Lesbian and Bisexual Women of History Who Were Obsessed with Their Dogs, Part 4

Parts 1, 2 and 3 of this series are not required but very enjoyable.

History, people say, has a habit of repeating itself. While that largely means we live at the mercy of the cycle of bad decisions made by a privileged few, it has one side benefit of providing a seemingly endless stream of queer women who were thoroughly besotted with their canine pets.

And so we find ourselves back for a barely conceivable fourth installment looking at the big dogs, little dogs and doggy dogs of yet more lesbian and bisexual women of history who were obsessed with them!

Margaret Wise Brown

Author of everyone’s fave secretly queer bedtime story, Goodnight Moon, Margaret Wise Brown was born in Brooklyn, New York City in 1910.

She spent her early years in a house overlooking the East River until, at her mother’s insistence, the family moved out to Long Island, so the kids could grow up in more natural surroundings. Margaret felt instantly at home in the outdoors, unleashing her adventurous spirit and wild curiosity. Importantly, the space also afforded the family a large house with ample room for many pets, including a squirrel, guinea pig and rabbits. Their family dog was a collie named Bruce, after the canine hero of the adventure dog stories by Albert Payson Terhune beloved by the Brown children. When she wasn’t roaming the countryside, Margaret was a voracious reader and story-teller, frequently adapting common tales with wicked twists to scare her younger sister, Roberta.

Margaret with Roberta, Bruce and assorted pets, courtesy Westerly Public Library

This love of books did not translate to academic success; Margaret spent far more time keeping up with her many sporting and social pursuits, first at boarding schools in Massachusetts and Switzerland, then as an undergraduate at Hollins University in Virginia. Despite students being banned from keeping pets at her Hollins dorm, Margaret decided she must have a canine companion. So she engineered a plan to buy a dog in town, then house it with one of the college staff to get around the rules.

Inspired by reading Gertrude Stein at college, Margaret harboured an overwhelming desire to be a writer, though she received less than encouraging feedback from her tutors for her creative writing. More pressingly, this didn’t fit the more practical career expectations of her father, who threatened to cut her allowance off if she didn’t get a proper job, or direct her education towards one. So, in 1935 Margaret signed up to teacher training at the experimental Bank Street School in New York. She was immediately tapped up by the head of the school to work on editing textbooks using their trademark “Here and Now” style, which focused on children’s experiences in the real world, rather than the fantasies and fairy tales that were common at the time. Margaret took to the style with gusto, and soon jumped from editing textbooks to writing them, and then story books of her own imagining, in a prolific career that saw her pen over 100 books over fourteen years. Aside from the sheer quantity of her output, Margaret was revolutionary in pushing new styles and formats that are commonplace now, including what was considered the first board-backed children’s book.

Where she had struggled to put together compelling adult fiction, she found no problem putting herself in a child’s place to conjure up stories that would appeal directly to them. In a guide book she wrote later in her career, Creative Writing for Very Young Children, she would link this ability with her animal kinship: “Children are keen as wild animals and also as timorous.” Despite her success, Margaret’s grasp on financial responsibility never really matured, spending whole pay-cheques on flowers, maintaining her lavish social lifestyle and buying up properties, then wondering how she couldn’t afford to pay rent.

While working at Bank Street, Margaret acquired her dog Smoke, an irascible Kerry Blue terrier that she took everywhere with her. At group editorial meetings, Smoke would curl and doze through readings, and when Margaret found things dull, a gentle toe poke to Smoke’s ribs would elicit a mournful howl to echo his mistress’s feelings. She was commonly seen flitting from publisher to publisher with Smoke under one arm, and a sheaf of manuscripts under the other.

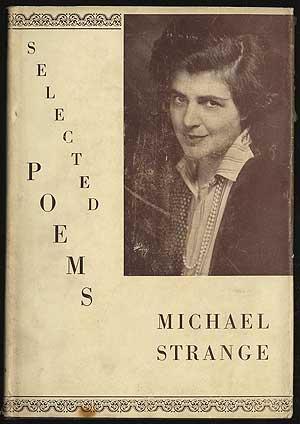

Margaret still spent a lot of time away from the city, enjoying country society from New England to Virginia and indulging in her passion for hunting with beagles. It was during a sojourn to the coast in the summer of 1940 that Margaret met the poet and actress Michael Strange, while they were both visiting a mutual ex, Bill Gaston. If that sentence didn’t provide enough foreshadowing, let me clarify that this gay-sounding meeting kicked off a decade-long tempestuous affair between the two women. Michael was known for her affair and marriage with famed actor John Barrymore (and the erotic poetry she wrote about it), which put her firmly among New York’s artistic elite. Margaret was dazzled by the confidence and sophistication of Michael, who was twenty years her senior. They moved in together in 1943, intent on creating the ideal artistic life, which slowly crumbled thanks to professional and personal jealousy, and the conflict between Margaret’s impulsive flightiness and Michael being a general bitchy drama queen. After a protracted illness, Michael died from leukemia in 1950, which devastated Margaret but ultimately freed her to continue with her life.

One good thing that came out of their relationship was Michael offering to get Margaret a new Kerry Blue after Smoke’s passing. At the kennels Margaret fell in love with the unruliest pupper of the bunch, which Michael tried and failed to protest against. Thus Margaret acquired Crispin’s Crispian (named after some dude in Henry IV)), who became even more infamous than his predecessor, thanks to a predilection for attacking trouser legs, upholstery and literally any other animal he encountered.

Margaret and Crispian

Crispian’s fame was cemented when Margaret inevitably made him the protagonist of his own book: Mister Dog: The Dog Who Belonged to Himself. The story sees Crispian living independently in his own house (modeled after Margaret’s own writing shed, Cobble Court), and his self-sufficiency so impresses a small boy that he chooses to join him in this lifestyle. I am sure this is meant to be making some kind of statement about kids learning independence but also seems a bit gay.

Crispian was just one of many dog and animal stars in Margaret’s phenomenal output. Other anthropomorphic canine characters include Muffin in The Noisy Book, who is temporarily blinded and thus begins to appreciate the sounds of the world. The illustrations for Muffin were based on Smoke’s pup Finnegan who, while modeling, peed on several of the drawings intended for the book. Further doggy pursuits are recorded in The Sailor Dog and Big Dog Little Dog.

To Margaret’s great dismay, the New York Public Library never stocked any of her books in her lifetime, but nevertheless she was loved across the globe. She began a French book tour in 1952, a precursor to a round the world trip she was planning with her new fiancé, a Rockefeller heir nicknamed Pebble. Of course, Margaret took Crispian along with her, despite the reservations of all her friends who knew what a cantankerous creature he was. Despite Margaret training Crispian to understand basic commands in French on the boat over, the wily pooch immediately got himself embroiled in a fight with a local dog, which inspired the following masterpiece:

The Crispian Blues

Bitten on the bottom

In my first fight in France

Why did I not

Wear a pair of pants?

Zut

Et crott

Zis

Ees

Not cricket.

Her trip was cut very short when she landed in hospital with a burst appendix. Although she survived the routine surgery, she developed an embolism while recovering and died. Without children of her own, Margaret’s legacy was split up in an unusual but highly sensible way, with half of her royalties going to whoever took care of Crispian. However, the only person that had read her will to know this was her manager Walter Varney, who immediately tried to wrangle ownership of Crispian to claim the inheritance for himself. This was quickly disputed by Margaret’s sister and literary executor Roberta, who eventually wrangled back control, but such was the nightmare of working with Margaret’s various publishers that over 70 manuscripts remained locked up in a trunk and unpublished until the 1990s.

In the 1970s, the New York Public Library finally decided they would start carrying Goodnight Moon, after two decades dismissing its modernist style, and even the need for a “go to sleep” kind of book. Its popularity rose from the thousands sold every year when it was published, to almost a million annually today, ensuring the legacy of Margaret Wise Brown is read around the world every night.

“I like dogs

Big dogs

Little dogs

Fat dogs

Doggy dogs

Old dogs

Puppy dogs

I like dogs

A dog that is barking over the hill

A dog that is dreaming very still

A dog that is running wherever he will

I like dogs.”

