Dr. Martin Luther King and the Ferocious Possibilities of Black Liberation in Our Darkest Hour

I’ve been staring at this blank screen all day. For the past five days, actually. Traditionally on Martin Luther King Day, I write some form of a reflection. It’s ironic that in a time we’re facing that has never more closely mirrored King’s — I find myself most adrift from his words.

I say his words because it is his words that have so often been called upon in to soothe a nation that still searches for its soul. Familiar words taught to me in childhood that once brought solace — “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you have to do, you keep moving forward” — now leave me cold and distant. I know “the arc of the moral universe is long” and was certainly never naive enough necessarily to believe in a Dream, but damn I didn’t know it would hurt like this.

I don’t mean to sound self-pitying. The Civil Rights Movement itself was defined by uproar and awakening. There’s nothing — not a pandemic; not nationwide uprisings after the continued state-sanctioned murder of Black people by the police; not seven-hour waits at ballot boxes and legal elections being questioned and irreparably damaged by a white supremacist who stokes racial unrest; not even insurrection — that’s worse than what Black people have fought and faced down and banished before. But I’d hoped by now that we’d at least be fighting newly cloaked battles in new ways, not a flat circle of the exact same battles in the same exact ways. King said “we’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end,” a mantra he proved true with his own life. 12 days ago I watched as a Confederate flag marched through the Capitol, a feat that wasn’t even accomplished during the actual Civil War, and even though I know (I know) it’s awful, I couldn’t stop myself from thinking: What the hell did he give it all for?

Less than six days before this Martin Luther King Day, Ayana Pressley, a Black woman representative from Massachusetts, one of the most powerful advocates for Black and brown people speaking up in Congress right now, announced that in the days before a lynch mob descended on the U.S. Capitol, all of the panic buttons in her office had been ripped out. Her Puerto Rican colleague, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who much like Pressley has become somewhat infamous in hate mongering white supremacist circles, openly feared for her life. And here’s what I can’t stop replaying: Representative Pressley’s response to this violence? These experiences “were harrowing and unfortunately very familiar in the deepest and most ancestral way.”

The deepest and most ancestral way. Latosha Brown, one of the fierce Black women organizers in Georgia who just finished a momentous feat overcoming white supremacist tactics of voter suppression with her organization, Black Voters Matter — a cause King laid down the blueprint to fight for over 60 years ago — reminded us on Dr. King’s birthday just this Friday: “The same energy that killed him is the same energy that we witnessed at the Capitol.”

It’s feels impossible not to see this Martin Luther King Day as one of grief and mourning.

But Black liberation politics is one of turning impossibilities into stubborn realities. I mean, someone once told enslaved people it was impossible they’d be free. And so, while I am immensely grieving how clear it is now how much work is actually left, how little it feels like we’ve come as nooses are hung outside the Capitol building and Twitter threads are full of Black people warning each other to “stay at home, stay safe” like we’re whispering into the wind, I’ve realized that the reason I couldn’t write this essay was that I was looking in the wrong place. We don’t need Dr. Martin Luther King’s words — we need his actions.

On Wednesday there will be a new President, and he will be a Democrat. That is no reason to rest; it’s only a reason to push harder. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 happened under a Democratic President. The original Voting Rights Act of 1965 happened under a Democratic President. Dr. King and was a never-ending thorn in Lyndon B. Johnson’s side — an exceptional political organizer and strategist — and so too, should we. And even that will only be a start.

The good news, the best news even, is that we have already been doing that. The key is in not letting up. To recognize these newest waves of vitriolic flames of hatred as also a marker of our work. Dragons breathe the hottest fire when they feel threatened. And good. Let them.

This morning, I thought a lot about another Black organizer, a mentee of King who was only 23 when he was not only one of the lead organizers, but spoke at the March on Washington. Who was 25 when police brutally beat him on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in a march for voting rights which he led. Another giant lost in this agonizing year.

