Queer Crip Love Fest: Love Is Showing Up

Over seven months of Queer Crip Love Fest, we’ve talked books, kids, pets, partners, breakups and more with some of the disabled internet’s most captivating queer folks. The goal of this series was to illustrate just how many forms love can take, no longer forcing us to wait for able-bodied saviors who’ve Just Learned So Much. We deserve space to speak out about our own passions on our own terms. I’m incredibly proud to have created that here, with all of our guests and all of you. And today, for the final installment, I could not be happier to introduce you to Nicole and Lindy, who have just the kind of story I want to end on.

Nicole had this to say about Lindy:

I love my girlfriend. She has perfect blonde hair and her laugh is the best thing in the world and she makes me feel like I’m full of glitter. We travel to see each other every month or so and count down every single day until we’re back together. We met on Tinder and she came to volunteer at the summer camp I worked at for a couple of weeks. She flew on a plane alone for the first time to come visit me.

I think it’s important to highlight that we’re both disabled in different ways; I have invisible disabilities, whereas she is legally blind and so we have two totally different kinds of access needs that we’re working toward mindfulness about. I think that disability has always been a part of our love; it’s a constant exchange, nothing is off the table, we’re always here holding each other and offering space for accessibility and everything else within our relationship. We acknowledge that love is growth and finding space to give each other what we need to make the world a more accessible place for both of us. It has changed my experience in love because I’ve never had someone love me the way that she does, and the way I love her.

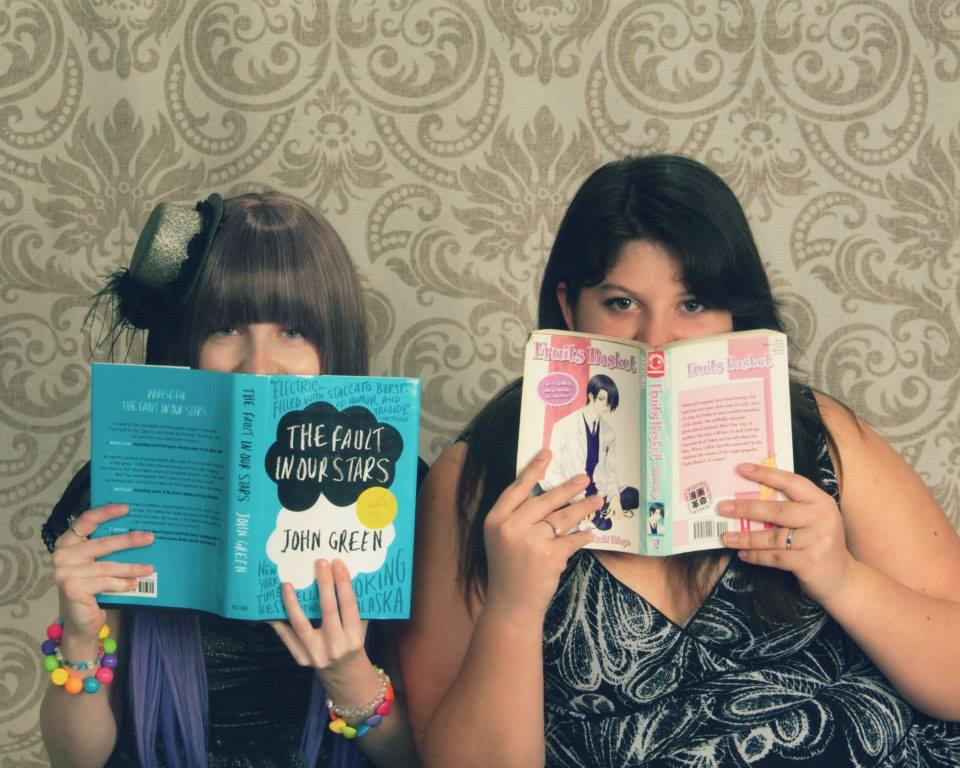

Lindy (left) and Nicole (right)

Who wants to see them at next A-Camp? Me too! But for now, enjoy our big gay sendoff with a bit of everything: lifeguarding, Lesbian Processing™, text etiquette and yes, True Life.

Why don’t we start with more about your origin story? I know that it’s adorable, but tell me from the beginning.

Nicole: So, Tinder. [Laughs]

Lindy: I messaged first. She didn’t respond for a while.

N: That’s because I was busy, first of all. [Both laugh] I was! It was the very beginning of the summer; we had just done the turnover from staff training to an actual session at the camp where I was working. I had just downloaded Tinder, and she said ‘Hey cutie’ with a smiley face, I remember that. And we got to chit chatting, and then moved over to Snapchat. I’d send pictures from being up too late in the office, just looking exhausted, wearing a fanny pack, clearly had not showered in days. Very camp manager. [Both laugh] Remember you were out at the bar, and you sent me something?

L: Yes, I was drunk.

N: Sent some great snaps. [Both laugh] Got real intimate, real quick.

So had you met in person at this point?

Both: No.

N: I was still in session, and you can’t really leave while that’s happening. Management doesn’t get breaks. So we hadn’t had the opportunity to meet in person, and then I kind of disappeared for a little bit.

L: For like, two weeks.

N: It was not two weeks! It was like, four days.

L: She’s lying, because I’m never that dramatic. I wouldn’t say it if it wasn’t true. [Laughs] So eventually I texted and said “If you don’t want to talk to me, I can take a hint” or something.

N: I was managing six program areas and about 150 kids, plus 50 staff. So it was legitimately a busy time!

L: And then you took your lifeguard class. Because you sent me a snap on your way there, and I was like “Oh, I’m a lifeguard instructor!”

N: And I was like “Well, that’s a really helpful thing to know, because we’re looking for one!” [Both laugh] So we still hadn’t met, but we did need another lifeguard. So I asked “Do you want to come to camp for a week?” and she was like…

L: “… yeah.”

Aww! So Lindy, you hadn’t even met her yet — how did you feel when she just asked you to come there for a week?

L: Well, I already had the week free; think I had something planned, but it fell through. So we met the day before camp started and went on our first date.

N: Yes. We went to Kerbey Lane — do you know what that is?

I don’t know what that is.

L: [Whispers] Oh, she’s missing out.

N: Yes, you’re missing out. It’s like IHOP but better in all the ways. You can get a swirl in your pancake, and they have vegetarian, vegan and gluten free options every day. And you can also get a carafe of mimosas for $12. I figured you should know that.

L: So we went on our first date there, and then I met all of her camp friends. I’m pretty good at going into random groups, and I thought I did pretty well. But they all had camp names and I was like “This is weird.” Then we went to the lake, and then we went to Dick’s Sporting Goods —

N: And then we went to Whole Foods and got some food in a box.

So you’re essentially just checking off gay thing after gay thing over the course of this one day.

L: You grabbed my hand at whole Foods.

N: I did. We held hands at Whole Foods. We do a lot of really gay shit. Get excited, this interview is about to get really gay.

“When one of us would walk into the dining hall or something, we’d text each other stuff like ‘Oh, your hair is so beautiful today!'”

So when you met in person, was the vibe definitely there? Because sometimes it can be tough with internet people, not necessarily knowing if you can make the transition.

Both: Yeah.

N: It was pretty immediate. And what was nice was that we’d had Tinder conversations, we’d had Snapchat conversations and we’d had a couple of phone conversations. So the vibe was there early on.

So you had to jump into this thing head first, because you were working together right off the bat. Do you think it was good to have total immersion with each other immediately?

L: I think it helped build a friendship instead of just a physical attraction. And also, seeing how each other interacted with other people, and how we are under stress.

N: In that environment, you’re gonna figure out pretty quickly who you do and don’t want to be around. So it worked really well on that level.

L: We’re not really allowed to be on our phones, so when one of us would walk into the dining hall or something we’d text each other like “Oh, your hair is so beautiful today!” Because we couldn’t really go up to each other and be cute either. But working together ended up being really good, because it taught us a lot about each other that we might not have learned until later.

And what about afterwards? Because then you have another big transition, so was it “Oh, I want to be with you,” or “Maybe this isn’t the right time,” or what?