― Margaret Wise Brown, The Friendly Book

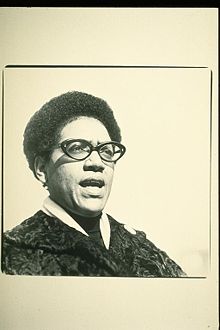

Billie Holiday

Iconic jazz singer Billie Holiday was born in Philadelphia in 1915, and raised in Baltimore. She suffered an unstable and abusive childhood, establishing a pattern that would define her personal life. Passed between relatives while her mother worked away and her father was nowhere to be seen, Holiday spent her early years surviving life and sexual assault in one of the city’s most impoverished neighbourhoods.

Billie moved to New York aged 14, where she was trafficked into the sex trade and later imprisoned for it. After release, Billie began singing in nightclubs, developing her trademark vocal style and phrasing, and started to gain some independence. However, the brutal realities of life as an entertainer and woman of colour in the segregation era saw Billie frequently at the mercy of unscrupulous men profiteering off her talent and burgeoning drink and drug addiction.

Thank goodness for dogs! In the absence of decent humans in her life, Billie was supported and comforted by a series of pet pooches throughout her career. As fellow singer Lena Horne recalled about Billie: “her animals were her only trusted friends” and an evergreen topic of conversation.

Among her menagerie were:

– Rajah Ravoy, named after a local magician, who she gave away to her mother

– Gypsy, a great Dane

– a wire-haired terrier named Bessie Mae Moocho

– a Standard Poodle who Billie, sobbing, wrapped in her finest mink coat for cremation when it died

– several Chihuahuas, including Moochy, Chiquita and Pepe, the latter whom she hand-fed with baby bottles and carried everywhere around town

It was Mister, an enormous Boxer dog, that became Billie’s closest companion, loyally sitting stage-side whenever she performed and generally happy so long as he could hear his mistress’s voice. In return, Billie knitted him sweaters, fed him steak and bought him his own mink coat (obviously there was a lot of mink to go around back then).

Billie’s drug use put her frequently at odds with law enforcement, not least because of the relentless campaign by Harry Anslinger, head of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics, whose personal vendetta against jazz culture, Black people in general and Billie in particular almost drove her to suicide. In 1947, police raided Billie’s apartment and busted her for possession, leading to a year in prison. After release, Mister (who Billie thought would have forgotten her), bounded up to her with such ferocity in the street that a bystander thought he was attacking her.

by William P Gottlieb

Prior to her incarceration, Billie’s commercial success had been at a high, with hit singles, record deals and a starring Hollywood film role. With her conviction somewhat restricting where she could perform, she still managed to play several sellout concerts in the late 40s, but the deterioration of her health from constant drink and drug abuse made performing increasingly difficult, and left her even more vulnerable to those out to exploit her. The shadows of Billie’s chaotic life managed to fall over even her most stalwart companion. Contemporaries recounted how in their drug-fuelled benders Billie and her friends hit and abused Mister, even shooting him up with heroin. Eventually, Billie gave Mister away to her pianist, Bobbie Tucker.

Holiday was arrested on drugs charges again in a Hollywood nightclub in 1948, San Francisco in 1949, and Philadelphia in 1956. When hauled off to City Hall for the latter charge, she insisted on bringing Pepe her Chihuahua with her, and he stayed the night in jail.

Billie managed to tell much of her own version of events in her 1956 autobiography Lady Sings the Blues, although notable omissions include her affairs with women, including Tallulah Bankhead, allegedly after Bankhead saw a draft manuscript mentioning their relationship and threatened to sue.

Holiday’s health worsened and by early 1959 she was seriously ill with cirrhosis of the liver, dying in July of that year. It’s said that in her hospital possessions were found a shopping list containing three items: cigarettes, gin and dog food.

Rosa Bonheur

I debated a long time about whether to include the 19th century artist Rosa Bonheur in this series. Sure, Rosa loved dogs, but she loved all animals, with no particular evidence she was more obsessed with dogs than others. I fretted: what if the pan-animal-loving community accused me of erasure? Conversely, what if the dog-lovers accused me of diluting their canine-exclusive identity?

Eventually I realised that loving a lion does not mean you love dogs any less, which I think is a valuable lesson for us all to learn. So, with gay abandon, let us celebrate the life and loves of France’s greatest cross-dressing animal painter, Rosa Bonheur!

Rosa was born into a family of artists in Bordeaux, on March 16th 1822. Naturally, she followed the family passion and was drawing from before she could read, or even talk, devoting hours to sketching her favourite subject: animals. Her obsession was so overwhelming that she eschewed learning to read and write in favour of drawing, until her mum ingeniously persuaded her to learn the alphabet by assigning her animal pictographs to draw, representing each letter.

Despite her quite obvious artistic desire and talent her dad was reticent to give her proper training for reasons that are not clear, so let us just blame the patriarchy. The family moved to Paris, and when Rosa’s insistence on becoming an artist wouldn’t abate (and she kept getting kicked out of school and apprenticeships for being unruly) her father finally relented. He began to bring back animals to the family studio for her to study, and she progressed to making field trips to the outskirts of Paris to paint livestock in their natural habitat.

It was while in Paris that Rosa began wearing trousers and other stereotypically “masculine” attire, largely for practical purposes. As a regular visitor to abattoirs as research for intricate anatomical studies, she discovered it was a real drag in skirts, but because it had been outlawed for women to wear trousers since 1800 (and not officially repealed until 2013!!), she had to obtain and constantly renew a permit to do so.

She had a house on Rue d’Assas where she somehow kept: “One horse, one he-goat, one otter, seven lapwings, two hoopoes, one monkey, one sheep, one donkey, two dogs, and my neighbour Mme. Foucault, mother of the famous physicist, who used to get on the wall to watch me mounting my mare, Margot” (not sure how Mme. Foucault feels about semi-inclusion in this list). As well as the animals, Rosa moved in her girlfriend, Nathalie Micas. Rosa and Nathalie had been at school together in Paris and matched each other with their passions for animals, with Nathalie frequently taking on the role of nurse to their unwieldy menagerie, and having a special talent for taming the various wild beasties they acquired. Nathalie’s mum also moved in with them, but as far as I can tell, she had no concern about her daughter’s lesbian affair. It is likely Mme. Micas was too distracted by the otter’s penchant for escaping its water tank and leaping into her bed. Even when Rosa attempted to give away animals, they had a habit of returning, as happened with a dog they gifted to a friend who immediately left and trotted the thirty mile trip back.

Rosa’s animal obsessions paid off, and after some early successes with huge pastoral scenes such as Ploughing in the Nivernais she was able to set up a much larger studio just outside Paris in Château de By, in 1859. She immediately set about moving in an even more outrageous array of pets, including but not limited to:

– stables filled with all sorts of horses, ponies and cattle

– dogs roaming all over the place, including collies, enormous St Bernards’, hunting hounds, dachshunds and terriers

– stags, wild sheep and gazelles

– a parrot called Green Cocotte who could swear in Spanish

– a monkey called Ratata

– a pair of lions named Nero and Fathma.

Naturally, many of these animals were the subjects of the many hundreds of artworks she produced over her lengthy career, including dozens of dog portraits and studies.

Of all the dog obsessives I have studied, Rosa is perhaps the first that has made me wonder if she was actually an addict, frequently documenting her inability to go anywhere without acquiring a new pet. Witness this time she went on a trip in the Alps in 1850 and got a giant mountain dog:

“My dog is getting enormous. I don’t know how I shall manage to convey him from here, for he will be as big as a donkey, Dear me! What an unfortunate hobby mine is! What would you say if I were to confess what efforts I have made to resist the desire to bring back a sheep and a goat? I really can’t help it.”

Among her named dogs, we have: Belotte, a large yellow bassett, Pastour, Ulm (a big Danish dog), Niniche (a Corsican mouflon), a Scottish terrier called Wasp, a beagle called Ramoneau, long-haired Daisy and Charlie, who Rosa trained to do tricks, and her favourite, Gamine, who was glued to Rosa’s side, lording it over the other animals and always the first to scraps at the dinner table.

After almost 40 years together, Nathalie passed away, in 1889. A few years later, the couple’s friend Francis Power Cobb lost her own partner Marie Lloyd, and Francis and Rosa exchanged letters and photos of their loved ones with their faithful dogs, to remind them of their happiest times.

Rosa was not alone for long. An American painter named Anna Klumpke met Rosa on one of her regular trips to Paris, and the two hit it off. Anna had idolised Rosa for years, and even had an official androgynous dress-up Rosa Bonheur Doll. Anna plucked up the courage to ask if she could paint Rosa’s portrait on her next visit, to which Rosa agreed and they promptly fell in love during the process, because all clichés have to start somewhere.

