What Long COVID Taught Me About Mutual Aid

This is Autostraddle’s “How To Survive A Post(?)-COVID World” series. In some areas, COVID restrictions are lifting, but regardless of how “post”-COVID some of our individual worlds might feel, a pandemic and its lasting effects rage on. These writers are sharing their struggles and practical knowledge to help readers survive, heal and thrive in 2021.

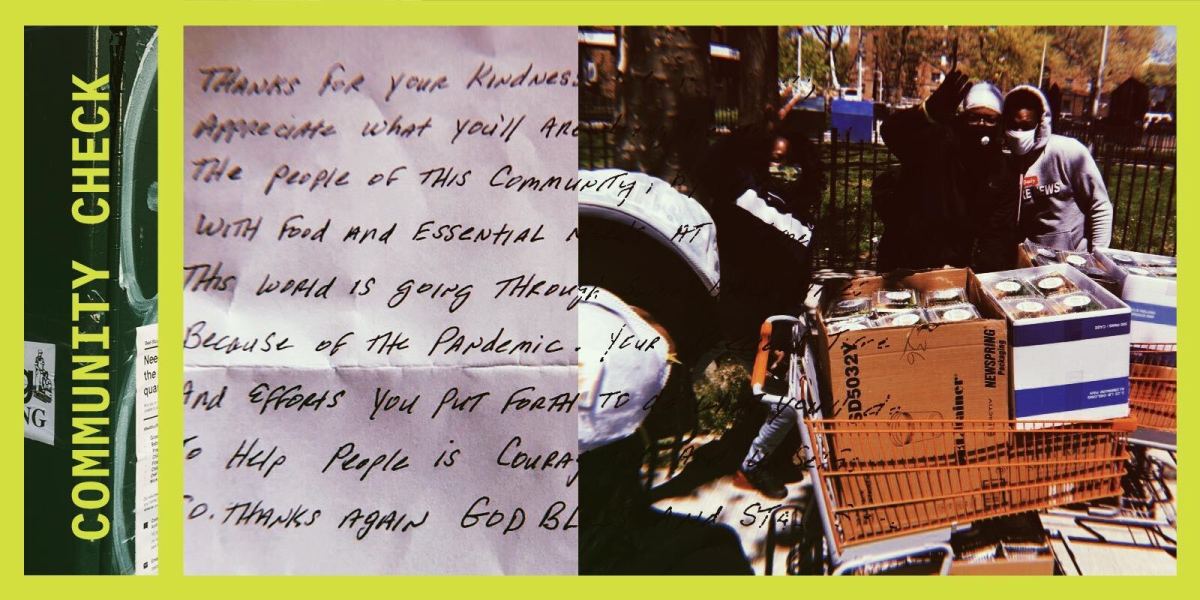

On May 1, 2020, I was tested for COVID. This was part of routine testing across our Minneapolis social service agency following positive COVID cases among our clients. My positive test was a surprise to me — I didn’t have any symptoms beyond what I thought was pandemic-anxiety creating shortness of breath. I completed my ten days of isolation at home and returned to work. It was remarkably unremarkable. And — given that two weeks later George Floyd would be killed, the city would ignite in flames and hundreds of us would take over a hotel to get unhoused people indoors and off the militarized streets — it goes without saying that the “asymptomatic” COVID case I had was quickly forgotten. Instead, we were creating mutual aid networks to get supplies to neighborhoods whose groceries stores burned down. We activated community defense networks to protect homes and respond to fires. We raised thousands, then millions of dollars for abolitionist efforts around the city.

It wasn’t until around July 2020 that I started noticing what I would come to understand as some combination of Long COVID and post-viral fatigue. I started wearing a pulse oximeter when things like walking to the kitchen sink would leave me breathless and spike my heart rate. I missed two days of work after walking my dog one July afternoon because I got so sick afterward. I was experiencing shortness of breath; heart palpitations; tachycardia; night sweats; changes in taste, smell and appetite. Even the smallest exertions required recovery time. Every single entry I wrote in my journal during the month of July references my fatigue.

This pattern of vague, diffuse symptoms that left me completely wiped would continue for months to come. An entry in my journal from October 14th reads, “Well, I think a lovely evening drinking with my brothers brought on a relapse of symptoms. I’ve been off work Monday and Tuesday this week and I’m feeling like crap today. I wish I had started keeping a symptom log earlier in this process because it feels silly to try and start one nearly six months in”. It continues with a list of symptoms: short of breath, chest pain/ pressure, shaky hands, flushed face/ itchy skin, fever feelings/ chills despite no fever, brain fog, palpitations (“not racing heart, but pounding heart”), muscle weakness/ heavy limbs, headache (“dehydration? COVID?”), fatigue (“as usual”).

Despite this list of symptoms, no doctor or test found anything wrong. My blood work was normal. The Zio patch heart monitor I wore for two weeks was normal. In September, I took myself to the ER thinking I had deep vein thrombosis due to swelling in my ankles and a severe calf cramp that lasted almost ten days. My CT scan and the ultrasounds were normal. Every additional COVID test I got was “not detected.” With a litany of normal tests, it was hard not to question my own sanity. Am I actually sick? Am I making it up? Do I really even actually feel that bad? And yet, I was still missing multiple days of work per month and the time between sick days was getting shorter and shorter.

I finally collapsed in January 2021. I had been sliding down a hill picking up speed toward this inevitable collapse for a while, but I just hadn’t been able to admit it to myself. It wasn’t until I literally shit my pants at work that I finally admitted defeat and requested a short-term disability leave. January 29th, 2021, was the first day of what would end up being a three month medical leave.

In May, I returned to work part-time. It turns out that the medical leave wasn’t actually enough to cure my Long COVID symptoms, but it did give me enough space to reflect on which COVID lessons are worth carrying forward into the post(?)-COVID world. Going back through my journal entries, notes in my phone and blog posts from the last year, it surprised me to realize that the same things I need in order to manage my Long COVID are the things we all need for the future we are creating: mutual aid, seasons of receiving along with our seasons of giving, self-care that is directly connected to community care, less work, body trust and disability justice.

If you’ve never had a health crisis like this before, it’s quite humbling. I’ve never been good at asking for help, but when you’re so collapsed that you literally can’t manage, you’ll be amazed at how much help you ask for and how the help you ask for still won’t be enough. I had always believed in mutual aid, but I can’t say I had fully comprehended the mutual part. Mutual aid is mutual because, as much as I hate to admit it, we all need more support than we can provide ourselves. I had to ask for help not just once, but repeatedly for months, and I’ve come out the other side as a mutual aid evangelical. People ordered me dinner — not once, but weekly; delivered me meal boxes; brought my flowers and sent me care packages. The more we can think about our personal resources as resources that are meant to be shared, the more we can get our own needs met in our own seasons of receiving; our “winters,” as Katherine May calls them in her book Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times.

I spent weeks in collapse mode, unable to even consider “active recovery”. I watched eight seasons of Supernatural in the first three weeks of my leave and showered only three times in that same timeframe. And do you know what I would find myself thinking about in moments of quiet? Work. How fucking miserable is that? It’s like even though I knew I was off work, my body didn’t know I was off work. It occurred to me that there is a part of my body that has been made to feel unsafe by the chronic demands of work under capitalism. Intellectually, I know I feel safe at work and, arguably, it sounds ridiculous and even dangerous to throw around phrases like “feeling unsafe” so loosely. But my body’s autonomic responses to stressors don’t know the difference between “real” threats and perceived ones. The pervasive demand by society to Do More left me feeling trapped and even — as my therapist sometimes suggests — traumatized by insidious pressures to work, even as my body continued to wear down. In a March 4th blog post, I wrote, “Tonight I did a really casual search for ‘social work’ across a couple of job boards just to see how it felt. I started to cry.”

I did eventually stop watching Supernatural and turn toward healing. It turns out that the diagnostic and treatment process for Long COVID, even in a very mild case such as mine, is practically a full-time job. My process has included a post-COVID doctor that I’ve seen every six weeks since February, an MRI of my brain, a neurology appointment, chest x-rays, an overnight sleep study, multiple sleep appointments, a referral for a neuropsych exam I still haven’t had, a pulmonary function test, a pulmonology appointment, weekly physical therapy, weekly occupational therapy and, coming up, voice therapy for my damaged vocal cords and breathing muscles. My occupational therapist prescribed me fatigue management tools like blue light glasses and note-taking, an 8:30pm bedtime, sunglasses in the grocery store, smell and taste training and more. My physical therapist prescribed me a maximum heart rate of 120 (now, after two months, 140) beats per minute, thoracic stretches, breathing exercises and 20 minutes of walking every day. The sleep doctor prescribed me iron supplements to help with restless legs — supplements that also cause digestive distress. The neurologist told me nothing was wrong “except for the obesity.” The pulmonologist prescribed me an inhaler and suggested that it will be awfully hard to lose the weight I gained when my heart rate needs to stay so low.

