBTQ rights that a letter like that, if it were written in 2016, can seem at once like the tale of someone in unfortunate circumstances and like the most mundane revelation. Many of us will recognise that loneliness, and some of us will not, having grown up in a world where we always felt more accepted for our queerness. In a way, we have come far, and we also have not come far enough. There are many American readers for whom The Price of Salt would still be a revolutionary, shocking, immoral novel, the kinds of readers who have never, to their knowledge, met a lesbian or bisexual or pansexual woman before and who imagine us all as monstrous caricatures. This is all the more so if you are trans or simply a woman of colour at all, and especially if you are someone the media still often erases, like non-binary, intersex, and asexual individuals; there are books with all such characters in them, most notably, perhaps, Keri Hulme’s novel of an asexual relationship, The Bone People, but we have far to go. I know that many readers from my own home in Dominica might well be shocked by the content in The Price of Salt, given that queerness is still deeply unusual, deeply radical, deeply subversive there, as it is in so many other parts of the world.

And Highsmith knew well how difficult it could be to be queer even in a much larger community. As she says in her afterword of the era of the novel, ‘those were the days when gay bars were a dark door somewhere in Manhattan, where people wanting to go to a certain bar got off the subway a station before or after the convenient one, lest they be suspected of being a homosexual.’

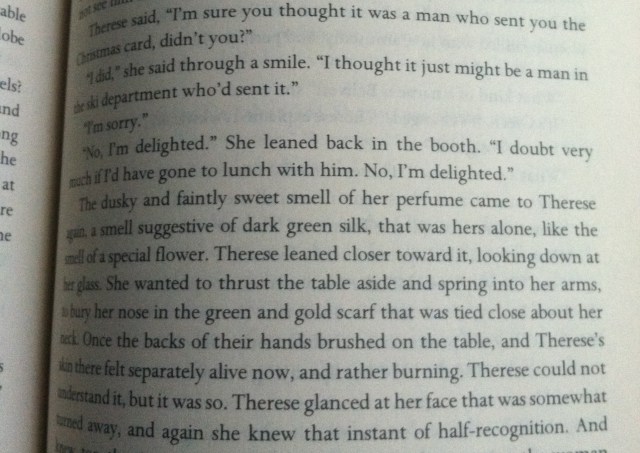

Certainly, The Price of Salt is a relatively quiet novel, tame in comparison not only to later lesbian novels like Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle but also in comparison to Highsmith’s own previous novel, Strangers on a Train. While Strangers on a Train is subversive in its casual presentation of violence and maniacal characters, starker in both than a novel like Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, The Price of Salt is much more of a slow-burning love story. Earlier lesbian novels, like Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu or The Well of Loneliness, tended to be far subtler in their descriptions of intimacy between women; Carmilla, perhaps even more important in the history of vampire literature than Dracula, is only able to depict a queer relationship by making it literally monstrous, with a homicidal romantic vampire named Carmilla attempting to bewitch and seduce a seemingly heterosexual girl named Laura before preying on her. Highsmith openly depicts lesbian lovemaking, and there is no moral imparted onto it. It is what Therese and Carol want, even as they are complex in their desires, and that is enough for the novel.

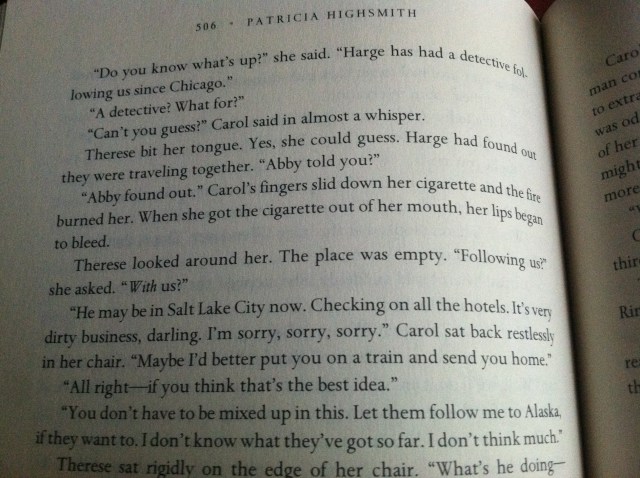

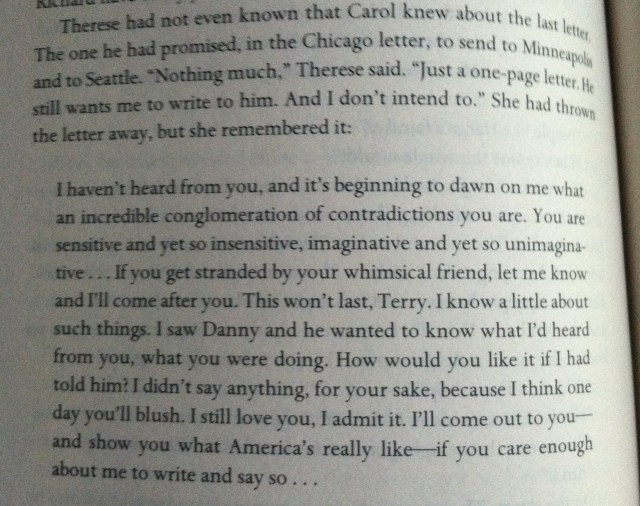

But if the novel is open about intimacy, it is also clear about the lack of a future for a lesbian couple in this time in America. Carol sums this up well when Therese asks her whether they could just run off together. It is not possible, she casually tells Therese, and Therese understands this well; it is all a pipe dream, richer and more beautiful than dream by Kubla Khan, but a dream all the same. And when Carol and Therese’s relationship becomes obvious to their former significant others, it becomes clear that the mere mention of being in a queer relationship may be enough to destroy their social standing, to rip them from their families via court cases. It is chilling that, even with our progress today, there is still that stigma attached to being queer, that sense that you cannot be a respectable parent—as Carol is told—or that you cannot really be together. Therese’s own former lover believes that lesbianism is nothing more than a ‘phase’ that can be cured by the right man, a sentiment that would be utterly unsurprising today if uttered by an evangelist. The true price of salt, of course, is still a mystery to so many.

This is a book that does something positive for queer representation by not trying too hard to do so. Writing for activism is not the same as writing for art; it’s dangerous, ironic as it may seem at first glance, to write queer characters solely or even primarily for the purpose of promoting an activist view. The danger of writing overly sympathetic queer characters is that they can so easily become solely that, characters: they become nothing more than symbols of social change, avatars of social justice, rather than what they would do best to be, which is to be like real, complex human beings on the page. The best way to help with queer activism as a writer of fiction, ironically, is by not trying too hard to be an activist, is by putting art first and activism second, if activism need be there at all. The most representative representation is the one that shows us not as a medievalesque binary of angel or demon, but rather as people who simply are whatever they are.

And perhaps that, finally, is why readers loved The Price of Salt so much, myself included. Early on, when Therese is driving with Carol to the latter’s home for the first time, she is so flushed with excitement that she suddenly wishes for them both to die, for the tunnel they are driving through to ‘cave in and kill them both,’ so ‘that their bodies might be dragged out together.’ It is at once absurd and understandable. It is possible to be so filled with something that you wish for its destruction, simply so as not to lose it. There is something so real in even the maddest moments here. And this is why I think this novel must endure: it does what the best such books do. It does not, like I saw a certain celebrated queer novel from 2015 do, attach a label to its back that says, essentially, ‘ACTIVIST BOOK HERE.’ It simply presents a narrative of people, one that may well leave salt in its readers’ eyes. And that is enough, and more than enough, sometimes.