Solve Crossword Puzzles, Fund Abortions Across the Country

If you’ve been solving along with the Autostraddle mini and midi crossword puzzles over the last six months, you may have become familiar with the experience of seeing yourself and the things you care about represented in a puzzle. We (Rachel Fabi and Brooke Husic) are two of the crossword constructors for Autostraddle, and we have made it our mission to create puzzles that reflect queer joy and highlight some of the things we care about, and that we believe the solvers on Autostraddle also care about. To that end, we thought you might also be interested to know about a different passion project we’ve been working on for the past two years: a crossword puzzle fundraiser called These Puzzles Fund Abortion.

As anti-abortion laws spread around the country, we, along with our friend Claire, found ourselves grasping for a way to help people in need of abortion care. We brought together some of the best crossword constructors out there to create a pack of puzzles all themed around reproductive justice in order to raise money for abortion funds as part of an annual fundraiser hosted by the National Network of Abortion Funds (NNAF).

In exchange for donations that support five abortion funds around the country (the Baltimore Abortion Fund, Chicago Abortion Fund, Indigenous Women Rising, Tampa Bay Abortion Fund, and Wild West Access Fund of Nevada), you can receive a pack of 16 crossword puzzles that are all around the same level of difficulty as the A+ midi puzzles, or a New York Times Tuesday. Every dollar we raise goes straight to the funds we’re supporting, who in turn help people afford abortions, including support for their travel. We poured our hearts into this project, and we hope Autostraddle crossword lovers will join us in supporting abortion access through puzzles.

You can donate to receive the puzzles through our Fund-a-Thon page until May 31, 2023, after which the puzzles will be available through the These Puzzles Fund Abortion website. We are also selling TPFA merch through Bonfire until May 24.

Here’s a puzzle from the pack that you can solve today!

How Polyamory Pushed Me to Prioritize My Pelvic Health

I got my first yeast infection at 30. It was diagnosed during a pelvic exam with my primary care physician in December 2020, a month after my divorce was finalized. It was an especially painful exam because of the infection, and I wept for a long time when I got home. My ex and I were packing up to move to different states, but they took the time to talk me through some of my more complicated feelings: Namely, that I felt ashamed for “not taking care of myself” and thus getting an infection.

At the time, I felt ashamed about anything pertaining to my pelvic health. My first relationship had been an abusive nightmare in which my weight had been a point of contention — because if I were “less fat, then we could have better sex” — and that had a lasting impact on me. Then the partner I eventually married said I was hypersexual and would often ask me if I had showered recently when they could smell odor from my vagina — even if we were kissing or if they were touching me in a way that turned me on. I didn’t trust my libido or my body for a decade.

In July 2022, seven months into being one-third of a closed polycule, I was diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis and a severe UTI. This time I didn’t feel ashamed — I felt surprised. My symptoms were so sudden and so severe that I was forced to crawl out of the bathroom because the pain made me so weak. Both of my partners went with me to the emergency room, and we all thought this would be a one-time occurrence.

It wasn’t. That month alone, we went to the ER four or five times, and then I was admitted for a ten-day hospital stay. One doctor’s comment that I was “a bag of mysteries” became something of a motto each time I met a new provider. That was just the beginning. Fortunately, communicating openly and often about sex and pelvic health with my partners has helped me advocate for my needs, and now I’m finally on a path towards healing.

Deciding to explore polyamory for the first time at the start of 2022 was incredibly scary. In past relationships, polyamory had only ever been presented to me as a punishment or an ultimatum. Choosing to try it for myself felt empowering, but it also felt like skydiving with no parachute. I feared losing one or both of my partners, worried that I wouldn’t be able to handle my own feelings of jealousy, stressed about getting it wrong at every turn.

Sometimes I do get it wrong. All of us do. But by developing a strong base of communication and intentionally talking through issues as they arise instead of letting them fester, all three of us have been able to not only show up for ourselves, but also show up for each other. We set boundaries with each other and call each other in if those boundaries are violated. Our apologies include four parts: asking for consent, apologizing, naming what we’re apologizing for, and creating a plan for growth and improvement. We check in each day, often multiple times a day, to ask how we’re doing with our mental, emotional, and physical health; what tasks we need help accomplishing; and how we can support each other. We prioritize safety over productivity, and we strive to take each other at our word.

These practices translate directly to how we communicate about sex and intimacy. As a fat, chronically ill, increasingly disabled survivor whose sex drive created problems in my marriage, I’ve struggled to state what I want from my partners. I’ve feared that I want too much, too often, that seeking pleasure makes me selfish, and that asking to be touched in certain ways is too demanding. I’ve also worried that not wanting to have sex when my partners do will make them not want to sleep with me ever again. I’ve feared that saying “no” will birth bigger problems for us. In the last year, I’ve learned that none of these things are true and that being honest about what intimacy looks like for me at any given moment is the healthiest thing I can do.

By beginning to heal my relationship with intimacy, I’ve also begun to heal my relationship with my body. This has been especially integral due to how my body is changing. When I first started dating one of my partners, I began experiencing a new type of chronic pain that required me to walk with a cane. Suddenly, I had gone from having an invisible illness to being visibly disabled, which was difficult to process. I felt betrayed by my body and fearful of the future, especially as the pain got worse.

I’m a fat liberationist and genuinely love my fat body, and being with two other fat people has further radicalized me. But having sex as a chronically ill and disabled person is new to me. It requires me to be completely in my body during sex — something I avoided in past relationships to escape potential shame, pain, and discomfort. Now, for the first time, I have partners who encourage me to explore toys, tools, and positions that are as accessible as they are pleasurable. One of my partners also experiences chronic pain, and all three of us believe sex should be as shame-free and pleasurable as possible for everyone, however they choose to participate. For me, the way I participate in sex fluctuates constantly — especially because sex of any kind can be wildly painful.

Since my hospital stay last summer, I’ve exhausted the available urological tests and still struggle with persistent, resistant UTIs. I’ve been diagnosed with PCOS and may also have endometriosis. In December, I had a dilation and curettage procedure to determine whether my rapidly-thickening endometrial lining was cancerous. Thankfully, it wasn’t.

After a lifetime of being disregarded by doctors because I’m fat, I was accustomed to never getting answers — now, thanks to the communication skills I’ve practiced in my polycule, I refuse to be ignored. Instead of simply living with inconsistent and debilitating periods, chronic pain, and bizarre bladder symptoms because I’m afraid to acknowledge that something might be wrong, I’m advocating for myself. I ask my doctors to follow their hunches, encourage them to examine my symptoms from new angles, and ask scary questions. I demand to have tests and procedures done for peace of mind, even if they won’t reveal any new information. I state my boundaries upon meeting each and every doctor. If my boundaries as a patient are violated, I state that in the moment and then pursue new care paths with other providers. My ability to do this is a direct result of the communication and trust I’ve built with my partners in talking about sex, intimacy, illness, and pain. It also helps that I always have one, if not both, of them with me — and whenever I falter, I can silently communicate with them to step in and help me advocate for my needs.

The first time I considered asking for a hysterectomy was right before I got married. When I brought it up with my doctor, he told me it was an invasive procedure that required more thought than he believed I’d given it. Now, six years later, an OBGYN will be removing my uterus because I believe it’s the best thing for me, and she believes the procedure will grant me some of the freedom and relief I’m desperately seeking. Thanks to my self-advocacy and a bit of luck, I finally found a doctor who listens to and respects my needs in this arena and doesn’t pin my illnesses on my weight.

Were it not for my partners and our commitment to talking through everything, all the time, especially when we’re struggling, I think I’d still be suffering. Although I never could have predicted it, learning how to practice healthy polyamory has taught me how to advocate for my health needs without even a modicum of shame.

My Hysterectomy and Early Menopause Reshaped My Sexuality — So My Queerness Found New Spaces to Inhabit

There is a distinct smell to the place; handsome and even topiary, as if cultivated specifically for watering holes on the brink of implosion via neglect. The smell only congregates in relatively ancient places and spaces; to grok when you smell it, you must have a sort of affinity for old things. To me, the stench of mousy, mossy mold is intimately — and infinitely — charming. The smell has always smelled like freedom to me, because it is so undeniably impenitent.