John Lewis left us on July 17, 2020 — in the middle a summer defined by uprisings for Black Lives — but his final goodbye was not published until the morning of his homegoing service. In it, he wrote a public letter to Black Lives Matter organizers: “Emmett Till was my George Floyd. He was my Rayshard Brooks, Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. He was 14 when he was killed, and I was only 15 years old at the time. I will never ever forget the moment when it became so clear that he could easily have been me. In those days, fear constrained us like an imaginary prison, and troubling thoughts of potential brutality committed for no understandable reason were the bars.”

Of course, those days are also now, he realized. But unlike me, he didn’t become brokenhearted. Instead, he found peace knowing the work would continue. It will always continue, as long as we don’t let the fire die out.

“While my time here has now come to an end, I want you to know that in the last days and hours of my life you inspired me. You filled me with hope about the next chapter of the great American story when you used your power to make a difference in our society…

That is why I had to visit Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, though I was admitted to the hospital the following day. I just had to see and feel it for myself that, after many years of silent witness, the truth is still marching on.”

It’s funny. So often we talk about how Dr. King — or John Lewis, or Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, so many who others have walked before and are now immortalized — are more than their black and white photographs and grainy newsreels. But we’ve never less needed paper doll cutouts of revolutionaries than we need right now.

In our upheaval, soft words will not save us. Look to the playbook instead.

A Black, Queer Reflection on The Civil Rights Movement and the Unfinished Project of Freedom

This piece was originally published on 01/15/18

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual, which includes celebrating Pride. This week, Autostraddle is suspending our regular schedule to focus on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle. And so we must straighten our backs and work for our freedom. – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

It’s not the most famous Dr. King quote, the one that get dusted off year after year. That honor goes to those three little words that we can all recite by memory, “I have a dream…”. It’s not even the quote that I’ve used most often in my own life, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that”.

No, this quote is hard. It isn’t popular to remember that change is not inevitable. It requires unrelenting struggle and work. It’s not sexy. It’s not even particularly optimistic. There is no Happily Ever After. Instead, Dr. King only promises a future in which we must bear down, straighten our backs, and keep carrying our load. This quote challenges me, it sticks to my bones. I’m not sure that I like it.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was not a perfect man. He was someone who fought hard for racial and economic justice. He gave his life for it. And for that, he became immortalized. He became stuff of legend. My first grade teacher made my entire class memorize the opening paragraphs of his “I Have A Dream” speech, we delivered it at a school assembly. My high school required that we spend our day off from school honoring his birthday by completing community service projects. As I type this short essay, my neighborhood’s annual “MLK Day Parade” is happening outside my window.

I once tutored a college freshman, this black kid who was a rookie star on the football team and in serious danger of failing his “Intro to African American History” course. At the start of our first session together, I asked him what he had learned in his 18 years about black history. He replied, “Well, we were slaves, and that was bad. But, then Dr. King freed us and ended racism”. Dr. King freed us and ended racism.

I was stunned. He knew that racism wasn’t really over in this country. He was an 18-year-old black boy who grew up in the South. Of course he knew that. But, he also didn’t know where else to look or who else to point to. It broke my heart, because I knew that was by design.

After a long and difficultly fought battle, Dr. Martin Luther King Day was first celebrated as a federal holiday in January 1986. Since then, every third Monday in January, posters are hung in civic center windows and children are let out of their schools. Politicians who otherwise never spend a day pondering racial justice in America have their speechwriters hastily throw something together. I’m thankful that we take time to honor a racial justice leader in this country at all, but the danger of Martin Luther King Day is that it erases the flawed person behind the legend. It also erases the remaining work that each of us has to roll up our sleeves and complete, because the prophecy of King’s “beloved community” is far from coming to fruition.