N: We had made it official pretty quickly. We didn’t U-Haul it, but we did call it something pretty quickly. If we could have U-Hauled it we might have. [All laugh] But she did help me pack and go to the airport.

L: We bawled. I almost got my car towed because I got out and went inside with her. They don’t like that. [Laughs] But there wasn’t really a sit-down conversation. Because she wouldn’t have phone service in the middle of the woods in Vermont, which is where she was going, I wrote little letters to give to her, so each day she could open one. It would be like “When You’re Feeling Sad,” or whatever. And then she could open it.

Had either of you been in a long-distance relationship before?

N: I had.

L: Nope.

So what sort of agreements did you hammer out going into it?

N: That we are only with each other, and we’re going to make sure we keep up communication, agree to visits, switch off the visits. It was very clear from the beginning what our relationship was going to look like, and that if it needed to change, we could talk about it. It took practice. There were some moments of friction, some call out type things: “You’re not listening, you’re not paying as much attention as you could,” stuff like that. But what never changed is that we were happy to talk to each other.

L: I think part of it was we were scared because it was real. The stakes are so much higher. Plus you always wonder if it’s going to feel the same when you go so long without seeing each other. But we’ve been able to trust each other from the start.

“She asked curious questions in a respectful way, which people don’t do… She makes me feel like I have an open space to say when I need something.”

So you’re the first couple I’ve ever interviewed together, and also the first where both people have disabilities. I’ve actually never been in that situation, so I’m really interested to hear how it plays out in your relationship. The first thing I’m wondering about is disclosure, since that can be a huge issue when you’re meeting people online. Did you disclose your disabilities up front?

N: She told me that she was blind when I mentioned that I was applying for a job at a school for blind students. So we just kind of carried on, and I asked something like “So what does that mean for you? What does that do for your daily life? What do your access needs look like?” Not “Oh wow, so what’s it like?” in that morbid way.

L: She asked curious questions in a respectful way, which people don’t do.

Right! It would be amazing if more people did that for their partners — not “Tell me everything I feel entitled to,” but “Tell me what this is gonna mean for us,” which is a completely different question. Can you tell me more about that made you feel?

L: It was really reassuring. She seemed interested and not like she’s never been around someone with a disability before. She knew what to ask to make me feel open to want to share with her, and not have to justify myself or why I need printouts of PowerPoints, or to not use green marker on white boards or things like that. It was just really good. Sometimes I’ll feel attacked or like I need to defend myself when describing my disability to people; with her, that never happened.

On the other hand, when we would Snapchat, I could never read what she said because the font was so small, and I waited a while to bring that up. It was a couple of months until I was like “Hey, can I ask for a favor…?” And now we only use the bold, big fonts. When she forgets, she’ll just immediately resend the same thing with the font big. But she won’t take it to the extreme and overcompensate like people sometimes do. She makes me feel like I have an open space to say when I need something.

And what about for you, Nicole? Did you talk about your needs before or after that?

N: It’s never been a big, one-time disclosure, because I do have multiple things going on. There are some things going on with my body that are invisible disabilities, and then I have learning disabilities and mental health stuff. So it wasn’t that it came out slowly or that I wasn’t telling the truth, but there was a right time for things and a not right time. So it would come up like “Hey, this is a thing I usually have a handle on, but right now I don’t and I need support.” Dealing with both the physical and emotional exhaustion that comes from all this.

We made a lot of lists. She would sit on FaceTime with me —

L: And I would type the list for her. She would tell me about the things that she needed to get done within the week, so I’d send her daily reminders.

N: That was so helpful; it made things a lot more manageable. There was a window of time where I was feeling really depressed, and she helped me clarify what I needed to do, and whether I was taking my medication. That came up one time.

L: I didn’t mean it in a bad way, but one time I accidentally said —

N: We were arguing, and I was really upset. Instead of taking it as “Oh, Nicole’s upset and it’s okay to be upset” or whatever, it became “Are you taking your medication?”

L: For the record, I did feel awful about it!

N: But that is an important question! Are you feeling this way because you’re not taking care of yourself? That’s completely legitimate. It’s just a weird line to navigate, and a hard thing to ask, and a hard thing to be asked. Because you’re having these feelings, and you need the other person to know that they’re very real. So we navigated and worked on that.

It seems like you’ve negotiated the logistical access stuff really well, and that your needs and abilities complement each other. What about emotionally — how does it feel to be in a relationship with someone who understands access on a visceral level? Not “Oh, I should understand this concept because I’m a good person,” but “I understand this because I’ve been through it”?

L: It helps that Nicole had studied disability in school, so she knew how to ask properly. I’m pretty open; give me somebody who shows interest in disability stuff, and I will tell you what I need. So her giving me that made me feel like I could ask for those things without causing a problem. The knowledge to understand where I was coming from was really helpful.

Is there anything that’s challenged you about being in a relationship with another person who has access needs?

N: Not in relation to disability for me, really, beyond that moment of “Are you taking your meds?”

L: There have been more conversations around our ways of supporting each other. When I need support, it’s a mixture of “Please agree that this sucks” and a hug or a hand to hold. And then “Here are the things we can do to make you feel better.”

N: You also love a good platitude. [Laughs]

L: As you can tell from her tone [laughs], Nicole does not like platitudes at all. She likes “This fucking sucks, and I want you to understand that.”

N: I want her to listen and be there with me, rather than tell me about how it’s all going to be okay. Just for her to say “Yeah, that sucks, and I’m right here with you” — that’s all I want.

L: And I’m a fixer. So that was a huge issue that we had to figure out.

But that’s great — that sounds like a pretty standard relationship issue, and a really healthy thing, rather than this huge blowup around feeling like a burden, or whatever people might assume your problems would be.

N: That’s definitely true. We’ve gone through breaking up and getting back together, and it’s not because of any disability-related stuff at all; it’s been for the same reasons and followed the same path as it would even if that wasn’t a factor. It’s because things weren’t healthy, and then we worked on healing, and it was hard on both of us, and now we’re here. You just learn a lot about each other and come to that place of understanding.

We definitely had to negotiate how often to communicate and in what way, though, when we were first getting back together. Really be mindful of the line between what was and wasn’t healthy, and choose the medium carefully.

L: I sound like I’m in a mood whenever I text, because I put periods on things.

Why would you do that?!

L: People just assume I’m angry because I put periods on things! Which then does put me in a bad mood! [Laughs]

Rookie mistake. You can’t put periods on your texts.

L: That’s the real takeaway from this interview: don’t end your texts with a period.

“Love is in the things you choose to do and the way you choose to be and the people you choose to be with. I think it means that’s the person you give the last of your favorite candy in the bag to, the one you bring to a place you love and share it with them, the one you have total honesty and truth with even when you’re not quite so pretty in it. It’s being your gross self with someone.”

Okay, last big question: what does love mean to you? I want you to each answer this individually.

N: Do you want us to each leave the room so we can’t hear the other one answer?

If you want! I think that’d be cute.

N: You go first. [Leaves the room]

L: Bye! [Laughs] Okay, I’m ready. I think love means accepting each other with all flaws and positive attributes. Even when you’re in a bad mood, still loving them and letting them know that you’re still there and not going anywhere. Eliminating that fear of leaving is really big for me; knowing that they’re not going to leave when you have a bad day.

[Nicole comes back in]

We’re talking about you, go away! [All laugh, Nicole leaves]

That sense of security is big for me too, because it’s so rare to get from anybody. Knowing that you can show your whole self is such an important thing.

L: It’s like that in my family too; we can be mean to each other, but we know that we’re there for each other and aren’t going anywhere. I don’t mean purposefully, but getting into arguments and knowing it’ll still be okay. And I love having that security with Nicole. Because I’m not always great — no one is — and it means a lot to be able to let her know when I’m not having a good day, and have her say “Okay, thanks for telling me” and still love me is really important.

Great answer!

[From off camera] N: Can I come back now?

Yes!

