The Journalistic Quest to Write An Accurate Story About Bisexuality

The New York Times doesn’t have a shining history when it comes to respectful and accurate reporting on bisexuality; sometimes it needs to be reminded by its readers that bisexuals exist, sometimes it writes about flawed studies that question the existence of bisexuals, or writes about “same-sex experimentation” and “lesbians until graduation” without presenting bisexuality as feasible explanation. Since the NYT as an institution has consistently presented itself as being on the fence about the existence of bisexuals, the title of their newest article on it is perhaps not surprising: “The Scientific Quest to Prove Bisexuality Exists.”

It’s a lengthy piece, and a lot of the information it presents is accurate and helpful, especially for readers without a lot of understanding about bisexuality. Respected bisexual activist, Robyn Ochs and Lisa Diamond, who has written extensively about sexual fluidity, were involved in the article, and there’s some important knowledge dropped, like the fact that bisexuals have poorer physical and mental health outcomes, and that the modern definition of bisexuality doesn’t revolve around attraction to “men and women” or binary gender. (Robyn Ochs’ definition of bisexuality is “I call myself bisexual because I acknowledge that I have in myself the potential to be attracted — romantically and/or sexually — to people of more than one sex and/or gender, not necessarily at the same time, not necessarily in the same way and not necessarily to the same degree.”) For some readers who are operating with a limited or backwards understanding of bisexuality, these things will be big news, and important to include. Much previous writing about bisexuality has focused on straight or gay researchers’ work, and it’s important that this piece speaks to actual bisexuals doing research about bisexuality.

Robyn Ochs

However, the article isn’t consistent in terms of its approach — for instance, even though Robyn Ochs’s inclusive and non-binarist definition of bisexuality is included in the text of the article, the NYT’s excerpt for their article on the NY Times Magazine homepage still reads “How a new breed of activists is using science to show — once and for all — that someone can be truly attracted to both a man and a woman.” (Emphasis added.) And while it’s great that bisexual activists and researchers like Ochs, Diamond and more are included, very little time is spent discussing their work when compared to how much space is devoted to Michael Bailey.

Bailey isn’t bisexual; in fact, much of his previous work (which was referred to in the previous NYT article “Straight, Gay or Lying? Bisexuality Revisited“) was designed from a place of personally not believing in bisexuality as a real sexual orientation, especially among men. His research revolves around measuring physical sexual arousal in response to different gendered stimuli to “prove” or “disprove” bisexuality. His work has been roundly criticized by people of a number of sexual orientations, and while the article explains how American Institute of Bisexuality has worked with him to make his studies slightly less problematic and therefore seemingly measure the “proof” of bisexuality more accurately, the fact remains that the premises of his work seem at best uninteresting and at worst offensive.

Bailey… went into an explanation of his proposed study, which I was surprised to hear wouldn’t include any actual bisexuals. Instead, he planned to test the arousal patterns of 60 gay-identified men.

“We’re interested in the role that sexual inhibition can play in people’s sexuality, in ways that might be relevant to sexual identity or capacity,” he began. “There’s evidence from prior studies that if you start with a stimulus that might turn on a gay guy — say, two guys [being sexual] — and then add a woman to the scene, some gay men are going to be inhibited by that and feel less aroused, while others won’t see their arousal decrease. A subset of bisexual-identified men might be explained by that.”

Even leaving aside the fact that he’s designing a study about bisexuality without including any bisexuals, there’s plenty to take issue with here. The clear implication is that the goal of the study is to see if at least some bisexual-identified men can be “explained away;” if a reason can be found that would account for their baffling behavior and identification — you know, any explanation at all besides their being actually bisexual. It’s also telling that, almost ten years after his famous (and flawed) study, Bailey is still obsessed with trying to measure sexual arousal to define sexual orientation. While most people can figure out why this might not be the greatest yardstick to use — not every person of every sexual orientation is going to be physically aroused by every person of the gender(s) they’re attracted to! Some lesbians are more into Shane, some more into Carmen! — it’s particularly frustrating when used to talk about bisexuality.

Bisexuals have historically been imagined as sexually predatory, “greedy,” “slutty,” or as necessarily requiring simultaneous sexual activity with people of different genders — essentially, bisexuality has been defined by mainstream culture as an inherently sexual and sexualized category, sometimes little more than a genre of porn. In contrast, with identities like “straight” or “gay” we’re much more willing to recognize that there’s more to how someone lives their life than their sexual desires; we understand that being gay, for instance, also has cultural connotations, a history, social rites of passage, and emotional and psychological contours. For this reason, when sexual behavior or arousal are the only factors considered important in studying bisexuality, it comes across as worse than just a less than effective research method; it reads as though the researcher is buying into the assumption that sexual behavior is the defining inherent characteristic of a bisexual person.

We also allow people to identify as straight or gay outside of sexual experience; straight people are assumed to be straight even before they’ve become sexually active, and gay people are usually (although not always) believed by others when they come out as gay even without same-sex sexual experience. Why, then, do researchers remain skeptical of someone’s bisexuality — when that person identifies as bisexual, has dated multiple genders, has maybe faced stigma from both the straight and gay communities but continues to identify as bisexual — unless they can measure a large enough pupil dilation at the sight of a particular set of genitalia? Many of the people quoted in this piece seem willing to take straight and gay people at their word, but when it comes to bisexuals, are fixated on what they call the “the tricky matter of identity versus behavior.”