Throughout this entire process and as of this writing, the short-term disability claim I initiated in late January has never been approved. I had zero income during my leave because the insurance company still doesn’t have the right medical documentation to prove that I needed to be off work. Even with relatively good health insurance, healthcare is prohibitively expensive and disability insurance benefits (not that I ever fucking got them!) only cover 60% of wages. It was here that the mutuality of mutual aid really came into high relief. After years of facilitating things I call “barnraisers” on Twitter, I needed my own barnraiser. I created a Plumfund, emailed a pointed ask for help to 36 people and shared my ask on Twitter. In four days of fundraising, my community put together over $12,000 for my partner and me. Caring for myself and asking for that help allowed me to get back to the business of recovery and has kept me connected to my community, even in my season of receiving.

I returned to work in May — not because I was physically or spiritually ready to go back to work, but because that was when my short-term disability benefits were due to run out (not that I ever fucking got them!). And, in order to potentially qualify for long-term disability benefits, I had to return to work at least 20 hours per week. If I’ve become an evangelical for mutual aid during this health crisis, I’ve become a zealot about the need for all of us to reduce how much we work. I learned from Long COVID (and my occupational therapist) that my body is my compass and also my captain. If I don’t submit to my body, it will shut the lights off regardless. From my March 19th blog post: “My body has been very clear with me in it’s absolute refusal to participate in work. I said to a fellow disabled friend yesterday that the level of bodily refusal to even entertain the *idea* of work feels so strong that I actually feel like I will be abusing myself if/ when I have to return to work.” My body gives me very clear cues (fatigue, malaise, brain fog, tinnitus, body pain, nausea, hand tremors, etc.) when I exceed my capacity. While I used to be too stubborn to listen, I am listening closely now. My body no longer cares about what is expected of me by society, about how my bills can’t get paid while I’m trying to prioritize my health or about any obligations or guilt I feel toward my job. I am no longer in control of this body (was I ever?); it is in control of me.

My sense is that many of our bodies are reaching this point. A year-plus of pandemic living has revealed just how much our bodies can bear and the end of what we can bear no longer. People are tired, and our bodies will not be forced against their wills. We are all long overdue for a transformation of our working conditions, and our bodies know this. Your body might not have reached outright mutiny the way mine has, but it will — give it time. It has become an essential part of my thoughts to find a way out of this way of working because working like this will literally kill me if I don’t. Becoming disabled by the world is radicalizing, and I already thought I was pretty radical.

Perhaps if you take all these things together — the COVID, the mutual aid, the community care, the body trust, and the urgent need to divorce our health and living from our ability to work — what you get is what disability justice movement has been trying to tell us forever: our bodies are the site of that we carry. As Aurora Levins Morales puts it in Kindling: Writings on the Body, “What our bodies require in order to thrive, is what the world requires. If there is a map to get there, it can be found in the atlas of our skin and bone and blood, in the tracks of neurotransmitters and antibodies.” Looking forward to the world we are shaping (hat-tip to adrienne maree brown) beyond the pandemic looks pretty similar to the radical roots all bodies require for living.

Art by Hannah Mumby

Disasters as Experiences of Care: How to Pack a Go Bag, Give Mutual Aid in Crisis, and Rethink Queer Preparedness

When I was a teenager, my parents prepped for the y2k crisis. Anticipating a global meltdown on January 1, 2000, they bought a farmhouse on land in rural Virginia. On most weekends in 1999, we left our white suburb in Richmond for “the y2k house” so my dad could plant and hand thresh wheat, hunt deer and squirrels, put up shelf-stable supplies, and fix up the bonus room in case more people needed shelter.

This apocalypse was born when programmers predicted global chaos resulting from a software bug. Older computers abbreviated the year in dates to two digits—so “2000″ becomes “00.” This meant that on the first day of the new year, some systems could act as if we were back in the year 1900. Mainframes, medical systems, and government tech were all at risk, experts said. My parents agreed.

I believed what I was told. And yet the chores I was assigned at the y2k house felt impossible. I didn’t want to help my mom double-dig vegetable beds in the front yard. I hated helping my dad organize buckets of food in our basement storehouse. Ashamed, I hid in bed to write in my notebook. Ironically, my inner life centered on computers. I envisioned myself as a programming wizard and sketched the magical characters I roleplayed in chatrooms (ah, the wild early days of internet life!) on my PC at home. I could see no place for myself amidst our family’s preparedness fantasy, so I associated myself with our narrative of threat, while also imagining myself uniquely empowered to fix it.

The eve of the rollover arrived. Prince’s “Party Like it’s 1999″ played over and over on the radio. We watched the New Year’s celebrations on TV, wondering if the power would cut midway through, plunging us into darkness. The lights stayed on, though. We switched them off ourselves when it was time for bed. Since the dates changed at different times around the world, my parents said, the shutdown might not happen for a while. But time passed, and our new millennium arrived with a surprising lack of fanfare—or tragedy. We waited a day, and then another. We listened to the news. Nothing changed. Eventually, my parents packed up the Dodge pickup truck and we made our way home.

Was I relieved? Not exactly. My future still felt shapeless, as it had been before the world was supposed to end. The fact that there had been no apocalypse didn’t change the fact that I was queer. What did change for me, though, was my perception of safety, self-sufficiency, and readiness for disaster. I want to live a life that isn’t defined by fear, I told myself, even if that means living under dystopia.

Years later, COVID-19 hit the U.S. in early 2020, and a few months after we entered lockdown my friend Nina Budabin McQuown, an editor, writer, and producer, asked me if I’d co-host a podcast. The name would be Queers at the End of the World, and the idea was to explore stories of apocalypse, dystopia, and survival through the lens of queerness. Yes, we would be discussing the very narratives of paranoia my parents had fed me throughout my childhood, the stories that had informed our family’s preparation for a false apocalypse. And through those conversations we would try to make queer art.

As little as I wanted to revisit the psychic bunker that had defined my coming of age, I also desired a way to tell my version of that story. So I agreed to the project, and Nina suggested we begin by talking about go bags. Also known as a bug out bag, a battle box, or a personal emergency relocation kit (PERK), a go bag contains the supplies—food, water first-aid, tools, maps, light, masks—you need to survive for several days in a crisis. Even though we agreed it was a smart idea, especially during COVID-19, neither of us had assembled one yet. “I don’t do preparedness,” I said to Nina. But could we change that? Was openly facing disaster, violence, and a climate-changed future something I could do?

When we interviewed organizer Kalaya’an Mendoza, who works with the justice collective Across Frontlines, he told us he didn’t like the term “prepper.” He explained, “The thing I see a lot, especially in the States, around disaster preparedness is the hoarding of supplies, or ‘gotta get all my guns,’” he said. “But the only thing that has allowed our species to survive all of the trials that we have experienced, from colonization to plagues, is building community with one another.”

Mendoza, who identifies as queer, Filipinx, hard of hearing, and as an immigrant, seems nothing like what I imagine as a “prepper.” Nina and I found him on Instagram, where one post in his feed depicts Mendoza serving as a bike marshall at protest. He’s wearing a DIY hot pink onesie made from a safety vest and short shorts, and definitely looks like someone I wish I was cool enough to be friends with. Later, another post depicts Mendoza’s go bag, providing a detailed breakdown of the supplies he’s put inside.

In Mendoza’s view, preparing for an apocalypse isn’t that different from getting ready for a protest. When we asked him for an alternative term for preparedness work, he said, “I like to think of the folks who are looking out for the community, one another, folks doing mutual aid, as protectors.” This term, which Mendoza says comes from the native organizers at Standing Rock, poses preparation as healing justice, something we can all participate in together.

Later, I asked Mendoza about the origins of his interest in safety. How, I wondered, could anyone be obsessed with something I so powerfully wished to forget? Mendoza related a memory of the Loma Prieta Earthquake, which struck when he was a child. “I distinctly remember how our community—we lived in a small apartment complex—made it really fun for the kids. All the parents came out with their barbecue grills and we cooked for one another.” In his memory, I realized, disasters are linked with experiences of care.

I don’t mean to imply that Mendoza thinks crises are fun. Rather, I think he has a nuanced understanding of what dangerous circumstances can offer us. I told him that, in my past, fear seemed like it was the enemy, a force to be battled and resisted. Mendoza replied, “I invite folks to think about fear as a teacher. Fear teaches us how to be safe. How to survive.”

Cate Steane, who runs Make it Happen Preparedness Services in Santa Rosa California, also connects the idea of apocalypse with potential healing. This ability, to see opportunity in moments of crisis, seems shared among queer folks for whom preparedness is an obsession. Steane comes at preparedness from a different angle, consulting with larger businesses and essential businesses like homeless shelters and in-home care services on how to rebound after a disaster. But her approach was still all about giving care.

“For an organization,” Steane said, “you have to assume that people’s first impulse is going to be to take care of their families.” Since the continued operation of a business relies on staff returning to work quickly, Steane tells those businesses to support the safety of their employees’ families. “I encourage businesses to give their employees materials on how to develop a family plan. And then offer incentives, where if they bring back in a completed family plan, you give them a starter emergency kit.” Like Mendoza, Steane approaches preparedness by acknowledging community ties, and inventing ways to strengthen those ties in the face of disaster.