[They switch places]

N: I think that love is in the things you choose to do and the way you choose to be and the people you choose to be with. I think it means that’s the person you give the last of your favorite candy in the bag to, the one you bring to a place you love and share it with them, the one you have total honesty and truth with even when you’re not quite so pretty in it. It’s being your gross self with someone. Lindy knows everything; she’s been around, y’know?

Love is taking the time, and just sitting there on Skype even when you’re not really doing anything. Love is sharing food, and asking for Sno-Cones and going to get them and then realizing you didn’t want them after all, but nobody gets mad because you spent time together. Love is showing up.

Wait. Can I tell you a secret?

Absolutely.

N: She was on True Life: I’m An Albino. And I bought the episode — didn’t just watch it on YouTube, I bought it. It was when she was in high school and going through her scene kid phase and it’s just so good. [Laughs] Love is being able to buy her awkward teenage moments on iTunes and watch them over and over.

Oh, this is amazing. I really wish I could put this in the interview, but I don’t want to out her MTV phase without her consent.

N: [To off camera] Babe? I have a question! [Laughs] You know how I bought the episode of True Life? Can that be part of this?

L: [Laughs] Yes, that’s fine. Thanks for asking.

N: See? Love is calling her over to ask if that’s okay.

This is the last installment in Queer Crip Love Fest. View the complete series.

Queer Crip Love Fest: Nana’s Stories and Ginger Loaf

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: disability is a family issue. But all too often, that means misguided portrayals of disabled kids as “burdens,” the assumption that no family would want a disabled child, and insistence that nondisabled family members always know best. What about all the other ways disability can play out in a family — as a source of empowerment, empathy and togetherness — particularly across generations?

To find out, I talked to Scout, a 22-year-old Māori queer person and aspiring politician living in New Zealand, who had this to say about love:

The first person that would pop into my mind is my great-Nana. She’s 93 (nearly 94), she has dementia and she lives in a secure dementia ward in a rest home that’s airy and bright and just like when she used to live with us. She’s been this one constant source of love and ginger loaf since I was tiny, and has watched me grow up. Because of the dementia, she’s the only person in my life who I will let call me by my dead name. Which is pretty big for me! Out of all her grandkids and great-grandkids, she remembers me the most often. I love the levels of unconditional love and optimism she spouts every single day. I love her fond stories about her childhood, and I love hearing them for the 14th time in a row, too. I really cherish every moment I have with Nana.

Read on for more about forging a political career while disabled, the importance of interdependence, and some excellent family lore.

Tell me more about yourself, and especially your political ambitions!

I identify as takatāpui; that’s a word in Te Reo Māori (the Māori language) that these days is used as an equivalent to the word “queer.” So it means a Māori queer person. I use the term to describe my gender and sexuality all at once — without it I’m “somewhere sort of like a boy but not a man but also really gay but not into guys.” I’m disabled and mentally ill. I believe in a world where we can be all these things and still live safely.

I’m really good at communicating with people simply and clearly. I want to use those skills for good, so I’m going into politics. I’ve already run in one election — last year, I ran for mayor and city council and I actually came within 180 votes of election, which was remarkable given my age and budget.

That’s incredible; as an American, I can’t even imagine a young, brand new candidate coming that close, so I’m really impressed. You have a lot to be proud of!

The neat thing is that in New Zealand, because our Parliament is made up of all these different people from different political parties, being elected is actually pretty achievable here. You don’t have to be a privileged millionaire. In the next ten years I see myself in Parliament, with a portfolio in something like social development. I specifically want to represent the trans community and the mentally ill community in New Zealand because we have no one in Parliament who can truly amplify what we have been saying for years.

“Part of the reason I’m trying to shift my community work from this activist, volunteer level up to being an actual politician is that I can affect change in a way that is better for my disabilities — I can work with my strengths so that I don’t exhaust myself doing everything else.”

Politics is a notoriously demanding field — lots of traveling, long hours, staying on top of multiple issues at once. How do you negotiate your disability, which can also ask a lot of you, in all that?

The political party I’m in wants to see a Parliament where we can have members who jobshare. Their focus is that it would be great for parents who deserve to have a voice but need to raise their kids too. I think it’s a fantastic idea, but I’m coming from the place where if I could share a portfolio and divide my Parliamentary responsibilities between me and another person with a disability, we could manage our lives so much more sustainably.

Several of my friends are members of parliament, or MPs, and I literally just sit here and watch them work from 5 AM to 11 PM — or later, some days, and they don’t get days off, and I see the impact of that on them behind the scenes. It isn’t a sustainable role for anybody and I think our attitudes towards work are so inherently capitalist and need rethinking. Taking a day off shouldn’t be the end of the world! Productivity doesn’t trump health!

Personally, too, I hold multiple volunteer positions where I have an incredibly high level of responsibility with zero compensation for that work, and it’s really difficult to do in a sustainable way. I can’t afford the doctor’s appointments, medications and supplements to keep myself well, even in a country with almost universal healthcare. Part of the reason I’m trying to shift my community work from this activist, volunteer level up to being an actual politician is that I can affect change in a way that is better for my disabilities — I can work with my strengths so that I don’t exhaust myself doing everything else. Maybe it’s a pipe dream, the idea that Parliament could be easier on my health, but at least being reasonably financially compensated for my work would enable me to access the healthcare I need to do the work.

Do you come from a political family?

My immediate family aren’t particularly political — my parents actually have polar opposite politics to me in many areas. My little brother is getting more and more interested, especially as this year he gets to vote for the first time, but neither of us was really raised in political spheres. I think I get the politics from my dad’s side of the family; his grandma, my great-grandma, used to speak about politics on a literal soapbox, and she and her husband were both staunch unionists — much like me! And I recently discovered that on dad’s dad’s side I’m related to the guy who’s been mayor of a city further south since 1993. He’s pretty well-liked! So it’s in my roots, at least.

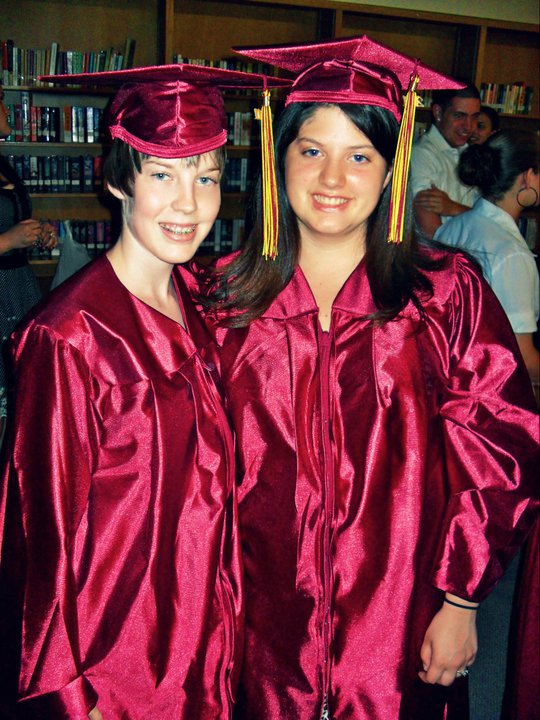

Scout and Nana, with strong fashion all around

Speaking of your roots, I want to hear more about your great-Nana and your relationship with her. Do you have a favorite story of hers?

My Nana Vera is a little 93-year-old English woman who grew up in London and watched Queen Elizabeth playing in the backyard at Buckingham Palace from her doorstep. She made excellent ginger loaf back in her day, and now I have the recipe too. She came to live with us when I was maybe 13, and she was always busy — she loves “cooking, knitting and sewing,” that’s her mantra — but she also would ask my mum to give her literally anything to iron and she would stand in the lounge at the ironing board ironing scraps of fabric or tee shirts or pants just because she enjoyed it.

One day my family went out to the lake on our boat. She stayed home, but she made us a bacon and egg pie to have for lunch and when we cut it open, she’d left the fork that she’d mixed it all up with inside. When I tell her that story now, she finds it absolutely hilarious. Nana has lots of stories — the clothes she and her siblings would make for the rats that lived in their London house, sleeping overnight in the tube during World War II when London was being bombed, the swimsuit she knitted herself, and when she dove into the water and stood up to find the woolen swimsuit stretched down to her ankles. We hear these stories over and over again now, often with details swapped out for those from another story, and I think we all cling onto the stories now because that’s going to be what we have left of her soon. The stories and the ginger loaf.