Rosa with Charlie by Anna Klumpke

Anna moved in to the chateau and they lived together until Rosa’s death in 1899. Anna maintained the estate (including all those animals) until her own death in 1942. Rosa, Nathalie and Anna are buried together in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

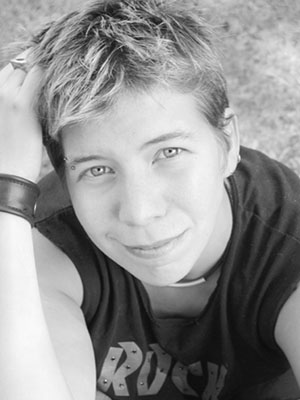

Edith Somerville and Violet Martin

Both daughters of wealthy 19th century Irish gentry, Edith Somerville and Violet Martin met in 1886 in Castletownshend, the small village near Edith’s family residence, Drishane House. I suppose tangentially it was Violet’s family home too, as the pair were second cousins, although they didn’t encounter each other until their mid-twenties so probably it was totally fine that they embarked upon a lifelong artistic and romantic relationship together.

Eldest of eight siblings, Edith was a smart and confident character, with a passion for reading and drawing, and a determination to make her own way in the world. After persuading her parents to let her go abroad to study art, she was able to earn a living as an illustrator and set herself up with a studio on the family estate. With no desire for marriage herself, Edith was devastated when her childhood “best friend” Ethel tied the knot, and was entirely unattached when she met Violet.

Similarly self-motivated, Violet was a self-taught linguist and keen student of the written word, and was trying to get some of her articles published when a family member suggested she seek out Edith to provide illustrations. Their collaboration was an instant success, and the pair clamoured to spend more time together despite familial obligations and financial dependency keeping them apart.

I suppose our respective stars then collided and struck sympathetic sparks. We very soon discovered in one another a comfortable agreement of outlook in matters artistic and literary, and those colliding stars lit for us a fire that has not faded yet.

– Edith Somerville describing casually meeting her cousin Violet.

Violet helped redirect Edith’s passions in a more literary direction. Their first novel together was, ironically, An Irish Cousin, and after positive reaction to the book, their families were somewhat content to let them continue their unusual collaborations. For the first two decades of their partnership, they didn’t live together, but would meet for intense periods of “creativity” and constantly mailed manuscripts and letters to each other. They continued to have success, publishing a number of novels satirising Irish country life, using the joint pseudonym “Martin Ross.”

After the death of Edith’s parents and Violet’s mother, there were few remaining obstacles in the way of the pair moving in together, and they spent the last nine years of their relationship in Drishane house. As the head of the household, Edith assumed responsibility for running the estate, including taking over the hunting hounds, becoming Ireland’s first female Master of the Foxhounds. While they loved the hounds for the hunt, Edith and Violet were also fans of fox terriers, and liked to trot around with them in threes, leashed up like a Russian troika.

Edith and Violet with two of their fave fox terriers, Candy and Sheila

Violet died in 1915, after a long illness following a horseriding accident. However, Edith casually resumed her relationship with Violet on the astral plane, which is as you’d expect for a queer woman. Not only did Edith claim that Violet contacted her from beyond the grave, she also brought with her news of their long-dead pet dogs. For the rest of her life, Edith continued to use the pen-name Martin Ross, as she fully believed she was still writing in conjunction with her deceased lover. Although Edith went on to live for a further three decades, she remained faithful to Violet’s spirit, despite attempted flirtations from fellow suffragist and dog enthusiast, Ethel Smyth.

Edith’s (and ghost-Violet’s) final work was Maria and Some Other Dogs, a selection of previously-penned doggy stories and new musings on the canine condition, collected with illustrations. As well as obligatory tales from a dog’s-eye view, there is a chapter titled “In Praise of Ladies” which although allegedly pertaining to female dogs, could easily be read as a treatise on why females of any species are better.

Yet I am well aware that I am not alone in valuing the Lady, as an intimate, above the Gentleman of the race. I have seldom met an Initiate in the cult of the Dog who did not confess to a preference for the popularly unpopular lady.

Further gems in the collection include the story of a dog whose extreme naughtiness prompted a name change from “Cozy” because that sounded too placid, and a recollection of impressing Thomas Hardy’s widow with accounts of psychic pooches. There’s also mention of private stories about one of their dogs, Puppet, that Violet wrote for Edith, but the latter declared “too esoteric” to print, which is really saying something.

Edith completed the manuscript mere days before her death in October 1949, ensuring a mortal account of her canine obsession was left behind before she rejoined Violet.

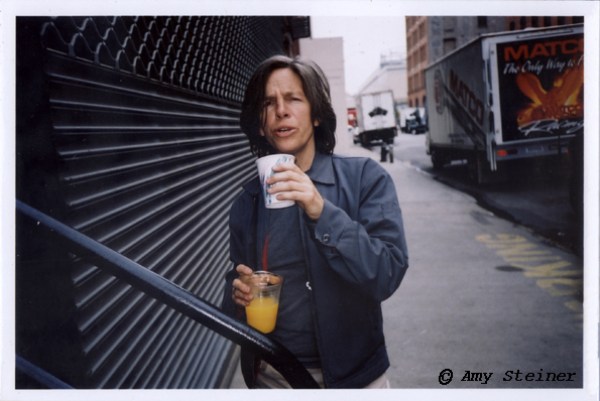

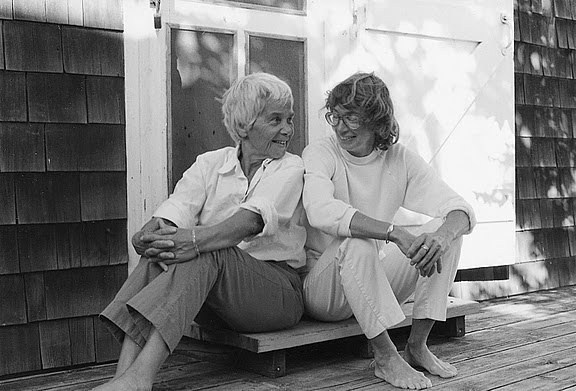

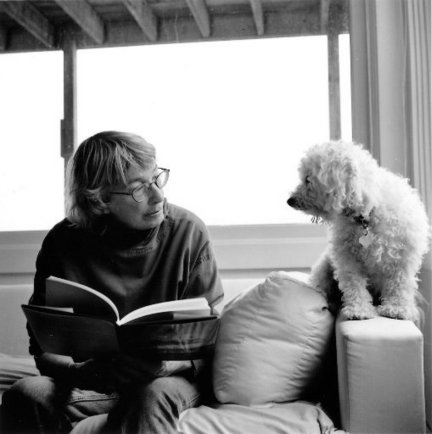

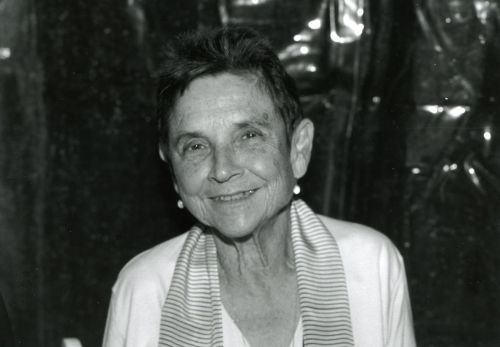

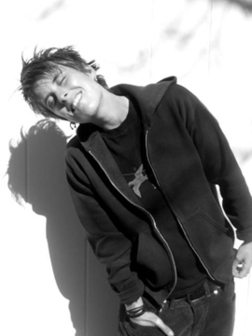

Mary Oliver

Beloved American poet Mary Oliver sadly became an official lesbian “of history” when

she died in January this year, aged 83. Throughout her long and successful career, Oliver’s work focused on the natural world, walking daily in the forests and beaches of Provincetown, where she lived a private and simple life.

Oliver studied at Ohio State University and Vassar, developing her passion for poetry. It was one such passion for the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay that took her off to Millay’s home in the tiny town of Austerlitz in upstate New York. It was there in the late 1950s that she met (presumably the only other gay in the village) photographer Molly Malone Cook, who would go on to become Mary’s literary agent and partner of more than 40 years.

While she lived with Molly until her death in 2005, Mary also had constant canine companionship throughout her life. References to her beloved dogs are littered throughout her many volumes of poetry and prose, so many that they got their own collection: 2013’s Dog Songs.

