The Curious Case of Alex Parks, the Celesbian Who Briefly Was

She was 19, and she wore battered Etnies skateboard shoes, torn jeans, and looked like Shane McCutcheon before Shane McCutcheon existed, or the lovechild of Fairuza Balk and Andrea Gibson. She was really into Ani DiFranco. She was heartbroken, jilted, and talked about it feverishly… yet none of this mattered as much as her ability to carry a tune like Gary Jules’ younger sister.

In the summer of 2003, her psychotherapist father signed her up for the second season of the lackluster rival of Simon Cowell’s wildly successful Pop Idol, BBC’s Fame Academy. Having long considered a career as a professional singer a pipe dream, she was more interested in studying clowning and acrobatics and The Hub Theater School, traveling to Spain and Amsterdam to work as a mime, and getting out of Cornwall, for good. By that October, however, her voice and name — Alex Parks — quickly became known and acclaimed throughout the UK.

After Parks won Fame Academy in 2003 (a show that’s name implied its contestants were being strategically groomed for more than the Warholian fifteen minutes), she would go on to release a 2x Platinum album, all while voicing concerns to The Telegraph that she was being portrayed as a “spikey-haired Cornish lesbian” or was doomed to a life in the “cheesy pop world.” In addition to a record deal, the BBC offered Parks a BMW sportscar, an apartment in Notting Hill, and what seemed like a lifetime supply of champagne. When the network asked Parks — who grew up in a 300-year-old cottage in a working class neighborhood — if they could record her around her new digs for a documentary about her, she refused. “They want to film me in the flat and driving the car, with me saying: ‘Oh, I am so thankful for everything you have given me, where you have put me, ra ra ra,'” she told The Telegraph.

Shortly after her moderately successful sophomore album’s release in 2005, Alex Parks amicably cut ties with her record label and vanished — but not in the way pop culture celebrities typically do. The Meme Star of Questionable Talent (William Hung, Chris Crocker) and The One-Hit Wonder (Lumidee, Daniel Powter) archetypes that have increased in ubiquity in tandem with reality television usually fade away. Parks’ talent was not questionable but undeniable, and she did the opposite of passively falling into obscurity: she deliberately turned invisible.

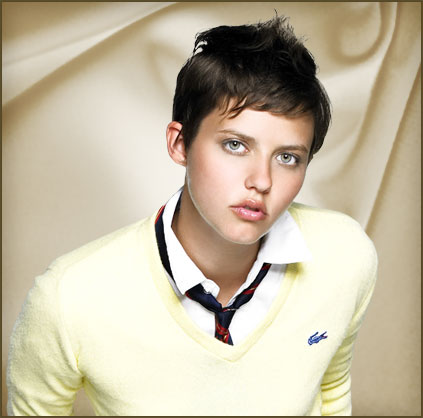

Parks Performing at Clotheshow Live in 2003

Earlier this month, days after the 11th anniversary of Parks’ Fame Academy win, Daily Star’s Mike Ward revived the case of her disappearance:

I realise I could ask the same about a million and one talent show competitors in the years since, people we’ve briefly become super-excited about and then quickly forgotten, fickle buggers that we are. But most of them you can Google in a matter of seconds to get at least a rough indication of what they’re up to these days, before going: “Oh, righty-ho.…” and getting on with your day. Alex, on the other hand seems to have disappeared off the face of the earth – and, more to the point, seems to have done this intentionally. Which not only seems a shame (I really liked her: great voice, real charisma, I actually bought both her albums), but also makes her story oddly fascinating. Alex’s Wikipedia entry hasn’t been updated in years. Her website has been frozen in time since 2005. Twitter delivers nothing relevant, as far as I can see. Only Facebook seems to offer a vague clue: an Alex fan site with a more recent entry, hinting at a comeback whose promised date has come and gone.

Along with her eclectic professional interests (Parks continued to mention her desire to become a mime in interviews) and open resistance to the BBC’s attempts at exploitation, there were other signs that Parks would not be a good fit for fame. When asked in November 2003 if she felt like a career in music was sustainable given David Sneddon’s retirement less than a year after winning the first season of Fame Academy, she responded tentatively:

It does scare me, yeah. I’m going to do everything that I can to not let that happen. I’d be very gutted if I stopped loving it as much as I am now, in a year. I want it to go on for years and years.

She also admitted to finding celebrity culture alien. “People recognizing you, people wanting things of you, like just a small signature. I find that quite mad, that people just want you to write on something or want something of yours. It’s a compliment, but it’s quite hard to understand.”