For me, though, the best part of talking to Steane was learning about her alternate identity, the Safety Freak. She told me, “I was part of a hiking group that would go on camping trips in the summer and part of our tradition was a talent—or lack of talent—show. Somebody had called me ‘safety freak’ and I’m like, I can hang with that.” She put together a skit, arriving on stage as a superhero in a cape, a helmet, and a leather belt stuffed with supplies. Safety Freak became a recurring character who appeared at Steane’s trainings to explain the dimensions of disaster readiness through comedy. How perfectly queer, I thought, to celebrate this obsession with safety by getting into costume. Maybe I can hang with that too.

The threats Mendoza and Steane focus on are different, even though their love for safety is similar. Mendoza talked about mutual aid during COVID-19, and the state-sanctioned violence he had witnessed at BLM protests in New York City. Steane was interested in the earthquakes and fires that put Californians in danger every year. This difference helped me see why go bags were important to each person. Preparing one isn’t some general queer obligation. It’s a tactical response to a specific threat, and it puts you in conversation with your region, your community, and your future.

If you’re ready to build a go bag of your own, Cate Steane has a guide to go bags and stay supplies on her website. I’d also recommend checking out the New York Times climate risk map Steane shared with me. It’s a good basis for identifying the most pressing climate change-driven threats to your local community. Finally, Mendoza suggested including in your bag “something portable that makes you feel safe — emotionally.” This could be a book, a stuffed animal, or a family photo. “Because when I talk about safety and security,” Mendoza said, “it’s not just physical. It’s also emotional, mental, and spiritual safety and security. That’s the only way that we’re able to move past trauma and towards healing.”

Steph Niaupari, a founder of the Washington D.C.-based food and body liberation movement Plantita Power, also touched on the notion of an internal go bag when we talked. I’d sought out Niaupari because I wanted to talk about community work that wasn’t specifically focused on disasters — but still met head on the threat of dystopia, chaos, and danger. When I asked them to speak on their concept of preparedness, Niaupari said, “I see it more as what skills do I have, or what skills do the people in my group or pod have. We ourselves are our own go bags, because we’re going to figure it out wherever we go. As we have been.”

When they formed Plantita Power in 2019, Niaupari sought to create a community agriculture space where QTBIPOC folks could feel respected. But gaining access to land in D.C. was nightmarish. “The process behind it, the bureaucracy, is ridiculous, and it takes years, and you have to have the connections in order to do it.” Besides, Niaupari added, creating harmony in any private space is inherently fraught. “I wanted to make sure we weren’t replicating the violence we had experienced in other gardens,” they said. “It came to a point where we said let’s just stay at your space. Let’s create a garden in your backyard, on your porch, wherever it may be. And that’s how we started with the collective gardens.”

What would have happened if, in the late 90s, my family had built a community garden instead of a private bunker? As Niaupari said, gardens are not utopias. But I do imagine a world where, when the next disaster hits, I have a keener sense of who to give support to, and how—and who I can lean on when I’m facing grief and chaos. I’m realizing the heart of preparedness involves knowing, and really believing, that you are not alone.

At the end of my conversation with Niaupari, we ended up talking about this cart used by folks in their community to distribute resources at BLM protests—food, water, and even binders. Niaupari, who models for gc2b, was able to secure a supply. At that event, the sign on the cart read, “Water for the revolution, food for resistance, and free binders because we’re fucking fabulous.” When I said that this cart resonated with my musings on go bags, Niaupari let me know I wasn’t the only person inspired by it. In fact, the cart is going to be featured in Syan Rose’s forthcoming illustrated oral history of queer and trans resistance, Our Work is Everywhere (Arsenal Pulp Press).

It’s tempting for me to call Niaupari’s queer cart a “go cart,” but I actually think it’s critical to keep the two things separate. Preparedness might begin with a go bag, but it’s sustained through efforts like Niaupari’s, and those of the other queer community safety leaders I talked to in order to understand what being ready really means. I think, ultimately, it’s something that queers are already pretty good at—as Niaupari said, “figuring it out.” This is not about lingering in paranoia. It’s about being fucking fabulous, together.

When I think about preparedness, part of me will always invoke the “prepper.” Like Steane’s safety freak, he’s become this outsized character, an apparition who helps me understand my relationship with paranoia, isolation, and the hoarding of supplies. A gun-toting sheriff, this guy cleverly anticipates dystopian chaos (because masculinity!) and stands behind the fortified walls of his compound, deciding who will be let in and who will be deemed a monster.

Lately, I’ve been building a compost bin for the community garden on my block in New York City. And much as I’d like to avoid encountering my bearded specter as I enter these grounds, he’s inescapable. Even if my parents didn’t always resemble this awful fellow, he’s part of our history. I think about him when I plant vegetables, and when I dig my fingers into soil. Facing what he represents is a challenge, but when I do, it helps me see my future. I’m no longer occupied with compounds, and which side of the wall I’ll end up on. Preparing is something we will do together, as a community. As Mendoza says, “We keep us safe.”

Worried Your Vote Can’t Protect Reproductive Rights? Mutual Aid Can (and Does)

Four years since the election of President Donald Trump, the worst fears of reproductive rights advocates were seemingly realized with the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, cementing a 6-3 anti-choice majority to gut access to reproductive care and potentially even criminalize abortion. Naturally, Barrett’s confirmation was followed by reinvigorated calls for voting as the sole solution to the crisis we now face, to prevent even more dangerous judicial appointments on the federal level, and abortion bans on the state level.

Voting can serve as critical damage control — we know a President Joe Biden would support funding for reproductive care and appoint only judges and Justices committed to reproductive rights. And up and down the ballot, plenty of candidates and ballot measures go beyond reducing harm and make real, positive change, especially on the local and community levels.

Yet, many of the crises we’re being warned about with this new 6-3 conservative Supreme Court majority — discrimination against LGBTQ folks, people struggling to afford health care if the Affordable Care Act is gutted, and, certainly, people not being able to have abortions — already exist. From abortion funds, to legal defense funds, to mutual aid networks, the solutions already exist, too, due to the work of people who have long felt their communities are left behind by elected officials, and denied the full actualization of long-standing legal rights.

Across the country, mutual aid networks have long put in the work of moving wealth, and creating funding and logistical arrangements for people to afford abortion care and contraception, as well as transportation, lodging, and child care to reach these resources. In a country where 90 percent of counties lacks an abortion provider, funds have created the infrastructure for low-income people to cross abortion deserts, or regions where one clinic serves over 100,000 people of reproductive age. Some funds have even created special resources for trans people who face added barriers to reach abortion and other sexual and reproductive health care, as well as legal support and other resources for minors and young people to get care, too.

Abortion funds across the country last year supported 56,155 people seeking care, all amid a backdrop of unprecedented state-level abortion bans and restrictions being passed. Several funds in different states reported collaborating to help people travel across state lines to get care, and for funds in some regions, the majority of clients served were people of color. Throughout the crisis of COVID-19 this year, funds have spoken out about how much more urgent their work has become, especially as more people have lost their jobs, savings, or insurance, and all the existing barriers to get care have only worsened.

Groups like this have existed since before Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, and adapted their work to new political realities following the decision, through bans on coverage of reproductive care, rampant legislative attacks and closures of clinics, and even the continued criminalization and punishment of people who have abortions or lose their pregnancies, and need legal support. Amid COVID-19 and the shuttering of clinics across the country in recent years, community advocates and aid networks have helped educate and facilitate crucial access to abortion pills, which are FDA-approved and allow people to safely end a pregnancy at home without the necessity of traveling to a clinic.

Mutual aid and community care have always existed as a response to the devastating inevitability of state violence. After all, state violence is more than incidents of racist police brutality — it also encompasses the government’s failure to ensure access to basic resources like health care and especially reproductive care, most often for the poor and communities of color. State violence certainly encompasses government policies that deny people bodily autonomy and coerce their pregnancy and reproduction. The inextricable connection between violence and the state, especially for people of color, has led many to be dubious about looking to the state and elections for easy solutions, and instead, create solutions in their own communities outside of the government.

Because of these long-standing mutual aid efforts, the infrastructure to address the crises we face today is already there. To make a real difference, we should invest in what already exists, and the people and groups who have been doing the work.

Following the confirmation of Barrett to the court, like we saw after the confirmation of previous Justices who threatened Roe and other human rights, many social media users shared plans to hoard emergency contraception and birth control pills, or start crowdfunding for others’ abortions and travel across state lines, as well as legal fees if needed. But rather than personally try to reinvent the wheel and divert attention and resources from people who have long been doing the work, we should listen to their expertise on how we can support the work they’re already doing.

And for starters, on top of financially contributing to and volunteering with funds and other mutual aid networks, we could also simply not hoard basic resources like Plan B, which already can be costly and inaccessible, and would become even more so in scarcity.

Participating in elections, and especially elections like this year’s, will always be critical to the fate of the country and its most marginalized — after all, elections and voter suppression are what pushed us to this very point of reckoning. With the Supreme Court poised to potentially uproot life as we know it in America, voting by itself might fix some things, but it can’t fix everything.

Investing our money and effort into community care can go further than just relying on elections and institutions that have always upheld a status quo of oppression. None of us can do everything, or single handedly ensure everyone gets the care they need — but we can all find and contact our local funds, and learn about ways to volunteer, either for their hotlines, or to help with transportation, lodging, child care, fundraising, and other needs. We have to do more than put all our faith into a system that’s working as it was designed to marginalize women, people of color, and queer and trans folks. Instead, let’s recognize the transformative power and potential of mutual aid and direct action, starting in our communities.

