Evolution’s Rainbow: Joan RoughGarden Explores Queer Sex in Animals

A few days ago a small cardboard box arrived, leaning precariously out of my mailbox. Now, this is somewhat of a common occurrence, because I have no sense of self-control when it comes to buying books. But this was no ordinary book — it was Joan Roughgarden’s Evolution’s Rainbow, which several of you commenters have mentioned before. Well, I finally got it, and I am so glad you all told me about it!

Roughgarden is a professor of biology at Stanford University, and author of several other books on the intersection of evolutionary biology and social mores. A transgender woman, she discusses how she kept her job at Stanford during her transition but had to relinquish many administrative duties; she used her newfound free time to research the diversity of gender and sex across species and cultures. She wrote Evolution’s Rainbow both as a catalogue of diversity across the natural world in sex, gender, and sexuality, and also as an “indictment” of all academic fields for suppressing or ignoring the diversity that we see.

The book features a sunfish on the front, a species which has four genders and is native around Roughgarden’s home town (via theguardian.com)

This is an incredible book. It’s a brick, yes, clocking in at 407 word-filled pages, but its text is accessible, well-written, and insightful. Every page or two elicited a ‘holy cow that’s so awesome!’ from me, and all of you — biologists and non-biologists and poets alike — you all should read it. In the meantime, while you wait for your own copy to arrive, I’ll try to summarize what I took away from the book — with the important caveat that I am no evolutionary biologist, or even a life scientist in general.

Her premise, as I see it, is that there are hundreds (or more) of species that don’t exhibit behaviors consistent with Darwinian sexual selection theory, suggesting that it is not the universal truth we take it to be. Further, our current insistence on sexual selection theory leads to incorrect conclusions as well as dangerous societal implications, which I’ll discuss more in a bit.

A little bit of background: Sexual selection theory states that the basic building blocks or templates for a species are male and female, and that each sex has built-in traits —the male is the assertive, passionate one, and the female is shyer and coyer. Males compete for the attention of females, and the female generally chooses the most successful-looking males to mate with, thus ensuring strong and successful offspring. Roughgarden writes:

“This theory [sexual selection theory] that social life boils down to a selection for showy traits is both inaccurate in its universalist claims and inadequate to address the diversity of bodies, gender expression, and sexuality that actually occurs in nature. Furthermore, the theory has been corrupted by evolutionary psychologists and others to naturalize injustice and deny freedom of expression.”

The author, Joan Roughgarden (via ai.eecs.umich.edu)

In a section entitled “Sexual Selection Corrupted,” Roughgarden argues that the problem with this general theory of reproduction, apart from the possibility that it is over-generalized and incorrect, is that it leads both to a disparaging of any member of a species that is not the “alpha-male” type, and that it naturalizes male aggression and domination of females. In modern times, a corrupted take on sexual selection has long been “used to perpetuate ethically dubious gender stereotypes that demean women and anyone else who doesn’t identify as a gender-normative heterosexual male.” I’m sure you’ve all heard of evolutionary psychology, and how it attempts to normalize aggressive and promiscuous sexual behavior in males, while consigning women to passivity and a lack of sexual assertiveness themselves. In its worst manifestations, evolutionary psychology asserts that rape is an evolutionarily inherited behavior by males: historically males who couldn’t find a mate in other ways could also reproduce through rape, and thus “rape genes” were passed from one generation to the next. It leads to the dubious conclusion that “all men are therefore potential rapists, although they do not necessarily act on this potential.”

Instead, Roughgarden advocates “social selection theory,” which emphasizes species-wide teamwork, not sex-based competition. In this theory, animals evolve traits that lead to inclusion in groups that can more effectively provide food, safety, and resources to successfully raise offspring. And all along the way, as she argues her point, she offers as evidence a wide array of diverse animal sexual behaviors to show that, contrary to common belief, sexual behavior does not adhere to any one norm.

This includes homosexual behavior in animals. She lists hundreds of species that engage in some level of homoerotic or homosexual behavior, from reindeer to African elephants to marmots and vampire bats. Almost all male bighorn sheep, for instance, engage in “homosexual courtship and copulation”; she lists their progression from nuzzling, to genital licking, to anal sex. This section was fun to read on its own merits, the book is peppered with delights of sentences like this: “No genital-genital contact has been reported among female vampire bats, but male vampire bats hang belly to belly licking one another, both with an erect penis.” But it also addressed some evolutionary implications of homosexuality. Under the Darwinian sexual-selection model, same-sex sexuality should not be evolutionarily successful because it does not in itself lead to more reproduction. The fact that we see it today must be explained away as an anomalous genetic mutation or social invention.

The bighorn sheep, a symbol of rugged outdoorsiness, has predominantly same-sex sex for most of the year (via animals.nationalgeographic.com)

But under Roughgarden’s social-selection model, same-sex sexuality has a range of other functions, all of which do become evolutionarily advantageous within a cooperative species: to secure a position within a social group or to ease camaraderie and teamwork between species members. Male bottlenose dolphins, for instance, often pair-bond as adolescents, and maintain a constant and life-long relationships as monogamous sexual partners and companions. And female red squirrels occasionally form life-long bonds, jointly raising a litter of young and having sex. In both of these cases, the teamwork between two individuals within a species leads to a longer life span and better reproductive outlook for offspring, no matter whose offspring it is. Roughgarden spends a significant amount of time discussing sexual behavior in bonobos, for whom strategic sex with any partner can facilitate sharing of food and resources, reconciliation, bond and coalition forming, all of which are important in a species that relies heavily on community.

When bonobos are presented with a large quantity of food, bonobos will routinely engage in about ten minutes of sex before eating – facilitating good relationships and sharing (via cnn.com)

I’m still hung up on Part 1 of Evolution’s Rainbow — I’ve been reading aloud and quoting it to friends all week with seemingly inexhaustible sentences beginning with, “Well, did you know…” But the second and third parts promise to be just as interesting, in different ways. The middle third of Roughgarden’s book is dedicated to exploring, in similar ways, the biology of human sex, sexuality, and gender development. She discusses the difference between diversity and disease, and the disservice that the medical and other communities have done to genetic diversity by harming or stigmatizing anyone who doesn’t conform to an undefined and amorphous sense of “normal”. And in Part 3, she expands her biologist’s lens to include social sciences of gender and sexuality variations across cultures and history. She particularly spends time looking at diversity and equality from a Biblical standpoint, because she recognizes that there are some people for whom the Bible and church teachings are the ultimate arbiters of what constitutes morally right and wrong —no matter what scientific conclusions we come to.

I have been basically glued to the pages of this book since I received it, even to the detriment of writing this article about it. But in articulating all this to you, I think what feels so valuable about it to me is the way it discusses gender and sexuality variance from a standpoint of biological variance – a different angle than we usually get to see. Though I work in a totally different field of the natural sciences, I know that my worldview is to a large extent shaped around this identity of “scientist,” and my academic training has led me to particularly appreciate argument based on scientific reasoning. Much of the argument I see in the world about queer issues is on a more philosophical or religious basis, or – my favorite – opinion couched in pseudoscience. It is this pseudoscience that she most effectively takes down in this book, by providing a well-researched, well backed-up scientific rejoinder. What I’m saying is that she speaks my language, and I love it.

It’s a book big enough and detailed enough that there’s no way to mention every insight — but for those of you who have read Evolution’s Rainbow, what else did you feel particularly drawn to? What were your favorite parts? What have I left out that shouldn’t be missed?

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

Queered Science: Historic Women Pioneers

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

The New York Times recently profiled a new exhibit showcasing 32 pioneering women scientists – including Florence Nightingale and Sofia Kovalevskaya, among others. It’s been three years in the making by three science historians — one woman, two men — and is now on exhibit until this weekend. Obviously I wish I could go see it — too bad I don’t live anywhere near New York, nor can I fly there. But reading about it is almost as good. The New York Times writes, “The exhibition celebrates their accomplishments, and makes it plain that they are all the more extraordinary given the deeply entrenched biases they had to overcome.”