It is karaoke night at Sullivan’s, a bar that used to be “dangerous.” It was better then, obviously. Now it is fraternal; the original, delightful decay and decadence of age and realness are now covered — or rather, smothered — by AXE body spray. The space — once smelly and old — repurposed into a shrine for khakis and boat shoes.

The renovations do not stop the woman I’m dating from grabbing the mic and mashing up Carly Rae Jepsen and Trent Reznor.

Head like a hole.

Call me maybe?

I fall in love with her immediately.

Back at my apartment, we watch lesbian porn and fuck each other into the morning.

But an additional ribbon of time unfurrows from our embraces, and I suddenly find that my body is buckled over in the kind of agony that seems to swing the self into the sweet hereafter, ever so slightly. My only comparison is giving birth; I see my child in my mind’s eye and wonder if I am actually going to die in this timeline, leaving her motherless.

I am conscious enough to know that something profound has happened but not conscious enough to imagine egress from it.

As it turns out, an exploding ovary is about as painful as giving birth, at least in my experience. This bodily oxidation is often punctuated by other culprits, as it was in my case. That is, a disease of the uterus, a disease that is often allowed to fester inside the bodies of those of us deemed incapable of narrative, those of us deemed “dramatic.”

I undergo an emergency hysterectomy because the endometriosis inside of me has matured and grown its own blood vessels. It hugs my uterus to other organs and reaches its damn-near-conscious tentacles into the hollows of my anus. Before going under for surgery, I remember all of the times, all of the years, I’d complained about pain, never to be believed.

And so here we are.

Stage Four Endometriosis.

I didn’t even know the disease had progressive stages.

Before I blackout entirely, I think, All I want in this wretched world is a fucking cheeseburger.

Had I died in surgery, this would have been my last thought in this plane of existence, and somehow, I believe this speaks volumes about who I am, fundamentally, as a human.

A year after my full hysterectomy — and subsequent menopause at the age of 32 — I am desperately waiting to hear from friends at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas. A white man — as is often the case — has just won the record for deadliest mass shooting in the history of the United States, an appealing title, it would seem, for those in society given the most and yet somehow, producing the least.

My now ex-girlfriend spots me in distress outside of a local coffee shop. Reflecting her perennial generosity of spirit, she offers me comfort and then says, delicately, that she’s leaving town with her new girlfriend. Not only is she leaving town, she’s relocating to San Francisco, a city I will forever associate with making gay porn and creating queer communities with other sex workers.

The inertia of the moment feels like time travel. Hadn’t we just been in one another’s beds? She was my last lover, after all, and now she’s with someone new?

I espy my body as if from the outside and realize that it is almost 100 pounds heavier than when she and I were last entangled. Multiple timelines of violence and growth, expansion and extinction collapse in on each other and I have the distinct feeling that I’ve been left with nothing.

Empty. Dark. Cavernous. Large.

Good luck, is all I can muster. And I walk away.

I used to get turned on in libraries, before my hysterectomy.

Not because I had a specific lover in mind, necessarily, but because all of the wisdom therein appeared, to me, to be accrued in one singularity, a black hole of infinite potential.

It didn’t matter much the library; I got lovers’ butterflies inside new ones with Aerogel insulation and wildly colored acrylic railings just as I did in old ones with rolling oak ladders and neo-Greco atriums soaring over marble floors.

My lust-filled obsessions were indicative of my fetish for knowledge and, of course, my affinity for old things.

I was aroused by thoughts of growing; little did I know that once I reached my true size, I’d stop feeling aroused all together.

My birthday is in five months. I will be 39.

I used to keep a detailed, numerical record of my lovers because I took pride in amassing many. In my late twenties, I stopped the habit, after tallying more than one hundred.

And yet, in the spaces between my last girlfriend and my 39th birthday, I can count the number of lovers I’ve had on one hand. There is phenomenological immensity to this fact, and mostly because the quantitative change to my sluttiness has happened so swiftly. Indeed, I now identify as asexual.

Even if you count the men I fuck for money, my laundry list of lovers is still modest enough to appeal humble to the most priggish Puritan.

So here I am.

Single. Round. And pushing middle-age.

But I am also, now, preternaturally unapologetic and percussively boisterous. Where once I found solace in the sleepy mornings of post-coital vulnerability and sexually charged reciprocities, I am now content to spend my moments of existence companionless. Antithetical, perhaps, to the popular contention that having more sex will fix the plague of loneliness, my asexual queerness feels larger — unadulterated from social expectation and divorced from whoever may be in my bed at any particular moment. In this way, my queerness fills up the spaces I thought were reserved for other things: friendships, teaching, mothering, just to name a few.

That is to say, my dynamics with others are necessarily intimate, now, but not sexual. My queerness is too wild to be categorized. It has neither “management procedures,” as Foucault critiqued in his Repressive Hypothesis, nor is it situated within the “nature of public potential.”

Where once my sexuality flourished in the spaces of the unknown, it is now content to be still.

My structure of self, now a handsome and topiary smell to the empty, dark, cavernous, and large spaces of narrative, seems to be expanding into the vastness of space and time. I am alone. But I am large enough to let in the prism of light, reflecting back all the colors of the rainbow.

As a Nonbinary Abortion Activist, Planning a Pregnancy Is Complicated — And Hopeful

The day I get my IUD removed in the summer of 2022, my doctor asks me if I’m excited to have another baby.

I’ve just gotten off a consulting call with a new client, a reproductive health organization offering abortion services. A week prior, I helped crowdfund $5,000 for abortion funds, helped another organization write gender-inclusive language practices for their communications team, and sent a baby shower present to a friend expecting her second baby.

“Well,” I say. “It’s complicated.”

My compromise was to hire a doula who advertised as gender-, size-, and health-inclusive. She was the only person on my care team who took care to clarify my pronouns, to ask how I felt about gendered terms for my body and my parenting journey, to ask about my relationship and my identity and my values. During my 38-hour labor, she was the person who asked me if I consented to interventions, if I wanted to pause and take time to think, if I was ready to continue.

Months after I gave birth, after an unplanned C-section and a postpartum depression diagnosis and a relapse of PTSD, I wondered how that experience might have been different if I’d felt like I could be open about who I am. If there hadn’t been a part of me that was distracted by keeping the glass door on that closet, would I have been able to take more time? To ask for more space? To be less afraid to push back?

Even in the best of moments, pregnancy is an exercise in the unknown.

What if?

He moves for the first time when I’m in the middle of talking to a caller about her abortion experience two years prior. She and I are the same number of weeks pregnant. Her voice is uncertain, caught between anxiety and hope. She wants this time to be different.

When I tell a friend about it later, she asks me how it felt.

“Tender,” I say. “Honored. It takes a lot to trust someone with that kind of vulnerability.”

“No,” she says. “I meant about the baby.”

Is it unethical to have a baby when the world is literally on fire?

Will the people I organize with think less of me for having a baby right now?

How much of wanting another baby is about wanting to heal the trauma from my first pregnancy? If the answer is “any,” is that too selfish?

I read even more femme now than I did with my last pregnancy — is it even worth it to try to be out to doctors?

Is trying to get pregnant right now hopeful or insane?

Her answer:

“Does it matter?”

During my pregnancy, I start and stop half a dozen books, unable to get through the gender essentialism. Your body was made for this, mama. Women have been doing this for generations. This is the core of divine femininity.

In The Natural Mother of the Child: A Memoir of Nonbinary Parenthood, Krys Malcolm Belc Writes, “Nothing about being pregnant made me feel feminine. This body is what it is: not quite man, not quite woman, but with the parts to create and shape life.”

Yes.

I take notes on direct action and legislative advocacy and clinic support in a FUCK ABORTION BANS T-shirt with a bottle of prenatal vitamins sitting on the corner of my desk. On the other side of my office door, I can hear my toddler sprinting through the house, followed by two attentive dogs and one attentive parent.