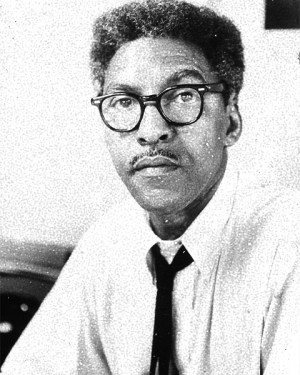

Bayard Rustin

Those erasures can be particularly fraught for black queer women and queer folks of color. Martin Luther King did not treat all the women in his life with respect, it’s well documented that he habitually cheated on his wife. Many black women in the civil rights movement found leadership roles in King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and similar organizations, but have also testified to the difficulties of working around the accepted patriarchal social norms of the time period. There were two out black gay male leaders at the SCLC, most famously Bayard Rustin, who was the lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. Despite enjoying a close working relationship, King eventually distanced himself from Rustin at the urging of other civil rights leaders. To consider the full breadth of his legacy, we must grapple with these, and any other, shortcomings.

But, we also must keep King’s memory free from those who wish to pacify him and use him to uphold conservative values against the ongoing fight for social justice in this country. In recent years, Republican and Democrat politicians alike have invoked King’s words to chastise the Black Lives Matter movement. This year alone, we have to look no further than the current President of the United States signing the 2018 Martin Luther King Day proclamation less than 24 hours after spewing disgusting, hate-filled, racist remarks aimed at black and brown diasporas. The national observation of Martin Luther King Day often works in service of those in power. If King’s work is seen as completed, then those who pick up the fight towards freedom are seen as disrupting, or worst, besmirching, his legacy. It’s a dangerous, ahistorical rhetoric that ought to be be upended at every turn.

King himself reminds us that change will not come without the labor of never ending hard work. Change will not come while we wait for someone “perfect” to lift the hammer. He spoke of the radical notion of a “beloved community”, that people should band together in the name of equality, regardless of race, gender, sexuality, representation or ability. Anyone who has been a part of a family, blood or chosen, knows that communities take real effort. They require listening to ugly truths, and fighting, and be willing to humble yourself. They require not putting your individual conveniences ahead of the larger group, the most vulnerable among you.

“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle. And so we must straighten our backs and work for our freedom.”

– Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

They also require constant maintenance. You cannot wash your hands of your community and declare the project done. There will always be another battle, another family member who needs your help. It’s exhausting, but restorative. Taking care of each other — putting in that sweat together — is how King believed we would curve the long arc of history towards justice.

Fannie Lou Hamer

The community that King surrounded himself with included fierce, brave, warriors of women like Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer. A former sharecropper, Fannie Lou Hamer famously stood up at the 1964 Democratic National Convention and testified that she was tired of working in service of an unfinished project of America that she questioned more than she believed in. Still, she never gave up. Ella Baker, a mentor of Rosa Parks, was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s first full time staff member. She went on to become one of the founding members of SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee). She also ran an essential voter registration campaign across the south, called the Crusade for Citizenship. Her career as an activist spanned five decades. She never gave up.

Ella Baker

By the time Bayard Rustin was recognized for his work in the civil rights movement, with a Presidential Medal of Freedom, he had long passed away. His loving partner, Walter Neagle, accepted the honor on his behalf and listened as President Obama declared that at a time, “when many had to hide who they loved… Bayard Rustin became one of America’s greatest architects for social change and a fearless advocate for its most vulnerable citizens”. He never gave up.

Today, I honor Dr. Martin Luther King by also honoring their work. The work of civil rights history is queer and feminist. It’s bigger than one man. It’s a hard, rough, incomplete project. And so, we must lock our knees, we must straighten our backs. We must never give up. We must keep working, always working, for our freedom.

What Can Black Queer People Learn From the Lost Queer Joy of the Civil Rights Movement?

I didn’t know Martin Luther King was human until I was already well out of high school.

That sounds awful, and would embarrass the people who raised me, let me try again:

I grew up as a “well behaved” Black girl in metro Detroit, which means that I firmly grew up within the shadow of Martin Luther King’s myth. If you’re Black, and especially if you’re Black and grew up in a major Black city any time in the last half century, you know the drill. You know the speeches, and the church breakfasts, the symbolic marches, and the documentaries. You know the service projects. You learn “I Have a Dream” well before most of your white peers, and by the time they’re finally covering the scrapped together basics of the civil rights movement, your parents have already so deeply instilled in you that you have to be twice as good to get half as much that Dr. King’s dream might as well just stay that — a dream. The King I knew was an icon. A martyr. Depending on whom you ask, a savior. But he was never a human being.