I remember reading The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir in my early days as a feminist —at a time when I was trying to explain, to myself, and to others — how it was that, if women were equal to men, why we didn’t see more of them acting in history. I had my own vague ideas about why — or notions, really, or feelings — but I couldn’t articulate them adequately. And then she explained it with quotes like this:

“One is not born a genius, one becomes a genius; and the feminine situation has up to the present rendered this becoming practically impossible.”

Simone de Beauvoir, what a bamf, posthumously still winning arguments about sexism (via philosophy.uoregon.edu)

And then I was like, yes, those were the words I was looking for! It has nothing to do with the innate characteristics of women (because that idea is a fallacy if ever there was one) but rather the way people who are identified as “feminine” by society are treated, or not treated: the stories they are told about themselves.

All that philosophizing aside, de Beauvoir explains in detail the ways — at least up to her time, in the mid-1900s — that women of equal intelligence were kept away and turned down from institutions of higher learning.

And the women highlighted in this exhibit are some of the few who transcended, for whatever reason, those gender-related societal constraints on their intellect.

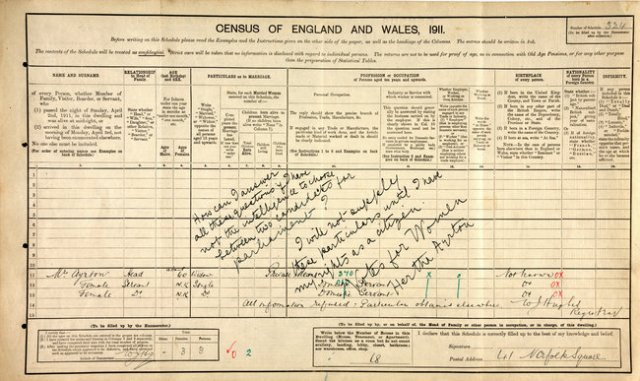

I personally love thinking about historic figures in science — envisioning what the cultural melee might have been around them at that time, envisioning how I would have acted in their situation. For instance, Hertha Ayrton, an electrical engineer and a suffragist, sent back her 1911 census form with these words scrawled across the paper: “How can I answer all these questions if I have not the intelligence to choose between two candidates for parliament? I will not supply these particulars until I have my rights as a citizen. Votes for Women.” Basically, I’m a badass, let me vote already. If you were in her shoes, what would you have done? Of course, she had already been denied membership in the Royal Society of London, and wasn’t even allowed to read her own work at one of their meetings. She changed her name as a teenager from Phoebe to Hertha, the name of a goddess. So maybe she’d grown a thick skin by then.

the 1911 Census form she refused to fill out (via: nytimes.com)

Or what about Mary Jacobi, born in 1842: she left a disappointing women’s college in New York for Paris, hoping to be allowed to study medicine. They apparently grudgingly allowed her to participate, but she had to enter the classroom by a separate door and sit alone near the professor. That must have been awkward, to say the least — I can imagine the feeling of all your classmates’ eyes staring at you behind your back, wondering what you’re doing here, feeling always unwelcome, but sticking it out anyway. What kind of emotional fortitude must she have had, in addition to her intellect?

Dr. Jacobi eventually went on to win a prize from Harvard in 1876 where she proved scientifically that, in contrast to popular belief, women’s intelligence was not impaired when they’re on their period. Next time someone tells you your legitimate anger is “just PMS,” (hopefully never?) thank Dr. Jacobi in part that you can prove them wrong.

Mary Jacobi: she does not look very happy. Probably because she’s been made unwelcome in every medical establishment she’s tried to join (via green-wood.com)

It’s often almost impossible to definitively identify queer figures in history, especially queer women. Sexual or romantic attachments between women were often easily overlooked by those writing history. “Romantic friendships” were common between women, and could mean many different things. And you could argue that definitions of sexual orientation are a modern and socially constructed concept – so maybe the point is null and void anyway.

But, nevertheless, you might like to know about two of the scientists featured in the exhibition, Florence Nightingale and Sofia Kovalevskaya, who are also featured on NOGLSTP’s list of queer scientists of historical note. Nightingale never married, and strongly rejected offers of marriage more than once. She often referred to herself in the masculine, as “a man of business” or “a man of action,” but kept up intimate emotional relationships with women her entire life.

Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler and Sofia Kovalevskaya. Anne-Charlotte herself was an important feminist author in Sweden.

Kovalevskaya’s marriage was well known to be a marriage of convenience; she needed written permission from either her father or a husband to study abroad, so she wrote up a “fictitious marriage” contract with a young paleontology student, and they both moved to Germany. But after her husband committed suicide, she lived the rest of her life in a “romantic friendship” with the actress and playwright Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler.

The exhibit is up right now at the Grolier Club (47 East 60th St, New York) and if you have time in the next few days, go see it! And then please come back and tell me how it was!

Queered Science: Ms. Dr. Joseph Digs Derby and Dragonflies

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

Hi everyone, for this week’s profile we have one of your very own: Ms. Dr. Joseph L. Simonis, Autostraddler, roller derby player, and population ecologist at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. She just emerged from graduate school and got a job she enjoys in the field she studied, and has some good advice for other science-minded queers who are navigating the paths of grad school and research and careers and life goals and all of those angst-inducing choices.

The best part about environmental science work: summer field work. Joe at her graduate research field site, 2012 (via josephlsimonis.com)

Joe also writes extensively about being trans* in academia, and has a lot to say about being out at work as a scientist. She hates “coming out” as a process on its own, but says that:

“As a visible trans* and gender non-conforming person, I kind of end up being out without coming out at all…I mean, it’s pretty obvious when people see my name and then hear someone refer to me as ‘she’ or see me use a restroom or meet me in person that I’m queer. I try to really make that not be an issue at work, which I realize I can do because of a lot of other privileges that I have, but it’s a position that I’m hoping to use to make the general cultural dynamic be one where queerness isn’t an issue at work unless it should be…I mean, my queerness doesn’t directly affect my research or my ability to perform it, so to me, it shouldn’t be an issue.”

A self-proclaimed “total nerd” in high school, Joe has always loved math and science, and also spent time hiking and camping with her parents as a kid, so the stage was set early for an interest in ecology. She graduated undergrad from the University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign with a degree in Integrative Biology.

But things were really cemented for her when Joe did an REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) internship in Michigan. Now, if you’re interested in science, and you’re an undergrad, you should definitely know about these. Basically, the National Science Foundation funds undergrads every summer to work with researchers at major universities on their research projects. And this is no making-coffee-and-copies kind of internship. The REU program makes a point of really involving their interns in the research process, so by the end of the summer you really accomplished something for whatever research project you were with, and interns often come out with a really solid idea of what they want to study and how to continue that work in grad school or as a career. For instance, Joe ended up publishing two papers from her work that one summer – a big leg up in the research world.

I also was an REU intern for a summer a few years ago, and I spent the summer thinking about what sea ice conditions in the Arctic probably looked like about a hundred years ago. And – like I said – that experience really formed for me a sense of what I wanted to study (and actually, even the fact that I wanted to continue in research at all). If you’re interested, look them up; I think deadlines are in a few months, more or less, so you still have time to apply!

Anyway, Joe did an REU in Michigan for a summer, with a project “looking at host-parasite interactions in a freshwater crustacean.”

“It was a pretty awesome project in general, but I also happened to be working with a post-doc who was very quantitative-minded and was developing mathematical models to describe the system and its behavior, but he was using data to construct and evaluate those models…it just really clicked for me then, that doing mathematical biology was something I was really interested in, and probably well suited for, given my personal history and education. But I didn’t want to just do the mathy side of things (be a strict theoretical ecologist), because I like the biology side as well, and I realized through this experience that it was possible to ‘sit in the middle’ and work with data and models.”

