Read these works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and then let yourself fill with rage and release.

Rage Party

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

Jun 24, 2023

lesbian sex

NSFW

lesbian sex

Try These Exercises for Better Strap-On Sex

Ro White

—

personality quiz

Rage Party

quizzes

Quiz: What’s Your Pride Vibe?

The Latest

Lgbt History

Mar 21, 2025

Television

Mar 21, 2025

Af+

Mar 21, 2025

Sports

Mar 21, 2025

Television

Mar 21, 2025

#affiliatemarketing

Rage Party

#affiliatemarketing

Rage Party

#affiliatemarketing

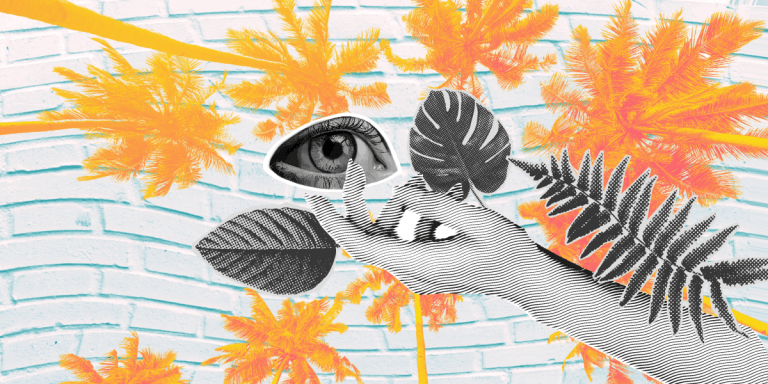

documentaries

Featured Archive

#affiliatemarketing

Rage Party

Rage Party

How a Far-Right Moms Group Is Threatening Queer Liberties in Schools

lesbian sex

NSFW

Try These Exercises for Better Strap-On Sex

Ro White

—

personality quiz

Rage Party

Quiz: What’s Your Pride Vibe?

#affiliatemarketing

Rage Party

In The Terrible We, Cameron Awkward-Rich Makes Space for Bad Trans Feelings

Guides

Sundance 2025

book lists

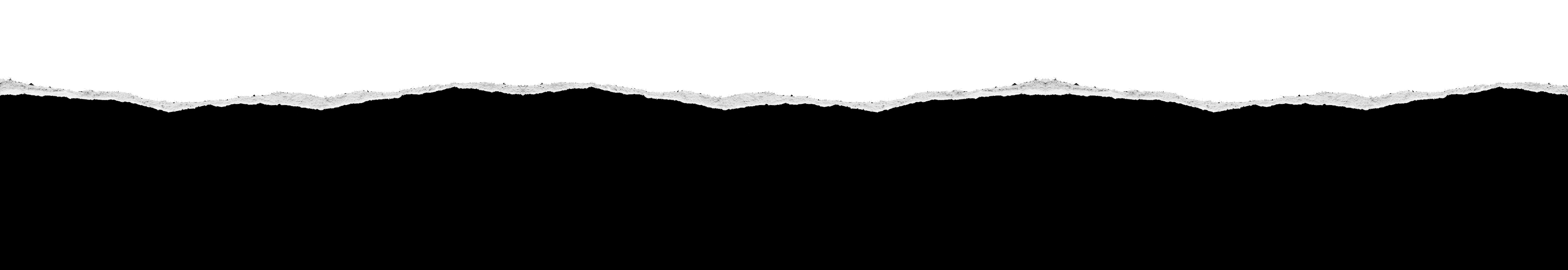

Tap Into Queer Rage This

Pride With These Scorching LGBTQ+ Books

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

Jun 24, 2023

Literature

Reviews

Literature

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

News

Rhea Almeida

Love + Sex

Ro White

Games

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

Recaps

News & Trailers

Queer Fashion

Become a Member

Become a Member to support queer journalism

What You Get:

LEARN MORE

Become a Member

Become a Member to support queer journalism

LEARN MORE

Fim & TV Features

Read these works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and then let yourself fill with rage and release.

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

Jun 24, 2023

lesbian sex

NSFW

lesbian sex

Try These Exercises for Better Strap-On Sex

Ro White

—

personality quiz

Rage Party

quizzes

Quiz: What’s Your Pride Vibe?

Lgbt History

Mar 21, 2025

Television

Mar 21, 2025

Af+

Mar 21, 2025

Sports

Mar 21, 2025

Television

Mar 21, 2025