Portland’s Black Lives Matter Protests Prove the Power of Mutual Aid

Over the last few months, Donald Trump has repeatedly described Portland’s Black Lives Matter protesters as “sick and deranged anarchists and agitators.” Acting Department of Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf has decried the protesters as a “violent mob” of “lawless anarchists [that] destroy and desecrate property… and attack the brave law enforcement officers.” And Portland’s own mayor, Democrat Ted Wheeler, has denounced the protesters, accusing them of “attempting to commit murder” when they started a small fire outside of a police precinct.

It probably isn’t surprising that the protesters, many of whom have gathered in Portland streets for the majority of the last 110 nights — and have stopped only momentarily while air conditions are hazardous due to wildfires — describe themselves very differently than politicians and pundits do. But what may be surprising to outsiders is how tenderly the so-called “lawless anarchists” speak of each other.

Activist and We Out Here founder Mac Smiff addresses thousands of protesters outside of the Portland Police Bureau headquarters. Photo by Tuck Woodstock, July 22.

“It’s the most welcoming and caring community I’ve ever seen or been a part of,” says Jasmine, a frequent protest attendee. (We’re using a pseudonym for Jasmine to protect her identity.) “I truly believe that you could walk up to a Portland protest naked, hungry, and alone and leave with clothes, food, and comrades.”

Jasmine speaks from experience. Earlier this summer, as she walked to a protest, “literally the first two people I saw who were also in black bloc noticed I was alone and asked if I needed a group,” she says. “That night I got [free] food, medical care, supplies, and protest advice, all from complete strangers.” Weeks later, Jasmine still attends protests with the people she met that night.

Other protest attendees also speak highly of the free supplies provided both by individuals — several people have stories of strangers gifting them respirators shortly before tear gas rolled in — and by an array of self-organized affinity groups: The Witches, whose slogan is “we hex fascists,” often appear on the riot lines toting glowing wagons of water bottles, snacks, masks, and earplugs. PDX Shieldsmiths turn 55-gallon plastic barrels into DIY shields to protect against batons and crowd-control munitions. Portland Action Medics equip trained street medics with housemade eye wash, hand sanitizer, and chemical weapon wipes, used to treat the effects of tear gas and pepper spray. And, for a few glorious weeks, volunteer-run outdoor kitchen Riot Ribs served copious amounts of free food to protesters and passerby alike.

A mountain of donated food, water, and other supplies at Riot Ribs, a free, volunteer-run outdoor kitchen that fed protesters and community members throughout July. Photo by Tuck Woodstock, July 24.

These efforts (most of which, for what it’s worth, are organized by queer and trans people) are all real-life examples of mutual aid, a term coined by anarcho-communists in 1902 and re-popularized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mutual aid occurs when people work together to take care of each other as a community; it’s a simple concept that contrasts sharply with capitalism, rugged individualism, and other systems that most Americans are raised to idolize.

“As an anarchist, this is the kind of shit I live for,” says Rosie G. Riddle, an independent journalist covering the protests. “Total strangers bandaging wounded comrades [and] offering food, water, protective equipment. Dearresting folks; shielding downed people (again, strangers) with their literal actual bodies. Offering shields for free. Posting each others’ Cash Apps to get them taken care of. The community surrounding these protests is the reason I bother getting out of bed anymore.”

Portlanders unable to take to the streets have also created roles from themselves within the movement. Sarah, a grad student at Portland State University, quickly realized that they weren’t well-suited for marching on the front lines. Instead, they cofounded AccessiBloc, a coalition of volunteers who work with independent reporters to make their protest coverage accessible to a wider audience.

“It’s something that is close to my heart because I’m hard of hearing and have low vision myself,” explains Sarah, who also does accessibility work at their day job. “A group of us get in the [Twitter] feeds of journalists and add image descriptions and captioning so they can focus while on the ground doing the documenting.”

Through AccessiBloc, Sarah enjoys the same sense of camaraderie that other protesters experience on the front lines. Once, when Sarah injured themself, a fellow AccessiBloc member immediately volunteered to drive them across town to the doctor. And when Sarah worried about covering their medical bill, protest supporters on Twitter quickly mobilized to help.

“I was panicking because I’m a student and don’t have a huge income,” says Sarah. “While I was at the doctor, I tweeted out my situation. By the time I left an hour later, my bill was completely taken care of.”

Portland’s Black Lives Matter protests have been held daily since May 29 to seek justice for Black individuals killed by police. In addition to protesting for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, organizers — most of whom are Black, and many of whom are queer — have drawn renewed attention to instances of law enforcement killing Black Portlanders such as Patrick Kimmons and Quanice Hayes. In August, the increased pressure spurred Portland State University to disarm its campus security officers, two of whom shot and killed Jason Washington in 2018.

For most of the country, however, the Portland BLM protests only became noteworthy when news broke in mid-July that federal agents were using unmarked vans to grab protesters off the street. After national news outlets reported on US Marshals and Department of Homeland Security officers indiscriminately teargassing thousands of protesters night after night (and leaving protesters and press with lasting head injuries from crowd-control munitions), the federal forces promised to retreat from the front lines of the demonstrations, and national attention quickly faded once again.

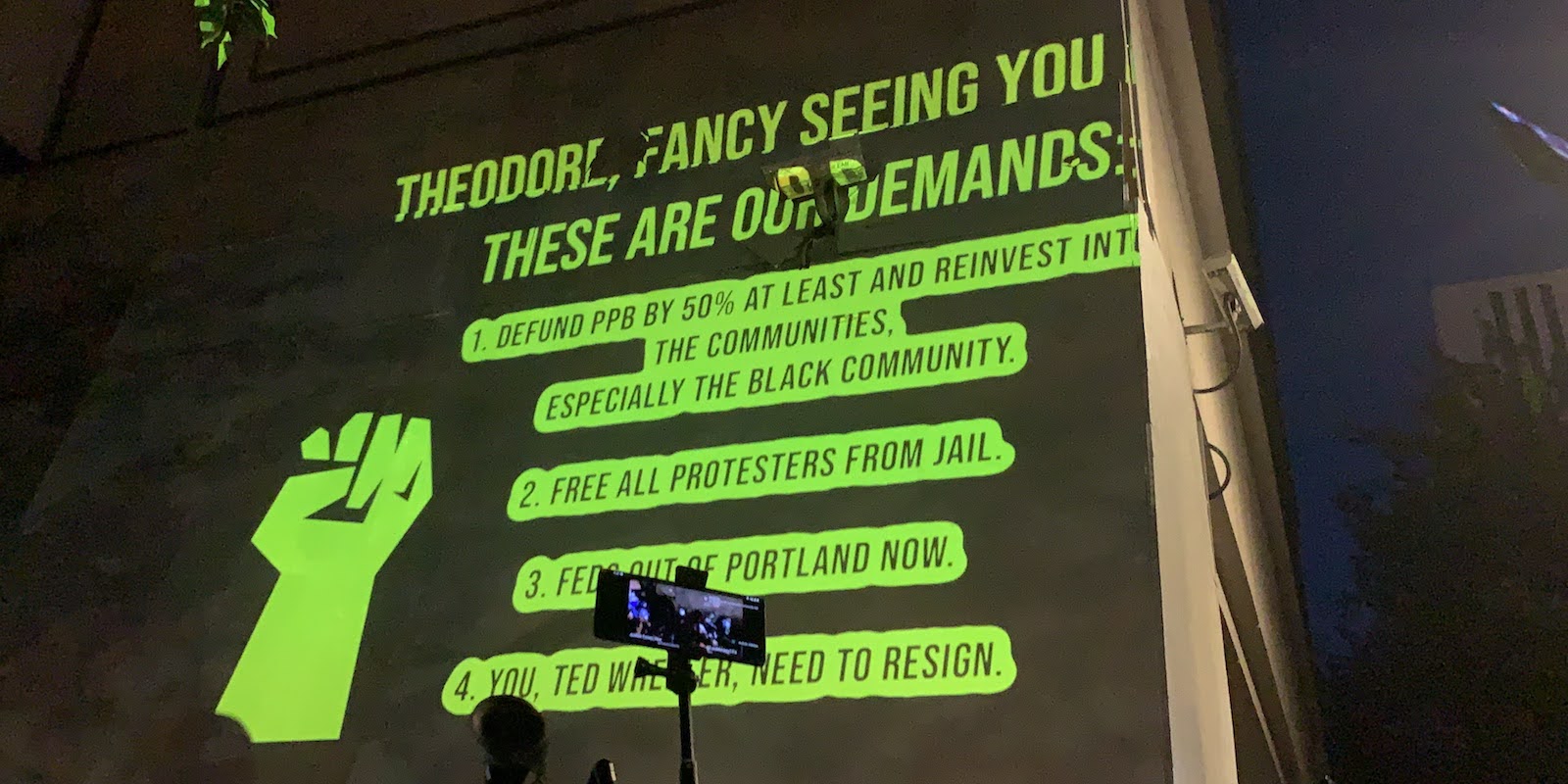

Many Portlanders also seemed to think that the protests would end once the feds retreated in early August. But despite national reporters leaving and crowd numbers shrinking, hundreds of determined protesters continued to gather nightly to decry police brutality against Black Portlanders. At this point, the demonstrators’ demands had become more specific: defund the Portland Police Bureau by at least 20% (although many protesters insisted on 50-100%); redistribute those funds to Portland’s Black communities; drop all legal charges against protesters; and remove Mayor Ted Wheeler from office.