It is the calmest I’ve felt in weeks.

“Well,” I say. “It’s kind of a weird time to have a baby.”

“Oh, honey,” she says, picking up her forceps to remove my IUD. “Isn’t it always?”

I’m Sick of White Women Centering Themselves in the Struggle For Reproductive Justice

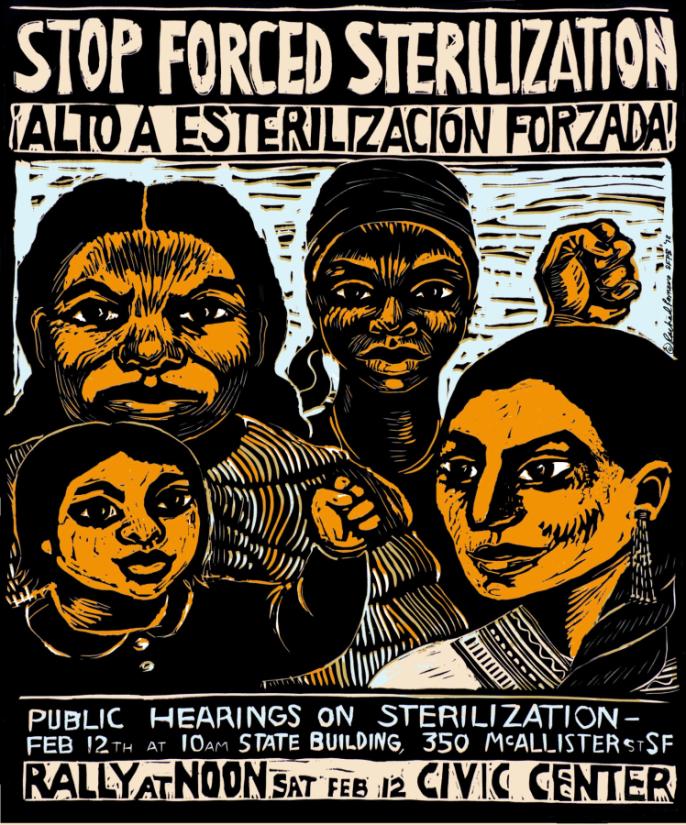

Feature image via Georgia State University Library Exhibits.

This piece has been a long time coming. On June 24th, 2022, I sat next to my mother on the couch in our family home. Some trashy reality television was probably playing in the background. I checked my phone and I see the notification from CNN on my phone.

Like so many people, the devastation I feel about the Supreme Court’s federal ban on abortions is to a point where words don’t feel adequate. We all have the right to feel our pain and express our pain. No one should dismiss or invalidate anyone’s hurt. Sharing my pain about the ruling with others – talking freely and crying out frustrations with loved ones in safe spaces – is one of the most effective ways of coping for me, personally. Community is healing.

While trying to process everything, I noticed a certain pattern of comments from tapping through Instagram stories and popular Tik Tok videos on my FYP:

“I can’t believe women no longer have reproductive justice.”

“The position of women in society is going backward.”

“Women’s rights were taken away.”

All of these comments carry truth, and I’m not trying to completely negate them. The overturning of Roe v. Wade is a major step back. But, these comments are over-generalizations. We need to be intersectional and reframe our conversations surrounding reproductive justice. Womanhood isn’t an isolated identity and it isn’t a monolithic group. What white cis women today are experiencing is what women of color have experienced for decades, for centuries. Black women are routinely denied or mistreated in reproductive healthcare to the point where the lives of Black women are at risk. Modern gynecology exists because of cruel experiments that were forced upon enslaved women in America. There is a long and extensive history of the bodies of women of color being exploited in “the name of medical progress,” misunderstood, and not receiving necessary care.

Also, these comments erase trans, gender nonconforming, and nonbinary (TGNC) folks from the fight for reproductive justice. According to the Positive Women’s Network’s page on trans-centered reproductive justice, “One in three TGNC people delayed or avoided preventive health care, like a pelvic exam of STI screening, out of fear of discrimination or disrespect. This number is even higher – almost one in two — for transgender men.” Many trans people buy hormones outside of the health care system because they do not have adequate resources to safely obtain them.

There are even worse comments like:

“You messed with the wrong generation.”

“This time, we’re serious.”

These so-called “witty” social media captions are ignorant and disrespectful to history and activists who put immense physical and emotional labor toward freedom and liberation. Also, what does “we’re” mean exactly? Who’s “we”? It seems like the people behind these comments are trying to speak for everyone and putting themselves at the center.

Time and time again, many white women only stand up when it directly affects them. As a cis Latina, I know I can’t speak for every group. I will say that I’m tired. I’m tired of the white women that come to protests in Handmaid’s Tale costumes and hold up signs that say “we are the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn.” I’m tired of performative activism on social media. I’m tired of the conversations that exclude the distinct issues of women of color and TGNC people in reproductive justice.

Why has this piece been a long time coming? One reason I struggled to accept is that I was afraid of upsetting people. I was afraid of comments that went along the lines of “not everything has to be about race” (everything is about race) or “you’re blowing it out of proportion”. But, I’m not responsible for white fragility, nor should I coddle it. I don’t want my silence to contribute to the erasure of TGNC people.

Whiteness needs to be decentered from the fight for reproductive justice. I’ve always said that history is a powerful tool for transformation and rethinking – I want to share a piece of history that does just that, the history of mass sterilization and reproductive genocide of Puerto Rican women between the 1930s to 1970s.

HHR, ““Stop Forced Sterilization,” c. Rachael Romero, San Francisco Poster Brigade, 1977,” Georgia State University Library Exhibits, accessed August 26, 2022.

I learned the history of reproductive genocide in Puerto Rico during my last year of high school. I was never taught it in a class – I searched for the information on my own from a yearning to learn more about who I was and my history. During my time in a former organization on my college campus called Planned Parenthood Generation, I worked with another member of the group (and the only other woman of color in it) to organize a panel that addressed the history of the struggle for reproductive justice for women of color. I made it my mission to bring up the sterilizations and cruel experiments performed on Puerto Rican women because silence is erasure. It is my mission now to use this history to expand dominant conversations on reproductive justice.

Freedom of any kind looks different for everybody, but my favorite definition of reproductive justice is from SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, which states that Reproductive Justice is the:

“human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”

The only thing I’d add to that definition is that reproductive issue is a human right regardless of race, gender, class, and ability. Reproductive justice is not just a woman’s issue. It is an issue of white supremacy, colonialism, capitalism, homophobia, ableism, and transphobia. It should always be at the forefront of human rights movements regardless of whether white cis women are directly affected or not.

A quick history lesson to understand the main history lesson. Puerto Rico was originally called Borikén and was inhabited largely by Tainos. In 1493, the Spanish invaded, colonized, and renamed the island. In 1917, The United States claimed colonizer status of Puerto Rico from the Spanish-American War. Puerto Rico’s been a colony ever since, and while it’s technically labeled as a “commonwealth” or “U.S. territory”, I don’t want to use any bullshit sugarcoating or euphemisms to hide the inherent violence of colonialism. This context is critical to understand because the U.S.’s reproductive control over Puerto Rican women’s bodies was a demonstration of colonial power.

The acquisition of Puerto Rico was a part of this fantasy U.S. rulers had of Manifest Destiny. American expansion was encouraged in the name of “civilizing” nonwhite individuals in different lands. So it was basically having a white savior and god complex. There was also an enthrallment with “neo-Malthusian theory,” a belief that “population control” was essential to human survival and connected economic status with genetics. The underlying logic behind it was that the rich were rich because of “good genes” and the poor were poor because of “bad genes.” Do y’all see this pattern of coded language? Anyway, the theory also dictated that it was the responsibility of the rich to dispose of the poor or else they’d be a detriment to society and cause overpopulation. These ideas fueled the rise of eugenics, which was at the root of the mass sterilization of Puerto Rican women.

Charles Herbert Allen, a U.S.-born politician, became the first governor of Puerto Rico after the U.S. seized the island. In his view, the island was “underdeveloped” because of overpopulation and the “excess” of people needed to be “taken care of.” Fuck centuries of colonialism and the denial of sovereignty as the roots of problems within Puerto Rico, I guess.