I’m not interested in Parks because I am interested in smoking a one-time celesbian out of her hard-earned hiding spot. I’m interested in Parks because she pulled a hell of a virtual vanishing act. Disappearing from the limelight and disappearing from the internet are two different things. As Ward mentions, even when a reality celebrity fades into obscurity, he or she still remains fodder for a late-night “whatever happened to…” search engine binges, and a Twitter handle or Facebook fan page is bound to be rendered within the results; the most seemingly has-been stars of reality programming can be found online. Even though he announced his retirement years ago, Fame Academy winner David Sneddon’s Twitter and Facebook fan page are mere clicks away. I sent tweets to a handful of Fame Academy‘s former hosts and “students” asking about Parks’ whereabouts and well-being without any certain response.

Despite our favorite reality television personalities no longer receiving screentime, the internet enables us to speak about them in the present-tense. Without the consistent play-by-play offered by Instagram or ill-advised real-world stalking, it would be tricky to verify Whitney Mixter’s ongoing existence. The “digital deletion-as-death” metaphor is an obvious one, so much that a program to assist users in removing their social media profiles is named Web 2.0 Suicide Machine and there is a LifeHacker article shamelessly titled, “How to commit Internet suicide and disappear from the web forever.” No one knows who Alex Parks is because she doesn’t exist at the click of a mouse — we only know what she was as indicated by old interviews and fan-uploaded YouTube clips of her Fame Academy performances.

What Parks did was not only mysterious; it was also enviable, even romantic. The goal is to have a control over web presence, for it to be a tool. But when other people are heavily involved in that interaction, control is not always guaranteed. I remain as guilty as the next person of dreaming of a day that’ll never come: the one when I delete Facebook. As Emma Healy writes at The Hairpin:

Appeals to disconnect and unplug will always find an audience no matter how slapdash or rote they might be. It is frightening to think that you might be a willing partner in the steady proliferation of your own sadness just because you’re checking Facebook all the time. It’s unsettling to remember that corporations can permanently alter the definitions of words like “friend” and “favorite” in the blink of an eye, or to consider that the concept of “connection” is just as mutable. It is scary to be told that the world is changing for the worse and that you’re a part of it. It is scary to look inside yourself and find that maybe you agree. Reading essays that tell me to get off social media is a way to confront my own insecurities, to question my own motivations for staying.

The same goes for case studies of people — people like Alex Parks — who’ve actually done it.

It was easier for Parks to vanish in 2006 than it would be today. The internet was less of a requisite beast, and her digital following was directly in contact with her music, never her. Parks, whose success largely predated the concept of Vining, Tindering, or posting one’s dinner to Facebook, escaped without a single ghost — which is more than many can say, even the dead (see: queer ex-Johnson & Johnson heiress Casey Johnson‘s final social media footprints). To “pull an Alex Parks” in 2014, one would have to somehow reach Bieber levels of success without leaving so much as a blog post behind.

Across the pond in the United States in 2005, another queer girl with pre-Shane McCutcheon sensibilities was also riding the reality television fame wave. 21 year-old Kim Stolz landed a spot in the top four during the fifth season of America’s Next Top Model.

Kim Stolz

But despite being another token gay girl in a sea of limelight ambition in the mid-aughts, Stolz didn’t vanish. Instead, she reincarnated herself again and again, all while maintaining a Twitter following of 12,500. Earlier this year, the model-turned-veejay-turned reputable lesbian bar owner-turned banker eventually turned author and published Unfriending My Ex: And Other Things I’ll Never Do, a collection of essays about her experiences at the apex of reality television glory and social media. “As for the MTV and Top Model fans who contact me through Facebook,” she writes in a tone that parallels the one Parks used when speaking about autograph requests, “I was constantly amazed by the illusion (or delusion) of connectedness that these (almost) strangers felt toward me. They believed that the mere acceptance of a friend request was the first step in our budding friendship — and I suppose that is exactly what I encouraged when I accepted them.”

Parks is now 30, yet the webmasters of her Facebook page and fansite cling to hope of a resurrection of messianic proportions. Just as much as the internet has lost track of Parks, it has retained her, perhaps in the most flattering light possible: her talent is all over, yet she is nowhere to be seen. Hopefully her current life mirrors this. Perhaps Parks finally made it to Amsterdam and is hiding in plain view, with a full face of mime makeup.