Joe is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Lincoln Park Zoo, where she works on using the data they have on threatened/endangered species to “manage them so they have as viable populations as possible in the long term.” For example, she’s developing a population viability analysis (PVA) model for an endangered species of dragonfly native to the Chicago area.

The endangered Hines Emerald Dragonfly (via onearth.org)

“In reality, this means I stare at my computer most of the day, but I also get to look out of my office window at hyenas!” But she definitely didn’t always expect to be here. Coming to the Zoo was a really conscious choice to get out of academia; when she went to grad school, at Cornell, Joe assumed she wanted to be a professor and academic as a career. I mean, why wouldn’t you? She was good at science, loved the process of getting to “ask and answer” research questions that really interested her, and she’d found a niche that really worked with her interests. But by the end of her Ph.D., she realized she needed a job that had some more strict external limitations.

“I was working ~70 hours a week just to keep on top of the class, [a graduate-level biostatistics class she created and taught] but every time I sat down to write lecture notes my brain would be on a grant proposal. My work suffered and I was miserable. Even during the few hours a day I was not working, my brain was thinking about work. At a time when I could have really used some personal space, my personal life suffered and I was miserable for it. Suffice it to say that my personality type and work habits don’t work well in an academic environment, and I figured that out first hand.”

The Lincoln Park Zoo hyenas: what a cool office-window view (via dynamicecology.wordpress.com)

Happily, her decision to get out of academia was completely supported by her advisors and academic mentors; while sometimes deciding to leave the academic world can be seen as something of a cop-out, none of her peers or mentors took it that way, and neither did she. Obviously Joe could cut it in the academic world, but she had decided to opt for something different. And that was fine. “Now, I work 35 hours a week and get shamed for staying late. And I get to occupy all of my time with other things. Like derby and queers.”

She says the most important thing about her job search was just talking with people – anyone who was in a career something like what she wanted. “Introduce yourself to people at meetings, send random e-mails, ask your advisor if they know anyone doing what you’re interested in…whatever you need to do, find the people that are working in the field that you’re interested in, and talk to them!” After her position here, she could of course return to academia if she wants, but that’s a pretty far ways into the future. For now, she’s just happy where she is.

Joe: I’m so glad I’m playing derby instead of writing lecture notes…what a good decision. (photo credit: Gil Leora)

As for being queer in the sciences, Joe says she takes a relevance-based, limited approach to coming out: “I only bring up my trans*ness in situations where I feel like it’s directly relevant.” She points out that being trans* doesn’t in any way affect her views on “spatial food-web dynamics in rock pools,” or any of the other topics she works on, and so she sees no real reason to explicitly come out in the work place. She’s also happy to report that both in her old Ph.D. department and here at the Zoo, she’s felt supported by her mentors, advisors, and peers. Being open at out at work isn’t any harder than just being out in life in general.

Which is awesome. This is where we’d like to see all work places get, eventually: a place where being queer is neither an issue of extra importance or focus, nor something hidden and silent and nonexistent. Where people just are who they are and that’s that, now let’s go back to talking about spatial food-web dynamics already.

Disclaimer: The views expressed by Joe are hers alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of her employer.

Queered Science: Sexism Is For Everybody!

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

Hello all you science queers! I’ve found you an awesome talking point for your next social setting where you want to sound smart and informed (so…always?) A few weeks ago on Oct 3, The New York Times published a long article about women in science by Eileen Pollack.

Pollack has spent the last few years traveling across the country to different universities and talking to women and professors about the persistent dearth of women in science; she herself graduated with honors in physics from Yale, but didn’t pursue a graduate degree. “At the end of four years, I was exhausted by all the lonely hours I spent catching up to my classmates, hiding my insecurities, struggling to do my problem sets while the boys worked in teams to finish theirs.” Of course, she’s now a professor of creative writing at the University of Michigan, so her career path didn’t turn out that badly. But she always wondered in the back of her mind what would have happened, or how things would have turned out, if she’d continued on to a physics grad degree. Because even with all her success, she felt like a failure. “I locked my textbooks, lab reports and problem sets in my father’s army footlocker and turned my back on physics and math forever.”

Now, you may remember an article from this series a few weeks ago about Dr. Ben Barres, who was catalyzed to speak out about misogyny in the sciences after Lawrence Summers, then the president of Harvard University, said some really sexist things about innate differences in aptitude along gender lines. Well, Summer’s comments also made Pollack angry, and her indignation started her quest to learn more about the barriers that women come up against in the sciences. Funny, how the most abrasive and offensive instances of bigotry often springs a leak in the dam (a leak in the dyke, aahhh!) and starts groundswell of activism and lead to longer-lasting, change-making movements. So thanks, I guess, Dr. Summers.

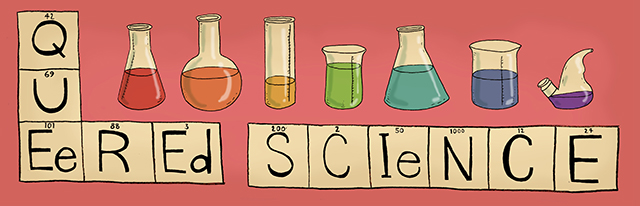

From Pollack’s article comes this picture: attendees of the Solvay Conference in 1927. Look for Marie Curie in the front row; she was the only woman in attendance.

via nytimes.com

In many ways Pollack’s article was important and timely. Discrimination in the sciences is an issue that direly needs more publicity and honest discussion, so I don’t want to discount her well-researched and articulate piece. But in many ways, from a queer-feminist perspective, it was a total disappointment. She missed a critical opportunity to widen the discourse when she said flatly, in her one and only mention of the queer population: “The lesbian scientists I talked to…reported differing reactions to the gender dynamic of the classroom and the lab, but voiced many of the same concerns as the straight women.” Other than this single mention of “lesbian” women alone, she does not include or provide room for any alternative gender or sexual identities.

Much of her language reveals a disappointingly essentialist view of gender that all of our lovely queer biologist and geneticist readers would quickly eschew. Also, she spends paragraphs talking about girls not doing science because of fears that boys won’t want to date them. She discusses shows like The Big Bang Theory, in which the scientist girl is depicted as geeky and undateable – and what girl would want to consign herself to that?

I don’t actually watch this show but as an aside, geek culture as shown by The Big Bang Theory has already been thoroughly debunked in feminist circles: that it welcomes male geekery with open arms, but can’t quite get around to allowing its girls the same thing.

via feminspire.com

Ugh. Obviously not all women want to date boys, and in a world of far greater concerns, is this really a question deserving of that much attention? What about the constant head-chatter of internalized homophobia and sexism as we walk through classes with no one who looks like us, day in and day out? Or the overt discriminatory remarks of classmates or, at times, professors? If you asked some of our earlier profiles, like Dr. Donna Riley or Rochelle Diamond, I doubt they’d say that wondering who would date them was even on the list of their worries. Diamond was fired after a co-worker sabotaged her work, and assumed for years it was simply reflective of her own lack of ability. Riley experienced written anti-gay micro-aggressions on the clothing of her classmates, and has repeatedly been insulted by other faculty solely on the basis of her bisexuality. Even you guys, in your comments on these articles, have some real and intense stories of sexuality-related discrimination and harassment. So in limiting her scope of attention to only heterosexual, cis-gendered women, Pollack unwittingly marginalizes a large segment of the very population whose marginalization she’s trying to highlight.

