Los Angeles Gay Bar The Abbey Faces an Overdue Reckoning

Feature image by FG/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images via Getty Images

This piece contains frequent reference to sexual assault.

I went to The Abbey for the first time in early 2019, a couple months after moving to Los Angeles.

New to the city and looking for queer community — and, let’s be honest, some post-breakup partying — I typed in lesbian bar on Yelp. I followed a mostly empty page advertising “Girl Bar” that ended up just being a defunct offshoot of The Abbey. Already there, I got a drink and did my best to talk to the few queer women amidst the crowd of cis gay men and straight people.

During my first year in LA, this was always the role The Abbey played. Nowhere else to go? Well, fine, let’s go to The Abbey. There are better gay bars on that very block, but with its size, lack of cover charge, and mix of genders — even if many were straight — it was a natural place for desperate queer women with limited options to end up.

But, from the beginning, I’d heard the rumors.

Spoken about with a regretful shrug, like the bar was a predatory actor still winning awards, people passed along warnings about The Abbey. Everyone seemed to know someone who had been drugged.

Open secrets — even ones that reference multiple lawsuits — are only so effective. That’s why it’s both upsetting and a relief to read the recent report on these incidents by Kate Sosin and Steven Blum for The 19th.

“More than 70 people interviewed by The 19th over the course of three years reported going to The Abbey… and experiencing disorientation to varying degrees or losing consciousness,” they write.

The piece goes on to highlight several of these incidents including Yvette Lopez who sued The Abbey in 2013, claiming she was drugged by an employee and then sexually assaulted, and Haely White, an actor and comedian who was sued by The Abbey after posting on Instagram in 2021 about being drugged. (Lopez settled; White is still fighting, “buried in legal fees.”)

It’s notable that most of the women who were drugged at The Abbey are queer. Since many of these incidents took place, bars like The Ruby Fruit and Honey’s have opened, but for years Los Angeles was completely devoid of lesbian bars. There are more dire consequences than boring nights when a lack of spaces exist for queer women and trans people.

This is emphasized by the fact that White was outed by The Abbey when they released a message exchange of White explaining she was on a date with a woman, even though she’s married to a man. “I was framed as a liar,” White said. The truth was her husband knew about the date — they weren’t monogamous even if she wasn’t ready to come out publicly.

Lopez also faced skepticism about her queerness — this time from detectives. She eventually dropped her case, because it was retraumatizing with victim blaming and detectives questioning whether she was, in fact, a lesbian.

Incidents such as these are allowed to continue for so many years, because there is an incentive not to report. Many of the individuals who spoke to the police or even just to management at The Abbey were dismissed or worse. Even White has faced emotional and financial consequences just for posting on Instagram.

In response to one incident when a woman did not report, the piece states: The Abbey said it had no record of this incident and went on to say that “anyone who believes they are a victim of a crime should report it to the police.”

It’s astounding to see this requirement of law enforcement stated by a gay bar. There’s an immense ignorance to queer history and queer present in this demand. I’m not surprised, but I am sick to witness this politic stated so brazenly.

The last time I went to The Abbey, I didn’t go inside. It was June 2020, the day of West Hollywood Pride, and I was at a protest. I asked if I could use their bathroom and was informed only patrons having brunch were allowed to use their facilities. The peak of a pandemic, amidst protests against police brutality, and they wouldn’t let a trans woman take a piss.

I hope this excellent reporting and the brave women who have come forward result in The Abbey experiencing a long overdue reckoning. I also hope there continue to be more spaces available for queer and trans people where we can dance and get drunk and do drugs while also feeling a greater amount of safety and care.

It’s impossible to create a completely safe space, but The Abbey is, at best, complicit and, at worst, entirely responsible for over a decade of harm.

Moby Dyke Is a Fresh Take on the Old Conversation About Disappearing Lesbian Bars

I didn’t go to my first lesbian bar until I was in my early twenties. Whenever I tell people this, they assume it’s because I wasn’t out until then, but actually, I came out almost 10 years before that. In South Florida, where I was born, raised, and currently live, we are flush with gay bars and sporadic parties that “cater to” queer and trans people without always explicitly saying that, but lesbian bars have always been extremely rare. The one lesbian bar that was open when I was young closed in the middle of the aughts, and the one that opened just two years before the start of the pandemic closed for good in the early days of it. So, even before I came out as non-binary, I spent most of my life going to gay bars or mixed spaces or spaces that were neither because that was what we had and my friends and I still wanted to get drunk, do karaoke, dance, and have fun.

As Krista Burton notes in her new book, Moby Dyke: An Obsessive Quest to Track Down the Last Remaining Lesbian Bars in America, the death of the lesbian bar is a well-documented phenomenon. I have written and spoken on the topic here at Autostraddle and on the podcast that I co-host, and there’s writing on it in every publication from The New York Times to Smithsonian Magazine. The set up for most of the research done on the disappearance of lesbian bars is generally the same: What the hell happened to all of them? And then the same statistic from The Lesbian Bar Project is referenced: in 1980, there were over 200 lesbian bars operating in the U.S. and by 2021, the number of lesbian bars still open and operating was 24. Burton’s book starts out similarly, but doesn’t stop at speculation about why this might be or rely on prior research. Instead, Burton decides that to really understand why there are so few lesbian bars around now, she should visit 20 of the bars that remain open to try to understand why so many of them have closed.

The book chronicles Burton’s year-long journey to each of the 20 lesbian bars she chose to visit, and the knowledge she gained on her trips to each of them. She starts her trips most obviously in San Francisco, at Wild Side West, and New York City, at both Cubbyhole and Henrietta Hudson (our beloved Ginger’s was temporarily closed at the time of her trip), but then her search takes her to places that I think will be surprising to a lot of East Coast and West Coast queers: Slammers in Columbus; Lipstick Lounge in Nashville; Alibi’s and Frankie’s in Oklahoma City; Yellow Brick Road in Tulsa; Babe’s of Carytown in Richmond; and Herz in Mobile. Before she embarked on the journey, she set specific rules for herself — such as “I would contact the bar owners and try to interview them, settling for an employee or a regular if the owner couldn’t be reached” and “I had to approach and speak to at least two strangers at every bar” — which yield surprising and fascinating results for both Burton and the reader. The discussions she includes in her narrative of her visits are easily some of the richest, most important parts of the text, making it worth reading just for that.

Some themes pop up in her discussions with bar owners, bartenders, and people who go to the bar regularly. Many of them seem to parrot a lot of the explanations we get for the disappearance of lesbian bars elsewhere: There isn’t enough money in it, the bars have gotten more inclusive over the years (with many of them calling themselves, as Burton puts it, “lesbian bar[s] that welcomed everybody”) which is obviously a good thing but also impacts who comes and who has stayed a patron, and despite some of the progress we’ve made in our society over the last 43 years, it’s still hard as hell to be a female business owner or try to be one. These explanations aren’t very surprising to Burton (or me) but what is surprising are the responses to these explanations. The people Burton encounters aren’t upset or distraught about how open these spaces have become in terms of people of varying sexualities and gender identities necessarily. They have just noticed that as the world has become more accepting of queer people overall, queer people seem to have walked away from these spaces a bit. In one of Burton’s conversations with Lisa Menichino, the owner of the legendary Cubbyhole in NYC, Lisa says, “I think sometimes a lesbian bar is like an old friend you’ve spent a lot of time with and then drifted away from. Queers think of the bar fondly, and there’s a huge out-cry if one closes, but they forget that in order to have the bar, they need to come hang out there.”