Puerto Rico, 1960. (Hank Walker/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

Law 116, which allowed sterilization surgeries, was passed in Puerto Rico in 1937. Health workers visited many family homes and pushed mothers to undergo hysterectomies or tubal ligations. In 1953, 17% were sterilized. In 1975, 35% were sterilized and the average age at the time of the operation was 26 years old. These surgeries were so common that they were simply called La Operación or “The Operation.” Many of these women were uninformed that these surgeries meant they would become permanently infertile and were under the impression that the inability to reproduce was temporary.

Puerto Rico was used as a laboratory by U.S. eugenicist Clarence Gamble, who tested contraceptives that were not approved by the FDA on over a thousand Puerto Rican women. The popular birth control pill we know today was tested on Puerto Rican women with the encouragement and help of Gamble. The women were informed that the drugs given to them were used to prevent pregnancy, but had no idea that they were test subjects. There were women who were severely sick, and women that died. It didn’t matter if these experiments caused irreversible damage to their bodies – they were disposable in the eyes of eugenicists. It did not matter because upper-class white women, who were the first main consumers of the pill, were able to advance their mobility.

Eventually, the trials and experiments ended. But by the end of the 1970s, one-third of all Puerto Rican women were sterilized.

The denial of reproductive freedom and autonomy has been orchestrated beyond the overturning of Roe v. Wade. This is just one of the plethora of examples of a marginalized group being denied reproductive freedom and autonomy.

James Baldwin once said “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” History also isn’t a series of isolated events. Everything is connected — Law 116 and the fall of Roe v. Wade are violent demonstrations of bodies being denied autonomy. They also involve, albeit in different ways, white people elevating themselves and their power.

The first step toward whiteness being decentered in the fight for reproductive justice and implementing intersectionality in praxis and discourse is to listen to different voices from different marginalized groups. Bring women of color to the front, burn the table that allows white supremacy to flourish, and work toward building a new, more inclusive table. It’s not going to solve everything. But it’s a start.

If you would like to learn more about the dark history of sterilization in Puerto Rico, below are a few sources I recommend and where I got my information from:

Matters of Choice: Puerto Rican Women’s Struggle for Reproductive Freedom by Iris Lopez

La Operación (1982) directed by Ana Maria Garcia

Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico by Laura Briggs

Needing To Abort Due To a Life-Limiting Fetal Diagnosis Was Heartbreaking Enough Already

Torre hadn’t always wanted to have kids — she was, after all, once a ‘90s punk rock teen who believed procreation was a self-serving planet-destroying impulse — but she began feeling the pull to parent in her 20s, and by her late 30s, her biological clock was ticking hard. Still, she didn’t feel financially or emotionally ready to parent alone. But then she met Oshin — they were a customer at the bougie pet store in Portland where Torre worked — fell in love, moved in together during the pandemic, realized they both wanted to be parents, and began the arduous process that is Trying to Conceive as a Queer Person. There were fertility drugs and a difficult and expensive search for a sperm donor who was, like Oshin, Armenian; and concerns that at the age of 40, it’d be difficult to conceive. But after four rounds of IUI, Torre and Oshin got the good news in December of 2021: They were pregnant!

“I was shocked and in disbelief but oh so happy,” Torre remembers. She was with her family in Denver when she got the news, and immediately told her Mom and sister. They decided to nickname the baby ‘Angelfish,’ an idea that’d come to Torre’s Mom in a dream she’d had about her daughter being pregnant a few years prior. By the time they made their pregnancy announcement on social media at 12 weeks, most of Torre’s close friends already knew.

Oshin and Torre with their first Ultrasound picture. Photograph by Kael Tarog

“The room felt like it was shrinking.”

Three days after making that announcement, Torre and Oshin were beaming, expectant parents at a doctor’s appointment. Their sonographer had just taken an ultrasound, and they were taking pictures of it and sending it to their friends along with recordings of their baby’s heartbeat when the doctor entered the room and began: “Unfortunately…”

“My heart started pounding, I could barely hear what she was saying,” Torre recalls. “Something about the nuchal translucency being the wrong measurement. The room felt like it was shrinking. I tried to keep breathing. Oshin gripped my hand.”

The doctor explained there was a good chance the baby had chromosomal issues, and they could wait it out or do additional testing. They opted for a blood test and a chorionic villus sampling (CVS) biopsy, a prenatal test that takes a tissue sample from the tissue that will become the placenta.

Trisomy 18, or Edwards Syndrome, occurs in around 1 out of every 2,500 pregnancies and is caused by an error that happens during sperm or egg formation. Abnormal chromosome segregation (division of DNA) during formation of sperm or egg leads to a sperm or egg with two copies of chromosome 18 instead of one, thus creating an embryo with three copies of that chromosome. It’s a random and unpredictable event that a parent can’t cause or control, but chromosomal abnormalities are more likely to occur in parents of advanced age.

95% of trisomy 18 fetuses don’t survive full term. Genetically abnormal pregnancies typically end in early miscarriage, and of those that are diagnosed later in pregnancy in utero — typically around 12 weeks — 85% will not survive and instead will lead to a later miscarriage, intrauterine demise, or a stillborn birth. Of those who make it to delivery, only 50% survive two weeks, and under 5-10% survive past their first year.

But living with trisomy 18 isn’t easy, as it causes severe abnormalities in nearly every organ system. Children born with trisomy 18 generally struggle to breathe or eat and typically present with severe heart, gastrointestinal, and neurological defects, as well as significant developmental delays.

Rarely, doctors may offer potentially life-extending treatments like cardiac surgery to trisomy 18 babies, but infants with trisomy 18 are less likely than other babies to survive these surgeries. Because of the degree of lethality, most doctors recommend no intensive intervention and only supportive comfort care for infants born with trisomy 18.

After consulting with their medical team, Torre and Oshin chose to terminate the pregnancy. “As gut wrenching as it was, we felt that the least suffering for our Angelfish, Oshin, and me would come from saying goodbye,” she remembers.

After waiting a week due to pandemic staffing shortages, Torre had a fully sedated dilation and evacuation (D&E) at 15 weeks. “I woke up feeling deeply changed, to my core,” Torre says. “This type of grief is so intangible and crazy-making.” She felt blessed to have such a supportive partner and community. Her doctor provided resources, she saw a counselor, and her mother flew out to help her in the immediate aftermath.

The mantle shrine to Angelfish. “I have no recollection of taking it, but it’s from my phone,” Torre says of the photo. “It was all such a dark blur.”

When Your Only Option Is No Option At All

Choosing to terminate a planned pregnancy due to a life-limiting fetal diagnosis isn’t easy, especially for queer families or others struggling with infertility who have put significant financial resources and time into the process. But following the overturning of Roe v. Wade, termination won’t be an option at all for many parents and may impact whether parents in those states even try to conceive at all.

While the conversation around abortion rights tends to focus on unwanted pregnancies and those that pose a threat to the mother’s physical health, life-limiting diagnoses are a less-discussed reason a parent may require abortion care — and may need to do so later in their pregnancy.

Even before the Supreme Court’s devastating decision in June of 2022, it was already difficult-to-impossible for many people to terminate pregnancies due to “incompatible with life” prognoses for the fetus — it’s expensive, rarely covered by insurance, and already required travel and jumping through multiple hoops for those living in areas with heavily restricted abortions. In some states, doctors are prohibited from informing their patients that termination is an option, leaving parents to simply wait for what will likely be a miscarriage or stillbirth, while others will do their own research and elect to travel out-of-state to receive an abortion.

“It’s traumatic enough to have to end your baby’s life,” writes Kelcey of her trisomy 18 baby on Shout Your Abortion. “I still felt guilt and shame for the choice that I made. Having to go out of state and stay in a strange place, having so little support and the stigma attached made it so much worse.”

“Carrying a pregnancy for weeks knowing it’s not viable and needs to be terminated is brutal.”