That large problem aside, many of her points are important and valid, and you should still know about them. For instance, she writes: “I was dismayed to find that the cultural and psychological factors that I experienced in the ’70s not only persist but also seem all the more pernicious in a society in which women are told that nothing is preventing them from succeeding in any field. If anything, the pressures to be conventionally feminine seem even more intense now than when I was young.” This is a problem that this series has highlighted: that there are still huge barriers to people of any minority status succeeding in the field — but they’re hidden, invisible, tucked away in professors’ and peers’ preconceptions and latent biases. We’re told there’s nothing holding us back, so if we don’t succeed it’s our own damn fault. And this, I believe, leads to the exact problem she described earlier: just as women are told there should be nothing standing in their way to success, the general silence around queer struggles leads the casual observer to believe that there is nothing standing in the way of their success.

Dr. Meg Urry, professor of physics and astronomy at Yale, spends much of her time working against sexism in science.

via news.yale.edu

And yet, there are huge obstacles. Dr. Meg Urry, a professor of physics and astronomy at Yale, wrote in an essay published in The Washington Post that women leave science academia in droves not because they are incapable, but because of the “slow drumbeat of being under appreciated, feeling uncomfortable and encountering roadblocks along the path to success.” But there is no single event that you can name and get righteously angry about. And, frankly, if you’re a smart woman or queer, and you know you can do better and be happier elsewhere in the work force, why would you stay?

Happily many of you have stories of being pleasantly surprised at feeling none of this; in our open threads I have been increasingly happy to hear those stories, that you feel nothing but acceptance and support from your advisors and peers, about your sexuality or gender or whatever. But some of you, also, have mentioned the exact kind of feelings of isolation or exclusion that Dr. Urry discusses. And this is the overriding strength of Pollack’s article: it discusses the persistent strength of latent biases, and that in and of itself is constructive and important. She is currently working on a book about women in science, and I hope that she will include more knowledge and understanding of all womens’ experiences, not just the cis-gendered heterosexual ones.

Author’s Note: After I published this piece, I contacted Ms. Pollack herself to ask about the dearth of attention paid to queer women scientists in her article. I appreciated her quick and polite response, and she explained to me that the article was only a small portion of a book with a much larger scope. Sections in which she did discuss issues of queer scientists were cut out by the Times at the last minute in the interest of brevity, and she herself was also “horrified” that the final product ended up being so heterocentric. We have discussed other queer scientists to potentially mention or reference in future writing on the topic, and all in all, it’s been a great communication! At the end of this article I write that I hope in her forthcoming book she includes a greater diversity of women’s experiences, and she has already done just that.

Queered Science: NOGLSTP’s Rochelle Diamond Forged A Path For All of Us

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

Rochelle Diamond works at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology) as the applications specialist and lab manager of the Flow Cytometry/Cell Sorting Facility. She is also the chair of the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals, (NOGLSTP) which we’ve mentioned before as an important step young queer scientists can take to get connected to others.

Rochelle Diamond (via sciencemag.org)

We talked on the phone the other day and I asked if I could ask her some personal questions along with the professional ones – she laughed and said absolutely, she’s an open book. Which is a good thing, because if any of you have ever experienced homophobia in the workplace or queer-related adversity in your personal life and moved on (ahem, way too many of us) then you need to know her life story. She grew up and forged a career for herself in the sciences – first as a closeted lesbian, then as an out activist, in a time when LGBT rights were in their nascent stages.

She likes to joke that she had a real coming-out — as a 16-year-old debutante in Phoenix, Arizona, where she grew up.

(via its.caltech.edu)

She was always the black sheep of the family; the youngest child, she couldn’t be swayed from her tomboy ways. Her parents tried putting her in charm school, but she proceeded to fail out: “I didn’t want anything to do with it – they gave my father his money back.” Instead, she was much more interested in science. “My brother would bring home his microscope and we’d go jump the fence to grab some pond water and look at it together.”

In her senior year of college, she got married to her best friend, a man just returning from Vietnam. He had Krohn’s disease and needed health insurance; she had health insurance and good connections in the medical field. Besides, her mother was soon to die, and she wanted to reassure her. “I wanted her to know I’d be ok. Of course,” she laughs, “she still wasn’t pleased because he was Jewish.” But at least this unruly tomboy daughter was respectably married.

Diamond’s husband was aware that she loved women, and for the most part, he didn’t mind. They were married for 10 years until Diamond fell in love with her first serious girlfriend; they realized their marriage wasn’t working and they divorced. And they remain friends today, “He calls for medical advice sometimes, and if he ever needed anything, of course I’d be there,” Diamond says. In 1974 she graduated from UC Santa Barbara with a dual bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology.

Diamond says she basically always knew she wasn’t straight, but she waited until both her parents were deceased and she was well-established in adult life to come out to her family; she was fairly sure that revelation wouldn’t go well. And it didn’t, really. “I was 26 or something, when I finally decided to tell my brother. I told him in the car while we were on the freeway — I thought he was going to crash.” Over time, the younger brother and his family grew to accept, if not approve of, her sexuality. Her older brother never has, though. When her younger brother told him, his first instinct was to institutionalize Diamond. “My [younger] brother called me up and said, ‘Make sure you don’t put your address in the phone book’,” just in case her older brother decided to go looking for her.

Diamond got interested in activism from experiences of homophobia of her own. While she was out to some family and close friends, she was definitely not out professionally. But while working at the City of Hope Research Institute a few years later — in the same lab with her husband — a co-worker found out that she was having an affair with another woman in the department, and began to sabotage her work slowly but surely. She was let go soon after because she wasn’t making any progress. The worst part of that is that she didn’t know at that point why her work was going so badly — it just was, so she accepted the decision and assumed the failure had to do with her personally.

“Then my ex-husband called one day, though, and he’d had lunch with some people, and Jim [the co-worker] had a few too many margaritas and told everyone how he’d basically run me out of the department.” That was the first she knew of intrigue. “I thought, oh, you know, I wasn’t an engineer, maybe that explained it…so when I learned I got really, really angry.” And so while she began a new job working at UCLA, she also started going to lesbian and gay scientist meetings in Los Angeles. “I never want to think that anyone else will get fired for their sexual orientation like I was,” Diamond says.

This happened in 1981, and there was no legal recourse for such a situation. Now, you might be thinking it’s a good thing we’re in 2013 now and things like that can’t happen anymore! But you would actually be wrong. The Employment Nondiscrimination Act still has no mention of sexual orientation or gender identity, even though such a clause gets brought up every year, so there is still no national-level protection against LGBT-related discrimination.

After a year of “craziness” at UCLA, Diamond submitted her resume to a new position as a lab manager for a new, very young woman researcher, Dr. Ellen Rothenberg. They talked for five hours in her interview, and Diamond came out explicitly then and there: “I am a lesbian and an activist, and if this is gonna be a problem, we should stop right now.” She was unwilling to go through another situation like she had at City of Hope. But Rothenberg shrugged and said that was not a problem; her last lab manager was gay and he was great, so she didn’t see why it should matter.

Dr. Rothenberg (via caltech.edu)

And from the way Diamond tells it, her work life has been nothing but unicorns and rainbows ever since. They just got a paper published in Science, and another in Blood. “We’re finally starting to solve some problems.”

Diamond has also been happily married for over 30 years to another chemist, Barbara Belmont, the President of American Research and Testing, Inc.

Barbara Belmont (via sciencemag.org)

Belmont was just made a fellow of American Chemical Society for her work on diversity in chemistry. They met in the Los Angeles queer scientist activist world, first as friends involved with other people, but eventually fell in love. Funny how that happens, huh? And they are both in positions where they can be very out and very active without fear of negative repercussions. “I’m kind of more of a flaming lesbian than Barbara, I guess – but both of us, we’re just who we are,” says Diamond.

But they’re both very committed to filling the pipeline with other queer scientists. “We’re out here trying to get other people to come out and not be afraid and push visibility, because that’s what’s going to change the climate.”