Although the book starts out with a few common questions, Burton’s quest for understanding evolves as she keeps going on her lesbian bar trips. By the time she gets to Herz in Mobile, one of my favorite parts of the book, her exploration changes from trying to figure out why these bars keep closing to truly celebrating and trying to situate these spaces among what she already knows, understands, and loves about queer culture. At Herz, she comes face-to-face with many contradictions she doesn’t expect. As Burton explains in this chapter, Alabama has some of the most draconian anti-queer and anti-trans laws in the country and explains, “I can’t imagine it had been easy to be Black lesbians trying to open a lesbian bar” there. When Sheila Smallman, one of the owners of Herz and a former chief of police, tells Burton that the bar was actually well-received and widely accepted by the neighborhood it’s in, Burton is shocked and Sheila clarifies by adding what she thinks makes that possible: “We only have two rules in here. Number one: no politics. Number two: no religion, and we mean it!” The contradictions she encounters at Herz push Burton to grapple with different, more important questions about queerness and queer culture than she ever intended to, and realizes, “Everyone is someone you can’t put in a neat little box, of course, but it’s something that’s easy to forget. Hertz was special, I decided, not because of what it was, but because it was Sheila and Rachel’s bar, a space they had created for all of us, gray areas included, in a place where it’s amazing a lesbian bar even exists.”

As we move through the bars with Burton, we also move through some stories of Burton’s life as a femme lesbian coming from a deeply religious and difficult upbringing married to a trans man. Burton introduces us to her husband early on, and we get glimpses of her most impactful queer friendships as she travels from city to city and is reminded of certain pivotal moments in those friendships. These recollections and reflections serve as a kind of glue for all of the moving parts of this narrative and help answer the “So what?” question that might be on some people’s minds as they begin the book or try to get through it. Burton, as we find out through the revelations she included in the book, is genuinely invested in the survival of lesbian bars because that’s where she experienced some of the most important moments of her life so far, where she learned to be herself, and where she felt the most comfortable as a young queer trying to navigate a world that doesn’t want young queers to survive it. She also very thoughtfully includes some personal reflections on gender inclusivity and what that means for her and her husband as they visit these spaces and daydream about frequenting them more regularly. These pieces add the emotional weight that might be necessary for both queer and non-queer readers, especially younger ones, to understand why these spaces are so sacred to so many of us and why we lament the fact that there’s so few of them around.

By the time you get to the epilogue of the book, Burton notes that “The trajectory for lesbian bars is finally moving upward” and makes it a point to shout out the bars in Chicago and other places that have opened since she completed her trip. It serves as the optimistic end to a book already brimming with optimism about these spaces and their ability to stay open against all odds. Burton might not definitively answer all the questions she originally set out to, but what she does do is give us more reasons to keep believing in the power of collectivity and community and getting together with your queer siblings and partners at your local spot at the end of a tough ass day. At the end of the book, Burton reminds us: “It doesn’t matter what you wear. It doesn’t matter who you came with. What matters is you’re there. The only thing lesbian bars need is you.” And those of us who are able should heed the call.

Why Do Lesbian Bars Keep Disappearing?

Feature image by NoSystem images via Getty Images

On a recent episode of the research and education oriented arts and culture podcast I co-host, Fat Guy, Jacked Guy, I brought attention to something I think more people should care about and that’s been on my mind a lot: the gradual disappearance of lesbian bars here in the U.S.

LGBTQ history is an area that I considered myself very well-versed in, but when I began the research for that episode, I realized I didn’t know as much about the contemporary reasons (and excuses made) for their disappearances as I thought. I’ll admit my own experiences with lesbian bars is amateur-ish at best. I don’t have a long, personal history of going to lesbian bars, because of some of the reasons I’ll get into here, but also because of where I grew up and have lived my whole life.

I came out as gay to myself and to my friends when I was 14-years-old, and in response, some of them ended up coming out, too. Being young and queer in 2002 was a truly surreal experience. Although we were able to use the internet to gather resources and make some connections to other young queer people, there wasn’t really an easy or accessible way for us to truly learn more about ourselves, about the history of people like us, and about being queer in general. Often, we had to listen to people from BOTH SIDES, not just the far right or the moderate left, openly question and debate whether or not queer people deserved to be as protected under the law as they were. We had “allies,” of course, but that didn’t make things much easier when your high school history teachers were allowing kids to openly debate the merits of “same-sex” marriage in class. In addition to that, we had very few — almost none, actually — models of what it looked like to be a healthy and successful queer person in mainstream media.

My queer friends and I did have one slight, unusual advantage, though. Not too far away from where most of us lived, there was and still is a small “gay village” called Wilton Manors situated just north of downtown Ft. Lauderdale (actually, we did an episode on this, too, if you’re interested). Wilton Manors is the first place where I ever saw gay people in real life just acting like their gay ass selves. Men on the streets holding hands, wearing leather and bondage gear, kissing on street corners. Mostly men, though. Sometimes women, but rarely, and usually, it was because they were hanging out with a larger group of guys. There weren’t a lot of people of varied gender experience, either, which I guess speaks to both the time and the way the neighborhood used to be. But it was what we had, and by the time we were old enough to drive, we were hanging out in the coffee shops and, eventually and illegally, hanging out in the gay bars of Wilton Manors as much as we could.

There was one lesbian bar in Wilton Manors, but by the time it gained popularity, our trips to the strip were getting more and more sparse. By the end of the early 2000s, there were tons of clubs and parties at clubs that were definitely borderline queer but open to everyone popping up in South Florida. Overall, they were “cooler” and younger-leaning than the bars in Wilton Manors and the long-running gay clubs on South Beach, so we started going to these mixed spaces a lot more. I didn’t actually end up going to my first lesbian bars until a couple years later on a trip to NYC, where in one weekend, some friends and I went to both the legendary Cubbyhole and to Ginger’s. Those spaces were much different from what I’d experienced back home. People were more radical, more gender exploratory, more punk, more like me and my friends. After that trip, I was jealous that they had a brick and mortar place to go to every weekend, when we had to follow parties and queer nights that bounced from venue to venue every few weeks or didn’t happen at all.

Those parties and queer nights I mentioned are still pretty much a mainstay in South Florida, but New Moon closed in 2014, and many of the remaining gay bars are, as they always have been, basically for men. It’s really tempting and compulsory to look at this as a distinctly South Florida problem, but it isn’t. It’s an everywhere problem.

Before we get to the end though, I think it’s important we take a step back and examine how we got here in the first place. Let’s jump into some dyke history, shall we?

A short history of the American lesbian bar

I think it’s important to situate the development of the lesbian bar within the broader context of American social history. As we all know, cis women have never enjoyed the same freedoms as men, and in the first half of the 20th century especially, there weren’t many places outside of the domestic sphere where women could come together with other women. So, you can imagine the empowerment that comes with being in a space devoid of cis men, which lesbian bars frequently were. Since the inception of the lesbian bar, these spaces have often been more than just a watering hole for queer women. Many lesbian bars throughout the 20th century served as places for women to gather to do community organizing work, to take care of each other, to get healthcare, and to just generally help out the communities where the bars were located. In these spaces, women of all ages were able to come together and build community and camaraderie in a way they couldn’t in any other place. This is not to say that lesbian bars have always been sites of resistance against white supremacist, heteronormative culture, but I do think it’s important to point out that community formation and support was an important part of their function in queer culture and society, even if the members of that community weren’t as revolutionary as we wish they were.