Each poem is a gem, capturing the small delights of human-canine interactions, from silent conversations with her dogs watching the moonrise, to cancelling work trips at their mournful howls, to playful interruptions to her tax returns. It is hard to pick out any single one, but here is Mary herself reading Little Dog’s Rhapsody in the Night:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioTvAtNk5kg

In fitting with her beliefs on nature and wildness, Mary fervently believed that dogs should be free to roam off leash in their surroundings. Otherwise, a dog is a mere “ornament of human life.” But, unleashed: “Dog is one of the messengers of that rich and still magical first world. The dog would remind us of the pleasures of the body with its graceful physicality, and the acuity and rapture of the senses, and the beauty of forest and ocean and rain and our own breath.”

Mary also had the rare foresight to use her essay Dog Talk to list in one place every single dog she had owned (FYI I’d really recommend doing this if you ever plan on becoming a lesbian/bisexual woman of history who is obsessed with your dogs because it will make your chronicler’s life so much easier):

“Baba, Chico, Obediah, Phoebe, Abigail, Emily, Emma, Josie, Pushpa, Chester, Zara, Lucky, Benjamin, Bear, Henry, Atisha, Ollie, Beulah, Gussie, Cody, Angelina, Lightning, Holly, Suki, Buster, Bazougey, Tyler, Milo, Magic, Taffy, Buffy, Thumper, Katie, Petey, Bennie, Edie, Max, Luke, Jessie, Keesha, Jasper, Brick, Briar Rose.”

Through the poems of Dog Songs we get to learn the wild and cantankerous personalities of many of these pooches, and of their owner.

“Be prepared. A dog is adorable and noble.

A dog is a true and loving friend. A dog

is also a hedonist.”

Mary Oliver, The Wicked Smile

Oliver’s essay Winter Hours offers some of the most accessible insights into her feelings about nature (and even a little bit about her relationship with Molly). In it, she describes how after her dog Luke died, she would retrace her steps through the woods where they had walked together, covering the remains of Luke’s pawprints with bark and leaves, so she might preserve them. While a violent rainstorm finally washed those pawprints away, the vitality of life and nature that Mary Oliver captures in her poetry will leave a legacy for generations.

Because of the dog’s joyfulness, our own is increased. It is no small gift. It is not the least reason why we should honor as love the dog of our own life, and the dog down the street, and all the dogs not yet born. What would the world be like without music or rivers or the green and tender grass? What would this world be like without dogs?

Mary Oliver, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Lesbian Poet, Is Dead at 83

Mary Oliver, Pulitzer Prize-Winning poet and ardent devotee of the natural world throughout her life, has passed away from lymphoma at the age of 83.

Oliver’s first book of poetry, No Voyage and Other Poems, was published when she was 28; she won the Pulitzer for her fifth, American Primitive. Her favorite subject was nature and the various complicated lessons found there; the AP notes that “One of her favorite adjectives was “perfect,” and rarely did she apply it to people.” Her writing practice involved long walks in the woods, which she described as “successful” when they ended in her stopping to write — she hid pencils in the trees of the local woods so she would never be caught without one while hiking. In a rare interview — Oliver was notoriously reserved about her personal life — with Maria Shriver, she shared that she had survived sexual abuse in childhood, an experience that she described as leaving her wanting “to be invisible,” and which she became more open to exploring in her work later in life.

Oliver met Molly Malone Cook, a photographer, in the 1950s; the two were partners for more than forty years, making a life together in the longtime gay haven of Provincetown, MA where Cook worked as Oliver’s literary agent. Cook passed away in 2005; asked how she dealt with her partner’s death, Oliver answered simply, “I was very, very lonely.”

Even when Molly got ill, I knew what to do. They wanted to take her off to a nursing home, and I said, “Absolutely not.” I took her home. That kind of thing is not easy… I had decided I would do one of two things when she died. I would buy a little cabin in the woods, and go inside with all my books and shut the door. Or I would unlock all the doors—we had always kept them locked; Molly liked that sense of safety—and see who I could meet in the world. And that’s what I did. I haven’t locked the door for five years. I have wonderful new friends. And I have more time to be by myself. It was a very steadfast, loving relationship, but often there is a dominant partner, and I was very quiet for 40 years, just happy doing my work. I’m different now.

Oliver’s most famous and widely shared poem, “Wild Geese,” combines the themes that in many ways defined her life as a staunch advocate of the natural wild and a survivor: allowing oneself forgiveness and softness, weaning oneself off of self-recrimination, finding solace and perspective in the rhythms of the natural world. Perhaps her most oft-quoted line is from “The Summer Day” — Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?”. Asked in 2011 what she had done with her one wild and precious life, Oliver said “I used up a lot of pencils.”

Mary Oliver was a hugely influential and urgently necessary poet to many, including countless readers to whom poetry as an institution was often inaccessible or opaque; her words provided comfort, joy and respite to generations. It’s hard to know what to say to appropriately honor her life; luckily, Mary Oliver has already done the work of providing some thoughts on her passing in her poem “When Death Comes.”

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps the purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle-pox

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth,

tending, as all music does, toward silence,

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.

When it’s over, I want to say all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world

The 8 Most Asked You Need Help Questions, Answered

We spend a lot of time giving advice here on Autostraddle dot com. All of our writers give it in our You Need Help column. Laneia gave it three-at-a-time (sometimes more!) in her Y’all Need Help column. We were giving so much advice in our A+ Some Answers to Some Things You’ve Been Asking Us column that we had to make it into its own A+ Advice Box column. We even have a dedicated advice video series by Kristin Russo that that airs on our Facebook live and is then published on our website.

It makes sense that people ask us so many questions, of course: we’re the only dedicated queer website giving advice written by queer people to queer people about queer-specific topics. What’s interesting and also heartbreaking about the questions people send in most is that they’re obviously feeling a real sense of isolation when they write to us; yet the questions they’re asking are often being asked by so many other readers. So, I thought, “Hey, why not compile a list of the eight most asked You Need Help questions, so people can feel less alone in their worries and also because it will be a great resource!” And this is that!

How do I deal with internalized homophobia?

Internalized homophobia is the great equalizer in the LGBTQ community. It strikes across demographics with impunity. Age, gender, race, nationality, socioeconomic status, religious upbringing, mental health, physical health — there’s no barrier it doesn’t cross. And heavens to mergatroid, how it manifests itself! The way we feel about how we dress, how we choose to label ourselves, the masks we wear in various social settings, it even follows us to bed and informs what we do and don’t do in our sex lives. Internalized homophobia is a relentless motherfucker, and just when you think you’ve conquered it, it pops its little head up like an evil game of whack-a-mole in the place you were least expecting.

Which is probably why internalized homophobia is the thing people ask us about the most. Is this internalized homophobia? (Yes, probably.) Is that internalized homophobia. (Yes, probably that too.) One of our most commented on A+ posts last year was a roundtable in which our staff talked about what internalized homophobia looks like to them. Some of us have been working as professional gays for over a decade and internalized homophobia still shows up in our brains and hearts and actions.

So how do you deal with it? Well, first you identify it. Internalized homophobia a kind of self-hatred of certain parts of yourself that comes from homophobic things you’ve heard other people say, or tropes you’ve seen on TV or in movies, or beliefs held by your religious or political institutions, or even just general culturally murmurings. Once you’ve pegged something as internalized homophobia, you can start unpacking it: Who said the homophobic thing that, to this day, makes you dislike a part of yourself? Why did that person saying it affect you so profoundly? Does their opinion matter, all these years later, more than your own health and happiness (no!).

Once you’ve held that internalized homophobia up to the light and examined it, you hurl it into the sun and keep living your life.

If it helps to know someone’s livid on your behalf, Laneia is here: “Whatever other people think about you is on them. It reveals who they are, not you — it has nothing to even do with you! And yet you’ve been doing all the contorting and making all the adjustments in an effort to prevent them from possibly having a reaction. FUCK THAT. I am furious on your behalf. Be who you are, and be loud about it. Take up the fucking space.”

I’m in love with my best friend. Help!

Three years ago, when there were only about 15 total queer women on TV, Riese was still able to make a list of Lesbian Falls For Her Best Friend storylines. It’s a tale older than time itself. It’s what we, as a people, do. Your foremothers did it and in a hundred years the gays out here continuing to watch The L Word for some reason will do it. We were born into this world falling in love with our best friends and we will exit this mortal plane doing the same. That’s the first thing you need to know: You are not alone!