Usually when people talk of Dr. King’s humanity, they zero in on the ways he was fallible. They speak of his numerous affairs behind his wife’s back; they note that he didn’t do enough to stand up for one of his lead organizers, Bayard Rustin, when he faced rampant homophobia; sometimes they even mention that Dr. King enjoyed a bit of gambling on the side. What you hear less often is that he was only 26 years old when he led the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He was 34 at the March on Washington. He hadn’t even reached 40 when he was assassinated. Martin Luther King was a young man.

The first time this really occurred to me, it was because of a photo of Dr. King flirting with his wife, Coretta. It looks like it’s cold outside and she’s kissing him on his cheek, her gloved hand rested on his shoulder. His eyes are larger than usual, turned to the upper corner as if to put on a performative “aw shucks.” It’s silly and playful. I’ve seen hundreds photos just like it from couples on Instagram.

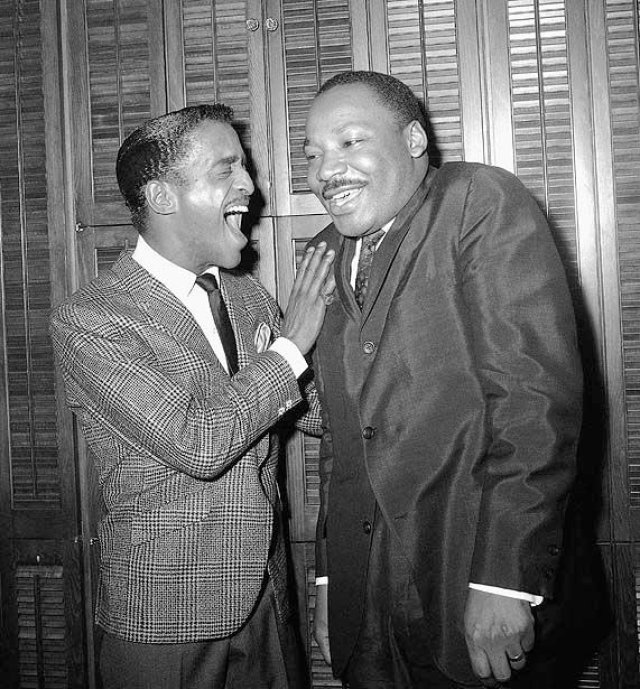

The next time I thought about how young Martin Luther King really was, it was when I saw him in a corner pressed against the performer Sammy Davis Jr. Sammy’s mouth is open so big with laughter, it’s almost doubled. King’s shoulders have hunched up so far, they’re at his ears. They’re definitely spilling some kinda tea, and it is HOT. There’s so much joy there, but looking at the picture makes me almost sad. Why was I an adult before someone bothered to tell me that Martin Luther King ever laughed?

Y’all I am tired.

There’s an expectation — on days like Martin Luther King Day or Black History Month, specifically — that Black folks — especially the Black folks who occupy liberal “woke” circles, like the kind often occupied in queer communities — will spend the day teaching. And to be fair, I’ve made my career teaching Black history. I joke that “Martin Luther King Day through February 28th is when I make most of my coin all year.” So, I definitely signed up for this and I knew what the deal was when I penned my signature. But, more than anything, this year, I want to wish Black queer and trans people joy. Martin Luther King didn’t fight that damn hard for us not to have a quality of life that comes with celebrating our joy and humanity first.

The desire to find footprints of something gay and happy and Black to write about led me back to Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin. Two Black queer writers whose friendship and intellectual partnership have become a myth of its own right. A Black gay man that for many QTPOC, “venerable” would only be the beginning — an understatement of what he’s meant to us when words stop having meaning. To Lorraine, he was Jimmy. She was closeted lesbian playwright and essayist whose most famous work, A Raisin in the Sun, is still performed by high schools in every city nationwide, so much so that it borders on cliché. He simply called her “Sweet Lorraine.”