It’s widely accepted that the first lesbian bar to open in the U.S. was Mona’s 440 Club in San Francisco, California in 1936. According to Nan Alamilla Boyd’s book, Wide Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965, Mona Sargeant and her husband, Jimmie, originally established Mona’s as a “bohemian” spot to take advantage of the ending of prohibition and the ever-expanding culture of tourism growing in the San Francisco area. It was mostly open to writers, artists, and sexual “deviants” of any flavor but quickly became well-known for its mostly female staff, clientele, and popular drag king shows after Mona and Jimmie noticed a desire for more clubs of this persuasion in the area. In archival material from Mona’s bar, including ashtrays printed with the logo, Mona’s advertised itself as a place where “Girls could be boys.” Many of the performers at Mona’s were butch women, often performing to a mixed audience of butch and femme women, “straight” women, and gay men. Mona’s clientele was interesting because it was frequented by lesbians and also by supposedly straight women whose husbands were away at war. Many of the performers at Mona’s were butch women, like the legendary Gladys Bentley, often performing to a mixed audience of butch and femme women, “straight” women, and gay men. Mona’s 440 Club stayed open — eventually changing ownership to Ann Dee who changed the name to Ann’s 440 Club — until the late 1950s. And while it’s certainly true that Mona’s broke barriers and influenced the opening of bars like it across the U.S., calling it the “first lesbian bar” is actually somewhat historically inaccurate.

Because the Prohibition of the 1920s drove all bars to go “underground,” there’s a lot of queer bar history that either wasn’t well-documented or is just not very well-known. Mona’s 440 Club might have been the first official lesbian bar, but the first-documented bar-like hang out for lesbians, Eve’s Hangout, actually opened 12 years before Mona’s 440 Club in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. Eve’s Hangout wasn’t technically a bar because it wasn’t allowed to be, but it was established specifically as a “tearoom” for women (of course, it was more specifically for lesbians), immigrant writers and artists, and Jewish people. Eve Addams, a Polish immigrant to the U.S. and the founder and operator of Eve’s Hangout, opened the tearoom at 129 MacDougal Street in 1925. Unlike Mona and Jimmie Sargeant, whose sexualities are unknown and probably heterosexual regardless of the fact that they opened Mona’s 440 Club, Addams was an out and proud lesbian looking to create safe spaces for women like her here in the U.S. Eve’s Hangout frequently “hosted after-hours, locked-doors meetings, where women-loving women could share their experiences without fear of censorship or discrimination.” Supposedly, Eve also hung a sign on the door of the tearoom that said “Men are admitted but not welcome.” It didn’t take long for the Hangout to become one of the most popular spots in the area, drawing the attention of not only queer people but also the local police. Eve’s Hangout was shut down in 1926, and, tragically, Addams’s work at the Hangout and in the community led to her eventual arrest, deportation, and death at Auschwitz in the early 1940s.

Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, more lesbian bars opened in big cities (and some small towns) all over the U.S. Most of these places were male-owned because, unfortunately, women couldn’t be trusted with handling their own money and property until the 1970s. Many of the lesbian bars that opened during this period were owned by male landlords and run by their female tenants. This fact is pretty widely known when it comes to LGBTQ history, but one of the biggest benefactors of the lesbian bar business was the Italian Mafia. Because banks were reluctant and/or completely unwilling to fund women-owned businesses during this time, the Mafia was one of the few places women could go to get loans or to rent property for their businesses. I don’t want anyone to be confused in thinking that the Mafia is some progressive organization. The truth is, they didn’t care what these women were doing as long as they got their kickbacks. But the relationship between the women who ran the bars and the men in these organizations was certainly interesting. Of course, because they were interested in keeping these businesses open, they often paid off police to stop raiding the bars and other members of the community to keep quiet about the bars’ locations. As we know, this didn’t stop raids from occurring but it is so wild to imagine a Tony Soprano type paying off part of the NYPD to keep some place called Kitty’s Hideaway (or something similar) open.

While lesbian bars were often a refuge for queer women (and some men), it doesn’t mean they were safe and welcoming spaces for everyone. Lesbian bars during this period were usually racist and less open to trans people and people of varied gender experience. It’s obviously not as well-documented as it should be but queer Black women, even in places like New York City and San Francisco, mostly weren’t welcome in these spaces and couldn’t be part of the scene. For Black queer women, house parties — which was actually showcased in episode six of A League of Their Own — were the main way they were able to gather and celebrate themselves and each other. In the 1950s, the lesbian bar scene shifted somewhat with more bars being opened for working-class lesbians in big cities, especially. These bars were more racially diverse, but still not free of racism or white supremacist definitions of sex and gender. And although trans people were often part of the gay and lesbian bar scene, they weren’t exactly welcome with the kind of enthusiasm you’d expect. Because of the story of the Stonewall Uprising, people have a tendency to think trans people were embraced as members of the community, when the opposite was usually true. In addition to that, at this time, lesbian culture was, of course, dominated by a binary understanding of sex and gender that was liberatory for some and exclusionary for others. Of course, as culture changed, many lesbian bars became sites that were more welcoming of Black women and women of color and less binarist thinking. But I think it’s important to give a full picture of their evolution into the second half of the 20th century.

By 1980, there were over 200 lesbian bars around the country. 200. That’s actually quite a lot. But as of 2021, the Lesbian Bar Project has recorded that there are only 24 left in the U.S.

What the fuck happened?

Where have all the lesbian bars gone?

There are so many myths about why lesbian bars close and/or don’t survive. So many. There are two that I’ve heard more times than I count. The first is, old reliable, “queer women just don’t party the way queer men do.” When people say this, they say it like it’s a scientifically verifiable fact. I don’t know if “willingness to party” can be measured in any real way, so this just feels like a cop out that people use to hide something much more sinister or difficult to discuss. If we consider the way the society around us works, it makes more sense that being a woman who owns a business that specifically caters to women is extremely difficult. As it is, women already earn less than men, and the more marginalized your identity is, the less you make. This alone puts women at a great disadvantage when it comes to entrepreneurial efforts, but there are also systemic issues that prevent these businesses from staying open or opening at all. From the advent of the lesbian bar, men have had to play some kind of role in their operations, so we can infer what it means when men aren’t involved. Businesses owned by women simply don’t have the same survival rate as businesses owned by men due to a variety of factors, including obtaining bank loans to help keep their businesses afloat when they need it. This means that, since the early 1990s, lesbian bar after lesbian bar has closed its doors for reasons that are structural and completely unrelated to how frequently people show up in these spaces.

Many studies done on this have found just that: a series of structural and systemic issues that have caused the lesbian bar scene to putter out. According to an article in The Story Exchange, one of the biggest factors is money:

“We all know women earn less than men — in 2019, women make $0.79 for every dollar men make — but the disparity can be even more pronounced in lesbian women. Based on a recent study by the UCLA School of Law, LGBTQ-identifying individuals suffer economically across the board with higher rates of unemployment and lower incomes, among other categories. Coupled with the obstacles that women business owners face when it comes to access to capital, it can be difficult for female-owned lesbian bars that rely on female customers to stay afloat. In cities, which tend to be more liberal than, say, rural communities, the demise of the lesbian bar seems counterintuitive. For example, San Francisco has one of the highest LGBTQ percentages in the country, so it would seem that lesbian bars would have an eager and available clientele. The problem, however, is urban gentrification. Techies and creatives, most of whom are well-paid males, have moved in — pushing out a female demographic that doesn’t earn enough or wield enough disposable income to patronize bars.”

In South Florida, we currently don’t have a single lesbian bar across three counties. New Moon has been closed since 2015, and the only other lesbian bar to open in Wilton Manors, named The G Spot (I know, I know), did so about 2 years before the COVID-19 pandemic and then closed as a result of it. Of course, I don’t know the individual stories behind these closures, but I do know about how much the neighborhoods and the cost of real estate have changed down here in the last seven years, and their closures track with the reasons given in the article mentioned above.