Friendships between women are often really intimate situations, so when you’re inclined to smooch the same people you share your deepest, darkest secrets and most true and whole self with, things get complicated. Ask yourself these questions:

+ Is your friend queer, too? (If not, skip ahead to the next question.)

+ Is your friend single? (If they’re in a relationship, nope right out of that confession you’re thinking about making.)

+ Are you ready to do the work to not make it weird if they’re not interested? Oftentimes, when we confess our crushes, if they’re not reciprocated, our friend just wants things to go back to normal, but we’re the ones who make it awkward because the rejection does a number on us. Can you be chill if she says no?

+ If it’s a yes on all three of those things, go for it! You get one life on this planet and you’ve made a connection with someone and now you want to deepen it. Avoid elaborate promposal-style confessions and expensive love notes written in the sky. Save that for your anniversary. Tell them; make sure they know that if they’re not feeling it, your friendship is still a-okay; take the next step based on whatever they say. Because this is a tale as old as time, there’s probably no way you’re going to escape being in this situation at least once, and there’s probably no way your friend is going to escape it either.

How do I deal with this crush on this straight girl?

Friend, you must trust me when I say: Stop, immediately! Get off the train tracks! For every one queer person who ends up happy with a formerly “straight” girl, there are nine hundred and fifty-eleven bazillion-quadrillion queer people who get their hearts shredded by falling in love and chasing after straight girls! You deserve more than this crush on a person who will not and honestly cannot reciprocate your feelings and desires!

Laneia once dedicated an entire Y’all Need Help column to this eternal lesbian quandary, and in it you will find all the firm but gentle truth you need on this subject:

I’m truly honestly sorry to say that you’ll have to bleed this out for a while. It’s been six months and where has this pining gotten you? NOWHERE, FRIEND. The energy you’re putting into this situation is the same energy you could be putting into literally anything else, and the energy you’re receiving from this situation is tepid and ultimately destructive. Straight women who’ll never date their queer friends that have crushes on them still manage to receive the positive energy of a queer relationship without having to reciprocate any of it. Think about that. You’re giving her your dating/loving energy and she’s giving you pal energy, and she loves it — not because she’s a selfish asshole, but because that energy is GLORIOUS and AMAZING and she’s probably never received anything like it before… This is not the person for you. She is not for you. She is your friend.

Laneia is so for real about this very correct advice, and so committed to making sure that you follow it and find the inner strength to look out for number one (that’s you), that she’s crafted a newsletter you can receive every single week to remind you that you deserve more, better, an actual real shot at a relationship with an actual real queer person. You can (and should) sign up for it right here.

Is she The One/The One who got away?

So many people ask so many variations of this questions. In fact, it was one of the biggest questions people had about sex and relationships in our Ultimate Lesbian Sex Survey.

The good news, sweet friend, is that there’s no way The One got away because there’s no such thing as The One. Which also means you’re off the hook on trying to figure out if she’s The One because that’s an imaginary thing made up by greeting card companies and ad agencies and Hollywood. I have written about this extensively, so forgive me, but I’m just going to quote myself:

So many movies and books and TV shows and commercials and songs and poems tell the tale that there’s one single person in the world who’s gonna fill up our hearts with joy and when we find them — snap! — life’s a breeze. There’s a kind of comfort in that, maybe, but it’s just not true. Every day we make a zillion small choices that change the shape of ourselves and the course of our lives in a zillion small ways, and every other person is out here doing the same thing. How cruel that the universe or some deity contained within it would make a single match for us, give us both free will, and then sit back in apathy while we go about our lives hoping to make the one correct series of choices that will allow us to brush up against one exact person who has also made one correct series of choices, in a sea of seven billion people making eleventy kazillion choices. The odds that anyone would find their One are nearly impossible!

And believing in The One can actually do way more harm than good to us and to our relationships. It can cause existential crises when things inevitably get hard with our person: “Well, maybe they’re not The One. If they were The One, this would be much easier.” It can make us call our relationships into question if we have a connection with a different person than our person: “There’s no way I could have a feeling for someone else if my current person was The One. Maybe the person giving me the new feeling is The One.” It can cause us to believe there’s one single person in the world who can (and should) meet all of our sexual, social, emotional, intellectual, and pragmatic needs — and without conflict or compromise. It can cause us to believe that being happy together just happens. After all, we were made for each other.

The truth, actually, is that there are a zillion things that factor into longterm compatibility and the success two people will have when they commit themselves to each other for a lifetime. Feelings about money, feelings about sex, feelings about religion, feelings about kids, feelings about careers, feelings about downtime and feelings about bedtime, sense of humor, schedules, the ability to communicate, the ability to sacrifice, the ability to grow, the ability to let someone else grow, the way you argue, the way you heal, the willingness of both people to work, work, work.

Yes! It’s scary as heck to commit yourself to another person with all those variables (and more!) in play when it comes to having a healthy, successful relationship — but isn’t it way more daunting to imagine your one shot at happiness in life comes from finding the one person (out of seven billion people!!!!!) the universe created for you?

How do I make queer friends?

We get almost as many questions about how to make friends as we do about how to make relationships work. That’s because making friends as an adult is hard, and even more so if you’re queer. When you’re in school, you drift toward people with similar interests who show up in the same place at the same time as you every single weekday for years and years. You have the same tasks to complete, the same authority figures to bemoan, the same sports teams to rally around, the same academic goalposts to reach in the same timeframe. When you’re a grown-up, unless you belong to a church or a club, the people with built-in proximity to you are usually your co-workers, most of whom are probably straight and many of whom are partnered up with a person they spend most of their time with.

How do you find the gays who like to do the things you also like to do. You can take two approaches: You can either hang out in group settings doing the things you like to do (pottery classes, cooking seminars, gaming groups, athletic clubs) and keep your eyes open for other queers; or, you can go to queer spaces and find people within those spaces who enjoy similar things as you. Those spaces can be real-life meet-ups, retreats, or things like comic-cons. Or they can be queer websites, social media, or even dating apps. (Almost all of my real-life friends are people I met online at first!)

It takes real courage and vulnerability to try to make a connection with another human being on this planet, but the good news, according to our inbox, is that you’re not wandering around out in the desert alone: Other queer people are out here looking for you too! (See: here and here and here, for just a little bit of proof.)

What if I’m bad at this or that sex thing/sex in general/want to do this sex thing/don’t want to do that sex thing?

The majority of questions we get about sex are really just people seeking reassurance that they’re normal. Are they having sex the same amount as other people, the same way as other people, the same duration as other people? Are they doing it too much? Not enough? Have they waited too long to get started? Is what they want weird? Is what they don’t want weird? What’s the right way to orgasm, what’s the correct amount of orgasms, what’s the correct number of people for orgasms, what’s the correct toys for orgasms?

Friend, what you want is okay! Our desires and our sex lives are so layered and varied and complicated and deeply personal, so informed by our unique life experiences and societal pressures and cultural norms and religious upbringings, so tied together with the way we feel about our bodies and inside our bodies on any given day, so very constantly evolving. There’s no normal. There’s just you and what you want (for whatever reasons!) and another person or people and what they want (for whatever reasons!) and a chance to pursue those wants (if you want).

Here’s Kaelyn: You Need Help: You Want to Have Sex But Also Sex Is a Lot Wow So Complicated

And Carolyn: You Need Help: Getting Out of Your Head and Into Her Pants

And Carrie: You Need Help: You Can Want Sex Exactly as Much as You Want (or Don’t)

And Christina: You Need Help: Even Sex Gods Get Anxious Sometimes

And here is an entire archive of Lesbian Sex 101 posts, with advice about everything from sex toys to thirst traps to play parties to positions to cruising to accessibility to polyamory to tops to bottoms to switches to scissoring.

I’m worried I’m too old for [thing]!

Oh my gosh the number of 19-year-olds who are worried that they’re never going to have sex and the number of 23-year-olds who are worried that they’re never going to find true love and the number of 30-year-olds who are worried that they haven’t yet published a best-selling novel and the number of 35-year-olds who “still” aren’t sure what they want to do with their lives. I just want to wrap you all up in a consensual Hufflepuff hug (Huffle-hug) and whisper into your ear that time is an illusion, and you are never too old to do the thing you want to do.

I’ve written a lot about how queer time moves differently than regular time, and about how we’re on our own schedule, outside the rigidity of the patriarchal space-time continuum. And it’s as true as it ever was.