And you said you’re the great-grandchild she remembers most?

Yes — she doesn’t recognize me anymore because I’m an adult now, so when I see her and she asks who I am, I have to say “Hi Nana, I’m your granddaughter, [deadname].” Last time I saw her, she talked about being the one who gave me that name (even though my parents were actually the ones who did), and it was a bit of a twang to the heartstrings because she doesn’t know me as Scout. She knows me as this awkward 10-year-old with messy hair, and I desperately want her to know who I am now because when she does get snippets of me, she is so, so proud of me and how far I’ve come. She doesn’t know about my disability or chronic illness, but sometimes sitting with her gets really difficult because part of dementia is when people start to get confused, and they get paranoid and scared, and it’s much like psychosis. I’ve experienced psychosis quite a bit, I know how terrifying it is, and I’m such an empath that I really struggle to know that I can’t just take her hurt away.

Vintage Nana

That’s really interesting, because nondisabled people say that kind of stuff to me a lot — “wishing they could take the pain away” or whatever — and I’m wondering if that’s true for you. That sentiment can mean such different things, depending on the context.

Yeah, wanting to just magic the hurt away is a weird feeling to be coming from me! But at the same time, we’re talking about literal distress here — like emotional hurt. And I think for many of us as disabled folk, we’ve come to terms with what we experience — but Nana’s experience of dementia is sort of different in that she doesn’t always know what’s happening or who and what she can trust. We can be empowered about disability at the same time as acknowledging that some of it really, seriously fucking hurts and no one should ever have to experience it. Given that I’ve experienced psychotic episodes where I have no idea what is real, what is not, and what I can trust and hold with me, I would not wish that terrifying experience on anyone and it breaks my heart hearing Nana echo those same feelings. There is a lot that Nana cannot do anymore and a whole lot that she struggles with; at the same time, she’s an incredible baker, she knits pretty well, she always says the right thing even when she’s not very with it that day. She is overflowing with compassion for everyone and everything.

On her good days, she’ll tell me how much I’ve grown; on her bad days, she’ll tell me it’s “lovely to meet you!” I love how excited she is to see me, every five minutes.

“I’m glad she doesn’t know, in some weird way, because it means I have one person in my life who just assumes I’m competent unconditionally.”

You mentioned that she doesn’t know about your disability; was that a conscious choice, or has the timing just never been right? Do you wish she knew?

She hasn’t consistently remembered who I am for the last five-plus years, whereas I only became disabled in the last three years. So somehow it’s not really come up because she’ll just forget five minutes later. I’m glad she doesn’t know, in some weird way, because it means I have one person in my life who just assumes I’m competent unconditionally — and being disabled, y’know, not often do you get to just do things without people second-guessing whether you’re capable of them.

Absolutely, and I think that’s a great point to make here. It sounds like becoming disabled gives you a lot of empathy for her, but also a clear understanding of the different ways disability and illness can manifest and change your life.

Definitely. Since becoming disabled, I’ve had to rely on people for things a lot more. And I think a lot of the time the role of your best friends can be blurred into the roles of your carers. And with that, your carers and doctors and your whole team become part of your group of friends too. It’s fascinating to me how those relationships have helped me learn what is and isn’t genuine.

How so?

I have a lot of trouble trusting people enough to feel loved, but when I do, it’s because I can read someone’s genuineness in how they interact with me. Working in politics, y’know, all my interactions with people feel so fake some days. I love genuine conversation, I love when someone trusts me and when they just have that feeling about them that I can trust them too. I love when people don’t expect me to do what they’re capable of doing, when people are conscious of my limits but don’t decide those limits for me.

“I really despise this idea that dependence is ‘inherently bad.’ Humans are pack animals; I’m so sure that we have never been this doggedly independent in our whole history.”

I think the idea of “dependence” can get unfairly vilified, even in otherwise progressive spaces and among other disabled people. Dependence is not inherently a bad thing or a sign of failure, and can in fact be a source of empowerment, I think. Do you agree, or not, or have anything you want to say about that?

I really despise this idea that dependence is “inherently bad.” Humans are pack animals; I’m so sure that we have never been this doggedly independent in our whole history. People are so individualist in their approaches to everything now, even in progressive spaces. I prefer more communal spaces, I like the ideology of “it takes a village to raise a child,” and I apply that to how I exist now. There’s no point beating myself up for needing a friend to come sit with me on tough nights, or for always having to ask a friend to open difficult jars for me. That will just turn into some gross circle of self-loathing, and I’m not here for that.

I think we have to be careful with dependence — when it becomes a situation where the other person can’t do anything for themselves anymore, then that’s a bit of a problem. But it’s important to be able to depend on things like facts and the knowledge that someone can help us and the people we surround ourselves with. We need to support each other to make positive change together. That also means we have to take self-responsibility, look after ourselves, and remember that means asking for help when the job gets too hard.

So with all that in mind, what does love mean to you?

Love means that you can put your trust into someone and mutually agree that you will keep each other safe to the capacity that you’re able. Love is not conditional; genuine love is someone who sticks around even after I’ve been stuck in bed three days, or blown them off four times in a row because I can’t cope with leaving the house. Love is when someone understands that my behavior at a given point is out of the ordinary, maybe I’ve socially withdrawn myself, and asks if I’m okay without getting angry at me and taking it personally. Love is trust, safety and home.

Queer Crip Love Fest: In Control of My Own Narrative

Photos courtesy of Sandy Ho

Fun fact: when I’m not busy being professionally gay on the internet, I am a librarian. Right now that means taking a lot of inventory and reconciling our catalog (thanks, summer!), but obviously the top perk is getting paid to live among books all year long. I would be a disgrace to my profession if I didn’t devote an entire Queer Crip Love Fest installment to the love of reading. Fortunately Sandy Ho — an educator, activist, organizer and overall badass from Boston — has us covered.

“At first reading was something to pass the time in doctor’s offices. At one point I was really ashamed that this is how I first came to love reading: as a distraction from the ways my disability manifests in ‘health problems.’ But now I’m damn proud of the fact that that is how I first became enthralled. Through all the different ways my relationship with reading has fluctuated, it has also developed alongside my disability identity. As a child who experienced a lot of unpredictable physical pain, I gravitated towards books that gave me finite conclusions — the kind of resolution I wasn’t getting from my body. Once I got older, reading morphed into non-academic education and identity-seeking, a hobby that gave to me more than I took away. It’s equal parts salve and catalyst.”

Enjoy, fellow brainy weirdos!

One of the goals of this series is to celebrate the many forms that love can take, so I was excited when you specifically brought up reading and books. What does love of those things mean to you?

To me, love is freedom, and it’s also about respect. So freedom in the sense that I’ve been able to turn to reading no matter how confused I’ve been about my identity or my body — or even how proud I’ve been. That freedom to return to that place of comfort and empowerment is love. In my free time, I also work with a senior citizen who’s writing her memoir. Watching that process of putting a book together, I recognize that whether I like a book or not, it embodies somebody’s dreams and their end goals, and it took a lot of work. So even if I don’t love what they’re saying, I respect the time they took to produce something and share it with someone.

I’m interested in how reading evolved from something you did in the doctor’s office to something that empowers you. Can you tell me more about that?

I’m a child of immigrants, and I come from a family that’s always valued education. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the show Fresh Off the Boat, but there’s an episode where the mom takes her kid to the grocery store to cool off because she doesn’t want to turn on the AC — that was very much my mother, except we went to the library. My grandparents worked in the Boston Public Library growing up, so we were always surrounded by books.

At the Boston Public Library

Even though they never explicitly said so, I think it’s something my parents realized was empowering for me. My older brother leaned more toward math, and I was like “No, that’s disgusting.” So I would always just be reading stories. It was something to pass the time, but it was also something that just made everything go away for a while. There were a lot of things happening at the doctor’s office as a kid that I didn’t understand and were frightening, so having a book was a comfort for me. It was always those sorts of long-winded adventure books.