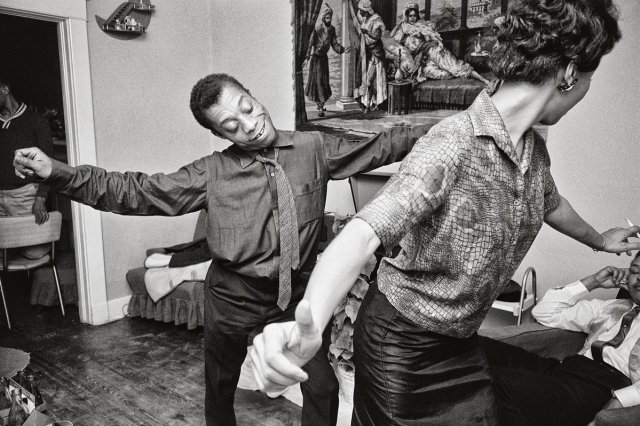

If you’re a Black queer nerd (or perhaps even if you’re not) there’s a photo that’s probably being conjured in your mind right now. In it, James Baldwin’s smile takes up half his face. His arms are wide. His tie’s askew. His hips are rocking to beat that, even in a still image, you can somehow hear. Lorraine is facing away from the camera, snapping her fingers to the same tune. She doesn’t let go of her famous cigarette. It’s the kind of photo that gets shared every year on his birthday, on her birthday, whenever someone wants to spark a little fun on social media timelines.

Here’s something most people won’t tell you: That’s not Lorraine in the picture. It’s an unnamed CORE worker in New Orleans. The reason the photo is shared prolifically and is so closely associated to Hansberry and Baldwin, however, is because it perfectly encapsulates their friendship. Here they are, as described in Baldwin’s own words in the essay he named after her nickname, “Sweet Lorraine:”

We walked and talked and laughed and drank together, sometimes in the streets and bars and restaurants of the Village, sometimes at her house, gracelessly fleeing the houses of others; and sometimes seeming, for anyone who didn’t know us, to be having a knock-down-drag-out battle. We spent a lot of time arguing about history and tremendously related subjects in her Bleecker Street, and later Waverly Place, flats. And often, just when I was certain that she was about to throw me out as being altogether too rowdy a type, she would stand up, her hands on her hips (for these down-home sessions she always wore slacks), and pick up my empty glass as though she intended to throw it at me. Then she would walk into the kitchen, saying, with a haughty toss of her head, “Really, Jimmy. You ain’t right, child!” With which stern put-down she would hand me another drink and launch into a brilliant analysis of just why I wasn’t “right.” I would often stagger down her stairs as the sun came up, usually in the middle of a paragraph and always in the middle of a laugh. That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister.

That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister.

You know the phrase a picture is worth a thousand words? Well this might be one of those few times when the words do it better.

It’s the rowdiness. The unbridled laughter, so loud that others would mistake it for a fight. The hands on the hips and name calling. The stumbling home at dawn that still doesn’t feel like an ending, only an ellipsis of what’s next to come. That’s the story I want to talk about today.

James Baldwin was at the March on Washington, of course — as was almost every other Black person with even a modicum of intellectual or political celebrity (ironically, Lorraine Hansberry was not; she was at home recovering from surgery). Those famously drawn moments, with their stoic black and white photographs and stern promises of a better tomorrow, are important. Their performance of “respectability politics” that asked Black activists to wear their supposed Sunday best for long walks in blazing sun as a proof of their humanity for white people who never gave them a second thought in the first place — that’s important. Those are stories of heroes that I learned as a child, and I don’t take them for granted. Not for a second. And most certainly, not on this day.