They say, “It’s important to understand that if you do come out you will know where a good place to work is and is not. And if you feel uncomfortable after coming out then you shouldn’t be in that place. The point is to be yourself as much as possible. You want to feel safe in your own skin.”

And this is where NOGLSTP comes in. Its mission is to empower lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals in the STEM professions, and to educate their surrounding communities about LGBTQ issues. They also manage the popular Queer Scientists of Historical Note list, and run a popular mentoring program where young students or scientists can talk to an older role model. They give out two $5,000 scholarships every year and facilitate communication through the queer science community. They just collaborated with over 20 other STEM professional organizations to apply for a grant for developing a National Research Mentoring Network, that would include LGBTQ students in a larger and more intensive mentoring program. And they coordinate a gay scientist conference every other year called Out to Innovate; the next will be in 2014 in Atlanta, so if you’re interested you can start planning to go now!

Queered Science: Jeremy Yoder, Allison Mattheis and Surveying Queers in STEM

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

One of the main drives behind this series, as you might have already figured out, is to introduce smart science queers to all the other smart science queers who exist. Now, you might be thinking, shouldn’t there already be some statistics about us — some kind of survey or self-reporting count? The Internet exists, it couldn’t be that hard, right?

And if you were thinking that, you would be right, we could indeed self-report and count ourselves, and that has just been done by two smart science queers named Jeremy Yoder and Allison Mattheis. They just finished gathering data in a nationwide survey of sexual diversity in science, technology, engineering and math professions, called Queer in Stem. This is the first study of its kind, and the first research focused on scientists above the undergrad level.

The illustrated Yoder and Matthies, hard at work among wildflowers. (via Anna B. Hall)

Jeremy is an evolutionary ecologist doing his postdoc research on natural selection on the genetic code of a Mediterranean wildflower at the University of Minnesota. He did his Ph.D. at the University of Idaho. He’s gay, and out “in pretty much every context you can name. I grew up in a religious background, and I came out relatively late in life, only after I’d started my Ph.D.—starting grad school was when I actually started to meet and make friends who were gay. So my experience in science has really been that it was a place where I was free to be myself.”

Allison is an educational researcher, and just finished her M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota. She says, “I’m queer and anyone who spends any time with me will probably find out pretty quickly (people often read me as straight, however, because I’m a cisgender woman). I get that ‘what, you’re gay?!’ kind of reaction a lot which is annoying. As a middle-class white woman who works on issues of intersectional identities and social justice, I try to use that experience to remind myself not to make assumptions about other people, and also recognize the privilege(s) I have and use it to speak up.”

The two met and became friends when Allison hitched a ride to work with Jeremy’s carpool one day. Jeremy had been wondering about issues of LGBTQ equality and inclusion – he did some preliminary hunting on Google Scholar and couldn’t find any studies looking at people past the undergrad stage. (You might remember our article on Dr. Erin Cech and her study on LGB undergrad engineering students’ experiences — and her study was the first of its kind as well). Allison had done some work on queer issues previously, on “discrimination in school settings, transnational queer migration, and identity development.” So Jeremy asked Allison what she thought about the idea of a survey of a nation-wide sample of queer scientists – as a social scientist, did she think results like that would be publishable? “I responded, ‘are you asking me to teach you about doing research with human subjects? Sure!'”

They just published the preliminary results of the Queer Stem survey and answered some questions for me about what they have seen so far.

What have you learned from your results so far?

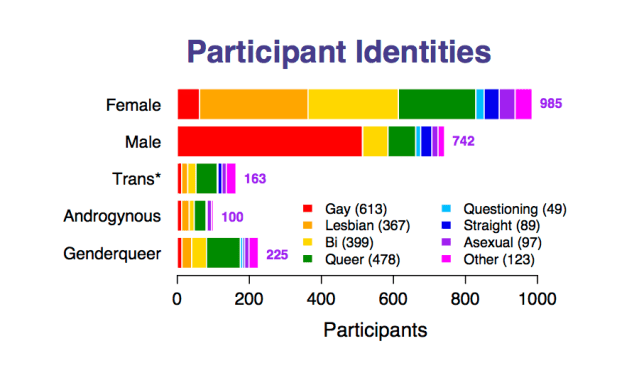

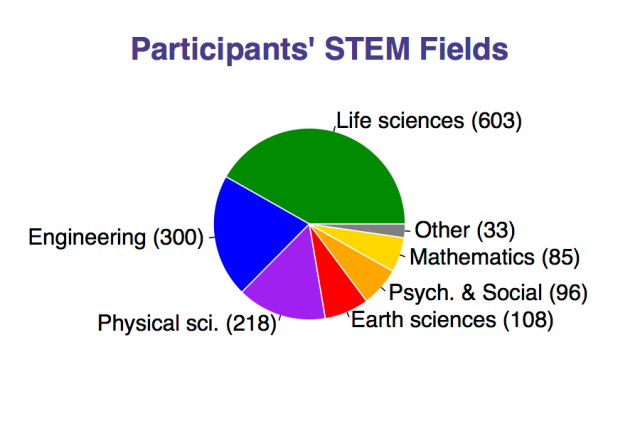

We’re only just starting to crunch the numbers, but what we’ve seen right off the bat is, there are actually quite a lot of queer people working in STEM fields. Over 1,400 people participated in the online survey, from every major region of the U.S., and even quite a few from overseas. We have representation from every major STEM field, and participants of all ages and career stages. And we have good representation of folks identifying outside the gender binary—11% of participants identified as trans* and almost 16% identified as genderqueer.

From their preliminary results, the self-reported identities of those who answered the survey. via queerstem.org

We’ve also begun preliminary analysis of the open responses and interview data (in addition to the survey over 140 people responded by email to ten open-ended questions and we interviewed 60 people individually). The quantitative and qualitative data both suggest that there are some very specific things that can make a big difference to people’s experiences, for good or bad — like whether there’s formal institutional support for LGBTQ people, or whether people are able to identify mentors or role models with similar experiences.

Again from their preliminary results, the STEM fields we work in. We’re everywhere, you guys! (via queerstem.org)

What are the most interesting leads/threads you’ve noticed either in the analysis of your data or in carrying out the study itself?

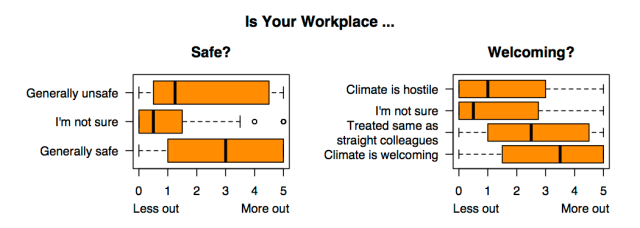

Jeremy: Across STEM disciplines, we saw people are mostly very out in their personal lives, but less out to colleagues or students. Interestingly, the factors that seem to predict how out people are in professional contexts aren’t the size of the school where they work, or whether they work at a private or public institution, or even the part of the country or the size of the town where they live; what makes a difference is whether they rate their workplace as safe and welcoming, and whether their employer provides benefits and support for queer folks.

Interestingly, the question is: do people come out because they feel safer to do so, or does the work environment feel safer because they, and others, have come out? (via queerstem.org)

Allison: I’ve begun identifying particular issues that seem relevant to most of the participants and those that are more specific to particular people’s experiences. For example, whether or not respondents report having regular interaction with a supportive queer community outside of their professional work is an external factor that impacts both personal and work life. Individual characteristics like gender identity, a racial or ethnic minority, age, and religion are significant for some participants and less so for others.

How have your peers/advisors/etc. in academia responded to this study?