Was reading was a form of escapism for you?

Yeah, definitely — it was about escapism and distraction. And then when I started writing my own stories, I realized that I could be in control of my own narrative in a very basic way. I would make up characters who were basically aspects of myself, but I never brought disability into those stories — which is interesting, I realize now.

That was my next question, actually.

I’d never read a book with disability in it that wasn’t kind of instructional: “This is so-and-so, in a wheelchair, in a classroom,” and the wheelchair looks like it comes from the FDR era. Outside of that, I never came across disability in the stuff I read, or that I wrote myself. I think it was because of that focus on education, and this idea that “Look, if you just do well in school, you’ll be able to do X, Y, and Z, and let’s just treat your disability when it comes about, as necessary.”

I relate to so much of that. The idea of being a Smart Kid as a way to assert yourself, I found super helpful on one hand, but later realized it also bred all this internalized ableism. Have you had that experience?

Yes. Even if given the opportunity to bring up disability in class, I probably wouldn’t have known what to do or say — because, again, I never came across disability in books. I didn’t have the language for it outside of medical diagnoses. So for the longest time, I thought I wasn’t somebody to be concerned with unless I had a medical issue. Other than being able to do well in class, I should just blend in and not bring it up.

Remember the article you wrote a while ago about being angry? I related to that a lot. I was a very snarky, snappy kid. I always felt like I had to be on the defensive and I never understood why. It wasn’t until seventh grade that my social studies teacher pulled me aside and was like “You know, instead of getting in trouble for all these comebacks that you have, you should join Mock Trial. Channel your energy towards that.” And eventually I became a lawyer, so. [Laughs] Here we are.

“I never came across disability in books. I didn’t have the language for it outside of medical diagnoses.”

Was there anything specific you read about disability that led you to where you are now?

Absolutely. I always rave about her book and refer to her as my “disability mom”: Don’t Call Me Inspirational by Harilyn Rousso.

I love that book, it’s so good!

Yes! For anyone who hasn’t, Harilyn Rousso is a woman with cerebral palsy who was born in New York in the ’40s, and this is her memoir. It’s an interesting book because it’s not your typical memoir — there are poems, there are snippets of dialogue she has with strangers, it’s sort of a collection of moments from her life. She explores the typical disability narrative: the disabled person as inspirational figure, just because they got out of bed and managed their day.

I actually came across the book because I was running a mentoring program for disabled young women, and was looking for something we could wrap our minds around. For a lot of these women, it was their first time thinking about disability identity and feminism, and what it means to be a woman. So I found Harilyn’s work, and I liked the way she talks frankly about being a disabled woman: about sex, masturbation, being married, learning how to drive. It was the first book I read where I was like “Holy shit, this is exactly my life.”

What is that relationship like for you — especially as a woman of color — between disability and your other identities? What does that feel like?

It feels like a mess. I am definitely still trying to figure that out. As a queer woman and a person of color, it’s strange. Oddly enough, I sometimes pass as white or Latinx, so I get a lot of things thrown at me that are not who I am. Going back to the idea of having control over my own narrative, I’m very much working on how my disability relates to my race, gender and sexuality. There aren’t a lot of examples out there. But I try to remind myself that because there are no other examples, I can be sort of free about it — it’s up to me to define.

I’m feeling good about it right now because it’s Pride month [laughs], but on any other day, it can be very challenging. Having that reputation as the Smart Kid, for example, and also being Asian-American, can feel like I’m feeding into the model minority crap. I think because education is something my family always stressed, the first, most ableist idea I was instilled with was “Your disability only affects your body and not your mind.”

I’ve gotten that one, too.

That was emphasized throughout my education. I swallowed it and clung to it. And it wasn’t until about three or four years ago that I realized how damaging that can be. This idea of the model minority, along the same lines, is damaging because people pigeonhole themselves into the idea of doing all the right things in school, getting a white collar job, being on top of their shit and not letting themselves fail or just be who they are. It’s now playing out as a lot of mental health issues and not feeling like you really deserve the things that you have.

I think there’s a hierarchy within disability that a lot of us play into without realizing it. But the more we’re talking about it, the more conscious I am of it. It starts with those of us who can visibly pass as “in the norm” with our bodies and however we present, and the hierarchy works downward from there. That idea makes presenting as a queer woman difficult. Having a disabled body and trying to mesh it with being queer — understanding that the disabled body is rarely sexualized — creates a lot of tension. It’s difficult because we’re always trying to figure out where we stand, and I think sometimes in the queer world, we don’t allow a lot of flexibility in the way bodies present. With my body, it’s never the same day to day; I just don’t move the same way as I might have yesterday or the day before. And the pressures of always trying to present a certain way are challenging. I just wish there was more openness between the two worlds.

“I’m very much working on how my disability relates to my race, gender and sexuality. There aren’t a lot of examples out there. But I try to remind myself that because there are no other examples, I can be sort of free about it — it’s up to me to define.”

So where did you go after Harilyn Rousso’s book?

I basically Googled every name that she mentioned. And that was how I learned about Corbett O’Toole, Simi Linton — My Body Politic taught me a lot about disability history, especially in terms of institutionalization. And I also learned a lot about the politics of acquiring a disability versus being born with one.

What else would you recommend that people read if they want to get better at disability politics?

Since I’ve started teaching, I’ve tried to put as many disabled writers of color as possible on the “required readings” list. And one of my favorite blogs is Anita Cameron’s, Musings of an Angry Black Womyn. She’s always at the front lines of every political conversation. I would also recommend Geek Love by Katherine Dunn. It’s not really looking at disability in the traditional sense — it’s more sci-fi, and pride in being a mutant — but there’s still a lot of that power and hierarchy.

Also, for those interested in more disability rights and the present-day fight, I would recommend Good Kings, Bad Kings by Susan Nussbaum. That involves a bunch of kids who are institutionalized in Chicago, and they kind of break out of the institution. And in terms of disability and race, I would recommend The Story of Beautiful Girl by Rachel Simon, which takes place in the late ’60s/early ’70s and is about a young disabled white woman and a deaf African-American man who fall in love and are institutionalized. It follows them on this 40-year journey.

Sandy with Simi Linton, author of My Body Politic

It’s great that you can recommend books across all genres with not-terrible disability portrayals — because I feel like nondisabled authors especially can go to a weird place sometimes.

Yeah, and usually because they center characters around their disabilities. They’re described solely in that context — maybe they’re in a wheelchair, or they have some kind of tic or something. Authors who are not disabled tend to pick out one stereotype and just wrap the character around it. It’s very one-dimensional, and they serve maybe one or two plot purposes of “overcoming” or “inspiring.”

Jodi Picoult, who I kind of can’t stand — I know I’m probably wading into contentious waters right now, because she is very popular — does this a lot. The entire family drama wraps around a child with a disability. You hear about the sacrifices, but you never hear about the actual disabled kid, what they want or what they’re actually saying.

When I’m not reading for work or for teaching, I don’t really read for disability. Like right now I’m reading Murukami, which I do about once a year, and I’ve been into graphic novels. I just finished the Paper Girls series, which is about 12-year-olds who fight alien monsters while delivering newspapers in the suburbs of Cleveland. It’s interesting and refreshing to be in this time period where authors are resisting in their own way. I also just finished the graphic novel American Born Chinese, which was amazing. That opened a whole bunch of floodgates in my mind.

“Reading has allowed a lot of empathy on my part, but also an awareness of the empathy I should have for myself. Because I’ve become more aware of disability as a political identity, that has been a very empowering act: to finally be okay, and sit with it.”

Would you ever write a book of your own?

I would like to — I think that would make four-year-old Sandy very happy. It’s always in the back of my mind. For a few years, I did have a blog where I focused on disability, and that was kind of the first time since I was a kid making up stories that I focused on my own life. I recognized that there were a lot of online spaces dominated by parents of kids with disabilities, and they’ll just kind of write whatever they want. Or it was from the perspective of teens using the space to vent, which was very much needed. But there was nothing from a young adult at the time, looking back on what worked and what didn’t. It was one of the first times I wrote very honestly about my disability — and because of that, I think a lot of my blog entires come off as a little inspiration porn-y. I look back on them now and I’m like “Ugh, this is so cringe face.”