As I said, people cite other factors for why lesbian bars have closed down over the years. In an article in the Smithsonian, they discuss that “Lesbian bars have struggled to keep up with rapid societal changes, including greater LGBTQ acceptance, the internet and a more gender-fluid community. With dating apps and online communities, bars aren’t necessary for coming out and connecting with queer women.” And Gwendolyn Stegall states that many queer people “claim that ‘lesbian’ leaves out bisexual women and trans people, who definitely have been historically (or even sometimes currently) shunned from the community.” I definitely don’t disagree that some queer people feel this way. In fact, I think I probably had a bit of a moment thinking this when I was struggling with my gender dysphoria and trying to figure myself out. It’s also very real that there are lesbians out there who are transphobic and heteronormative, which impacts the way spaces are created and patronized. But I don’t think we can say that this is actually a factor in whether or not these businesses survive because although gay bars have faced some similar criticisms, their existence isn’t threatened in the same way, and they don’t suffer the same rate of closure. In fact, if I’m using my neighborhood as a small case study for these phenomena, all of the gay bars made it through Covid, and two new ones even opened up in the midst of it.

To me, it goes straight back to the fact of access to capital. Gay men have a lot more access to capital than lesbians and trans people do as a result of the structure of our society. I don’t think you can untangle that fact from this situation. They have simply always had more money to invest and more money to spend, and it feels like talking about anything else beyond the fact that women and trans people still can’t get what they need is just a distraction.

And I’m not interested in being distracted. The Lesbian Bar Project certainly managed to bring some attention to the issue over the last two years, but similar to how these bars have been disappearing over the years, that attention seems to be fizzling out. I don’t disagree that some of the spaces that have historically catered to lesbians are outdated in terms of their concepts and inclusiveness but I do think there is still a need for places outside of the internet that specifically cater to queer women and trans people. In the last ten years since my friends and I followed queer nights from place to place, my feelings and my life have changed a lot. I don’t go out in the same way I used to, but I still feel that tinge of desire again for a place where I can go often and be with lesbians and queer women and people like me, gender freaks of lesbian experience. Maybe because I’m getting older, I just want to have a place that I can be a regular at and also feel completely at ease. I have a lot of wonderful people in my life, but sometimes, I just want to go out and have a drink surrounded by people who truly, truly get it.

I don’t think it’s a secret that many LGBTQ people feel as if they don’t have a strong network and/or unified community of other queer and trans people in their local areas — I know I feel that way, at least. These spaces have historically been the sites of not only connection and celebration but of resistance and taking power for ourselves. They’ve been places where we can dance all night and then rally together in the morning to fight back against the powers that are trying to destroy us. I often wonder how much different the world would be if we still had these spaces of so many possibilities, these spaces where we could meet friends or make new ones, fuck in the bathrooms, do drugs safely, drink, host writing groups or knitting circles or open mics, listen to live music, have afternoons to engage in resistance studies together, plan radical actions and have the organizing space to act on them, take care of each other in a variety of ways, or just grab a drink after work. I wish we were still willing to fight for these spaces, and I wish we could experience them together as Addams and so many others like her were years ago. We not only deserve them, but we desperately need them.

13 Photos of Dyke Culture Between 1988 and 2003, by Phyllis Christopher

feature image: Phyllis Christopher

In the late ’80s, photographer Phyllis Christopher moved to San Francisco, where she documented protests, queer nightlife, and more. She later became a contributor and photo editor at the lesbian erotica publication On Our Backs, where she worked one-on-one with models who shared their own kinks and curiosities in its pages.

Earlier this year, Christopher published a collection of her black-and-white photos from this era called Dark Room. The book also includes writing from Susie Bright, Laura Guy, and Michelle Tea, as well as an interview with Shar Rednour. In June, I interviewed Christopher about her life and creative process, and she has generously offered to share more of her photography with us.

I love these photos. They feel joyous and hot, and they capture an underground dyke culture that was loud, ferocious, and teeming with sexuality.

If you like what you see and want to see even more, purchase Dark Room online from Book Works. And if you’re near San Francisco, you can attend the San Francisco book launch for Dark Room on Sunday, August 21st, from 3pm to 5pm at the Folsom Street Community Center. Phyllis will be joined by Susie Bright, Laura Guy, Shar Rednour, and Michelle Tea. Carol Queen will host.

San Francisco, CA – 2000 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Karin – Buffalo, NY – 1988 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Queer Nation visibility action at Concord Mall – Concord, CA – 1990 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Dancers – Club G Spot – San Francisco, CA – 1989 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Pro-Choice March – San Francisco, CA – 1989 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Elvis Herselvis at Klubstitute – San Francisco, CA – 1991 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Alley, South of Market – San Francisco, CA – 1997 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Cartoonist Kris Kovick- San Francisco, CA – 1992 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Flannel Fetish Tribute for On Our Backs – San Francisco, CA – 1991 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Daddy’s Boy – San Francisco, CA – 2000 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Michou and Cooper – San Francisco, CA – 1997 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Tribe 8 – San Francisco, CA – 1995 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

San Francisco, CA – 2003 (Photo by Phyllis Christopher)

Which Historical Lesbian Bars Would American Girl Dolls Have Visited?

Let’s just take it as a given that American Girl characters are queer icons. I’m a Molly, if you couldn’t tell, but also with strong Kit tendencies. I’m saving my “American Girl Made Me Gay” essay for another day, but let’s be clear that that’s where I’m coming from.

Thanks to the incredible work of Allison Horrocks and Mary Mahoney at the acclaimed American Girls podcast, I’ve been thinking a lot about how my childhood fascination with the historical American Girl books shaped my lifelong love of history (the early 20th century in particular). In wondering how these stories shaped the person I’ve become, I’ve also become curious about how the characters I love might have grown up. These stories, for me, are so closely connected to their chronological settings; Molly is the 1940s girl, Kit is the 1930s girl, etc, and imagining them older, in subsequent decades, lets these vibrant characters expand beyond their original narrative confines.

So let’s imagine these adorable queer icons as they’d be turning 18, maybe figuring things out, maybe beginning to search for queer community. What community spaces would have been available to them as they entered adulthood? What bars would they be sneaking into? What might their queer lives have been like?

Samantha Parkington — born 1895, turns 18 in 1913

Because Samantha’s original books are set in 1904, I’m counting her as my first 20th century girl, and what a helluva start to the century she represents. A lot of Samantha nostalgia centers her luxurious accessories, but beneath all the frills, Samantha is the badass femme queen we all deserve. Growing up with her bicycling suffragette Aunt Cornelia, how could Samantha become anything other than a legend? Her civic-minded progressive labor politics are central to her story and I can see her growing up to do further community outreach and advocacy work, probably as one of those SpinstersTM who totally had a “historians will say they were friends” kind of partnership. As historian Lillian Faderman notes, at this point in time there weren’t many bars where women could go; Samantha would more likely have found her queer family at a ladies’ club or activist circle. However, by her mid-to-late twenties, I know in my heart Samantha would’ve been sneaking off to speakeasies with her, ahem, ~best friend~ Nellie and reading Radclyffe Hall.

Rebecca — born 1905, turns 18 in 1923

Rebecca wasn’t yet part of the story when I was a kid, but god I wish I’d had these books when I was in the thick of my A Tree Grows in Brooklyn phase. Rebecca grew up in New York during peak Edith-Wharton era, and would be 18 just as the 20s were really starting to roar. Prohibition was in effect from 1920-1933, but let’s be real: this girl’s too resourceful not to find the best house parties and speakeasies. By the early 1920s, bars in the West Village were growing devoted gay clientele, like one which in 1929 would be renamed Marie’s Crisis (and which remains a beloved gay piano bar.) However, I like to imagine Rebecca in community with Eve Adams, subject of a superb recent biography by queer historian Jonathan Ned Katz. Eve Adams was a Jewish immigrant from Poland who traveled around America distributing radical leftist literature, and whose 1925 book Lesbian Love was burned for being ~indecent~. Additionally, Eve Adams opened a salon and tearoom in Greenwich Village called Eve’s Hangout where queer community congregated — I picture Rebecca here, probably with a copy of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein.