Instead of gathering in downtown Portland, as they had since May, protesters began planning actions at other targets across the city, bringing chants of “Black trans lives matter” and “no cops, no prisons, total abolition” to the Portland Police Association union building, the local ICE facility, and the north and east police precincts. An average evening now includes dozens or hundreds of protesters (mostly young people in black bloc) marching and chanting — and often spray-painting, throwing eggs, or setting dumpster fires. A team of journalists and ACLU and NLG legal observers tag along to document the night’s events.

Protesters project a list of demands onto the wall of the Portland Police Bureau’s downtown headquarters as Mayor Ted Wheeler attempts to dialog with members of the crowd. Photo by Tuck Woodstock, July 22.

Unsurprisingly, the Portland police bureau invariably declares these gatherings to be unlawful assemblies or riots. Using a variety of tactics — pepper balls, tear gas, foam-tipped bullets, flash bangs, batons, and violent tackles, among others —the officers typically arrest up to 25% of the crowd (sometimes including journalists, medics or legal observers) and chase the rest into dark residential neighborhoods. As law enforcement tries to disperse the crowd, protesters work together to protect each other in various ways, from creating a wall of shields to using leaf blowers to disperse tear gas.

“I was shot in the ribs with a less-lethal ammunition,” says Maddy, a protester. “The response was immediate — someone with a shield ran in front of me, my friends helped me walk away and then escape the ensuing bullrush, and medics arrived to help as soon as we could stop running.”

Countless protesters have stories of strangers offering eye flushes (useful for recovering from tear gas) and other medical care in times of crisis. They also share instances of being physically pulled to safety as police ran towards the crowd.

“The officers ran out and pushed us up against a wall, telling us to move,” says Maddy, recalling another recent incident. “Protesters began climbing the wall, simply because there was nowhere else to go. I heard someone behind me say ‘I’m getting you out of here,’ and a complete stranger lifted me by my waist like a sack of potatoes, over the fence, and in the clear.”

“I had no idea who it was or where they went, but I will forever remember it,” she says. “The fact that someone looked down and saw this tiny five-foot protester in black bloc and thought to physically lift her to safety.”

After more than three months of continuous collaboration — first providing mutual aid at the protests and later, as wildfires ravage Oregon, caring for evacuees and other vulnerable community members — Portland’s community of left-wing protesters still rarely know each other’s names. For personal safety, protest attendees often refer to each other by twitter handles or nicknames like “Beans,” “Bulba,” “Antifa Hot Dog,” and “Revolution Daddy.” Nevertheless, they’ve become closely bonded by common goals, mutual aid… and shared trauma.

Many protest attendees report feeling permanently changed by their experiences, and not always positively. “We’re all going to need therapy after this” is a popular half-joke among protesters, often uttered while listing new symptoms of post-traumatic stress. And yet, those same protesters often feel reluctant to take a day off from the front lines.

“One of the reasons being away from the protests is so difficult is because you’re forced to face a lot of the trauma and PTSD symptoms that you don’t necessarily feel when you’re on the ground,” independent journalist Alissa Azar wrote in a recent tweet. “Jumping and flinching at sudden sounds; turning your head when someone gasps because you’re worrying riot cops are about to storm in from behind you and brutalize people, even though you’re nowhere near any kind of action… [that’s] not something everyone can understand.”

Protesters work together to create a protective shield line, holding their ground as federal officers fire pepper balls in their direction. Photo by Tuck Woodstock, July 21.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that many protest attendees now struggle to connect with friends and family who haven’t spent time on the front lines and don’t engage with the protests online. After all, the vast majority of Portlanders have continued to move through their lives as if the protests aren’t happening — a choice that can make traumatized protesters feel alienated, angry, or abandoned. “There’s this rift, or a feeling that they aren’t being understood, or a new impatience with people — like ‘how can you still act the same when all this has happened?’” explains Cata Gaitán, an independent journalist in Portland.

While Cata emphasizes that they’re not a scientist, they nevertheless have a theory about what’s been taking place: “I think protesters experience this constant loop of adrenaline/cortisol/serotonin from being angry, scared, and then momentarily relieved,” Cata says. “They are upset with cops; then they get chased, beaten, gassed, and shot at by cops; then they successfully escape those cops; then it all repeats itself moments later. And the people you experience that with become like a family, because you’ve gone through so much trauma together.”

“Family” is not a word that most people would use to describe a group of anonymous antifascist protesters. But after more than 100 days of protesters chanting “stay together, stay tight” and “we keep each other safe,” of them giving eye washes and safe rides to strangers, of them handing out free pizza and masks and hand sanitizer to anyone who asks, of them dearresting each other and bailing each other out of jail, it’s the only word that seems to fit.

Even Cata, the reporter, has a story of feeling like part of the family. As it turns out, they were trapped in the same rush as Maddy, where protesters began climbing a wall to avoid being kettled by police. As the officers drew closer, an anonymous protester reached out a hand to Cata. They wrapped their arms around the stranger’s neck and were lifted up and over the wall.

“That was the first ‘hug’ I’ve gotten in months,” says Cata. “I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment where I felt so protected and cared for — and it was by a complete stranger.”

“For three slow-motion seconds, I felt safe.”

This Relief Fund is Supporting LGBTQ Immigrants During the Pandemic and They Want Your Help

Graphic by Sarah Sarwar // Photo contributed by Raini Vargas

Mateo Sánchez Morales and Raini Vargas are two Bay Area trans activists who created a Covid-19 relief fund for LGBTQ immigrants. In this interview, Lia Dun talks to Mateo and Raini about how the pandemic has affected queer and trans immigrant communities, the power of mutual aid, and ways we can all show up for LGBTQ immigrants.

Can you describe your involvement with LGBTQ immigrant communities before the pandemic?

Mateo: As a transgender person and a second-generation immigrant, I feel close to both of these identities. For the past three years, I’ve worked with LGBTQ immigrants to attain legal immigration status. I’m also involved with mostly Spanish-speaking LGBTQ immigrant groups in the Bay Area that are rooted in community and mutual aid.

Raini: Both of us are openly queer and non-binary and have backgrounds in organizing and activism. I was born and raised in Anaheim, California, so many of the people I love and grew up with come from immigrant families. At my current job, I interact a lot with Mateo’s clients, and we’ve formed incredible relationships.

How has the pandemic affected LGBTQ immigrants?

Mateo: The pandemic has affected LGBTQ immigrants, not because it necessarily created new problems but because it exacerbated existing ones. A lot of people were already struggling to keep a stable job and pay rent and bills. Many people also had mental health conditions before the pandemic. After the coronavirus hit, people’s situations got worse. For people who had pending immigration cases, the courts have slowed down significantly, leaving them in uncertainty. Other folks lost their jobs. Many have found themselves in situations that are extremely unfavorable.

A lot of people have also had to start relying on technology for the first time to access services. I’ve had a lot of people come to me with questions about how to apply for unemployment. Even to me, these processes are confusing, so I can only imagine how difficult it must be for someone who has never used a computer or doesn’t have an email address. And that’s not even mentioning the language barrier that exists for a lot of folks. Sometimes if people need therapy and I want to refer them somewhere, I have to make sure that there are options aside from Zoom calls because that can be very challenging for them to use. A lot of funds also require people to have Venmo, CashApp, or PayPal to receive aid, and I have had to talk a lot of people through the process of downloading the app onto their phone and creating an account because this is all new to them. Many of the people we have assisted with our relief fund do not have electronic payment services and we have actually had to send physical checks to them or give them cash. It has been frustrating to see all these limitations and honestly very eye-opening because they’re things I hadn’t thought about before.

Why did you decide to start the COVID-19 relief fund for queer and trans immigrants? What were the challenges to accessing other forms of aid?

Raini: We officially started the fund on May 9th. Many of the people we know were working under-the-table jobs at places like restaurants, bars, and hotels. These were the places that were the first to shut down. When we referred people to resources, most, if not all, of the funds that we recommended were full or waitlisted. After realizing this, we decided to create a Covid relief fund specifically for queer and trans immigrants to pay for necessities like rent, groceries, utilities, phone bills, hospital bills, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and mental health services.

There are many issues to accessing aid through institutions. Many LGBTQ people and immigrants have an understandable hesitation in approaching and relying on institutional support. There is something very powerful about direct community aid because it allows people to bypass institutional barriers and access what they need. There isn’t a Board of Directors or a group of powerful people controlling what to do with the funds. It’s just community members supporting other community members.

How has it been working on a two-person relief fund? What have been the challenges, successes, and lessons learned?

Mateo: We realized very quickly that there is a lot of work that goes into putting together something like this.

First, there’s publicizing it — Raini creates the graphics that we share on social media often. We spend a lot of time drafting our updates and messages to the public. Then there’s the logistics and keeping track of everything — how much money we receive, who needs money, how to get the money delivered.