I don’t know if my future book would be about disability, necessarily, but I would love to write a book someday. I think as a reader, it’s really that aspect of being curious about other people. Reading has allowed a lot of empathy on my part, but also an awareness of the empathy I should have for myself. Because I’ve become more aware of disability as a political identity, that has been a very empowering act: to finally be okay, and sit with it. So now I’m at the point where I’m reading new material and adding to those layers to my identity. The next step is “How do I communicate that to my family and my friends, and the students that I teach?”

Queer Crip Love Fest: Who Will Be My Emergency Contact?

We’ve covered a lot of ground so far on Queer Crip Love Fest, including relationships of every shape and size. But what happens when a relationship ends? How does love look and feel in the shadow of a breakup, and how does disability impact that experience?

Katie, a PhD student living on the West Coast, has a lot to say on the matter.

I originally responded to you with my magical story of two queer crips who met and found love and acceptance in each other. Now that my story has a surprise ending, I wonder how much that acceptance and love was externally motivated. Because we crips spend so much time defending our right to exist on this earth, insisting that we have the same rights to romantic comedy love stories (that don’t end in death) feels like a stretch. Breakups are never easy and they usually involve ableism. That can be difficult.

Read on for the value of communal love, the joy in queer crip outsider status, and the problem with that whole “emergency contact” box.

When we first talked about your recent breakup, you mentioned that for you, breakups have usually involved ableism. Can you tell me more about that?

With my recent breakup, I don’t remember a lot of our last phone call, but what I can remember stands out because I didn’t recognize the person who said it. She said she didn’t want to depend on the social safety net and was concerned that I would end up back on disability and dependent on her, which would be both a financial and intellectual setback for the relationship. Of course that was one explanation she gave out of many, and I can’t claim to this day to understand exactly what happened or what her real intentions were. I can’t presume to know. But this was the same person who shared vulnerability, family, tears and difficult medical decision-making while I spent months with her in the ICU.

What I can say is this direct mention of my disability and its capacity to strip me of financial independence, daily functioning and intellectual rigor hit buttons so fragile I’m not sure I knew they existed before. In retrospect, it seems only natural to push the most painful buttons we can imagine because we’ve felt them ourselves. That was where the magical love originated in the first place: the depth of understanding, shared language of experiences and lust and love born of watching one another’s resilience and successes.

The other side of that coin, though, is that you know someone’s vulnerabilities and are able to get to them immediately.

“Internalized ableism is not a character flaw — it is a result of living in this society, and the best we can do is try to recognize it, identify it and mitigate it.”

And vulnerability is such a sticking point, for exactly that reason. Has your disability affected how you’ve dealt with the fallout, do you think?

None of us show our best selves during a breakup. They bolster our defenses and beg us to preserve our ego. And again, I can’t stress enough how much this is magnified when we see daily threats to our life-saving healthcare, or able-bodied doubts that our crip lives are worth living. Internalized ableism is not a character flaw — it is a result of living in this society, and the best we can do is try to recognize it, identify it and mitigate it.

You know, “Who will be my emergency contact?” is a question that comes up after any breakup in my life. It’s a proxy for a lot of other questions, because each relationship is supposed to fit into that model. No one from my family of origin goes in that box; my family didn’t even go to see me in the hospital when we were on the same coast. Instead, I use the box for my villages of dykes, queers, crips, freaks, and the occasional open-minded normie along the way. Because that’s the village who will cushion my fall.

“Love is community over individual for me in a world that was not built to house my body or heart.”

Can you think of an example?

Recently, thanks to a case of crip burnout, I decided to “just go with it” when a specialist wanted to do a procedure on me despite admitting to never having heard of one of my systemic diseases. The idea of dealing with insurance and finding a suitable second opinion was too exhausting in my mind. A close crip friend intervened, telling me — in colorful language — just how bad of an idea that was. Then she asked for my insurance information and proceeded to call other offices. I was so moved by her care for me; ultimately it stirred up my own sense of deserving good care, and I found a new provider.

That’s a true friend.

My disabilities land me in the ER not infrequently, and if I’m hospitalized, crip friends are the ones who show up to visit me, humor me and my off-color jokes, be in solidarity when I need to advocate for different care or accommodations, and laugh with me while I laugh at myself and my stash of forms from non-compliant patient-ing. Fair-weather friends get strained out real quick when you have several chronic illnesses. Superficiality doesn’t stand a chance; things get real, fast.

Lovers come and go and illness flares and friendships are strained. Only conceptual community is forever. Love is community over individual for me in a world that was not built to house my body or heart.

“Queer crip love is politicized whether we like it or not.”

How has community love been most valuable for you?

Queer crip love is politicized whether we like it or not. When the personal is political, our ableist world is ready to deepen any chasm that might have been opening up already. Personal trauma becomes pretty inevitable. When a relationship ends, I often regret that I could not have preserved it for queer crip family love instead; it’s less intense, but also less subject to abandonment.

I think that for both queer and disabled people, community can provide the support that lots of outside people in our life can’t or won’t, whether out of fear or some other reason.

Living with disability teaches us to find our own purposes for existing, resisting, relating and loving. We get a crash course in finding external sources or ego boosts. My recent breakup was a refresher in this lesson. Regaining my sense of self as something in my core that cannot be as vulnerable to systemic, widespread ableism has been a powerful experience, strengthening my prior sense of self. It takes too much energy to build up ego walls against capitalism, ableism and everything in society that can dictate a sense of worth. And if we are counting our spoons, we don’t have that kind of time!

“Queers and crips don’t fit in this society, by intention, so we come up with creative workarounds. We think differently by necessity.”

In light of the breakup and everything else that’s happened, how do you feel about romantic relationships right now?

I do believe that intra-queer-crip relationships are valuable and beautiful things. Of course, race, class, family support, gender identity, and tons of other factors shape how we experience them (and the world). I am acutely aware of how my class, race and educational privilege interact.

Right now, I’m finding myself deepening my love of myself and my entire communities through loving another queer crip. We’ve named body parts and bionic parts, laughed at ill-timed medical events, and given few-to-no fucks about external gazes. Queers and crips don’t fit in this society, by intention, so we come up with creative workarounds. We think differently by necessity. In my experience, that thinking outside of the proverbial box extends to romantic and sexual lives.

“We reaffirm our existence and resistance when we love each other.”

And finally, the behemoth of a question I ask everyone: what does love mean to you?

Love is messy and unconditional, honest and forgiving, indescribably joyous. Love is my cat climbing into bed with me for a fluffy cuddle when I need to hide out from the rest of the world for a bit. At this point in history, when our existences are threatened by policies and hate crimes and many of our communities suffer from deprivation of care, feelings of worthlessness, and traumas, we reaffirm our existence and resistance when we love each other.

Queer Crip Love Fest: More Seen Than I’ve Ever Felt

I write you from the hallowed halls of Terminal 3 at O’Hare International Airport, awaiting my return from the annual woodsy queer bonanza known as A-Camp. We had a glorious time workshopping, Variety Night-ing, and fleeing sudden thunderstorms, and now I’m prepping for the notorious Camp Comedown. This volatile period often involves physical illness/rebellion by a body you’ve neglected for a week accompanied by feelings of heightened disgust with the patriarchy, and it can be a rough ride. So to help ease us back down to earth, this week’s Queer Crip Love Fest features a bona fide A-Camp love story.

Katie (left) and Al (right)

Al is “a fat, disabled, terminally ill, cis, Jewish lesbian” who works for a women’s geek interest site and had this to say about her partner, Katie:

“My partner and I met at A-Camp in 2015. We were instantly obsessed with each other, but she pursued me much more. We Skyped constantly, then we started dating, and now we live together! There is this moment, it’s just a second, between when we’re acting serious and when she’s acting like a wild monkey. She tries to make me laugh, to force me to enjoy my life. She is radiant light and I want to be blinded by it.”

May this sweet recounting of camp romance guide you through a truly disorienting time. Hang in there, friends.