Kit Kittredge — born 1923, turns 18 in 1941

Oh Kit, rough-n-tumble butch queen of my heart. Typing up her own newspaper on a clattery typewriter, building a scooter out of fruit crates, playing baseball, and dressing as a boy to ride the rails and learn firsthand about Depression-era “hobo” culture, it’s safe to say we know that Kit grew up to be a badass. She’d be coming of age in wartime Cincinnati, when military necessity led to the town’s industrial boom. As a center of manufacturing, Kit would’ve had no trouble finding a job — can’t you picture her, Rosie-the-Riveter-style, slinging heavy machinery around and looking very at home in her shop floor coveralls? Especially during the war, working-class lesbians congregated at dive-ier bars, often close to the plants for an after-shift drink; this is the generation who would’ve been the elders in Stone Butch Blues. These bars haven’t received the level of historical preservation I think they deserve; since they so seldom advertised themselves as the de facto queer community centers they were, it’s hard to name for certain any specific institutions Kit might have frequented. However, Cincinnati’s current vibrant LGBTQ+ community from the 60s onward didn’t come from nothing. We know there must’ve been somewhere for Kit to get a drink and cruise for crushes after a long shift. By the time of Cincinnati’s first pride parade in 1973, Kit would have been 50 years old — a beloved butch elder, I imagine, at the front of the parade.

Nanea Mitchell — born 1932, turns 18 in 1950

Nanea is Hawaiian, living in Honolulu during the Pearl Harbor attacks. I want to shout out here how great it is to see another indigenous character added to the lineup, and with such rich and attentive historical specificity. Nanea witnesses the attack directly herself; a large part of her plotline is about recovering from this trauma and from the ensuing separation from her best friend Lily, whose family is forced to the mainland by the enforcement of Japanese internment. Even against this harrowing backdrop, wartime Honolulu was a fascinating place — acclaimed female pilot Cornelia Fort was stationed there, teaching men how to fly, when she witnessed the Pearl Harbor attack from the air, and you better believe that those fantastic, fierce lady pilots were, ahem, yknow. Nanea herself is a creative, headstrong, often-impulsive girl with a penchant for Nancy Drew novels. (Did Nancy Drew make me gay? Probably not, but having a hot girl sidekick named George sure didn’t hurt the cause.) By the 1950s, I don’t doubt that teenage Nanea wouldn’t be having any trouble shaking up gay adventures. Especially in proximity to military bases like the ones in Honolulu, gay and lesbian bars had sprung up like clover; you can read all about them in Coming Out Under Fire, about how wildly gay the WWII-era forces were, and where some of the interviews were even contributed by lesbian former-WACs still living in Honolulu.

Molly McIntire — born 1934, turns 18 in 1952

Molly’s stories are set in Jefferson, Illinois, which I take to mean Jefferson Township outside of Chicago; heading into the city, then, as an 18 year old, Molly would be walking into the thick of McCarthy-era vice raids and mob-controlled underground bars. (If you thought Molly would grow up into some straitlaced boomer, think again.) The Andersonville area of Chicago remains to this day a queer haven, but back in Molly’s day the scene looked rather different. This extensive entry in the Chicago Encyclopedia and this piece from the Chicago Tribune outline the context of the community Molly would’ve encountered, including the vibrant community led by Black LGBTQ+ people that coalesced on the South Side and included popular and long-standing mixed-race drag balls which lasted well into the 1950s. In addition to these gatherings, Molly’s main South Side bars would have probably been places like Mommy-O’s (what a name!) and The Fiesta, where she would’ve risked police surveillance or harassment, particularly if she butched it up beyond the law’s unofficial rule that people had to be wearing at least 3 items of clothing designated for their assigned sex. (May they roll in their graves at the sight of us now!). Nowadays, there are tours available of Chicago gay neighborhood history, and these interviews with patrons of Chicago’s lost lesbian bars give us a glimpse into the scene as it would’ve developed after Molly’s coming-of-age.

Maryellen Larkin — born 1945, turns 18 in 1963

Maryellen is a more recent addition to the Historical Characters line, and I love her whole vibe. She’s a polio survivor, adventurous and creative and headstrong, and she works in her family’s seaside diner in Daytona Beach, Florida. This girl is a bartender in the making if ever I’ve seen one, complete with opinions about what goes on the jukebox! Over at Dishing with Mark and Carrie, local legends in the queer community have also compiled an informal, unverified, entirely delightful rundown of Florida Bars That Were. Most of these bars catered primarily to gay men, but they speak to a lively and long-standing queer community in Central Florida. About an hour away from Maryellen in Orlando, she’dve had options like those compiled here by the Florida LGBTQ+ Museum, including Palace, which opened in 1969 and later became home to Face to Face, aka Faces, the first bar for LGBTQ+ women identified in Central Florida. Maryellen might even have been around the same age as the belovedly eccentric mother in Kristen Arnett’s Gay Florida Masterpiece Mostly Dead Things, no? I bet we’d see some gay taxidermy at her bar.

Melody Ellison — born 1954, turns 18 in 1972

God, I wish Melody had been around when I was a kid! This is a girl raised on Motown, coming up in Detroit during its industrial boom, and already (look at that Mary Tyler Moore style outfit!) a pop culture icon. Where was Melody when I was making my dad blast Motown classics radio on the way to school? She and I love the same artists — Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, Marvin Gaye, and the like — and Motown was much like Hollywood in its draconian enforcement of straight femininity in its artist contracts despite the popularity of bands like The Supremes with openly queer fans. You can find out more about the queer Motown milieu in the delicious mystery novels by Cheryl Head, which feature a queer Black private investigator! By the 70s, however, white artists closely connected with the Motown crew like Dusty Springfield were publicly out, and the rise of disco was creating an environment more openly welcoming for queer artists of color. Black lesbian organizing was gaining momentum as well; while the Black Lesbian Caucus was based primarily in New York, their newsletters had national circulation, and groups like the Salsa Soul Sisters offered Black and Latinx women an alternative to often-racist and otherwise discriminatory bar spaces — groups and networks like these are where Melody might’ve gotten her best recommendations! Over at this interactive map, you can watch the expansion (and, sadly, contraction) of the Detroit gay bar scene, based on data assembled by historian Dr. Tim Retzloff.

Julie Albright — born 1966, turns 18 in 1984

Oh, this sweet little long-hair-butch San Francisco sports gay. By the time Julie would’ve been coming out, the scene documented in historian Nan Alamilla Boyd’s iconic book Wide Open Town would have been a thing of the past and San Francisco’s icon Mona’s (440 Broadway, ‘Where Girls Will Be Boys’) which is often credited as the first openly lesbian bar in America would have been closed for a while. We can’t forget that the mid-eighties would’ve been right as the AIDS crisis accelerated, and a team player like Julie wouldn’t have been able to escape the urgency of this moment. However, in addition to community organizing, and queer women’s volunteer efforts to support HIV and AIDS patients, I like to imagine her in such options as Amelia’s, Wild Side West, and the iconic Maud’s, subject of the magnificent and profound documentary Last Call at Maud’s that you can stream for free online via your local library. Personally, I’m betting that Julie would’ve been fielding Maud’s softball and basketball teams, and driving the girls to the bar after practice in her beat-up van. She strikes me as a cold beer kind of gal.