Raini: We also have to think about how we communicate with fund recipients and with donors. People like to be communicated with in different ways. Some folks prefer to talk on the phone, while others rely mostly on text or email. Also, we’ve already seen donors reach out and ask how their money was used. While this is completely understandable, it’s been hard to share updates with our donors while also constantly communicating with our recipients to make sure their needs are being met. Coordinating this and splitting the work between just the two of us has been the most challenging aspect of this.

Mateo: Yeah, it’s a lot of work, physically and mentally, to add on top of both of our full-time workload. We’ve also had to learn how to adapt to each other’s work styles since this is our first time working on something like this together, but generally, we work well together. Both of us come from low-income backgrounds, and now that we’re in better situations, we recognize the importance of using our resources to support others as best we can, while also acknowledging our own privileges — we have a lot of shared values, which makes our visions for the work we’re doing align.

Raini: Yes! Communication is never really an issue. We essentially read each other’s minds and finish each other’s sentences, so when it comes to working on our fund, we are always in-sync.

What are your plans to expand the relief fund?

Mateo: As our reach has expanded, we’ve been seeing an increase in donations but also an increase in people contacting us in need of assistance. We also know that a one-time payment is not enough, and many folks who already received aid need recurring payments. Although our initial idea was to support people through this really rough time, people need aid all the time, not just during the pandemic. Raini and I have talked about making more streamlined efforts to get people aid. We’ve been considering the possibility of a website and getting more people involved in this who can help our fund grow.

Raini: We’re mostly looking for Spanish speakers who are able to share our fund and also communicate with some of our recipients. We’re also looking for folks who have more experience with fundraising and coalition building. But we’d love to work with anyone, as long as you can show you’re devoted to the movement!

What are some other ways folks can support LGBTQ immigrants and/or undocumented folks?

Raini: Outside of donating, people should continue staying informed about attacks on immigrant communities. We are currently seeing the government rip apart and destroy the asylum system, proposing a new rule that would make it impossible for anyone to be granted asylum in the United States.

We also think it’s important for folks to become aware of their individual privileges. How does your citizenship status affect the way you navigate the world? As a white-passing queer person who was also born in the United States, there are certain aspects of my identity that are more protected than others in my community. It’s our responsibility, within the LGBTQ community, to continue to support and uplift our immigrant siblings.

Mateo: This fund started because we saw a need in our community that wasn’t being met. There are people in need all around us. If you see resources being shared on social media, share them widely with the people around you so that they can reach someone in need. If you speak another language, volunteer with organizations that serve populations that don’t speak English. If you already work in direct services, like therapy, keep in mind the populations you serve and do research about how to better serve your clients. Challenge policies in your workplace, neighborhood, or city that target these populations. LGBTQ immigrants are our neighbors, and there are always ways to offer help, even if it’s smaller, individual-level things, like checking on your neighbors and building trust with your community so that when folks need help, you’re better able to support each other.

If you’re an LGBTQ immigrant in need of aid or if you’re interested in getting involved with the relief fund, you can contact Mateo (@hijxdemimadre) at mateogael1818@gmail.com and Raini (@rainiv) at rainivargas.7@gmail.com To donate, you can Venmo Mateo directly (@M-Sanchez-Morales).

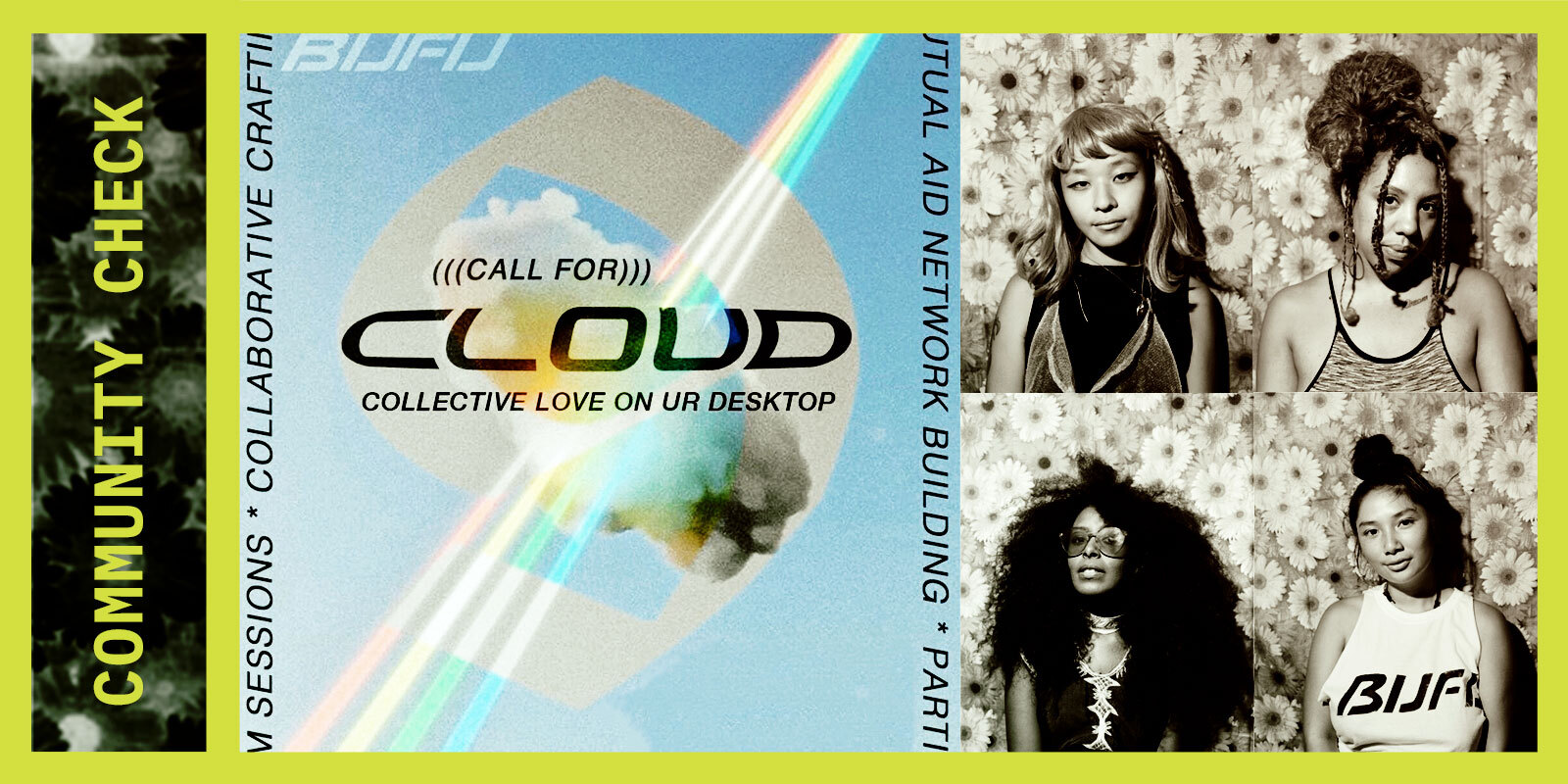

COMMUNITY CHECK is a series about mutual aid and taking care of each other in the time of coronavirus. If you would like to write about a mutual aid and/or community care effort happening where you are – either as a first person account or as a reported piece – please send a pitch to vanessa [at] autostraddle [dot] com with the subject line PITCH: COMMUNITY CHECK. We are particularly interested in publishing Black writers, Indigenous writers, and all writers of color; we are looking for stories from smaller cities, towns, and rural communities as well as big cities; we would really love to hear what mutual aid and community building looks like as we fight for Black lives and Black futures, work to abolish police and prisons, and fight against white supremacy.

How to Start a Mutual Aid Fund

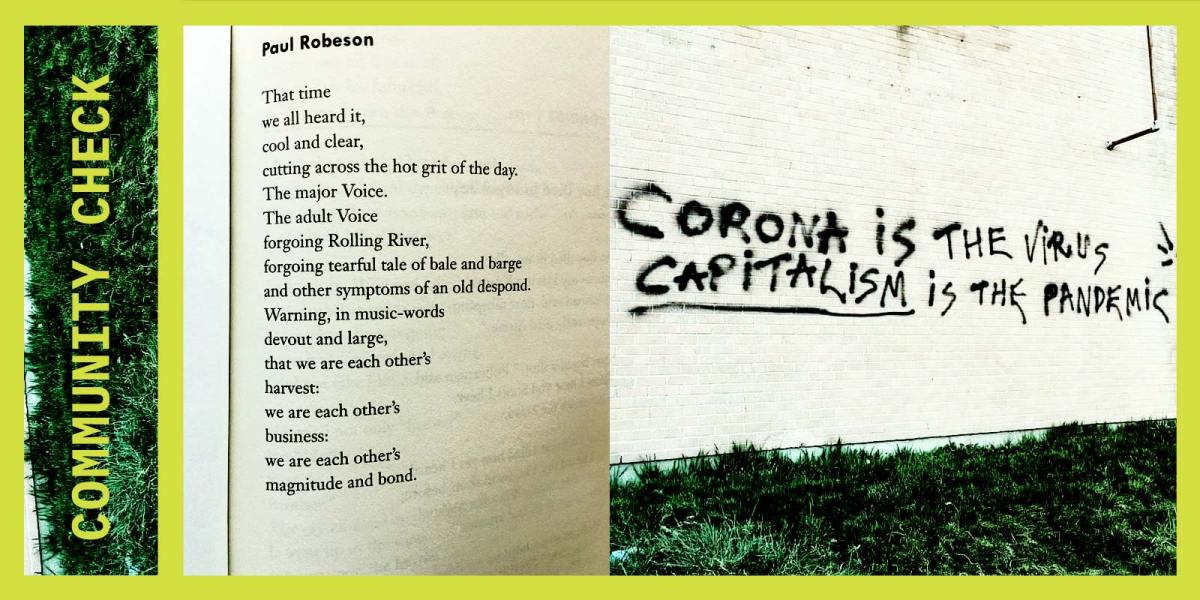

Graphic by Sarah Sarwar // Poem by Gwendolyn Brooks // Graffiti seen in Chicago, IL

On March 10th I launched Harvest, a mutual aid fund named after the following lines from a poem by Illinois Poet Laureate Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000): “we are each other’s / harvest: / we are each other’s / business: / we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” The fund has since redistributed over $10,000 and its straightforward structure has been adopted elsewhere so now there are multiple Harvests across at least three different cities.