Jeremy: My boss has been very supportive, and interested in what we’re seeing. That’s been my experience in talking to straight colleagues across the board, really. And, in fact, I’ve been asked to present results from the survey as part of a seminar and discussion series on diversity in biology that’s been organized by the College of Biological Sciences at my university.

Allison: The response has been great and people are very interested in learning more about our findings, both in my field and beyond— I’m that person that tends to meet you at a party and then talk your ear off about research.

Caption: Yoder and Mattheis – last-minute survey recruiting at the Twin Cities Pride Festival earlier this year (via Jeremy Yoder)

Where do you hope to go from here?

Jeremy: We’re hoping that we, or someone, will be able to do a follow-up version of the online survey in the next couple years. That would let us start to estimate how many queer-identified folks are actually out there working in STEM, and how representative our sample is. There are also all sorts of new questions we’d like to ask, or questions we’d like to ask in a different way, now that we’re starting to look at the survey results in depth.

Allison: We have had many people (both respondents and other researchers) write and tell us how excited they are that we’re doing this study and that has been really great. In my new position as faculty, I’m also looking forward to being able to mentor graduate students with interests in these issues, and to hopefully involve students in our ongoing analysis and writing. [Allison just accepted a position at California State University, Los Angeles in the division of Applied and Advanced Studies in Education, so if you’re anywhere near there, watch for new work from her!]

What do you hope for in the future of academia and social justice?

Accessible to people of all identities, ethnicities, and economic backgrounds. Science works best when it’s informed by a wide diversity of perspectives. We also hope that queer research and advocacy efforts will be enhanced by greater recognition of how many LGBTQ individuals are out there doing innovative and valuable work in STEM fields!

Queered Science Interview: Dr. Donna Riley and Engineering Social Justice

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

Dr. Donna Riley is a founding faculty member and associate professor at the Picker Engineering Program at Smith College, the first engineering program at a US women’s college. In 2005, she received an award from the National Science Foundation for her work on implementing and assessing critical and feminist pedagogies in engineering classrooms. She holds a B.S.E. in Chemical Engineering from Princeton University and a Ph.D. in Engineering and Public Policy from Carnegie Mellon University. In 2008 she published Engineering and Social Justice (Morgan and Claypool, 2008), and in 2010 was awarded the NOGLSTP Educator of the Year award for her work on combining social justice work and science pedagogy. She is out both personally and professionally as bisexual, and speaks as articulately about biphobia to the queer community as she does about homophobia to the heteronormative world.

Her work on feminist and critical pedagogy is what originally piqued my interest; we’ve talked before in this column about the tendency of STEM fields to exclude discussion of social justice issues, but Dr. Riley mixes together Paulo Freire, thermodynamics and bell hooks into one happy stew of learning of all kinds.

This year she is not teaching at Smith; instead, she’s actually in Washington serving a one-year stint as Program Officer at the National Science Foundation in the division of Engineering Education and Centers. Even so, she was excited to participate in this series and answered a number of questions for me. They’re so complete, as is, that I’ve left most of them intact for your reading and devouring pleasure. Enjoy!

The Envisioned Donna Riley by the Fantastic Anna Hall

You got an undergraduate degree in chemical engineering, and a graduate degree in engineering and public policy. How did it feel to be a woman and a member of the queer community in those settings?

I could write a separate volume about my experiences of sexism at Princeton and CMU, and they are many and horrific. So I will just leave that alone and focus here on anti-queer stuff….

In the early ’90s at Princeton, there were only a handful of students who were out as LGB people, and there was one staff member we knew who was just coming out on campus as transgender. Lots of us were scientists and engineers, actually, though I didn’t put my professional identity together with my sexual orientation very consciously. I mostly just wanted to find other queer people. Within the sciences and engineering among our peers and faculty, we were mostly just met with silence. We knew to compartmentalize, and we knew when and where it was safe to be out – and that was definitely not in the engineering building.

Were there any instances in which you felt discrimination, overt or otherwise?

The most overt anti-gay acts in the engineering classroom that I experienced happened on Gay Jeans Day. Our campus had one of these days where to raise awareness about what it is like to be LGB (we hadn’t added the T yet), we asked people who supported LGB people to wear jeans. We advertised this in every mailbox, every signpost, everywhere so no one was clueless about what day it was. And people who normally wore jeans would wear suits, or khakis, a nice dress, anything to show they weren’t gay and didn’t approve. Some of the fundamentalist Christians would make t-shirts that said “love the sinner hate the sin” and wear those with either jeans or slacks, depending on how they interpreted things. I remember sitting in my ChemE classroom waiting for the professor to walk in, most of my classmates in khakis, some with micro-aggressions scribbled on their shirts, adrenaline shooting through my veins, as each year there was typically a conversation where the men would express something homophobic like “No way! Wouldn’t be caught dead wearing jeans,” or whatever. And our professor would stroll in, not wearing jeans either, possibly actually oblivious, or possibly comfortably homophobic. There was utter silence from them on any and all social issues. In science and engineering culture this is called “being objective.” But this was a day that you couldn’t be neutral, and every one of the faculty picked the anti-gay side.

Outside of the classroom I experienced two major incidents of homophobic harassment. The first was at a party my first year, where a guy pressed me up against a wall and ordered me to “suck his dick to prove to him I wasn’t a dyke.” His language. I got away from him and got myself home. It didn’t help that I was not yet entirely out to myself at that point. My senior year, the night Bill Clinton was elected, I was walking with two gay friends back to our dorms, jubilant, when a group of ROTC guys came up and yelled “NO MORE GAY RIGHTS” at us. It was a little weird, kind of a non sequitur, though it was clear they were drunk and pissed that Clinton had been elected. As we were looking at each other apprehensively, trying to figure out what we would do if they attacked us, they thankfully moved on, and we let out a collective sigh of relief and went home. We wrote a letter in the school newspaper documenting and protesting the way we were treated.

Within the LGBT community I have experienced biphobia in every campus community I have been a part of. In undergrad I was publicly called a “player to be named later” by a lesbian and in grad school publicly called a “poseur” by a gay man. Later at Smith a lesbian professor referred pejoratively to a colleague in Mathematics as a “bisexual atheist” when the conversation was about the professor’s objections to having a Dean of Religious Life at Smith. I still don’t know what her bisexuality had to do with anything, except to communicate its unacceptability.

Many scientists describe the difficulty of deciding to come out, knowing the heteronormative culture of the scientific community. What helped you make the decision to come out, and what kind of responses did you get from colleagues?

In college and grad school I was very out on campus as an activist, so my peers knew because it was widely public, but it rarely came up in classes for any kind of reaction from them. In grad school my dissertation advisers and other faculty with whom I had a closer relationship knew my partner was a woman and I am fairly certain we attended departmental events together. My advisers each recognized my partner in the same way they would recognize a student’s significant opposite sex relationship and that really helped me feel welcome.

I came out in my academic writing explicitly in 2003 because I knew that situating myself relative to relations of power in engineering, in academia, and in society as a whole was essential to the project of introducing critical pedagogies in my engineering classes. I was already out to a lot of students. Others assumed I was queer because of my use of gender neutral pronouns, and some picked up on a rainbow ribbon I posted in my office.

I choose again and again to come out and be out. For me it is a matter of both personal integrity and political commitment. I have to be who I am, and I have to work so others can be who they are. This is risky, and it comes at a cost, but I believe the costs of being closeted are much greater, both personally and politically.

You describe your work as liberative pedagogy. What does this mean in practical terms, in the classroom and in interactions with students?

I actually treat this as an open question in my classrooms – I present some ideas from the family of critical or liberative pedagogies – feminist, anti-racist, queer, post-colonial/decolonizing, and others – and ask what it would mean for students to find a classroom liberating – from what? To what? Students are active participants in their own education; I am trying to do away with what Freire called the “banking system” of education, still so common in the sciences and engineering, where professors are assumed to hold the knowledge, make “deposits” in students’ minds, then ask them to regurgitate knowledge on tests. I am instead trying to have students bring what they already know from the authority of their experience, share knowledge among the class, and translate theory into action for change in some way. Together we question the silences in our field around race, class, gender, ability, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and other forms of identity, and ask what we are learning about diversity when it cannot be discussed in professional science and engineering settings.