Confirming a life-limiting fetal diagnosis — defined as “lethal fetal conditions as well as others for which there is little to no prospect of long-term ex utero survival without severe morbidity or extremely poor quality of life, and for which there is no cure,” which includes a multitude of cardiac defects as well as trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 (Patau Syndrome) — can take time.

The first diagnostic tests are available at 10-13 weeks, and confirmatory tests and results can take a few more. The worst case scenario is one in which a parent lacks insurance coverage for genetic testing and can’t afford the out-of-pocket fee and therefore doesn’t get a diagnosis until their 20-week ultrasound — but any scenario will put many parents in a terrifying time crunch, depending on their home state’s specific restrictions. Abortion providers in states like New Mexico, on the border with Texas, are already seeing incredibly long wait times for appointments, if a parent is able to get an appointment at all.

“Abortions are safer the earlier they happen in a pregnancy,” Dr. Elizabeth Rubin, a board-certified OB/GYN in Oregon who was one of Torre’s doctors, explained to me. “So what they’re doing is taking someone who already has a heartbreaking diagnosis, already is going through hell, and slapping an extra dose of unsafe onto it — adding unnecessary time pressure, schedule/travel stress, shaming and morbidity to a safe procedure — and adding to their recovery time. And honestly, really f*cking with their mental health.”

Another hopeful mother on SYA shares a story where, despite living in California; due to limited options from her local Catholic-controlled healthcare system and a totally-booked Planned Parenthood, wasn’t able to terminate her trisomy 18 baby until just shy of 22 weeks, after a friend of a friend called in a favor to the dean of her local medical school. “Carrying a pregnancy for weeks knowing it’s not viable and needs to be terminated is brutal,” she writes. “In those weeks I had no choice, I didn’t have the healthcare I needed.”

If forced to endure an excessive wait time or unable to abort at all, parents will likely miscarry. “It sucks to get the option of a D+E under controlled circumstances taken away from you,” Dr. Rubin explained, “and instead you have a miscarriage at home in your bathroom and then have to go to the hospital and have a D+C for the placenta. Like, that sucks! And it doesn’t have to be that way! That can be predicted and avoided.”

“Patients deserve the chance to know their options.”

When such a condition is diagnosed, doctors are advised to engage in Perinatal Palliative Consultation, a care strategy that focuses on “ameliorating suffering and honoring patient values,” presenting options including either terminating the pregnancy or continuing with it and then developing a post-birth care plan where one must choose priorities such as life prolongation or comfort.

“One of the most important parts of medicine, especially in gynecology, is shared decision-making,” Dr. Rubin told me. “Patients deserve the chance to know their options and think them through — that’s actually part of the grieving process.”

“I’ve seen families who have said, I love my child and want to do everything I can to help her live,” doctor Thomas Collins told Stanford Medicine, “and other, similar families who love their kids just as much who have said ‘In our family that is not living; it’s torture.’”

“We could not protect our daughter from trisomy 18, but we could shield her from any pain or agony that would come with it,” wrote Allison Chang, a then-medical student at Harvard, in an essay about her trisomy 18 experience. Chang recalled her relatively humane, while still traumatizing, experience terminating her pregnancy in Massachusetts, compared to what her friend endured in Missouri, which included a hefty price tag and being “vaguely awake” during the procedure.

Different Choices for Different Parents

For “pro-life” parents, the path forward is clear-cut in a different direction. “We decided that if our son’s death was impending, we would not be the one to set that date,” writes the founder of Abel Speaks, a non-profit providing support for parents who’ve chosen to carry a child with a life-limiting diagnosis, in a video about the organization. “While losing Abel was tragic, the real tragedy would’ve been if we’d kept ourselves from truly loving Abel during the time when we did have him.”

Organizations and Instagram accounts like Abel Speaks emphasize that God has a plan for every life and that life doesn’t need to be long to have value. Their social media feeds solicit prayers for the passing of tiny humans who lived briefly and for pregnant couples (somehow exclusively photographed in grassy meadows) to have safe and smooth deliveries and a chance to meet their baby alive. They’re confident not only in God’s plan but in the existence of heaven and God’s readiness to accept and cherish their infant after its imminent passing. Many want the chance to Baptize their baby before the end of its life.

Abel Speaks is a window into a culture with very different values than my own and a religion very different from my own (I’m Jewish). Still, I can understand their perspective and appreciate their right to make decisions in accordance with their values. I’d even say that reading their stories did open my mind to another way of approaching a diagnosis like this, although it wouldn’t change the decision I’d make in their shoes, and I don’t think their religious or cultural beliefs should impact what choices are available to me or other parents with life-limiting fetal diagnosis.

That said, it’s not only religious and anti-choice parents who choose to keep a baby with a life-limiting diagnosis; some parents may choose to continue the pregnancy for other reasons, like that they feel they’ll have more closure being able to hold their baby than they would after a D&E. That, too, should be a choice, Dr. Rubin echoed: “Even for patients who decide they want to carry the pregnancy for as long as it lasts, or deliver, knowing that a doctor thinks an abortion is a reasonable alternative is important,” Dr. Rubin told me. “It also helps them to understand the gravity of the disease and their blamelessness, that this is not their fault.”

In this way, the life-limiting diagnosis debate illuminates precisely why choice is so important: Different parents have different values, priorities, and circumstances that lead them to make different decisions.

Pregnant people who don’t need to work may have more room in their lives for a pregnancy with such a difficult prognosis than those who need to be more pragmatic about their time off. People over 40 trying for their first child may know that termination is actually the option more likely to enable them to have a healthy baby, whereas a younger pregnant person might not feel that urgency. Parents who’ve already endured the trauma of a stillbirth may be more inclined to do what they can to prevent another.

The “best case scenario” for a child with trisomy 18 — living past that first year or longer, as famously has been true for Rick Santorum’s daughter Bella — is often still untenable for parents who, in a country starved of social services and health care, don’t have the time, financial resources, or health insurance to support a child who requires full-time care, or who already have children with special needs.

Instagram accounts like TFMR (terminating for medical reasons) Mamas offer support and visibility to parents who’ve had to terminate for a medical reason, who often feel ostracized from spaces for grieving a baby loss. This May, they held the first ever TFMR Awareness Day. Just over a month later, they were, posting in response to the Roe v. Wade overturning: “Having to navigate unnecessary barriers to the essential care that we need at this time creates so much extra distress on top of the unbearable heartbreak that TFMR parents are already trying to cope with… You don’t deserve this, our future TFMR parents don’t deserve this, I’m so sorry this is happening in 2022!”

“Since Roe v Wade was overturned I have been cycling through my own experience and just can’t fathom what it would have been like if, on top of our absolutely heart-crushing situation, I then had to worry about legalities and having to travel to have my procedure done,” Torre says. “I am really lucky to be living in a state where my right to an abortion is protected. Going back into trying again is already nerve-wracking, let alone having to worry about what I would do, or be allowed to do, if something goes wrong in future pregnancies.”

For patients pursuing fertility in states where abortion isn’t available, they will have to make a plan ahead of time for the possibility of a life-limiting diagnosis. This could mean paying out-of-pocket for a Cell-Free DNA screening earlier in pregnancy or even electing (the much more expensive option of) IVF rather than IUI because preimplantation genetic testing can examine the embryos prior to transfer for a range of genetic problems.

“These laws weren’t written by doctors, so they’re not written in ways that actually reflect medicine,” Dr. Rubin told me. “No one’s saying we could list the situations in which, say, a neurosurgeon could operate. Whomst amongst us could say we understand neurosurgery well enough to write legislation that determines when you can operate on a spine or a brain tumor? But because this involves pregnancy, they somehow think this should be something that everybody gets to weigh in on? And that lawmakers understand, even though they’re not doctors? There’s nothing I can think of in medicine quite like this.”

I’m Trans, I’m Trying to Get Pregnant and I’m More Pro-Choice Than Ever

I’m in what’s called the TWW — the two week waiting period between insemination and a missed period, or a period that comes and dashes all your hopes that the insemination worked. I’m texting with my friend about whether or not I have the strength to endure the disappointment of a negative pregnancy test next week, whether or not I can maintain hope through what may be many insemination attempts. Then she texts me, “Fuck.”