Tell me about your work!

I am co-editor of the games section of WomenWriteAboutComics.com. I started the section almost three years ago and recently hired my co-editor (who is INCREDIBLE) because my day job had become so demanding. Now I’m mostly handling the logistical aspects of the section (soon to be its own website), while spending my days as a Director of Communications for a really great nonprofit, OneTable.

How’d you get into gaming? As a relative outsider, I’m always curious how women in gamer and geek culture navigate that space.

I’ve been gaming my entire life. My parents were very young and very poor. My dad was still a teenager when I was born and he had a Super Nintendo from one of his friends. As soon as I could hold the controller I became addicted to gaming.

For a long time I wasn’t really cognizant of how treacherous the waters can be for gamers who are not cis hetero white dudes. I played mostly one-player games and wasn’t interested in joining the world of online multiplayer. It was when I started dating other gamers that the full scope of the gaming world came into focus. I suddenly became afraid of trying out certain games and of telling strangers that I played.

That’s part of why forming a games section at WWAC was so important to me. We have our own stories to tell and our own needs that are often neglected in mainstream gaming journalism. I’ve written for some of the bigger sites and they want a specific style and particular stories. I’ve chosen to not engage in toxic stuff and to help carve out space instead.

Nailed it.

I want more of you and your partner’s origin story! It’s so cute and gay!

So! My partner, Katie, and I met at our first A-Camp where we were cabinmates. I had very recently been diagnosed with Antisynthetase Syndrome, which can be a devastating disease. It had been made clear to me that I might not make it to 40 years old. I was still processing when I got to camp and was looking forward to sort of a temporary reprieve from what had been a grueling diagnostic process.

The first night at camp we talked about what we wanted to leave behind for the duration of the trip. I told everyone about my illness, and about my fears surrounding it. I remember clearly announcing that I was not interested at all in finding someone to date. And, in an abridged version of this story, Katie and I both eventually left other relationships after months of daily Skype calls to be together. For the first while I was flying back and forth from Chicago to D.C. to spend a weekend here and there with her. It was never super stressful. We just fit. And our Skype dates went well into each night.

When she moved across the country to live together, it just worked immediately. We’re very similar in ways that matter, even though almost none of our interests overlap. (We’re also both slobs, which is important. Having just one slob in a relationship can be a struggle.)

At our second A-Camp, I spent a lot of the trip in bed. The travel was very hard on me, I’d gotten much sicker, and I ended up with a migraine. Katie reported back to me on all the activities I wanted to know about and was great at checking in without making me feel like I was bringing down the mood. Then, in our cabin’s Feelings Circle (totes normal), I shared that I was alarmed by how fast my lungs were breaking down and when it was her turn she told everyone that she was in it (our relationship) for good for all the eventual sponge baths and until I drew my last breath.

Like… she’s the love of my life. She makes me feel more seen than I’ve ever felt.

Did you go to camp expecting to meet someone? Did you feel like there was pressure to do that once you got there?

There was no pressure to find a relationship, but, for me at least, there was more opportunity for queer romance than I’d ever been faced with before. I had fully planned to just have fun and maybe make friends.

“I am learning to deal with my illness. It is swift in its changes to my body and my ability to do the things I once did. I am having to learn to be gentler with myself, to let go of things I do not want to do.”

I’m curious about the interaction between your relationship and your disability, especially its progressive aspects. Popular media like Me Before You romanticizes death as a form of liberation from disability, leans heavily on the idea of a nondisabled savior as part of that process, and goes on to make hundreds of millions of dollars worldwide. How do those kinds of narratives make you feel — do you relate to them, do you feel they represent you, or is it the opposite? How have you and Katie talked about those issues?

This is such a complicated and interesting question, and absolutely one of my favorite topics. My version of my disease is affecting me in a couple of ways: my lungs are failing, my muscles are breaking down, and I am constantly fatigued. Since it is a progressive, chronic illness, I am becoming “more” disabled with time.

My mother has been disabled for most of my life. She’s battled with a lot of complications of diabetes since childhood and became blind when I was very young. I grew up thinking disability looked like a very particular thing. I hadn’t yet met all of the incredible people I know now who live with disabilities and are happy and healthy. We didn’t have access to a lot of the resources that I now know exist (and that are at risk under the current government).

So no, I don’t see myself in any media narratives. Characters are given terminal illnesses either to kill them off or miraculously save them at the last minute. It’s never clear that sometimes terminal illnesses take a long time to kill you, that there’s so much life and joy and pain and fear and fun and frustration between diagnosis and death. Katie and I talk about this a lot — specifically about how much becoming increasingly dependent on her is going to suck, but also how much I love being alive.

How have you and Katie negotiated the reinvigorated healthcare battle? My girlfriend and I have had to have some Real Talks about where we’ll be able to live and all that, and it can get kind of scary, as I’m sure you know.

Well, it’s made me terrified of losing my job. Which, due to the progressive nature of my disease, eventually I will. I don’t know what we’ll do then. It’s a dark spot, a black hole. And while being together makes the terror less lonely, it doesn’t stop being terrifying.

I am learning to deal with my illness. It is swift in its changes to my body and my ability to do the things I once did. I am having to learn to be gentler with myself, to let go of things I do not want to do, to give up some of my favorite things (anything not on the autoimmune protocol diet, for example) in the hopes that it slows the steady march of my disease.

Also, I am happy. I’m in love. I love my jobs. I know one day we’ll need to move out of our dream apartment because I won’t be able to walk up the eight steps to the door. I know one day I’ll have to give up most of the work I am energized by because I won’t be able to stay awake long enough to be “productive.” And I know that I might be facing that day much sooner than I hope I will. Yet my life is so full of reasons to celebrate and to despair. You know, it’s life. I wake up each day in pain and discomfort, knowing it is likely the best I will ever feel. It makes me feel loved when I know that’s enough. That even though I can’t promise her a long life together, our time is enough.

“We live parallel lives that we choose to tangle together with love.”

Do you face a lot of misconceptions as a disabled and terminally ill person in a relationship with someone who is not? What is one thing you wish people understood about your dynamic?

Ha! I think people who don’t know us at all sometimes imagine she’s in a caretaker role. That’s simply not the case. We’re both busy people with very different and time-consuming interests. We live parallel lives that we choose to tangle together with love. Honestly, if anyone’s naturally the caretaker it’s me, not her. This year she declared to our group of close friends that she planned to be there until my lungs finally failed felt like the only moment in the entire world.

So what does love mean to you?

Oof. Well, I think it’s meant many things to me over the years. I have a lot of emotions and 90% are love. In my early twenties I fell in and out of love often, always desperate to remain friends and stay connected with each of my exes.

Then I was in a series of more serious, more long-term relationships and love seemed to mean that I continued to choose the other person and invest in our relationship. Now, not only with Katie, but in all of my relationships and friendships, I believe it’s something else. It’s a comfort and a choice, but also a surplus. I feel so whole on my own, now that I’m growing more into my skin, that love is a happy bonus.

Queer Crip Love Fest: We Make it Radical

On Sunday night, my girlfriend and I were at the airport (my favorite!) when a security guard asked us to clarify ourselves.

“Are you two related?”

“No, girlfriends.”

“Okay, so you guys are friends.”

“No, girlfriends. Like —”

Before I could confirm that she meant “dating each other,” he was already down the jetway, explaining to his colleague that “she’s traveling with her friend.”

Tale as old as time, really — especially for queer women. And if you add disability into the mix, you wind up with a dynamic that a surprisingly large number of people flat out fail to understand. That’s why I was excited to talk to Jax Jacki Brown, a queer crip activist, performer, writer, feminist, public speaker on LGBTQIA and disability rights, person I have long admired from across the internet, and proud co-owner of one of the sweetest and gayest relationship stories I’ve heard.

Photo by Breeana Dunbar

She had this to say about her girlfriend, Anne:

“We’ve been together for two and a half years, so of course we U-Hauled pretty quick and we have a cat. She’s a non-crip, but she’s an awesome ally. She’s read all the disability studies texts I own (which is a lot!). We talk about disability and queer rights, and she deeply engages. She gets it as much as someone who isn’t a crip can. Allyship is really core to our relationship. We spent 10 of our first 11 days together, and in true lightning-fast lesbian fashion, we’ve been together ever since.”