It often takes us longer to figure out what we want than it takes our straight cis peers: “Because our community struggles with higher rates of depression than the general population; because we haven’t historically had role models in books and TV shows and movies to show us the way; because political parties and religions have consistently scapegoated us and tried to take away our civil rights by distorting or erasing our stories; because we didn’t have a chance to test out our futures playing make-believe as kids or a chance to talk out our futures with our parents or pals or guidance counselors, for fear of seeming weird or because we didn’t even know queer adulthood could exist.”

So some of us get a late start, and some of us have to completely start over. And both of those things are okay! You don’t have to prove anything to anybody! You’ve heard the stories about the 80-year-old woman training for a running a marathon, the 75-year-old women who fell in love, the 72-year-old woman who published her first book, the 91-year-old woman who graduated from college. All the moments you’re alive on this earth, every single one of them right up to the very end, you get to choose whether or not to inhabit them fully. Live, friend! Live all the way through!

I want to do this thing, but what if when I do this thing that thing happens and then that leads to this other thing, or what if I do it and this scary thing happens, or what if I do it and this embarrassing thing happens, or what if doing it leads to some kind of butterfly effect where I end up alone and ashamed forever?

Dearest, there are two ways to live your life: You can either be the one making the million decisions every day that affect your health and happiness, or you can sit still and let someone else make those decisions for you. Either way, you’re deciding something. Inaction is as much of a choice as action is. You cannot know every outcome (and that outcome’s outcome and that outcome-outcome’s outcome). There’s not usually a right or wrong way forward. The only thing you can do — the only thing any of us can do — is consciously make the next decision about our next step with the information available to us at the given moment, and then the next, and the next, and the next.

I wrote a three-week series earlier this year about figuring out what it is you really want and going after it with clear eyes and a full heart. You probably will be scared, and you actuallt might end up embarrassed, but those are only temporary emotions and a small price to pay for not allowing your entire life to be a series of guest-starring roles in other people’s movies.

I will end, as I almost always do, with Mary Oliver. This one’s “The Journey.”

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice—

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do—

determined to save

the only life you could save.

You Need Help: What Should You Do With Your One Wild and Precious Life?

Q:

How am I supposed to move on and like build a life or whatever when I never really thought I would? I spent so long dealing with a variety of mental health shit, but now that I’m mostly better I have absolutely no idea where i’m supposed to go from here. like, you mean I’m not supposed to throw all my energy into self destructing and burning down everything that could be good at every minor inconvenience?? can’t relate. i’m in my mid twenties and i’ve never been in a real relationship with anyone, let alone a girl, and i have no idea what i’m doing or even what i even want, in large part because i never envisioned a future where i wasn’t actively self-sabotaging. i know it’s ridiculous, and i’m glad i’m not in that place anymore, but at least i had a sense of mission then. now i just have…the rest of my life? and no idea how to approach that?

A:

This is a series of great questions, friend. The fact that you’re able to ask these things — the fact that you’re able to say, “I dove into my mental health stuff, pinpointing and addressing the reasons I’ve been self-sabotaging” — is a rare and wonderful gift you’ve given yourself. Most people never do that hard and painful work, so take a minute to appreciate the fact that you did. You deserve to stand still and enjoy some deep breaths and be proud of yourself. Usually humans figure out what they want to do and then find themselves in a crisis about who they are. You’ve done it the opposite way, and I think you’re going to discover what a good decision that was.

These questions are also great because a lot of queer people feel this thing you’re describing, this sense of being unmoored or aimless or overwhelmed with the prospect of living adult lives we — unlike our cis, straight peers — never imagined. Because our community struggles with higher rates of depression than the general population; because we haven’t historically had role models in books and TV shows and movies to show us the way; because political parties and religions have consistently scapegoated us and tried to take away our civil rights by distorting or erasing our stories; because we didn’t have a chance to test out our futures playing make-believe as kids or a chance to talk out our futures with our parents or pals or guidance counselors, for fear of seeming weird or because we didn’t even know queer adulthood could exist.

What you’re feeling is perfectly normal, is what I’m saying.

Now your choices are seemingly infinite and you don’t know what to do. That’s normal, too! Have you ever watched Top Chef (or any cooking show)? Give ’em a challenge like “Make a dessert with this lemon, bok choy, blue cheese, and shoelaces,” or “Craft a soup based on an Emily Dickinson poem” and in 30 minutes they put together a dish that has the judges in raptures. But turn these world class chefs loose in the kitchen and tell them to cook anything they want, and they go berserk. They bake inedible Rösti and then cry into the camera about how they’ve never even eaten a potato, or they try using liquid nitrogen to cook spaghetti, or they forget to turn on the oven. There’s science behind that. Psychologists call it “overchoice” and it means the more options we have available to us the more stressed out we get because we’re incapable of processing all the potential risks and outcomes from an endless cacophony of possibilities. The anxiety caused by overchoice is even more debilitating when we perceive a time limit on our decisions. (Really, I one time saw a James Beard Award-winning chef serve Padma Lakshmi a raw egg cracked into a bowl.)

I sense from your question, in which you mention your age as a barrier to planning your future, that you’re feeling that time crunch. I have good news: You’re doing that to yourself! There’s actually no cosmic clock counting down the time you have left to meet a girl, fall in love, and commit your lives to each other. The minutes aren’t melting away for you to choose a career or a college or a city to live in. That’s some straight people nonsense. You’re only in your mid-20s and you’ve already discovered the major source of your internal strife and you’re already dealing with it. You’re actually way ahead of the game. So tell that tick-tocking in the back of your mind to cut it out; it’s an imaginary sound.

Now. The fact that you’ve already done so much work on yourself probably means you know a lot about who you are and what brings you joy and what makes you feel miserable inside. Using those parameters you can start narrowing down your choices. If you know you don’t like root vegetables, don’t make gingered carrots to serve to the judges, for example. Do you need lots of sunshine and nature to feel sustained in your soul? Well, you’re not moving to London. Do you need to be surrounded by people in an office all day to feel sane? Well, you’re not becoming a freelance artist. What do you like to do? What do you not like to do? What are you good at? What do you want to be better at? What makes you happy? Really, truly, incandescently happy? The truth is, the world is not your oyster. The possibilities in front of you aren’t endless. And that’s a good thing! You just need to tell yourself the things you already know and then take one step toward those things, and then one more step, and then another. You don’t have to sit down in front of your Passion Planner today and mind-map a plan to orbit Saturn. If you want to orbit Saturn, take one step toward getting better at math and science.

And the same goes for dating. One step at a time. Figure out how you want to meet girls, figure out the kind of girls you want to meet. Maybe apps are a good choice for you: casual encounters without much emotional labor. Or maybe you’d rather look for someone in-person, say at an Autostraddle meet-up or a political rally or an event at a bookstore. Or something in between. Maybe you want to seek out an online space where people are enjoying each other’s company around a TV show or hobby or activism, and then just take it from there. Talking to people is so much easier when you already have a shared interest or core value in common. Yes, there are endless ways to meet girls in the world, but you know you and you know which of those ways best fits your life.

Sometimes it helps to hear another person’s story and so I will tell you mine: A couple of weeks ago I was walking downstairs and stopped short. My partner was sitting there, cute as kittens in her winter pajamas, playing a video game on the PlayStation we bought each other two Christmases ago, in a gorgeous vintage armchair we picked out together, in the living room of the beautiful new house we just moved into. Cat on the couch, cinnamon rolls in the oven. I was taking a break from my dream job here at Autostraddle to eat a late breakfast. The reason I stopped short is it took me by surprise, the realization that I never planned for any of this. I didn’t figure out I was gay until my mid-20s, didn’t have my first real girlfriend until later than that, and didn’t publish my first piece of writing — a blog post about The Golden Girls I wrote for an entire seventeen dollars — until I was 29. By the time I came out I thought it was too late for me, that the chance to have anything I actually really wanted had passed me by, that the world had moved on without me while I was crunching numbers in a cubicle and trying to disentangle myself from a confusing and toxic relationship. I was so wrong. Queer time moves differently than regular time; we’re on our own schedule; we exist outside the rigidity of the patriarchal space-time continuum. I just kept taking the smallest steps toward what I wanted and ten years later I’m exactly where I want to be with the person I’ll spend the rest of my life with.

Questions like these always call for Mary Oliver, and for you (like for me) I think it should be “Wild Geese.”