Roe v. Wade has been overturned, today, as I lie here praying that I’m pregnant. And I have never been more pro-choice than I am in this moment.

I was raised to protest abortion, to pray outside of abortion clinics, to look forward to and celebrate this day. My two BFFs in high school were related to a man who shot an abortion doctor for Jesus, which they thought was probably okay. Now I’m a leftist adult trans person who had no qualms about leaving ‘Merica behind to live with my soulmate in her country, Canada, which has federally socialized healthcare, including abortion care.

I have a history of sexual abuse and sexual trauma perpetuated by cis-het men. Sticking a syringe inside myself and injecting sperm is not something I enjoy. But I want a baby, and I’m doing it my own way — in an Airbnb with my wife by my side. There’s historical evidence of widespread abortion and contraception advocacy across the world, and the knowledge developed by people who were trying to avoid pregnancy is the very knowledge my partner and I are using to get pregnant: tracking ovulation, using cervical cups, etc. Undergoing this process has shown me just how absurd anti-abortion rhetoric truly is.

I have to confess that as a masculine person who has never had voluntary sex with cis men and who can’t get someone else pregnant, I hadn’t thought about abortion as much as I should have until recently. I have a uterus, which means I could be assaulted and could get pregnant against my will. Still, I thought, conversations about abortion didn’t really apply to me. I listened to the women I knew who’d had abortions (most of my partners, many of my friends and nearly every feminist thinker I’d learned from). When I lived in the US, I marched and voted and organized and signed up to drive people from rural areas to abortion clinics in Pittsburgh. And still, I didn’t think I would ever have to make a choice about having an abortion myself — until I decided to try and carry a child.

Before we started the fertility process, my wife and I had a conversation about whether or not, or when, we might have to make this choice. At 37, bearded and without tits, I finally weighed it out for myself. My wife and I agreed that we will probably opt for abortion in certain cases — for example, if the fetus has anencephaly. That’s when the skull and brain of the fetus do not grow and there is literally no hope that the baby will live beyond a few days after birth, if that, unconscious and in physical pain.

Since insemination, I’ve been nauseated every day, I’ve been disgusted by coffee (one of my favorite things) and salt (ditto), I’ve broken out with pimples in new places and I’ve been moody and emotional AF without my cannabis. Yet I walk around my neighborhood, I go to the store, I do all my normal activities — and no one else can tell. No one is passing me on the street saying, “Oh wow, there’s two of you now! There’s a person inside you!” Because even though I want to make a person with all of my heart, I am keenly aware that what’s happening inside me is a long and complicated process; there’s no magical instance when suddenly there’s an autonomous, separate human inside me.

The “pro-life” movement, codified by conservative Republicans, uses terms like “holocaust” and “genocide” to describe abortions, though they are politically aligned with literal holocaust deniers, rapists, child molesters, cops, border patrol agents and racists who participate in the continual genocide, oppression and sometimes even forced sterilization of marginalized people on this continent — especially BIPOC. The irony is intense.

I’m from a Catholic background similar to the culture that produced Amy Coney Barrett, although not as economically elite as the culture that produced Bret Kavanaugh. I can attest that the overturn of Roe v. Wade is a high holy day in their worlds. But while Catholics have been some of the key authors of anti-choice rhetoric, a 2014 study by the Guttmacher Institute found that Catholics have more abortions than Protestants, and Christians have more abortions than most other religiously-affiliated folks. Rich, white Christians and conservatives (and especially their mistresses) will continue to have safe abortion access in many instances, even if they have to cross state lines or fly out of the country to get one.

While Republican-appointed Supreme Court Justices are stripping people in the US of abortion rights, conservatives all over the world are coming for trans people, especially trans kids who have the courage to come out and ask for what they need. They’re making rules about when we can access the healthcare we need to survive, to grow up, to live our lives. While FINA has declared that swimmers must fully transition by twelve to be eligible to compete, parents in some states are being criminalized for allowing their children to get transgender health services if they are younger than eighteen.

When I moved to Canada and could get top surgery without a million consults or a letter from a psychiatrist — and at a fraction of the cost it would be in the US — I got a taste of what it feels like to have bodily autonomy. This sense of autonomy has enabled me to envision being pregnant. Without being able to assert my masculinity by coming out, letting my goatee grow and having top surgery, I would never have been able to imagine doing such a “feminine” thing as getting pregnant. According to the religious right, producing another human person is the most important thing I could ever do. Yet without actual bodily autonomy — including the right to have an abortion — I could never have started this process.

In the same way the Supreme Court is now saying that people with uteruses should be forced to carry fetuses to term, those who prevent trans kids and teens from accessing transition-related care are also forcing people to live in bodies that are not their own. When a country limits the individual’s autonomy over their own body, that is an assault on the people who live in that country — not just on the people with uteruses, but an assault on everyone.

Medication Abortion 101

Today is a heavy and unprecedented day. Whatever you are feeling today is valid and I hope you allow yourself space to take care of yourself this weekend. My “day job” is working as a campaigner at a gender justice advocacy organization where we have been prepping for this moment for months and preparing to fight back and identify opportunities to help those most impacted. In my “day job,” I focus on fighting online disinformation and misogyny online and I’ve learned that one of the best ways to fight false information is through sharing the truth.So I’m here to provide a small ray of hope and accurate medical information (though I am not a doctor, just a reproductive rights activist) about medication abortion.

Medication abortion is safe, effective and fully FDA approved and it can be accessed by mail, which means it will remain an option in states that now ban or even criminalize abortion, albeit with some risk attached in the states where it is criminalized. Here is everything I know about medication abortion so that you can access the care you need, share it with a friend, or save it for that just-in-case moment.

What Is Medication Abortion?

Medication abortion is a non-invasive combination of two medications, Mifepristone and Misoprostol, that work together to end an early pregnancy. It is FDA approved for the first 10 weeks of pregnancy but some providers will prescribe it off-label later in pregnancy.

It has a 95% success rate, and less than 0.5% of patients experience serious complications. Most abortions in the United States are already done through medication abortion and that number is likely to continue rising.

How Does Medication Abortion Work?

Mifepristone stops pregnancy growth by blocking the hormone progesterone. Progesterone helps the uterus grow in early pregnancy and keeps it from contracting so Mifepristone helps counter these effects. Misoprostol, taken at a later time, makes the uterus contract. Patients take Mifepristone to start the process followed by Misoprostol one or two days later.

Is This the Same as Plan B?

No, Plan B is over-the-counter emergency contraception that helps stop a pregnancy before it takes hold, medication abortion is a prescription regimen of multiple pills to stop an early pregnancy.

Is Medication Abortion Safe?

Yes, Mifepristone and Misoprostol have a long record of safe use. They have been approved by the FDA for more than 20 years and have been approved in France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom since at least the early 1990s. Mifepristone actually has a better safety record than penicillin, Viagra, and even Tylenol.

These medications are also regularly used to treat other medical conditions. Mifepristone can treat high blood sugar in people with Cushing’s Syndrome and Misoprostol helps prevent stomach ulcers.

What’s the Legal Situation Now?

In this new post-Roe world, things are unfortunately complicated but that’s not to say there aren’t options.

In 2021, the FDA removed the requirement for Misoprostol to be given in person in a medical setting and made it so that patients could access it via mail. Of course, that means in reaction, a bunch of laws were passed placing unnecessary restrictions and hoops in the way of accessing what should be a straightforward FDA-approved prescription. Today’s ruling complicated things even further; it means there are now many states with abortion bans and a few states where abortion is criminalized.

Thankfully, there are a few reliable websites (see below) that have done all of the research and have state-by-state information on how to access these pills within the legal confines of your state. In some places that may mean delving into legal grey areas, like using mail forwarding. I am not a lawyer and I’m not recommending you do something that will get you into legal trouble but as Mahatma Gandhi wrote in Non-violence in Peace and War “An unjust law is itself a species of violence.”