Enjoy our conversation on disability pride, how a wheelchair can be like a lover, and proof that poetry really does get you the babes.

Tell me more about your girlfriend!

Her name’s Anne and we officially met online, on a queer dating website. But she had seen me perform poetry at a local queer venue a few months previous to me cruising her there. She says she thought I was super cute and funny with my queer crip poetry, but apparently during the break when she was trying to summon up the courage to come say hello, I had a bunch of people around me (it was my local queer venue so I knew people) and she thought “there’s no way she would be single.” So when she saw me online and I inboxed her she was like “oh, it’s the babe from poetry.” So yeah — poetry can get you the babes!

We talked for like a week online, then she got really drunk one night and sent me her number and we had a cute phone chat, then we went on a date and really haven’t looked back since! To be honest, in true queer form, we basically spent all of our time together from the start, but we did wait almost a year before I moved in with her and her cat. And that was almost three years ago now!

She is a proud fat, femme feminist. She is generous, kind, witty as hell (she loves a good pun), sexy and just easy to love. My queer relationships prior to this one have always been high drama, so it took some getting used to being in a relationship that just worked.

Now we live in the suburbs in Melbourne, Australia, with our cat, Boo, in an old rundown house that we are trying to fix up. It sounds super normcore and boring, but it’s not; we make it radical! It’s just super lovely. It’s my safe space, my home, and she is my space to land when I’ve been out in the world doing scary, boundary-pushing queer crip activist work.

Was she familiar with disability politics before meeting you, or did you introduce her to it? How’d you go about that if it was new to her?

This is a great question! So if I’m being honest, it took me awhile to talk to her about the social model of disability, which she didn’t know about before we started dating, and the reason it took me a while — whereas normally it’s one of the first things I talk about when I’m getting to know people as friends or lovers — is precisely because I really liked her. So it meant a lot to me that she understood how important my disability politics are and what my politics are, and I guess because I was already invested, there was a lot riding on “the conversation.” It took me a good couple of months to tell her about the social model and disability rights, even though she used to ask me about it. I mean, she knew that I was speaking at things and vaguely what it was about, but that was it.

“It’s knowing that she has my back — that not only does she get it, she will fight for it, she will fight with me. She loves me just as I am.”

Part of my reluctance and fear around “the conversation” had to do with my parents’ ableism. I feared having someone I really liked dismiss me in the same way they have. I mean, logically I knew she wouldn’t, because she has a deep understanding of power, identity and social justice. But that’s the effect of ableism — the fear was still there.

When we did finally talk about it, she said something like “I’ve never heard of the social model, but of course the world and society influences how you experience your body and interactions and places.”

Was there a moment where you knew that she really “got it” and that you were safe and understood, or did it evolve over time?

It’s a combination of all the moments where something ableist happens where she is there giving me that look that says “I’m here, I’m seeing it too, you’re not alone.” It’s in those moments after something ableist happens and we come home and I debrief with her, and she is able to articulate clearly and with rage why what happened was fucked.

One example, which I’ve written about before, is when we were at a dinner party and people started talking about how of course you would abort disabled fetuses. People were agreeing as though it was the only logical option, and then my friend finally turned to me and asked what I thought. So I tried to articulate why what was being said was deeply ableist and hurtful, and Anne clearly and calmly added to my points so I wasn’t the only voice in that room holding the weight of speaking up. Then we came home, she lay in bed and held me while we talked about what happened and asked what she could have done better, how she could have been there for me more in the moment, even though it was already beautiful not to feel lonely and isolated in those moments of speaking back to ableism.

The other example that springs to mind was last year when we went home to see my parents. They said a bunch of ableist things, and when I just couldn’t be in the room with them anymore — I just couldn’t continue to clearly and calmly explain why my disability is not a tragedy — she stayed and tried to talk to them and help them through the grief they are still resolutely stuck in. Then she came and held me and reassured me that the way that I think about my body, my identity, and my politics is valid.

It’s knowing that she has my back — that not only does she get it, she will fight for it, she will fight with me. She loves me just as I am.

“There’s this assumption that even if you’re calling each other ‘love’ and ‘honey’ and holding hands and behaving as a couple that of course you can’t really be lovers or partners — you must be friends or family, because a person with a disability can’t have a sexuality, let alone a queer sexuality.”

I love that allyship in all directions is core to your relationship. Can you tell me more about what that looks like?

To be honest, I think that she does a lot more ally work in the relationship than I do, but maybe that’s because ableism is more overtly present and unless publicly talked about than other forms of oppression. I think I am a good ally to her femme identity, but I could perhaps do better with allyship around fatphobia. I feel like our queer feminist politics are pretty aligned, and we back each other up and go on cute feminist dates to feminist events.

Do you deal with a lot of misconceptions as a mixed-ability couple?

People somehow assume that she’s amazing just for being with me, that she contributes far more than I that I do to the relationship, that she must earn more than I do, that I should be forever grateful, that one day she will wake up and realize that she is with a person with a disability (like somehow she hasn’t noticed) and leave me for someone “better” — and of course that person is an able-bodied person. Oh, and we get the comment all the time “you two look like sisters!” to which we’ve started saying “yeah, sexy sisters!”

You know, there’s this assumption that even if you’re calling each other “love” and “honey” and holding hands and behaving as a couple that of course you can’t really be lovers or partners — you must be friends or family, because a person with a disability can’t have a sexuality, let alone a queer sexuality.

I mean, you know all the stuff. I’m sure you and your girlfriend get it too.

Yup. Can confirm.

“She says ‘I like how you have a sound, that’s different from how everyone else sounds. I like that I can hear you coming home, wheeling up the ramp, moving about the house, and know it is you.'”

I’m really interested in your relationship to your wheelchair, and how that factors into your relationship with Anne. Can you tell me more about that?

I love my chair; it’s a part of me, it’s a part of my identity, it’s a part of my personal space. It’s how I move through the world, it’s how I am perceived, it’s almost an extension of me. It’s not just an object; it’s almost like a lover. I wrote a poem about it around five years ago called “Do you have sex in your wheelchair?”

To be honest, I’m tired of my current chair — she is getting old and I really need a new one, but the process in Australia is so arduous and long that I always put it off until they literally start falling apart.

Anne is always very respectful of my chair; she’s careful when taking the wheels off, putting it into cars, or carrying it upstairs to be kind and gentle, because she knows how much it means to me, and also that I only have one, so it’s precious. She says “I like how you have a sound, that’s different from how everyone else sounds. I like that I can hear you coming home, wheeling up the ramp, moving about the house, and know it is you. It is familiar and beautiful. I like how you move in your chair, and how your body has a rhythm and sway to it that is just yours.”

What has the process of cultivating disability pride been like for you?

I’m sure you’re familiar with Laura Hershey’s poem “You Get Proud by Practicing,” where she says:

Remember, you weren’t the one

Who made you ashamed,

But you are the one

Who can make you proud.

Just practice,

Practice until you get proud, and once you are proud,

Keep practicing so you won’t forget.You get proud

By practicing.

I think it is so true — practicing your pride in a society that tells you that you should be ashamed is an act of resistance and resilience. As the late and great Stella Young said, “This is possibly the most important thing anyone will ever tell you. The journey towards disability pride is long, and hard, and you have to practice every single day.” So I make sure I practice and surround myself with people who value and love me. I’m also profoundly lucky to do work in disability rights, and get paid for most of it these days.

Being queer and disabled has allowed me to live life outside the box of social expectations. It’s enabled me to deeply question society, bodies, power, identity, and to work out what I really think is important to value, what I’m really passionate about, what I believe in. It’s enabled me to become unapologetic and proud.

I try and proudly practice calling my body home, to truly inhabit my body, to feel what it feels like to live inside these muscles that bend and curl, and to feel proud of it, and no longer ashamed. This is queer crip pride.

Photo by Eddie Raft

So with all that in mind, what does love mean to you?