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about your despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

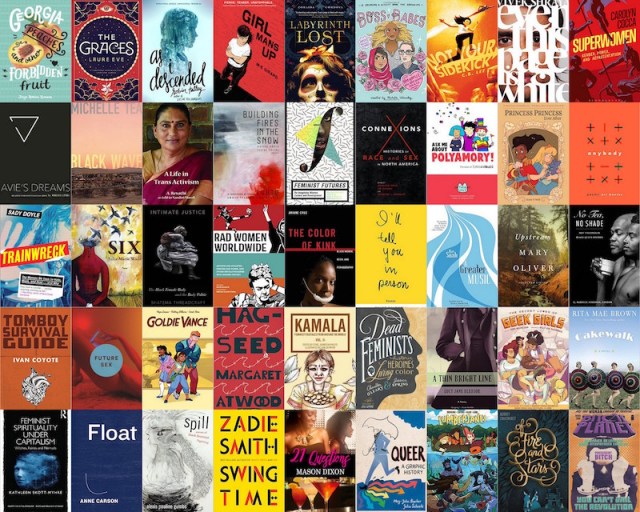

Fall 2016 Book Preview: 48 Queer and Feminist Books To Add To Your Reading List

Fall 2016 is looking great for queer and feminist reading! With new work by heavy hitters like Zadie Smith, Ivan Coyote, Anne Carson, Margaret Atwood and Michelle Tea; newly translated work by Bae Suah; poetry collections; explorations of the intersections of race, gender and sexuality; light-hearted romance; queer comics; gay YA; memoirs in metaforms and more, your reading list is about to explode. You’re welcome.

Georgia Peaches and Other Forbidden Fruit by Jaye Robin Brown

When Jo’s radio evangelist dad remarries and moves their family to conservative Rome, Georgia, he asks her to slide back into the closet for her senior year of high school — and, with the promise of her own teen radio show for discussing religion and queerness, she agrees. When she falls in love with a Christian lesbian who’s over the closet, things start to get complicated. (30 August)

The Graces by Laure Eve

The Graces are a glamorous family of teen witches who’ve cast a spell over their high school, their town and maybe the world. River, the new girl in town, desperately wants to be part of their family, for reasons that become clear even through layers of deception. (6 September)

As I Descended by Robin Talley

This YA paranormal Macbeth-inspired tragedy features a boarding school, queer love triangle, and chilling blur between the real and the imagined. (6 September)

Girl Mans Up by M-E Girard

YA still doesn’t excel at showing stable, happy queer relationships — but Girl Mans Up does. Through Pen and her conservative Portuguese family, her bullying childhood friend, and her hot new crush, this queer YA novel features questions of gender, sexuality, family, friendship and loyalty. One of Malinda Lo‘s favorite YA books about lesbian, bisexual and queer girls. (6 September)

Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova

Córdova draws on Latin American magical folklore to tell the story of Alex, a teenage bruja who wants to give up her powers and live a normal life. When she casts a spell to send them away, she sends away her family instead and has to fight to bring them back and find herself. At Book Riot, Nicole Brinkley notes: “Brujas! Family love! Creepy monsters! Girls who love girls! A boy made of sunlight! Zoraida Cordova’s Labyrinth Lost was a fun and fast-paced venture through another world.” (6 September)

Boss Babes: A Coloring and Activity Book for Grown-Ups by Michelle Volansky

Adult coloring books are having a moment. Why not combine feminist theory, Beyoncé and facts about the notorious RBG with coloring and short activities? (6 September)

Not Your Sidekick by C.B. Lee

In a world where everyone has superpowers, internships are really complicated — and for Jess Tran, they get more so when she lands one with a supervillain alongside her long-time secret crush. A second crush, a mysterious figure, and a dangerous plot soon follow. (8 September)

Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation by Carolyn Cocca

Women superheroes, still a scarcity, have become a way to discuss gender, race, sexuality and ability. Cocca examines why they’re a rarity, how they’ve evolved over time, and why they’re important to cultural gender narrative. (8 September)

even this page is white by Vivek Shraya

Toronto trans artist and activist Shraya‘s debut poetry collection renders visible everyday racism; what it means to be racialized; and the origins, functions and limitations of skin. (13 September)

Avie’s Dreams: An Afro-Feminist Coloring Book by Makeda Lewis

Incorporating a narrative of race, gender, sexuality, and body image, this adult coloring book “investigates the trials and magic of a young black girl growing up in the world.” (13 September)

Black Wave by Michelle Tea

This genre-bending fiction-memoir-meta-poem is a look at art, love and the apocalypse from the author of Valencia. Maggie Nelson, author of The Argonauts, notes: “Somehow Michelle Tea has managed to write a hilarious, scorching, devastatingly observed novel about addiction, sex, identity, the 90s, apocalypse, and autobiography, while also gifting us with an indispensable meditation on what it means to write about those things—indeed, on what it means to write at all.” (13 September)

A Life In Trans Activism by A. Revathi and Nandini Murali

In this memoir, Revathi plots her journey as a trans activist, including her time at a trans-focused NGO, her research, her travels in India and around the world, and her efforts to amplify the voices of trans and nonbinary people. (15 September)

Building Fires in the Snow: A Collection of Alaska LGBTQ Short Fiction and Poetry edited by Martha Amore and Lucian Childs

This collection investigates queer identity in Alaska from the perspective of many different backgrounds, viewpoints and experiences. (15 September)

Feminist Futures: Re-imagining Women, Culture and Development edited by Kum-Kum Bhavnani, John Foran, Priya Kurian and Debashish Munshi

How have women in the Global South transformed our ideas of development? In this updated collection, leading academics and new activists and scholars use the intersection of women, culture and development as a lens to examine sexuality, the environment, technology, the cultural politics of representation and more. (15 September)

Connexions: Histories of Race and Sex in North America edited by Jennifer Brier, Jim Downs and Jennifer L. Morgan

How do race and sexuality intersect in American history? This volume explores same-sex sexual desire and violence within slavery, whiteness in gay and lesbian history, how sexualized bodies were used to shape ideas of race and racial beauty and more. (15 September)

Ask Me About Polyamory: The Best of Kimchi Cuddles by Tikva Wolf and Sophie Labelle

This webcomic about polyamory, queer and genderqueer issues is now in print-book form. With discussions of practical, serious, and entertaining issues, Ask Me About Polyamory brings a multi-faceted approach to the many problems queer poly life can throw at us. (15 September)

Princess Princess Ever After by Katie O’Neill

Princess Amira rescues princess Sadie from her tower and the two become their own heroes and find happiness with themselves and each other. The original release of this book won Autostraddle‘s first Comic and Sequential Art Awards favorite graphic novel/book and Mey Rude wrote: “I’m so glad that there is a story like this that exists. The princesses don’t fit into the stereotype of the damsel in distress who wants desperately to be rescued by a prince. It has characters of different races and body types. It has two princesses who are their own heroes and don’t need to change who they are to save themselves and the day. It has a really cute queer couple. And all of this is in an all-ages comic.” (20 September)

Anybody: Poems by Ari Banias

In this poetry collection, Banias confronts the strangeness of being, of boundaries, and of a gendered, queer and emotive body. Maggie Nelson calls it “discursive, straight-talking, and thinky, then ghostlike, elliptical, and mischievous. It takes its time, then rushes; it’s quiet, then bold; it’s steeped in sociality, then ringing with solitude. I happily recognize its arrival, even if I know (as does Banias, quoting Berlant) that recognition may be but the misrecognition we can bear.” (20 September)

Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear… and Why by Sady Doyle

What does it mean for women to “behave”? Trainwreck is an examination of women culture destroys, from Mary Wollstonecraft to Whitney Houston, and what that destruction means. Andi Zeisler, Bitch founder, notes: “Some people take a scalpel to the heart of media culture; Sady Doyle brings a bone saw […] Trainwreck is a blistering indictment of how history has normalized sexism as entertainment, defining — and destroying — the women we claim to love.” (20 September)

Six by Julie Marie Wade

The poems in this six-piece collection are viewable from six possible shifting angles, examining six facets of human experience: art, language, desire, vocation, faith and love. (22 September)

Rad Women Worldwide: Artists and Athletes, Pirates and Punks, and Other Revolutionaries Who Shaped History by Kate Schatz and Miriam Klein Stahl