To start, I mass emailed my community with $222 of seed money. Here’s what I said in a nutshell: make donations via Venmo and requests via phone by texting me the code word HARVEST, a dollar amount, and your Venmo (I switched to PayPal upon exceeding Venmo’s weekly spending limit). I sent a daily email with the available balance, which fluctuated dramatically, and often asked folks to fundraise because as closures increased so did the volume and dollar amount of requests. I received approximately seven texts per day, usually from friends of friends.

Some quick logistical tips:

- Team up with folks to create several Harvest funds that are each coordinated by 1-2 people

- Focus on the local, meaning where you currently live or your concentric circles of people (do not go viral – spread the word through word of mouth)

- Establish stewarding principles that prioritize those most impacted (BIPOC, disabled, and elder folks)

- It’s okay and will likely be necessary to put a cap on the requested dollar amount

While Harvest is indeed an example of “mutual aid” as opposed to charity, the idea for it didn’t come from studying solidarity economics but from my family of origin’s survival strategies. I am the descendent of immigrants and refugees who engaged in anti-capitalist practices (e.g., sharing and bartering) out of necessity. My aunts in particular have always relied on each other for resources that were inaccessible to them including child and elder care. As a queer femme of color, I have taken part in similar practices among my chosen family, especially fellow sick, disabled, and neurodivergent femmes. Together we have provided in-person and also remote support for one another with everyday tasks that meet our basic needs, post-surgery recovery, and more. The common denominator for these mutual aid efforts is people-to-people relations.

Harvest is likewise based on relationships rather than accumulated capital. For this reason, Harvest fund coordinators have encouraged folks to “organize your pod” or network of people you can call on for support and shared the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective’s pod mapping worksheet. Building what Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha calls “care collectives” is a core principle of disability justice and, more broadly, of radical interdependence. I say radical because interdependency challenges the rugged individualism underlying ableist ideology and capitalism, which thrives off disconnection. As adrienne maree brown recently wrote, to resist capitalism “spend less time consuming the internet, and more time developing relationships with real people with whom you share the tangible…and the intangible (listening, loving, dreaming, trusting, laughter, grief).”

https://twitter.com/redfishstream/status/1248989182854217730

The sustainability of Harvest hinges on “deep reciprocity,” in the words of Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, not debt. My emails stated: “multiple requests welcome, no questions asked [or application], and 100% confidential.” The fact that someone can access money immediately with no strings attached sets Harvest apart and is pretty extraordinary given the capitalistic way in which even non-profits administer resources. The fund redistributed wealth as one might gather and give away the fruits of a harvest. What makes mutual aid transformative is precisely how it functions outside of oppressive systems much like abolitionist responses to COVID-19 that organize toward a world without prisons.

https://twitter.com/monicatea2/status/1243779305915719680

I know that collective care is the future because it has made my past and present possible. We must acknowledge that mutual aid is not original—or optional—for chronically dispossessed people and therefore, always already political. Global histories of settler colonialism, racial slavery, and empire precede this genocidal time. Marginalized communities developed mutual aid and other collective care practices to go on living despite quotidian white supremacist terror. As Franny Choi’s poem puts it, “before the apocalypse, there was the apocalypse,” which brings me back to Brooks and the liberatory teachings of Black feminism. The only way out of ongoing state violence and into a new social reality is becoming each other’s business.

COMMUNITY CHECK originated as a series about mutual aid and taking care of each other in the time of coronavirus, inspired by the ways in which queer people came together in so many different ways to care for one another from the very early days of the pandemic. Autostraddle planned to publish the original series twice a week from May 12 – June 18, but we do not want to stop highlighting these efforts, so we are extending the COMMUNITY CHECK column indefinitely.

We are actively accepting pitches for the COMMUNITY CHECK column from today, June 18, 2020, onward. We will publish 1-2 COMMUNITY CHECK articles each month moving forward. We are particularly interested in publishing Black writers, Indigenous writers, and writers of color; we are looking for stories from smaller cities, towns, and rural communities as well as big cities; we would really love to hear what mutual aid and community building looks like as we fight for Black lives and Black futures, work to abolish police and prisons, and fight against white supremacy.

If you would like to write about a mutual aid and/or community care effort happening where you are – either as a first person account or as a reported piece – please send a pitch to vanessa [at] autostraddle [dot] com with the subject line PITCH: COMMUNITY CHECK. Please feel free to share this call far and wide.

Queens Center for Gay Seniors Creates Phone Check-In Project, Connecting LGBTQ Elders and Youths During the Pandemic and Beyond

Graphic by Sarah Sarwar // Photos contributed by Abbie LeWarn

When it comes to our center, we refer to our members as family, cheesy as it sounds. Queens Center for Gay Seniors, a program of Queens Community House, is a drop-in senior center in Jackson Heights, Queens. LGBTQ seniors and allies can take classes, exercise, and enjoy a warm meal. Many of our members have known each other from the Queens LGBTQ scene for years, and continue to support one another through the challenges of aging. Even on days when our center has no programming occurring, seniors still come to sit and talk with friends for hours.

“Being a gay man, I found myself having nothing in common and often isolated and unwelcomed at senior centers,” one senior wrote to me for this article. “At QCGS I was welcomed and at home amongst new friends. Gay seniors no longer need to be isolated without a place to be themselves and to feel comfortable among their peers.”

Isolation and depression become serious issues as we age and our center is the main tool for elders to combat these concerns. When the news came that we had to shut down all programming due to COVID-19, it was devastating. Our staff of three was left trying to stay in contact with 500+ members and scrambling to figure out how to connect meals back to seniors.

When the elder check-in phone outreach project started, it was only 10 volunteers making calls to a handful of members. We had connected with a professor at Hunter College who helped us build the initial group. Volunteers were responsible for informing seniors of the rapidly changing emergency meal policy. It wasn’t until we partnered with We-Work and NYC Dyke March that the project evolved and expanded. Our volunteer pool went from 10 to 150 people, all wanting to connect with LGBTQ elders. What started as a few emails changed into a full-fledged intergenerational network.

Seeing so many young LGBTQ folx come forward to help keep seniors safe and connected was moving. We had tried for years to create intergenerational programming with varying levels of success. It was often hard to reconcile differences to build lasting connections between youth and elders. These barriers, combined with the fact that American culture often ignores or forgets elders, made successful intergenerational work difficult. This group is dedicating their time to shift the intergenerational dynamic. The virus was tearing NYC apart at the seams, but through the phone project, our community felt more connected than ever.

Volunteers shared that they were relating to seniors on a multitude of topics, from LGBTQ movies to favorite recipes. Differences that once made this work so challenging felt small amid the crisis. Many were feeling degrees of isolation when this program started, so not only did seniors benefit, but younger LGBTQ members were able to feel a new sense of community. “I never met an elder queer person before. These calls gave me a sense of what my history was, and what my future could be,” one caller wrote.

Volunteers were also able to share important center updates and food resources. As the program took off it started to become abundantly clear that seniors were struggling without the center’s meal program. With the help of Green Top Farm, Love Hallie and Queens Together, we were able to form an emergency meal delivery service. The two organizations helped us fundraise to buy meals for seniors from vulnerable local restaurants. Every Friday a team meets to deliver meals to members throughout Queens. This food program has become a saving grace for senior health while the city works out gaps in its system. Volunteers making calls assess food needs and update the delivery team with the information needed to support our community directly. Without this team of volunteers making outreach calls, we never would have been able to reach the number of members we have today. These calls help make sure no member falls through the cracks and that our family can stay connected through this turmoil.

When asked about the project one senior wrote: “To me, The Queens Gay Senior Center is a place where I can be myself. I am able to feel comfortable and happy with people that are also gay. During COVID I was able to have food delivered to my home and weekly calls which took away a lot of stress. It means that someone is always checking on me to make sure that I am doing okay. Living alone during these very difficult times it has meant a lot to have them. With so much going on in the world today, I love and appreciate Queens Center For Gay Seniors.”