“Whoever teaches learns in the act of teaching, and whoever learns teaches in the act of learning. –Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of Freedom.”

via ideiacriativa.org

You’re a founding faculty member at the engineering school at Smith, the first women’s college to have an engineering degree. What was that process like?

It has been a huge thrill and the fulfillment of a life’s dream to get to teach engineering at Smith. I wanted to leverage the liberal arts context in my own work, and it was probably the only place in the country I could have gotten away with testing out critical pedagogies in engineering classrooms, and integrating ideas from gender studies, sociology, and ethics in my engineering work.

At the same time, the persistent and pernicious trans-phobia of Smith as an institution has been a huge disappointment to me. Smith that simultaneously is not welcoming to trans* people really pours bleach on the rainbow of having an engineering program at a women’s college. We have had trans* and genderqueer students in engineering, but the rhetoric around being a women’s engineering program against the backdrop of Smith’s very public transphobia becomes very retrograde, and misses a tremendous opportunity to move the conversation forward.

Students protest when Smith didn’t consider the application of a transgender applicant earlier this year.

via usatoday.com

While overt sexism and homophobia are less common than historically, they still play out in ways that are subtle and, therefore, insidious and hard to combat. How do you see this happening in the sciences, and how do you deal with it?

One of the biggest sources of sexism and homophobia is lodged in the epistemology of science. How we think, and what we think, matter in determining what we know and don’t know, and affects our workplace interactions in very negative ways. We think that we eliminate bias by keeping our “personal lives” – some aspects of ourselves – out of the lab, classroom, or office. But actually this is how we allow implicit bias to seep in and saturate everything we do, because that which is male, straight, white, able-bodied, monied, is not left behind in the practice of science and engineering – it is just so normative that lots of us don’t notice.

I have learned that talking about these issues and building solidarity with like-minded others is the only way we can ever address them. Ultimately scientists and engineers have to be able to think outside the epistemological boxes we’ve been trained into to understand diversity and social justice. Cultural change takes a lot of hard work, it takes talking to people and organizing — skills typically not in our wheelhouses as scientists and engineers.

What do you envision for the future? If you could see your work come to fruition, what would that mean to you?

I dream of various incarnations of science shops or community-based research that are really rooted in community more than university; I dream of an engineering firm founded on a cooperative model that does projects in the public interest and in the interest of social justice; I want to develop more around the notion of feminist engineering ethics, to see what new models of social justice work in engineering might emerge. I want engineers and scientists to get directly involved en masse in the conversation about national priorities and be part of a shift away from militarism and policies that line corporate pockets to a more just, peaceful and sustainable future in the US and the world.

What would you say to young, queer-identified women just beginning a career in the sciences?

You’re not alone. See what community you find in NOGLSTP and oSTEM, and take part in MentorNet. Look for LGBT groups within your professional societies and join up early (engineering doesn’t have these yet – we need people to found them!). Be active in non-science LGBT groups too. Ask what you can do to contribute to the work.

And follow your passion. It is impossible to predict how careers turn out – you cannot plan a career trajectory in much detail at all, but if you do what you are passionate about you will develop the building blocks you need later to discover or put together the next thing – and you will create the sense that it has all led up to this…

Queered Science: Gender Bias OPEN THREAD

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

feature image from genengnews.com

After the last Queered Science post, about Dr. Ben Barres and how his transgender status gave him new insights into gender bias inherent in the sciences, we had a number of comments about gender bias, how to recognize it, and how to deal with it. Gender bias, especially in professional settings, is rarely an overt statement or action that you can name, report, write down, yell about or feel angry about. No, it’s much more subtle. Instead of leaving you righteously angry and ready to take down the whole department if need be in the face of your brave and downright meritorious cause, brushes with gender bias will often leave you with nothing but a rank pool of suspicion and self-doubt lurking in the pit of your stomach. Ew.

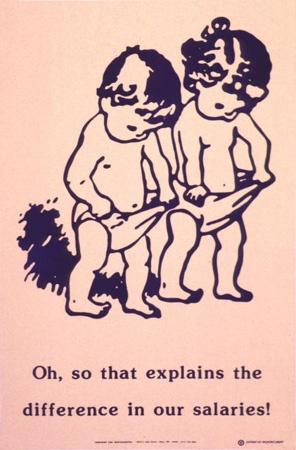

We are taught so young, y’all, so so young. (via thecollaboratory.wikidot.com)

So how do you handle this? How do you work for equality in your workplace (or school or neighborhood or life) while still surviving and trying to be seen as a successful human in your field of choice at the same time? This is what one gender bias expert, a law professor at UC Berkeley, suggests: smile a lot, make yourself less threatening, and soften your message so it’s easier for other people to accept.

Mary Ann Mason: “smile a lot. Smiling, just evolutionarily, means we’re friends. We’re not going to do you harm.” (via genderbiasbingo.com)

Or how about this one, from Joan Williams, law professor at UC Hastings.

Joan Williams: “you need softeners…to send femme-y signals, signals that you aren’t deficiently feminine…” (via genderbiasbingo.com)

This sounds like just trying to fit even further into the gender role stereotypes that are so constricting and problematic in the first place. Soften my message? Smile more – but definitely don’t flirt, that’s a line we have to walk, too? Ok so maybe people will like me as a person, because I’m being non-threatening and friendly, but those tactics don’t effect any real change. And, more than that, I’m leaving the exact same walls and barriers still standing in the way of everyone else who comes behind me.

Now, Williams does preface her statement with the fact that you really want to change the workplace expectations first and foremost. And I like her last phrase: “It’s better to be a bitch than a doormat.” But it’s frustrating that we even need to prove that we are ‘sufficiently feminine’ (and what does that even mean anyway?) to get further ahead. The idea that being stereotypically femme-y is a prerequisite to getting any good feminist work done is short-sighted, counter-effective, and just plain backwards. Like our awesome reader Becky said, this kind of advice is like handing us the psychological equivalent of an apron and frying pan.

But in thinking about other potential strategies, here is the problem I keep coming up with: fixing gender bias is not our responsibility. The burden should be on those who are biased, and if a coworker really thinks I’m less deserving /intelligent /reliable /creative /whateverthehellelse just because I’m a woman then there’s not a lot I can do anyway.

At the same time, if we don’t do it, who will, right? And if we want to succeed in a male-dominated profession, we are going to come up against this sooner or later.

So I’m asking you, dear readers — magical alchemists who take the cruddy drudgery of working in the world of misogyny and other assorted problems and turn it into nuggets of social-justice learning-moment gold — what do you do? What strategies do you or people you know (or could you, or could others) employ to combat gender bias or any other kind of latent discrimination? Let’s talk about it.

And here’s a little gold nugget of a video, just to end on a happy note.

Shauna Marshall, Academic Dean at UC Hastings: “It’s ok not to be liked. It’s better to be respected. So go with that.” (via genderbiasbingo.com)

OPEN THREAD: Coming Out In The Sciences, Let’s Discuss!

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

We’ve been talking recently about how it feels to be queer in the sciences, and in particular, a queer woman in the sciences.

And you guys had awesome comments of your own, so now we have a whole space to talk about just these things! We’re going to have a few different open threads, each on a different sub-issue of being queer in the sciences. I’m excited because I always have so much to say on this topic, but not a whole lot of people to say them to. From your comments, it looks like you all have things to say too! Like many of you mentioned, I often feel like I have to keep my science self and my queer self separate, but this is the perfect space to merge them.