The authors of Rad American Women A–Z return with forty profiles and cut-paper portraits of women from history and around the world, including Hatshepsut, Malala Yousafzi, Liv Arnesen and Ann Bancroft, and more. Get a copy to every kid you know and keep one for yourself, too. (27 September)

Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin

Shirley Jackson, best-known for “The Lottery” and author of The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, has been often-overlooked within the American literary canon. In this volume, based on new interviews and discovered correspondence, Franklin examines Jackson’s focus on domestic horror and her own lived domestic horrors, and gives us, in Neil Gaiman’s words, “a way of reading Jackson and her work that threads her into the weave of the world of words, as a writer and as a woman, rather than excludes her as an anomaly.” (27 September)

Intimate Justice: The Black Female Body and the Body Politic by Shatema Threadcraft

Black women’s bodily and sexual freedom and autonomy has long been under threat. Looking at the antebellum slavery, Reconstruction, the nadir, and the civil rights and women’s movement eras, Threadcraft traces the route of black women’s intimate freedom and equality, and challenges prevalent ideas of freedom and equality in American race and gender relations. (3 October)

The Color of Kink: Black Women, BDSM, and Pornography by Ariane Cruz

BDSM and porn are sites from which to rethink the links between Black women’s sexuality and violence. With personal interviews with porn performers and producers and dominatrices, visual and textual analysis and archival research, and using feminist and queer theory, critical race theory and media studies, Cruz looks at Black women and BDSM from the 1930s to today and “explores how violence becomes not just a vehicle of pleasure but also a mode of accessing and contesting power.” (4 October)

I’ll Tell You In Person by Chloe Caldwell

“Growing up I loved personal stories and true stories. In my late teens I’d read the essays in The Sun Magazine, because my mom had a subscription. The essays would often be about sex and drugs and death and break-ups, and I was into it. I was moved,” notes Caldwell in an interview at Lambda Literary. In this collection of essays, she mines those same topics, as well as first intimacies, career struggles and the many imperfect approaches to adulthood. (4 October)

No Tea, No Shade: New Writings in Black Queer Studies edited by E. Patrick Johnson

In this essay collection, scholars, activists, and community leaders explore black gender and sexuality through discussions of “raw” sex, porn, the carceral state, gentrification, gender nonconformity, queer art and more. No Tea, No Shade both exemplifies the black queer experience while pushing black queer studies in new directions. (7 October)

A Greater Music by Bae Suah

This novel from Bae Suah, one of the most highly acclaimed contemporary Korean authors, is newly translated by Deborah Smith, known for her work on The Vegetarian. When the narrator falls into an icy river, her memories begin to shift between the present with Joachim, her metalworking boyfriend, and the past with a woman called M, a German teacher who was once her lover. Music, language, literature, and emotion are at the fore. (11 October)

Upstream by Mary Oliver

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Oliver’s appeal has been described as “her sharp eye, her tugs of emotion as she relates the outer world to a deeper interior experience” — qualities that are sure to appear in this essay collection. In Upstream, she positions herself as lost within the natural and literary worlds and meditates on a life centred on work and love. (11 October)

Tomboy Survival Guide by Ivan Coyote

In this collection of memoir-stories, Coyote — whose other collections include The Slow Fix and, with Rae Spoon, Gender Failure — discusses growing up in the Yukon, how they learned to embrace their tomboy past, and how they navigated the landscapes of gender. (11 October)

Future Sex by Emily Witt

In this history of the present, critic and journalist Witt examines porn, polyamory, the body, online dating, and other contemporary modes of connection and pleasure to paint an image of what women’s sexuality could be. Eileen Myles and Sheila Heti are all about it. (11 October)

Goldie Vance Vol. 1 by Hope Larson and Brittney Williams

Goldie is a 16-year-old girl who lives at a Florida resort her dad manages and dreams of becoming its in-house detective. When the current detective lands a case he can’t solve, Goldie gets a chance to step in. Mey Rude calls the series “absolutely irresistible.” (11 October)

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood

Pride of Canada Margaret Atwood retells Shakespeare’s The Tempest in Hag-Seed, a novel following a stage director putting on The Tempest in prison. The novel is the latest in the Hogarth Shakespeare series, which also included Jeanette Winterson‘s Gap of Time and Anne Tyler‘s Vinegar Girl. (11 October)

Kamala: Feminist Folktales from Around the World edited by Ethel Johnston Phelps, Suki Boynton and Kate Schatz

This anthology of classic folktales from across time and place positions women’s bravery, intelligence and power at the narrative centre. Reissued from Phelps’s collection and illustrated by Boynton, these stories remind us that women have power apart from patriarchy. (11 October)

Dead Feminists: Historic Heroines in Living Color by Chandler O’Leary and Jessica Spring

This visual book combines feminist history, feminist future, and letterpress inspiration in 27 profiles of women who have changed the world, including Sappho, Virginia Woolf, Fatima al-Fihri, Rywka Lipszyc and more. (11 October)

The Secret Loves of Geek Girls: Expanded Edition edited by Hope Nicholson

This non-fiction prose, comics and illustrated anthology depicts the live of over fifty creators and fans of comics, video games and sci-fi. Its contributors include Margaret Atwood, Mariko Tamaki, Marguerite Bennett, Noelle Stevenson and more. (18 October)

A Thin Bright Line by Lucy Jane Bledsoe

Based on Bledsoe’s aunt’s story, this look at queer life in the Cold War era follows geology editor Lucybelle Bledsoe as she accepts a government climate research position and the compromises to her identity it will entail — until falling in love makes things more complicated. Rabih Alameddine notes: “Bledsoe’s writing is intelligent, unadorned, and unsentimental, which allows us to look at a difficult time in American history with clarity instead of nostalgia.” (18 October)

Cakewalk: A Novel by Rita Mae Brown

Brown is best-known as the author Rubyfruit Jungle, an iconic lesbian coming-of-age novel that Emily Danforth says “made me conceptualize just how many ways of being were available for a girl who liked girls — beyond my family, beyond my town.” Set in interwar Runnymeade, a small town that straddles the Mason-Dixon Line, Cakewalk is a lesbian-centric family saga that explores love, sin, virtue and more. (18 October)

Feminist Spirituality under Capitalism: Witches, Fairies and Nomads by Kathleen Skott-Myhre

Women’s spirituality has been important both throughout history and also in the contemporary socio-economic landscape. In this academic volume, Skott-Myhre looks at how psychology and psychiatry relate to the oppression of women, and sees women’s spirituality as a political force that can forge a path forward in feminist and critical psychology, resistance, and alternatives to capitalism. (22 October)

Float by Anne Carson

Carson, a “poet of perversities” best known for Autobiography of Red, returns with a new collection of poetry in which she explores beauty, loss, memory and myth with her signature challenge to language and form. Presented as individual chapbooks to be read in any order within a transparent case, Float “kaleidoscopically illuminates the uncanny magic that comes with letting go of expectations and boundaries.” (25 October)

Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

This poetry collection from self-described queer Black troublemaker and Black feminist love evangelist Gumbs conceives of poetry as a tool of feminist theory and examines the lives of Black women who seek freedom from racism and gendered violence. Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley, author of Thiefing Sugar, calls it a “luminous, heartbreaking work.” (28 October)

Marian by Ella Lyons

A gender-flipped Robin Hood retelling centering on Maid Marian, Ella Lyons’ queer YA novel is full of sword fights and swooning. Marian is a country girl forced to move to the city of Nottingham with her father, Sir Erik. Robin is a farmer’s daughter with her eyes set on becoming the first woman knight in the king’s army. They become fast friends, and then something more. (3 November)

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

The author of On Beauty, White Teeth, and NW returns with a novel set in North-West London and West Africa. Swing Time examines two girls’ friendship, tap dancing, blackness, roots and time. It has already been described as “dazzlingly energetic and deeply human.” (15 November)

Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Julia Scheele

The histories of queer thought and action come to life in this non-fiction graphic novel, which shows the foundation of contemporary ideas on sex, gender and sexuality; how they are enmeshed in culture; and where we can challenge them. (Bleeding Cool has a sneak peak.) (15 November)

21 Questions by Mason Dixon

Kenya Davis is great at hiring but bad at dating. Simone Bailey is great at bartending, at music, and at getting women’s attention — which is why it’s so perplexing that she can’t get Kenya’s. She resolves to get closer to her, one question at a time, in this queer romance. (15 November)

Of Fire and Stars by Audrey Coulthurst