But this? This after-hours queer mess, full of sweat and entangled limbs and exuberant slurred words? These stories of bossy femmes in slacks who made a home out of their kitchen for their smartass friends to bang tables and talk loud? Of Black queer folk who loved on themselves in the middle of the night, and together built a family of children that, nearly 60 years later, they’d never get to meet? That’s what I find myself most clamoring to remember.

It’s not about who we are when the cameras are turned on, but the ways we care for each other when no one is looking but us. When we’re exhausted from this fight. When we have to promise ourselves that we’re worth it right now. When kisses and laughter are our ports in the storm.

Martin Luther King Day Roundtable: What’s In Your Black Justice Toolkit?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is often co-opted and remembered as a pacifist, but he was a fighter for black liberation above almost all else. That’s the legacy that Autostraddle is remembering. On this holiday, we’re honoring his work by asking ourselves: What’s in your Black Justice Toolkit, right now?

What are the intellectual, emotional, physical “tools” that you’re using to fight for justice in black communities? What are the tools that you think we need to be building? Simply put, what does black liberation look like for you, and what are you prepared to do to get there?

We invite you to join our conversation in the comment section.

How Coretta Scott King Leveraged MLK’s Legacy to Fight for Gay Rights

“I once told Martin that although I loved being his wife and a mother, if that was all I did I would have gone crazy. I felt a calling on my life from an early age. I knew I had something to contribute to the world.” Coretta Scott King, quietly known as the First Lady of the Civil Rights Movement, is most famous for being her husband’s wife. She’s seen in photos more than she’s ever heard in video. She’s remembered as elegant, demure, classy, perhaps even stoic in her strength.

Despite, as King biographer Clayborne Carson once put it, being “more politically active at the time they met than Martin was,” she’s often more discussed for her iconic Jackie Kennedy level wardrobe than for leading more than 50,000 marchers through the streets of Memphis just four days after her husband’s assassination. Three of her four children were by her side.

On the most famous day of Dr. King’s legacy, the 1963 March on Washington, Coretta Scott King sat silently in the second row. According to the Smithsonian’s oral history of the march, she was mentioned only once that day, in passing, despite a lifetime of investment in racial justice dating back to her teens. As a college student she was a member of the NAACP and the Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. In his early letters to her, Martin noted that his first attraction to Coretta was her political mind. He thought of their love as a partnership.

That partnership wasn’t always equal. Much like the other women who were, by Scott King’s own estimation, the “backbone of the whole civil rights movement,” she was expected to work in shadows. Ella Baker, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer and so many more have only recently begun to be given their proper due in history. For Scott King, the process of coming to the public light began in the days after her husband died.

Coretta Scott King with her children at the funeral service of Martin Luther King, Jr.

On April 8, 1968, four days after Dr. King’s death in Memphis, Coretta Scott King flew to the place of his murder and lead a protest memorial in a black lace headscarf. She’s reported to have said, “I need to go finish his work. I’ve been with him as a partner on all these other marches and confrontations. I feel like I need to go.” Her eulogy at his funeral was televised to more than 120 million people. Three weeks later, she delivered his planned speech at a protest against the Vietnam War in New York’s Central Park. Two months after that, she led the Poor People’s March to Washington in her husbands name. King had originally conceived the march in hopes of forcing the US government to confront the realities of American poverty. Coretta’s analysis highlighted intersections of class, race, and gender that often kept black women poor and undervalued.

She went on to become the first woman to preach at Great Britain’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the first woman to deliver the class day address at Harvard University. She created the Full Employment Action Council and the Coalition of Conscience, two governing bodies that brought religious organizations, businesses, and human rights groups together to work in favor of national policies on access and equality. She founded the Martin Luther King Jr Center for Nonviolent Social Change, a cornerstone of her and her husband’s lasting legacy. For Scott King, an key part of that legacy was carrying King’s name into the fight for LGBT equality.