Courtney — born 1976, turns 18 in 1994

So, like, we know they made Courtney her own doll-sized American Girl doll (Courtney’s a Molly; same, girl, same) — are they going to make Courtney little doll-sized copies of Dykes to Watch Out For too? Courtney grew up in Southern California in the 80s, and by the mid-90s I bet she’d have found her way to Los Angeles, which for a time was an unofficial capital of lesbian bars. The longest-running appears to be The Palms in West Hollywood (which operated from the 60s until its closure in 2013), and many more from that neighborhood are represented in the holdings of the local June Mazer Lesbian Archives, where oral histories have helped patch together this history of earlier bars in the area dating back to the 1950s. Latinx and Black lesbians, however, congregated in East LA, where bars like Kitty’s are immortalized by the ONE Archive LGBTQ+ Research fellows. The number of such bars over all of LA has plummeted, sadly; this 2019 article by a local queer paper and this one from the following year highlight the erosion brought on by gentrification and other forces.

I’m just getting started — queer history didn’t begin in the 20th century, and the 18th and 19th century American Girl characters deserve their queer lives imagined too. Keep your eyes peeled for Part 2 featuring beloved characters Kaya, Felicity, Caroline, Josefina, Kirsten, and Addy!

In the meantime, if you’d like more information about the past, present, and future of LGBTQ+ bars and community spaces, I recommend searching out a secondhand copy of the Our Happy Hours anthology, edited by LGBTQ+ literary legend Lee Lynch in the aftermath of the Pulse Shooting, for its firsthand accounts. More wonderful anecdotes can be found in this VICE documentary done by JD Samson, and in the recent Lesbian Bar Project committed to supporting and promoting the remaining bars across the country. If you’ve got any historical insights or modern-day recommendations for queer bars and community spaces worth supporting, lemme know all about what I’m missing out on in the comments!

Meet The Owners of Herz, a Lesbian-Owned Bar in Alabama

There are currently twenty-one lesbian-owned bars in the United States in 2021, down from nearly 200 that existed in the late 80s. A decline of this stature was unsettling and dumbfounding. Had we digressed in some capacity? Was this some conservative-won plight to eliminate our spaces?

When I first learned this fact from my friend Byrdie O’Connor, the producer of the Lesbian Bar Project, there was an unspoken, I know. Can you believe it? between us. I immediately assumed that the majority of the remaining lesbian-owned bars were in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, minus A League of Her Own in Washington D.C.. But Brydie shook her head. Only three in New York (Henrietta Hudson, Cubbyhole and Ginger’s), one in San Francisco (Wildside West), none in Los Angeles.

Where are the rest? They’re splattered all over the country, from the Midwest to the South, including a bar called Herz in Mobile, Alabama.

Hearing about Herz sparked a specific curiosity in me. I wanted to know what was keeping it alive, so I got in touch with the women behind the Lesbian Bar Project, and with the owners of Herz.

photo by Brydie O’Connor

“It’s a multi-faceted issue, of course. But one of the main reasons has to be gentrification. I think it’s less of an issue in the Midwest and parts of the South,” said Erica Rose, one of the Lesbian Bar Project’s directors. “Gentrification wipes out marginalized communities. There’s a major wealth gap, and a lot [of LBTQ business owners] just can’t keep up with the rising rent in gentrified cities.” A pay gap still exists between women and men, a fact that increases for LGBTQ+ individuals. Thus, our opportunities to open and maintain businesses are not always plentiful, gentrification aside. LGBTQ+ clientele bases are also smaller than their cis-heterosexual counterparts, making it that much more difficult to make ends meet depending on the queer population size. Rising rents, both residential and retail, often end with the ostracization and removal of marginalized housing opportunities and businesses. While New York City houses one of the largest populations of LGBTQ+ people in the United States, it’s also one of the most gentrified cities in the country. It makes sense that only three of the estimated 25,000 bar and nightlife establishments in New York City are lesbian-owned and centered. New York City follows San Francisco and precedes Los Angeles on the list of most gentrified cities, two of the other most LGBTQ+ inhabited cities in the U.S.; the former houses one lesbian-owned bar, and the latter has none. When marginalized communities are pushed out of cities, or forced into financial struggle to remain there, their businesses suffer or cease to exist. The communities they serve also suffer.

The owners of Herz, Rachel and Sheila Smallman, are originally from Mississippi but traveled around different cities in the South to find the perfect location to open a lesbian bar. “We were thrown out of a gay bar in New Orleans,” Rachel Smallman said. “For being women. We were shocked and hurt, but it also helped solidify what we already knew, that we had to open a bar ourselves.”

contributed by Lesbian Bar Project

contributed by Lesbian Bar Project

Established in 2019, Herz’s building once held a straight dive bar. Between a perfectly vacant building, a dream and a loan, the Smallmans opened Herz, the only inclusive, lesbian-centered and owned bar in the state. Because it’s still in its infancy, it’s hard to determine how the bar will fare against gentrification, especially as it’s located in the 80%-white neighborhood of Skyland Park. However, gentrification remains an issue in cities most prone to significant population, job, and economic growth. Mobile’s population has been on a steady decline the last few decades, and its median income is around $25,000.

But a lack of full-gentrification aside, Mobile still struck me as a particularly unusual city to house one of the last lesbian-owned bars. Alabama has been coined one of the worst states for LGBTQ+ people due to its discriminatory laws and practices. Its recent anti-trans bills are nothing short of targeted and violent, and the state has been cited for numerous LGBTQ+ marriage license denials. “[Herz is] dedicated to inclusivity,” Rachel said. “It’s something that deeply matters to us. These trans children, so many of them are homeless, so many of them don’t have safety. We want to provide that space.”

Herz is not just providing a safe space for patrons; it’s actively seeking to uplift and further the voices and missions of LGBTQ+ activists, so that conditions for LGBTQ+ Alabamians improve. Kimberly McKeand is an out LGBTQ+ woman running for City Council in District 2 of Mobile. Signs toting her campaign slogan, Out for McKeand, were all over Herz earlier this year when the bar hosted a political event for her.

“It’s different, the thought process of people around here,” said Rachel Smallman. “I’m from Mississippi, but it’s different in Alabama. They thought [Herz] was a strip club, and then they found out it was a lesbian bar owned by two Black women. They weren’t ready for us.”

The difficulty inherent in two Black lesbians owning a business for LGBTQ+ people certainly played a role in Rachel and Sheila being the first to make such a move in Alabama. Though, with 21 known lesbian-owned bars left in the United States, the reasons why there aren’t more of these spaces are clearly evident beyond Alabama’s borders.

“I think, as women, we’ve been told for so long what we are and are not capable of, and what we can and cannot accomplish,” Rachel said. “It’s harder to take chances, but once you do, you realize what’s possible.”

There’s an estimated 400 to 1,000 bars in the United States that cater to gay men; three of them are in Mobile, Alabama. The overall economic achievement of cis gay men, a product of a patriarchal system even when considering sexuality-based societal oppression, has allowed them to own and operate businesses at a higher rate. And even as gender roles are challenged and dismantled, women’s same-sex partnerships are more than twice as likely to involve raising children, a fact that could certainly affect not only bar ownership, but patronage. Regardless of marriage, parenting, or access to funds, however, women have been taught for millennia that their goals, aspirations, and dreams should be small, reasonable, family-based or minimal; LBTQ women and nonbinary individuals often have these same roles forced upon them, amidst trying to battle cis-heteronormativity. Dismantling these notions can be a constant struggle, one that would impede not only odds, but desires, to open up a bar catering to the LGBTQ+ community.

“With the passing of gay marriage and more widespread tolerance – I won’t say acceptance – we’ve had some general assimilation,” Rose said. “And it’s great that the assimilation has provided us with safety, but along with it, we erase what makes queer spaces so comfortable and safe. Straight bars are still not catered specifically to [our community]. If we lose our bars, heteronormative culture prevails.” Rose’s comments touch on something integral to the conversation: Our elders tirelessly fought for our ability to move around the world with a sense of safety. Within that, though, the necessity for queer-centered spaces has diminished. That is not to say the desire has diminished, though. “Before we opened Herz, I had never been to a lesbian-centered bar,” Rachel said. “It’s so different, and we need more spaces like it. We deserve to have a place where we’re at the forefront.”