How Can I Access It?

There are a few websites you can try and see what has the best options for you in your state. I am a particular fan of Plan C because it lists resources and options available in places like Texas and Oklahoma, including things like getting a prescriber in the Netherlands and using mail forwarding.

What Should I Expect if I Take It?

According to Planned Parenthood the second medication, Misoprostol will likely cause fatigue for a few days, tender breasts if you have breasts, chills, fever, and nausea and you can expect to experience cramping and bleeding.

Can I Stock Up and Save It Just in Case?

In theory, these two medications are shelf-stable and could be acquired now and saved for a few years for a moment of need and it’s likely this will become a more popular, underground option. Again, I’m not a lawyer or a doctor so I can’t tell you how to make that decision. I can tell you that you will need a prescriber to get the medication in the first place and that Mifepristone has a shelf life of five years and Misoprostol has a shelf life of two years.

I Heard You Can Reverse It Is That True?

Abortion reversal refers to an experimental and dangerous procedure that has been promoted by anti-choice activists and physicians. They claim that by taking a large amount of progesterone — the hormones that Mifepristone blocks — and skipping the Misoprostol, it is possible to “reverse” an abortion.

There has only been one medical study ever attempted on this process and it was stopped early because it was deemed too unsafe to continue. Three people in the study were sent to the emergency room because of dangerous hemorrhaging. Both the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have denounced medication abortion reversal.

89 Abortion Funds That You Can Give To Immediately

Feature image by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

Today, I am numb.

I haven’t been able to wrap my head around today’s Supreme Court ruling without a fresh wave of nausea. We all knew it was coming, right? We knew back in May when an early leaked draft of today’s decision first circulated. We knew in the years before that. We knew that the end game has always been Roe v. Wade.

It was always coming, and today was the day.

In today’s decision to the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — which is about a Mississippi law banning abortion at 15 weeks — in unambiguous language, and a 6-3 majority vote, the Court overturned Roe, as well as another case, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which upheld the central tenet of Roe but allowed states to restrict access as long as they did not place “an undue burden” on people seeking abortions. From the decision, “We therefore hold that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion. Roe and Casey must be overruled, and the authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their elected representatives.” (You can read a full annotated version of the decision yourself.)

What comes next is overwhelming and can feel impossible. But what I do know is this — the fight is not done. It can’t be. 50 years ago we were promised a legal right our bodies and a group of extremists made it their life’s work to have that right taken back away. But if they can dedicate their lives to undoing the work of Roe, then I can surely dedicate mine to making sure those rights become enshrined, protected, and never taken away again.

I wanted to highlight at least one very specific, actionable thing you can do right now.

This post was originally written in 2021 and has been updated and republished twice this year, including today, because there is no way off this rollercoaster except to rely on ourselves, our advocacy, bear down and to fight.

What Is an Abortion Fund?

Over the last few months, you’ve probably seen calls to support abortion funds, and you’ll probably see more in the days and months to come. They provide financial and/or material (transportation, mental health care, volunteer assistance, etc) support to those who need an abortion. They’ve been around for decades. For those most vulnerable who need immediate aid now, and this is tangible way to show up and support.

You can donate (or learn how to volunteer!) with the organizations listed below.

As of today, right now, in about half of the states in the U.S., abortion has become severely restricted or outlawed. I have put an [*] next to states where abortions are restricted, likely to become prohibited, or where the future of abortion restrictions is uncertain in the days and weeks to come. I have put an an [**] next to states where, as of this writing, abortions are already banned. This comes from New York Times reporting, and as they update their states list, I will also update ours.

The purpose of this system is to draw attention to the inequity in safe abortion access in this country, and who is left with the least amount of resources available in light of today’s decision (and for many people, long before that, too). If you live in one of the 21 states, and DC, where the right to abortion is legally protected — recognize your privilege, and support beyond the guaranteed safety net your community.

Give to an Abortion Fund Today

Some of these funds have “women” in their title. Not all people who are in need of abortions are women. However, in the interest of providing the widest breadth of information to those who may be in need, in parts of the country where access is in immediate jeopardy, we only included funds that have “women” in the title if there was no other fund available in that state. We recognize it’s a delicate line, and one not one we take lightly. Safe abortion access is critical for trans patients, and should always be a priority.

Alaska

Alabama *

Arizona *

Abortion Fund of Arizona

Tucson Abortion Support Collective

Donate to Multiple Arizona Funds at Once, including Indigenous Women Rising (Arizona)

Arkansas *

California

Colorado

Cobalt Fund

Colorado Doula Project

Colorado Organization for Latina Opportunity and Reproductive Rights

District of Columbia

Delaware

Florida *

Florida Access Network

Emergency Medical Assistance Inc.

Tampa Bay Abortion Fund

ARC — Southeast

Donate to Multiple Florida Abortion Funds at Once

Georgia *

ARC — Southeast

The Feminist Center (Atlanta)

Hawaii

Idaho *

Illinois

Indiana *

Iowa *

Kansas *

Kentucky **

Louisiana **

Maine

Massachusetts

Abortion Rights Fund of Western Massachusetts

Eastern Massachusetts Abortion Fund

Jane Fund of Central Massachusetts

Maryland

Michigan *

Minnesota

HOTDISH Militia (Hand Over The Decision It’s Healthcare)

Our Justice’s Abortion Assistance Fund

Just the Pill

Mississippi *

Missouri **

Montana *

Nebraska *

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina *

North Dakota *

Ohio *

Oklahoma **

Oregon

Pennsylvania *

Rhode Island

South Carolina *

South Dakota **

Tennessee *

Texas *

The Afiya CenterThe Bridge Collective

The Clinic Access Support Network

Frontera Fund

Fund Texas Choice

Jane’s Due Process

Lilith Fund

Texas Equal Access Fund

West Fund

Utah **

Vermont

Virginia *

Blue Ridge Abortion Fund

DC Abortion Fund – VA

New River Abortion Access Fund

Richmond Reproductive Freedom Project

Hampton Roads Reproductive Justice League

Washington

West Virginia *

Wisconsin *

Wyoming *

We Will Protect Each Other: A Queer Feelings Atrium After the Fall of Roe

Ya’ll.

Maybe you knew it was coming. Maybe you were completely surprised. Regardless, no one wanted to tune in this morning to find that the Supreme Court of the United States had not just gutted but completely overturned Roe v. Wade. The court upheld the Mississippi abortion ban and overturned both Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. This turns the governance of abortion back to the states in the U.S.; in about half of the states in the U.S., abortion will become severely restricted or outlawed.

Fuck.

Shit.

I don’t have more eloquent words at the moment. Nor the time or brain power to go deeper on what this all means. Maybe you do. In the style of an old school feelings atrium, I’m here to talk today and to facilitate our community talking with each other. If you’re feeling a way – enraged, anxious, in mourning, nostalgic, fired up, like you need to scream into a void–this is a space to express that as well as anything else you need to get off your chest.

One thing I know for certain, we will protect each other. We’re here for each other.

So, how are you doing? What are you thinking? What do you need? I’ll meet you in the comments.

The Fall of Roe Is For All Of Us

Feature image art: Autostraddle, photo: Alex Wong/Getty Image

I was buying a vegan chickn wrap at a walk-up eatery near Syracuse University in 2006 when the cashier said, “I like your shirt!” The shirt was a black fitted tee with bright pink graphic lettering that read, “SAVE ROE!”

I was a professional campus organizer for a local affiliate of Planned Parenthood, and barely out of college myself. This was before the federal abortion ban and way before the current case before the Supreme Court and my work was primarily around expanding and protecting access to contraception.

Abortion bans and hostile restrictions were constantly on and off the table at the federal level, and there was a definite sense of anti-abortion extremists trying to chip away at the protections of the Roe v. Wade decision, but the idea that Roe would actually be overturned felt distant and vague and hyperbolic to a 23-year-old who had grown up in a post-Roe generation. I wore the shirt as a reminder to others of how important and how often fragile abortion rights were overall, not as a serious warning that Roe v. Wade might be gone in my lifetime.