As we move through June, this incredible showing of support and care across generations makes us hopeful for what the future of the New York queer community will look like moving forward. The bonds we’ve built through this program feel uniquely strong and nuanced. I hope we can continue to develop a network that supports and celebrates all generations of the LGBTQ community.

COMMUNITY CHECK is a series about mutual aid and taking care of each other in the time of coronavirus.

MedSupplyDrive Relief Work Started with COVID-19, Now Includes Support for Protestors

Graphic by Sarah Sarwar

When the hospitals started sending out distress calls for PPE in mid-March 2020, I was electrified and searching for a way to help, so I responded to a call on social media from a volunteer organization called MedSupplyDrive for a regional coordinator in NYC.

In the blink of an eye, the efforts for gathering PPE in all of NYC on behalf of a national organization lay on my shoulders.

On day 1, it was just me and my partner Charlie. We cold-called and emailed hundreds of places, heart in mouth, praying for someone to be generous. And people came through, offering gloves, masks, and more. By day 3, we were still alone, and gloves needed to be delivered, but we had no car. I’ve been a distance runner for over a decade at this point, so I pulled on my running shoes and battled the wind along the Hudson River Parkway for a 14 mile-round trip. I returned home sore and exhausted, but I felt exhilarated. I knew we were making a concrete impact and helping the providers who keep this city safe. But we couldn’t do it alone, and I was tired of waiting for people to find me.

So, as I always do when looking for solidarity and support, I turned to my queer community. I texted my friends, put out calls in the Facebook groups which have been a safe haven for years, and asked for all hands on deck. The NYC queer community, which has housed me when I had nowhere to go, fed me when I was hungry, and held me through my worst traumas and losses, came through in a landslide. My inbox was flooded with offers of support, and within hours we had a driver team. We had folks driving from Manhattan to Far Rockaway to pick up single n95s, calling hundreds and hundreds of small businesses, giving money out of their own thinly-lined pockets. Our volunteer Tea, a queer tattooer and astrologer, mobilized the tattooing community and brought in massive amounts of medical-grade gloves that undoubtedly saved lives. Brennan, a local theatre producer, connected us with hotels and secured hundreds of shower caps to be used as hair covers.

We were strangers in March, but have turned into a thriving albeit socially distanced family. It was precarious and turbulent aboard our rickety little relief ship at the beginning, but as the weeks have gone on and the pandemic has continued, we have found our sea legs. Our team continues to grow, made of people from all communities and walks of life, but largely composed of a queer core. We welcome people to continue joining our ranks, as this pandemic and the crises it has created are far from over. Whether here in NYC or anywhere across the nation, our website remains open to new volunteers and regional coordinators. We do not have chapters in every single state, and we would love for someone to step up in our underserved areas the way I did in NYC. Our donations continue to go wherever they are needed, but the ones we make to queer youth shelters and LGBTQ medical centers hold a special place in our hearts. We have connected with queer community organizations in every borough, and the ties that bind us together grow stronger by the day. Interacting with the medical system can be fraught for many queer people, and it can be rife with traumatic memories. But they continue to show up, and there is a particular nobility in those who fight to save a system that does not fight to save them.

As the racist murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade brought our country to a flashpoint, we have expanded to gathering masks and medical supplies for protestors and street medics, and I am heartened to see the queer community continue to show up again and again. From jail support to street medic bridge training to protest organizing, I see my kin everywhere, and I am proud. Black queer organizers have been at forefront of organizing and relief work for a long time, and I am proud to stand in solidarity with them now as always. The pain is palpable. The grief is unending. But there is and always has been strength in numbers, and ours continue to grow. People who I met for the first time on Instagram have reached out to make sure I’m doing ok. We end every conversation, every text thread, every Zoom meeting by saying “stay safe.” We know all too well that it is not safe, but we wish it for each other anyways.

Sometimes, I make eye contact with a stranger at a rally and there is an unspoken acknowledgement, I see you. Call it a spidey sense, call it an instinct honed over years of being unable to speak our realities, but Queer Eye Contact exists. And it is the most comforting thing. I see you. You are not alone. We will get through this. Together.

COMMUNITY CHECK is a series about mutual aid and taking care of each other in the time of coronavirus.

Support Black Community With Your Money: A Living Index of Local Mutual Aid Efforts

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual, which includes celebrating Pride. This week, Autostraddle is suspending our regular schedule to focus on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

- Jump to mutual aid funds by state.

- Contribute to this living document of mutual aid and community care.

This weekend, Carmen compiled a list of 70+ bail funds that you can donate to, and we still encourage that wholeheartedly. However, many major bail funds are asking for support to be redirected elsewhere, and many localized, on-the-ground efforts are in need of funding immediately so they can continue doing the vital work of community care. In any movement, the work of caring for community happens day to day at a hyper local level.

To that end, if you are looking to donate to vetted groups or individuals doing this work contributed by people in those same communities, we encourage you to use this list as a resource. And if you live in these communities and are looking for any variety of care – food, shelter, COVID-19 testing, or other organizing efforts – we hope these options will be a good starting place for you to find what you need. This post will serve as a living document, and will be updated as we receive more information. We hope it will grow to be much more robust, and we are grateful to everyone who helps it grow. If you know of efforts in your community that should be on this list, please fill out the form at the bottom of this post so we can include their information and others can send monetary support.

If you do not see your community on this list, have set up a regular donation to your local bail fund (which you can find either in Carmen’s post or by checking out National Bail Fund), and still want to give more money to support protests, the National Lawyers Guild has been protecting peoples’ and progressive movements’ right to protest and has been working in prison and police abolition for years. They have local chapters and can be found providing support to protesters across the country at this moment.

We’ll try our best to keep up with info as it comes in, although our staff and ability are necessarily limited. Please don’t share any information that could identify people organizing; we won’t be able to post it! If info here is incorrect or you need us to change or remove it, please email rachel@autostraddle.com and cc vanessa@autostraddle.com.

Know of a resource that should be on here and isn’t? Tell us about it here.

Navigate mutual aid funds by state:

- California

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia (DC)

- Florida

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- Nevada

- New York

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Wisconsin

California

Oakland

Black Earth Farms is a grassroots Black & Indigenous Agroecological farming collective. They’ve been giving food to protestors in the east Bay Area. Follow them on Instagram @blackearthfarms for frequent updates. Venmo @blackearthfarms or CashApp $blackearth to support their work.

Connecticut

New Haven

People’s Medics of New Haven (New Haven, CT): collective of healthcare workers and trained volunteers providing medical support (water, facemasks, hand sanitizer, etc.) to protestors. Donate with Venmo.

CTCORE-Organize Now! Mutual Aid Network: CT-wide organizing for reparations and liberation, organizer of COVID-19 mutual aid network.

Semilla Collective (New Haven, CT): New Haven-based mutual aid network focused on supporting undocu+ communities during COVID-19.

Citywide Youth Coalition (New Haven, CT): youth-led organization calling for divestment from police in New Haven public schools and reinvestment in counseling and mental health.

Justice for Jayson (Bridgeport, CT): youth-led abolition organization formed in the wake of the murder of Jayson Negrón by Bridgeport PD in 2017.

Radical Advocates for Cross-Cultural Education (Waterbury, CT): decarceration and antiracism organization focused on police abolition and dismantling the school to prison pipeline. More recently, they’ve been supporting BLM protests in Waterbury, where police have arrested 28 protestors & 2 legal observers.

Black Lives Matter New Haven (New Haven, CT): Black, significantly QTWOC-led local chapter engaged in decarceration, police abolition and antiracism activism & education. Second donation link here.

In addition to the CT Bail Fund and BLM New Haven FB accounts linked above, our local paper, the New Haven Independent, has done some decent reporting on local protests.

New Haven Pride Center: case management and food distribution during COVID-19.

Washington, DC

Ward 5 Mutual Aid: “DC is split into 8 wards, or giant neighborhoods. I live in Ward 5 and have been working with the Ward 5 Mutual Aid group to provide service navigation, limited cash assistance, groceries and masks to our neighbors. We’re a grassroots collective of all volunteers in the neighborhood. Each Ward has its own independent mutual aid “operation” and we work semi-independently of each other — if someone from another ward reaches out to us we will direct them to the appropriate ward for assistance. I don’t have info on the other 7 ward’s fundraising platform but I can’t say enough how amazing this group is. It’s been operating since mid-March and completed 900 some grocery requests. The city is so strapped that it sends people to these mutual aid groups when they need food and supplies.”

East of the River Mutual Aid Fund: “Black Lives Matter DC is raising funds for our Mutual Aid Network East of the River in Washington, DC. We are collecting and purchasing supplies to make hygiene bags, sack lunches, and provide other material support that we have started distributing. We are working to support as many of our neighbors who are housing and food insecure as well as others that need support East of the River in Wards 7 & 8 as possible.”

DC area restaurants supporting Black Lives Matter: A running list of restaurants and bars donating proceeds to Black Lives Matter DC and other racial justice organizations; planning events in support of BLM; or providing protestors with food and supplies.

DC lawyers and legal groups offering free legal help to protesters