While I understood a bit more about why Herz was opened, I still wanted to know: what’s keeping Herz open?

contributed by Lesbian Bar Project

“Community,” Rachel said. Even though the Smallmans were certain about the necessity and their desire in opening an inclusive, lesbian bar, they were still pleasantly surprised by their growing number of customers. “We had no idea how needed it was until we did it,” Rachel said. Herz quickly became the spot to go, a place holding an energy of acceptance, celebration, and joy that’s almost palpable. Starting at 4pm, Herz’s patrons nearly float through the door for after-work drinks, dates, birthday parties, celebrations, and political speeches.

The LGBTQ+ community has a distinct way of showing up. We’ve been deprived of safety, so we provide it. We’ve been denied space, so we create it. We’ve been cast out, so we open our arms. Quickly, a bar can provide the familial love some of us need and all of us deserve.

“Herz is made special by the people who come here. A lot of us don’t have family,” Rachel said. “But when you’re here, you’re family. We make certain of it. We’re built on it.”

The Lesbian Bar Project Raises Over $100,000 to Protect 15 of Our Last Lesbian Bars

“I remember a space I never knew existed,” says comedian, actor and butch lesbian icon Lea DeLaria (“Orange is the New Black”). “A space rooted in love, and history.”

Her narration plays over a ninety-second public service announcement made up of both archival photos and videos, and recent footage, released last month by a campaign called the Lesbian Bar Project. Neon lights dance across the grinning faces of bar patrons through the decades as they embrace one another, and themselves, in rooms and streets so full of joy that it’s palpable even through the screen.

“I remember the lost spaces,” says DeLaria, as the PSA pays tribute to the scores of lesbian bars that have been shuttered over the years—places like The Palms in West Hollywood, Lexington Club in San Francisco, and Kooky’s, Bonnie & Clyde, Ariel, and too many others in New York City to name.

Since the 1980s, the number of lesbian bars across the United States has been in decline. At one point there were an estimated 200 nationwide, but bars catering to women, and those for queer people of color, are closing at rates up to 20% higher than even other gay bars. At the start of 2020, there were just sixteen lesbian bars left —and in a circumstance becoming increasingly familiar to small business owners across the country, one has already been forced by pandemic-related financial strain to close its doors.

Lesbian nightlife always has been, and always will be, tenacious and ever-evolving. Many themed parties have sprung up in recent years, more versatile and flexible than bars, and dazzling in their own right. Nonetheless, the absence of more permanent spaces, and the history they hold, is deeply felt.

One such space is the Stud, San Francisco’s oldest gay bar. The Stud was founded in 1966 and was known not only for its vibrant atmosphere and iconic drag nights, but also for the enduring community it has been home to. Over the decades, including during the White Night Riots of 1979, and throughout the AIDS epidemic, people have gathered on the sticky floor of the Stud to party, to grieve, and to organize.

The Stud has changed hands and locations more than once, and when rising rent made its future uncertain in 2016, a collective of LGBTQ artists and performers came forward to rescue the space and form the first nightclub co-op in the country. This June, however, with lockdown dragging on and the building expenses mounting, the collective was forced to announce the club’s closing. The Stud had a proper 2020 send-off, in the form of a virtual drag show, and the collective has already begun searching for a new venue. For the time being, though, the Stud is yet another queer space relegated to history.

The Lesbian Bar Project is hoping to deliver the bars that still remain from a similar fate. The group’s public service announcement, co-directed by filmmakers Erica Rose and Elina Street, is part of phase one in their plan to preserve the sapphic splendor of lesbian bars for future generations.

For their purposes, the Lesbian Bar projects defines a lesbian bar as one that prioritizes “creating space for people of marginalized genders; including women, non-binary folks, and trans men,” a mission that’s as inclusive of modern crowds as it is true to the storied history of lesbian bars and those who have frequented them. Over the years, these spaces have been havens of acceptance and community, in particular when compared with the at times overwhelming whiteness and cisness of bars more geared toward a clientele of gay men.

They have also served as hubs of political organization. In this vein, the group’s PSA seeks to remind viewers of the spirit of activism and protest that is intrinsic to the lesbian community, and the LGBTQ community as a whole. “I remember that pride began as a riot,” says DeLaria, and protest footage rolls, including a clip from this past summer’s 15,000-strong Black Trans Lives Matter rally in Brooklyn, NY.

“Losing just one more of these cherished spaces has devastating consequences for queer people in this country,” says Rose.

As Street describes, the goal of the project is to not only highlight the bars and “cherish the memories of the lost spaces,” but to, “project a future of hope and sustainability within our community.”

In the United States, most small businesses are owned by men—bars, even more so. There’s something lovely and right about Rose and Street, two queer women in the traditionally male-dominated industry of filmmaking, working to bolster these equally rare spaces.

The project’s fundraising website launched on October 28th, in conjunction with Jägermeister as part of their #SaveTheNight initiative to support nightlife through the pandemic, and non-profit arts service organization Fractured Atlas. The project is produced by Lily Ali-Oshatz and Charles Hayes IV, and executive produced by DeLaria, and The Katz Company.

The Lesbian Bar Project, striving to preserve many facets of queer life, also hosted virtual events throughout the month-long fundraising campaign. These included a roundtable discussion, in partnership with Rockland County Pride Center, featuring Roxane Gay and Rosie O’Donnell alongside narrator DeLaria; and a virtual version of the comedy show and podcast Dyking Out, which included Leo Sheng, Sydnee Washington, Ali Clayton, Emma Willmann, Cameron Esposito, Rita Brent, and Mary Lambert.

And there’s more in store. Those gearing up for the dark, socially-isolated binge-watching season ahead will be glad to hear that the next phase of the project, currently under production, involves plans for an episodic docuseries seeking to explore the history and cultural significance of lesbian bars in the United States. Rose said of the project, “I want to use the power of filmmaking to illuminate the rich history…and provide an opportunity for Lesbian Bars to tell their stories.”

And if you’re eager to learn more about the rich present of the 15 venues still open, the Lesbian Bar Project website includes further information about each of the remaining lesbian bars, including a map that shows them scattered across the country like sparse beacons, and photos and statements from their owners.

Rose and Street, both in New York, are longtime supporters of their own local lesbian bar, Cubbyhole. “I like to say that Cubbyhole knew I was gay before I did,” says Rose.

Lisa Menichino, owner of Cubbyhole, shares that, “3/16/2020, due to the pandemic, was the first time we closed in 27 years. We cannot allow ourselves to become an invisible minority,” Menchino goes on. “We must continue to have a presence. We have to find a way to survive.”

Between October 28th and November 25th, the Lesbian Bar Project raised $117,504.50 toward that goal of survival.

“We are elated, and the amount raised definitely exceeded our expectations,” say Rose and Street. “The goal was not only to raise money and give immediate financial support, but to garner visibility for these vital institutions that are disappearing at a staggering rate.”

And in keeping with the proud tradition of dyke nightlife, the bars are already rising to the occasion. “Lisa Cannistraci of Henrietta Hudson is reimagining her space and turning it into what she calls a ‘European Café’ experience,” shared Rose and Street. “Many are galvanizing the support received from the campaign to do their own virtual events, like Jo McDaniel of A League of Her Own D.C. who plans to host conversations with local queer activists and artists as part of an on-going series.”

The great thing about virtual events? You can attend them from anywhere. It’s impressive, but not at all surprising when you consider the history these bars come from. With the funds raised by the project, the bars will be able to not only maintain, but expand the communities that depend upon them, and give them their core. As Rose and Street put it, “The women behind these bars are hustlers and innovators.”