Fast forward to Monday night, when I was checking slack for Met Gala hot takes after putting my five-year-old daughter, Remi, to bed and saw that my workplace chat was blowing up. Those of us closely following the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (JWHO) case have known for months now that it’s extremely likely we’re on the precipice of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) overturning Roe v. Wade. Abortion rights groups and repro justice groups and health providers and abortion funds have been planning and strategizing how to respond when that decision comes down later this year — likely in late June or early July. Working on everything from policy reform to creating community-based pathways to legal abortion when it becomes outlawed in almost half of the US.

Still, it felt like there was some bit of hope or at the very least, that it wasn’t yet a concrete reality yet, like maybe we could salvage something. In other words, the fact that SCOTUS was hearing this case meant they were open to reopening the decision on abortion, which was extremely alarming, but we were holding out hope that it was possible they wouldn’t fully outlaw abortion. We are still holding out hope — this isn’t over yet! But we need to move as if Roe is truly in peril, because it is.

On Monday night, a draft of Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion on the JWHO case was leaked to the press and it is… in a word… terrible. Terrible for abortion rights and access. Terrible for queer and trans people. Terrible for Black and brown people. Terrible for disabled people. Terrible for rural poor people. Terrible for Indigenous people. Terrible for immigrants without papers. Terrible. Terrible for all of us.

For the first time in my life, I’m absolutely certain that the conservative right is going to do everything they can to strip away the protections of the landmark Roe case. They’ve been trying to for decades, since Roe became the law of the land in 1973. That’s not new. But this is the first time I believe they may have the political power to do so, despite the fact that the majority of people in the U.S. regardless of which political party they belong to are supportive of legal abortion.

There’s a lot of confusion going around about what this all means and as someone who worked in repro and/or civil liberties work for over fifteen years, I’m here to demystify the moment we’re in right now. I’m not an attorney, but I used to play one on TV, so let me fill you in on what’s going on and what the potential end of Roe means for us.

Is abortion still legal?

Yes, abortion is still legal! Very much so. Despite some misleading headlines, SCOTUS has not voted on Dobbs v. JWHO yet.

The leaked opinion shows a clear intention for the currently presiding conservative majority to vote to overturn Roe, but it hasn’t actually happened yet. In fact, if you or anyone needs an abortion, you can find a provider at ineedanA.com or by texting “hello” to 202 883 4620.

Will abortion be legal if Roe is overturned?

Even if the JWHO vote happens and it results in a full repeal of federal abortion rights, some states will still have safe, legal abortion. Some states have trigger laws, state laws already on the books that ban or restrict abortion in the state. As long as Roe is standing, the federal protections for abortion mean that the state laws that conflict with Roe can’t be constitutionally enforced. If Roe is no longer the law and there is not sufficient federal law (which there currently isn’t), abortion bans or restrictions in those states will be able to go into effect and possibly be expanded. From the Guttmacher Institute:

“If Roe were overturned or fundamentally weakened, 22 states have laws or constitutional amendments already in place that would make them certain to attempt to ban abortion as quickly as possible. Anti-abortion policymakers in several of these states have also indicated that they will introduce legislation modeled after the Texas six-week abortion ban.

By the time the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in the Mississippi case, there will be nine states in this group with an abortion ban still on the books from before Roe v. Wade, 13 states with a trigger ban tied to Roe being overturned, five states with a near-total abortion ban enacted after Roe, 11 states with a six-week ban that is not in effect and one state (Texas) with a six-week ban that is in effect, one state with an eight-week ban that is not in effect and four states whose constitutions specifically bar a right to abortion. Some states have multiple types of bans in place.”

Why is this leaked opinion important?

The SCOTUS justices, while holding an appointed position and not an elected one, tend to correspond along Republican and Democratic lines, based on the party under which each justice is appointed. We tend to think of justices as either conservative, liberal, or moderate based on their voting records and backgrounds. Right now, three of the nine judges are decidedly conservative, and three are decidedly liberal. There are technically four moderates, but they were all appointed under a Republican administration.

There is and was some hope that the more moderate judges wouldn’t vote for a full repeal of Roe v. Wade, as there’s a possible outcome here that the vote is split on the question of a radical move like a full repeal. Instead, the decision could be made to more narrowly rule on the Mississippi law in question in the Dobbs v. JWHO case, likely voting to uphold the Mississippi law limiting abortion to fifteen weeks.

However, in the recent Texas case, which effectively eliminated abortion in Texas by criminalizing abortions after six weeks, Justice John Roberts voted with the liberal judges. Roberts is no pro-choice champion, to be clear and he has voted against abortion rights in the past. He represents a view that more strictly interprets the role of SCOTUS to not move quickly to divisive rulings or rulings that interfere with established precedent. He is also the chief justice, but other more moderate judges did not join him in taking a moderate approach on abortion in the recent Texas case, thus upholding Texas’ SB8 in a 5-4 vote. Two justices considered moderate (not in my opinion, but in general opinion), Kavanaugh and Barret, have both expressed an interest in overturning Roe, which means moving towards the middle to join Roberts seems unlikely.

So we come to a place of assuming Justice Alito, who is deeply conservative, is representing the majority opinion because we’ve been anticipating for quite a while that this court is hostile to abortion rights. The opinion itself is damning, not just for the end of Roe v. Wade, but the right to privacy established by several landmark SCOTUS cases including Roe v. Wade. It’s true that drafts of the majority and minority opinions are often worked on before the decision day, especially when it’s known or assumed what the outcome of the vote will be, so it’s possible this isn’t final. It has been confirmed as authentic, though, and it gives us a lot to worry about.

What are we worried about?

So many things. If we lose Roe, abortion will be banned in many states, making it much harder to access safe and legal abortions. People will need to travel thousands of miles depending on where they live. Many will be unable to afford that, and criminalizing abortion doesn’t mean abortions won’t happen. Abortion rates are not slowed when abortion is not legally available. Historically, we know that pregnant people will seek abortions regardless, but what should be an extremely safe and routine procedure becomes deadly when it’s criminalized. And those more impacted will be poor folks, Black and Latinx folks, young people, immigrants, and anyone without financial means to get on a plane and fly out to where abortions are still safe. Already, material mortality rates are significantly higher in states that have restrictions on abortion.

Beyond that, Roe v. Wade and reproductive rights, in general, are directly tied to establishing the constitutional right to privacy. That right is not enshrined in writing in the Constitution. It’s been established through legal precedents, like Griswold v. Connecticut, the case that first legalized birth control specifically for married couples in 1965, which established that there are “zones of privacy” inherent in the Constitution. Other repro cases like Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972 and Roe v. Wade in 1973 expanded on this idea of privacy from government intrusion, eventually extending that right to the individual. In the case of Roe, it created a specific link between the due process clause of the Constitution and the right to privacy.

The landmark LGBTQ case, Lawrence v. Texas, which overturned homophobic anti-sodomy laws in 2003, directly quoted Roe and other repro cases to make the argument that the government should not interfere in consensual, adult sexual behavior in the home. Privacy rights again came into play in Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 SCOTUS ruling that legalized marriage across the US. We should be worried about this and more. Forced sterilization laws, interracial marriage, access to contraception, rights of sexual assault survivors, rights of sex workers, are all things on the table if Roe is overturned.

That said, the jumping from what is happening now to, “They’re coming for gay marriage next!” is not rooted in a real threat, today, right now, and also inherently implies that the current issue before SCOTUS is not an LGBTQ issue. It absolutely is.

Why does this matter for queer and trans people, in particular?

Queer and trans people have abortions, for any number of reasons. We and our partners have abortions and are too often facing double stigma, stigma and shame around receiving abortion care and stigma (unfortunately often by service providers) for being trans and/or queer. Abortion is not a “women’s issue” and it’s not a cisgender heterosexual issue. It’s our issue and it affects our communities and it’s deeply under threat. We have to act, not just because we are afraid of losing other rights in the future, but because this is about us and our people, right now. If our feminism is intersectional and if our belief is that our community matters, we need to see abortion as a queer issue and trans issue right now.