First, one of the most basic questions: Are you out to your co-workers/ peers/ advisors/ bosses/ important people?

Yeah, smash’em! via jennamcwilliams.com

Like I’ve already mentioned, I wanted to come out for a while, but it never quite felt like the right time. I mean, when is the right time? We all know how uncomfortable it is when everyone else can effortlessly talk about their wives/kids, or at least have their presence assumed, and we have to sit quiet like the weird kid with no friends in the corner. But how do you casually interject a comment about your sexuality at the work party?

For me, it was a slow and gradual process, one co-worker at a time, either in the lab or in the field, and each conversation had my heart beating so hard it practically fractured my sternum, a huge rush of adrenaline and weak knees for an hour or so afterward. I didn’t come right out and say it, but a quick correction of their pronouns was usually enough to catalyze a discussion.

Then again, like I mentioned, I work in an accepting part of the world. Not everyone even feels safe about being out – the potential awkwardness involved isn’t even part of the equation. Many of the comments so far have mentioned feeling legitimately worried about losing jobs, opportunities for promotion, grants, or future projects.

This is for you, biologists. via inourwordsblog.com

So. Are you out professionally? If so, how did you do it? We all know that coming out isn’t a one-time ordeal, but kind of a constant coming out or being out – every new person you meet, you have to re-introduce your queerness into the discussion. What is your favorite coming-out story? How were the reactions?

If you’re not out, why not? What are your thoughts on the topic?

Queered Science: Why Social Justice and STEM Fields Should Hang Out More Often

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

The first profile on my list is Dr. Erin Cech, an assistant professor and researcher in sociology at Rice University. She is my new hero and could definitely be yours too, if —like me —your hero list involves academics and novel protagonists. Cech focuses on inequality in the sciences, and specifically the subtle ways in which women, Native Americans, and LGBT people are excluded through seemingly innocuous cultural processes. You should know her because she was the lead author on a ground-breaking study in 2011 on the experiences of LGB students in engineering departments. I interviewed her last week and frantically wrote down everything she said in order to share it with you; it’s very impressive. She just off-handedly spouted the quotes I have typed below, the kind of sentences that I take hours to formulate and perfect. Oh well, I guess that’s her job.

Dr. Cech, assistant professor in sociology at Rice University.

She has two bachelor’s degrees in electrical engineering and sociology, but had a lot of questions about the hegemonic culture that dominates science professions. She decided to go to graduate school in sociology in order to push the cultures of engineering and science towards more diversity and inclusivity from the outside.

“Sciences are perceived as an objective, neutral place. Who you are, and what you identify with, aren’t supposed to matter in whether people think you can do science — and yet it absolutely does. There is a consistent underrepresentation of minorities of every type, and it’s often difficult to understand why from the outset. I’m interested in how inequality is a really subtle process, and how we can reproduce inequalities without noticing that’s what’s going on.”

One of the most important parts of her research is what she calls the “self-expressive edge of sex segregation,” and you should know this, because she is talking about you and to you.

“The way we construct this idea of having a career or a major or a path and how it’s a way of expressing oneself, is such a dominant cultural narrative. It’s a very common frame through which people choose a major, that what you pick is somehow expressing who you are. And in this way it might mask subtle gendered processes: people’s interests come to be gendered, and that then becomes who they think they are. It feels legitimate and organic to them, and in many ways it is. But when people make decisions as a result of these expressive choices, the societal gendering of those choices comes into play. These choices are part personal choice, but a focus on choice alone hides, or cloaks, the very important presence of this lifelong gendering process under the guise of self-expression.”

In retrospect, I experienced this very thing in middle and high school. As a youngster, I was a super girly girl. My best friend and I dressed up as Anne of Green Gables and went wandering the countryside; my grandmother helped me sew water-nymph and fairy costumes that I wore to school on a regular basis in middle school. Yes, I know. And at some point, I think in eighth grade, I decided I was bad at math and didn’t like science. I wanted to be a writer, and writing and science didn’t overlap. QED, I couldn’t do science. For the rest of my public education, with that mentality, I put little to no effort into those classes and took my resulting mediocre grades as proof that I simply wasn’t cut out for it.

It was only in college, with a very different mindset, that I turned this totally around. Through a series of unrelated events, I realized I loved glaciers and wanted to study the physics of their behavior, and this – obviously – required math. So I started slowly but worked hard, remediated some of the bad habits and misinformation I’d learned in high school, and — guess what? Now I fucking love science, and I get paid to do it. It just took a slight tilt in my personal identity, and the realization that I could be creative, artistic, frilly and girly — and science smart.

Me working a lathe (a fancy metal cutter) to construct a thermometer-housing case in a mechanics shop at the University of Washington, post-transition into the sciences.

Dr. Cech explains this exact phenomenon, in sociology language:

“Interest itself, the way we learn what we should focus on, comes from experiences since birth that are often gendered. Subtle signs in teaching, parenting, media, or interactions with our peers all lead to cues about what women are supposed to like, and men are supposed to like. So even legitimate self-expression – interests, desires, etc. – can be informed by social processes.”

This leads nicely into a discussion of her 2011 study, “Navigating the Heteronormativity of Engineering: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Students,” co-authored by Tom Waidzunas (Temple University) and published in Engineering Studies. As a brief summary, she found that within the dominantly heteronormative culture of engineering, there are many prejudices against LGB students that may hurt their success in the field. No surprise there. But the interesting part is that, in contrast with other minority identities, like race, queer people often have a certain amount of control over their visibility.

“Queer students are often out to some friends but not others, so there’s this dynamic of information control, which brings with it concerns about compartmentalizing. They have their personal life versus school life, and they have to manage how to keep them separate. These boundaries, and the mental calculus involved, aren’t required in the same way with other dimensions of inequality.”

This is probably something that many of us have experienced, at one point or another, either personally or by proxy. Whether for a week or for 10 years, there is a span of time in the coming out process where we have to juggle who knows and who doesn’t know; how much to share at any given time; who is within the trusted, sacred circle and who is not. And we all know that this is not comfortable. But the difference here is that it’s the academic institution and all the latent anti-gay prejudices that ferment in its silence that creates the need for this juggling.

For instance, Jessie is a 20-year-old mechanical engineer who writes a blog called Musings of a Lesbian Engineer, to let off some of the steam of being closeted at school. (She let me use her real name, but on her blog she goes by Jane Doe.) I found her blog during my research and asked her for her personal insights, and much of what she said supported Cech’s conclusions. “As for who I am currently out to, I can count it on my hand…Namely my ex, and 5 of my closest friends from home. I base this on how much I trust a person, I also tend to avoid coming out if I worry about a backlash or negative reaction. I am not out to anyone in the engineering department at my school, my roommate may have guessed by now that I am gay, but I am not certain.”

If only it always happened like this.

Via fanpop.com

So students generally employ a combination of three strategies: passing (literally pretending to be straight and keeping their work and social lives completely distinct), covering (not necessarily pretending to be straight, but downplaying signifiers of gayness and gay culture around straight peers), and overachieving (making themselves indispensable to others, almost to make up for being gay). As you could probably predict, the results of Cech and Waidzunas’ study indicated that the constant navigating of these options adds a significant strain on these students’ energy and abilities, and often leads to a feeling of isolation within a hostile environment. Gay students might not even know about one another. Jessie agrees, “I’ve actually done the math and considering engineering is 85% men and 15% women, then there are 8.5 gay men and 1.5 lesbian women in 100 engineers. If they are anything like me I wouldn’t have a clue as to who was gay or straight.”

Interestingly, the coming out (or being out) experiences for these 8.5 gay men might differ significantly from those of the 1.5 lesbian women. Cech found that lesbians were often more likely to be accepted because the masculinity associated with the stereotypical projection of lesbians fits better with the image of typical engineers.