In 1983, on the 20th anniversary of her husband’s March on Washington, Scott King pledged her support for the Gay and Civil Rights Act that was then before congress. The groundbreaking bill would have prohibited discrimination against gays and lesbians in housing, employment, and other public accommodations protected by federal policy. When questioned about this turn in her activism, Scott King reminded naysayers that many gays and lesbians had given their all to the civil rights movement (including perhaps most famously Bayard Rustin, an openly gay black man and lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington). She felt it was her duty to offer support in return. Later that year, Scott King purposefully made space for black lesbian poet Audre Lorde at the march’s anniversary rally. The good Lorde spoke:

Today’s march openly joins the black civil rights movement and the gay civil rights movement in the struggles we have always shared, the struggle for jobs, for health, for peace and for freedom. We marched in 1963 with Dr. Martin Luther King and dared to dream that freedom would include us, because not one of us is free to choose the terms of our living until all of us are free to choose the terms of our living.

In the mid-1980s, when President Ronald Reagan wouldn’t even acknowledge the disease, Scott King – with the help of her assistant Lynn Cothren, an openly gay man — used the King Center to create a welcoming environment for the LGBT community, especially queer black people who were suffering in the middle of a generational genocide from HIV/AIDS. After the death of a close gay friend, she hosted a day of memorial at the Center and encouraged participants to sew stitches on a panel that would become part of the AIDS memorial quilt.

In 1986, in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Bowers v. Hardwick that there was no constitutional right to engage in homosexual sex, Scott King accepted an invitation to be a featured speaker at the September 27, 1986 New York Gala for the Human Rights Campaign Fund. In 1993, she held a press conference urging President Clinton to end the ban on gays serving in the military. In 1994, she stood with Senator Ted Kennedy and Representative Barney Frank as they introduced the Employment Non-Discrimation Act (ENDA), which among other things would have prohibited workplace discrimination on the the basis of sexual orientation.

On March 31st 1998, at the 25th Anniversary luncheon for the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, King spoke out against strands of conservatism in black communities that had kept some members reluctant to join the gay rights movement. She stated, “I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people and I should stick to the issue of racial justice… but I hasten to remind that Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream to make room at the table of brotherhood and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people.”

The next day, April 1st 1998, at the Palmer House Hilton in Chicago, she added: “Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood.” She echoed these sentiments time and again until her passing.

In 2004, during the middle of a heated national debate on same-sex marriage and a proposed constitutional amendment endorsed by President George W Bush that would have defined marriage as between a man and a woman, Coretta Scott King spoke out again. She called the proposed amendment tantamount to “gay bashing.”

While her eldest daughter, Yolanda King, took up Coretta’s mantle of activism for gay rights, her youngest daughter, Bernice King chose a different path. In the middle of the same 2004 debate for marriage rights, the younger King besmirched that her father “did not take a bullet for same-sex marriage.”

In part these comments fueled a fire between the King siblings, pitting Yolanda and Dexter against the more conservative Martin Luther King III and Bernice. After their mother’s passing in 2006, the siblings fought over the sale of the King Center in Atlanta. The dispute was ultimately settled by Yolanda’s untimely passing due to complications from a chronic heart condition in 2007. Currently, Bernice King remains the CEO of the Center.

Still, the legacy of Coretta Scott King’s lifetime commitment to the hard work of social justice cannot be overturned. Last year on Martin Luther King Day, I reflected that the work of justice never ends. The only way forward is for everyone to roll up their sleeves and fight another day. It’s uncomfortable, off-putting, and absolutely necessary. No one better embodied that message than Coretta Scott King, who spent the 40 years after her husband’s passing not laying back and honoring him peacefully. Instead, she fought every day. And for those last 20 years? She fought for US.

Coretta Scott King understood how she was best remembered, that many were satisfied to consider her a relic of the past. She then turned that legacy on its head, “I am made to sound like an attachment to a vacuum cleaner, the wife of Martin, then the widow of Martin, all of which I was proud to be. But I was never just a wife, nor a widow. I was always more than a label.” She leveraged the weight of her husbands name and, in the true spirit of an ally, never asked for a thank you or a spotlight as she hefted that name in our corner so that we could build on his good work.

I cannot think of a better memorial for her husband than to honor her today.