To be fair, the article’s premise is defined as exploring the “scientific quest to prove bisexuality,” and so in that light all the time that’s spent on talking about Bailey might be kind of defensible — after all, he’s one of the only researchers still working on that problem, since others have long since accepted that bisexuality exists and have moved on to other questions, like “Why are bisexuals more likely to live in poverty and be food insecure?” or “Why do bisexual women report higher rates of intimate partner violence?” But unfortunately, aside from reporting on flawed research, the article itself also seems to come in with some flawed assumptions, or at least assumptions based in a certain level of male privilege.

Benoit Denizet-Lewis, the author of the NYT piece, identifies as a gay man. (Although he’s briefly shaken in this identity when a researcher tells him that his pupil dilation is similar to that of a straight man, he ultimately decides that “no matter what my pupils suggest… It doesn’t feel true as a sexual orientation, nor does it feel right as my identity.” It’s unclear why the writer doesn’t choose to apply these same insights to others in the story.) The two people he talks to most in constructing this story are John Sylla and his partner Mike Szymanski, who are the president of the American Institute of Bisexuality and co-author of The Bisexual’s Guide to the Universe respectively. Input from bisexual women was minimal; although Diamond and Ochs are quoted, it’s in small soundbites, with little if any analysis. As a result, a familiar problem of LGBT media coverage develops: male bisexuals and their experiences are the most heavily drawn from, which gives a skewed impression that a) the problems of male bisexuals are the most pressing, and b) that the problems of male bisexuals are the problems of all bisexuals. Just like gay men and lesbians face different challenges and oppression — lesbians aren’t usually thought of as accessories for straight women who love shopping, and gay men aren’t usually quizzed about how they have penetrative sex by strangers — bisexuals of different genders face very different problems.

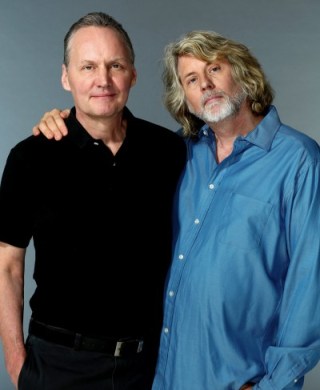

John Sylla and Mike Szymanski, via GLAAD

If Denizet-Lewis’s article was the only text about bisexuals a reader was ever exposed to, they would likely conclude that the biggest issue facing bisexuals was the collective refusal to believe that bisexual men really exist, and problems with successfully dating people of the same gender as them — because these are the issues that the bisexual men who are the focus of this article experience in their own lives. The only paragraph devoted to the issues specific to bisexual women suggests that their biggest challenge is dating lesbians — basically, the same problem the bisexual men Denizet-Lewis talks to report with gay men.

Bisexual women also struggle to find lesbians willing to date them — or even to take them seriously. The bisexual activist and speaker Robyn Ochs told me that when she realized in college that she was bisexual, she hoped to be honest about that with the lesbians on her campus. “But it didn’t feel safe for me to do that,” she said. “They said that bisexuals couldn’t be trusted, that they would inevitably leave you for a man. Had I come out as lesbian, I could have been welcomed with open arms, taken to parties, invited to join the softball team. The lesbian red carpet, if you will. But for me to say I was a lesbian would have required that I dismiss all of my previous attractions to men as some sort of false consciousness. So I didn’t come out.”

The focus on this issue has the effect of pitting two groups of women against each other and of positioning individual lesbians as the cause of bisexual women’s struggles rather than systemic oppressors like heterosexism or monosexism. While some individual bisexual women may feel that way, plenty of solid research indicates that as a group, bisexual women have much larger and more complicated problems. Denizet-Lewis doesn’t seem to have set out to write an opus about the current challenges facing bisexual groups, which is fine, but the fact that there have been so many recent and hard-to-miss stories bringing to light oppressions unique to bisexual women — like the recent headline that almost half of bisexual women have been raped, a percentage much higher than either straight women or lesbians — makes the highlighting of dating woes as a supposed major problem seem even more egregious. The fact that the majority of the experiences focused on were those of men sets the article up for this kind of misunderstanding, and that’s even before looking at the fact that the vast majority of the people spoken to for this article appear to be white and cisgender, when many bisexuals are transgender and/or of color. Given the ways in which cultural assumptions about bisexuals — that they’re hypersexual, duplicitous, and not to be taken seriously — overlap in meaningful ways with cultural assumptions about trans people, people of color, and trans people of color, it seems especially unhelpful to focus on the experiences of cis white bisexual men.

It especially seems like a misstep to avoid looking at the growing list of ways in which bisexuals experience oppression because if the question is really one of “proof” that bisexuals exist, isn’t the already-published research about the ways in which bisexuals experience unique marginalization already pretty compelling in that regard? More than the degree to which one’s pupils widen when being shown footage of a threesome, it seems like given the fact that people who identify as bisexual all experience similarly poor levels of health, sexual assault and violence, mental illness, alcohol abuse that are more extreme than and distinct from those of other sexual orientations, there’s something pretty real going on there.

Hopefully this conversation, inaccuracies and all, can be the final word in the discussion of whether bisexuals can be proven to exist: they do. Maybe if everyone can agree about that, we can move on to the next step: letting actual bisexuals speak about their experiences and their community, and taking them seriously when they do.

In order to make sure that the comments section on this article is a healthy and welcoming place for our bisexual readers, please note that any comments that question the validity of bisexuality or sexual fluidity as a sexual orientation, question Autostraddle’s decision to publish pieces discussing bisexuality, or make essentialist claims about bisexual people (ex. bisexuals are cheaters, bisexuals turn out to be gay) will be swiftly deleted.