Dykes Rule the Night

‘Strictly no unaccompanied men. A lesbian venue for ladies and their guests,’ reads the sign outside She Soho, the only lesbian bar in London. It’s unusual for a queer space to have a door policy like this. It sounds slightly archaic – ‘Ladies bar, serving men only when they are accompanied by a female escort,’ read the sign on one of New York’s first lesbian bars Café des Beaux Arts, which opened in 1913. This explicit gendering on the door makes the prospect of entry for non-binary, gender-nonconforming, trans men, and trans women less appealing. Though in actuality the space is open to all queer identities, including trans men, and of course sees trans women as women; the prospect of gender judgement, makes She Soho sound like the antithesis of a queer bar.

Having worked on the door at She Soho, which is on Old Compton Street, a bar strip in central London filled with blurry-eyed drunks staggering between bars and kebab shops – it took no time to get it. As tipsy guys repeatedly tried to come in because they “love women,” I had to turn around to double-check that the door sign didn’t in fact say, ‘a room full of available women, please join us.’ Though of course, they’d be mightily disappointed if they ever did get inside, it’s the enigma of the restricted space. “I honestly don’t know what they think they’re going to find down there: lesbian oil baths?” one of She Soho’s managers, Tina Ledger said. Alongside this, groups of women nudged each other towards the bar, as if they’re high school kids and being a ‘lezzer’ is an insult, and guys frantically elbowed their girlfriend’s attention to the venue, as if they’re Indiana Jones and they’ve finally found the lost kingdom of potential threesomes. In a location like this – loaded with lit and horny binge-drinkers – She’s door people have to morph into gender police to preserve the space. This inevitably puts some queer people off.

![]()

She Soho aside, there’s fairly unanimous thinking in British & American dyke bar communities that lesbian bars are queer bars owned by women. If they are not owned by women, as is the case with London’s She Soho and Washington D.C.’s A League of Her Own (both are owned by gay guys who simultaneously run gay bars in the area), then all the managers are lesbians and the venue explicitly prioritises queer women. Gary Henshaw, who owns She Soho and gay bar KU, “really sees the importance of a women’s venue,” manager Tina told me, “he completely respects our door policy and our decision making – he never comes here, and staff wonder why – it is literally just because he respects our door policy so much.”

For 32 years Babe’s of Carytown, a cavernous lesbian bar (they literally have a full-size volleyball court out back) in Richmond, Virginia, has been serving the state’s queer community. “We’re a lesbian bar, a lesbian-owned bar,” said Diana, who’s been working at Babe’s since it opened. “Just over the years, it’s become everyone’s bar. It’s kinda cool in today’s world to have everybody here, in one place, getting along. It seems like there’s so much strife on the streets, at least in here you’ve got boys, girls, gays, straights, Blacks, whites, who what who whatever, can come in, have a good time and be themselves,” she said.

Meanwhile, at 23-year-old My Sister’s Room in Atlanta, Georgia, on a cold Sunday evening in November, a family ate chicken wings while bopping to Kanye West’s “Gold Digger”; a group of college lesbians lined up on their knees to receive poured glugs of Rumple-Minze; a leather power dyke couple sipped IPAs on an intimate date; and a group of gender-queer folks in leopard print watched a raucous drag show.

Similar scenes of community integration can be found at lesbian bars Cubbyhole, Ginger’s and Henrietta Hudson in New York, A League of Her Own in Washington D.C., Lipstick Lounge in Nashville, Gossip Grill in San Diego and Wildrose in San Diego. I spoke with Lila Thirkield, who ran San Francisco’s lauded lesbian haunt Lexington Club for eighteen years until it closed in 2015 about the distinction between a lesbian and a queer bar. “At the Lexington Club, our tagline used to be, ‘your friendly neighbourhood dyke bar,’ but we actually changed it to your ‘friendly neighbourhood queer bar,’ five to ten years before it closed. So was the Lexington club a queer bar?” Lila said, schooling me gently. “Yeah, it was, with a lesbian core,” I said. “So what really, identity-wise, is the difference? We had trans guys working at The Lex; I’m extremely in-between in my gender identity and I owned it. It was hella queer women but there were a lot of trans folks, gay men hung out; I don’t understand what the difference is,” she said.

![]()

The person pouring your drinks, the people on the door, those on a date, congregating in groups, fecklessly making out in the corner and ultimately making money from the space, will tend to be queer women, but there’ll be joined by a whole host of LGBTQIA+ folks and allies, all guests of the lesbian community. Lesbian bars in 2019 are generally emphatic about their ‘queer’ branding. ‘A bar for humans,’ is the tagline of Nashville’s Lipstick Lounge; My Sister’s Room in Atlanta dubs itself “the longest running lesbian-queer bar in America’s south-east”. In Seattle, Wildrose is “a place for women… and all are welcome.” This is partially a desire to be realistic about queer identities. Lesbian bar owners have some of the most uncomplicated opinions on lesbianism, queerness and gender I’ve come across. Through years in queer spaces they know the transience of their own, their community’s and their staff’s identities. Their bars were always intended to be community spaces; offering safety, sanctuary and reasonably priced beer to anyone who might need it. On top of this, there’s an economic need to expand their potential customer base; lesbians are a very small minority, catering to zero-point of the population is an immensely difficult business model to sustain.

Scrolling through gay and queer bars in London, there is no mention, on any of their websites of ‘everybody’ or ‘open;’ active inclusion isn’t something they need to impress. Why lesbian bars need to go that extra mile to assert their queerness is anyone’s guess. The fact that gay men, generally speaking, earn more, drink more and spend more than women, means they are able to fill their spaces without expanding their customer base. The idea that lesbians don’t go out and like to U-Haul – a notion that doesn’t apply to the majority of dykes I know, be they 21 or 61 years old. Similarly, the rise of Tinder, Lex, Bumble and Hinge; writing a quippy bio has surpassed giving the eye across a bar. Or maybe it’s an awareness amongst conscious allies of the dwindling number of lesbian bars worldwide, making them reluctant to take up space in a venue not designed for them.

Despite the very queer and laissez-faire attitude of most lesbian bar owners, there’s also still an assumption that lesbian spaces are more weighted, binary and thorny than gay bars. There are perceptions of ‘the lesbian bar’ as a more restricted or exclusive space, memories of separatist movements in the US in the 70s and 80s, and unfortunate assumptions of TERFiness. I’ve had to convince non-binary mates of mine to come and see how queer most lesbian bars are. I’ve got an “oh fun” from straight friends when I’ve offered a night of karaoke at a gay or queer bar, and an “are you sure?” or “am I allowed?” at lesbian bars. Gay bars are assumed to be open to all – though if we’re honest, lots are undeniably (and unapologetically) dominated by gay men – while a lesbian bar is regarded as reserved, separate, less good and, if I were to get a bit Simone de Beauvoir on it, Other. These are lingering sentiments about lesbian bars that, no matter how firmly the words ‘everybody’ or ‘queer’ are articulated, prove difficult to shake.

When I asked Christa, who bought the Lipstick Lounge in Nashville, Tennessee 17 years ago, if she was aware of any other lesbian bars or bar owners in Nashville, she said she didn’t know of any, and then pointed out that, “the thing with lesbian bars, lesbian-owned bars, once you put that ‘lesbian’ label on there, it’s unfortunate but it’s the reality, how many lesbian bars are open right now?,” she asked.

Not many, is the answer. Of the 1357 LGBTQ bars in the world in 2017, only 36 were lesbian bars, down from 56 in 2014, according to gay-friendly travel guide Damron. There are even fewer now. Lesbian travel bloggers, Dopes on the Road, counted 33 in May this year, in the few months since then, two of these (Pink Hole in South Korea and Shela Tomboy’s Club in Thailand) are now red-flagged as ‘Permanently closed’ on Google.

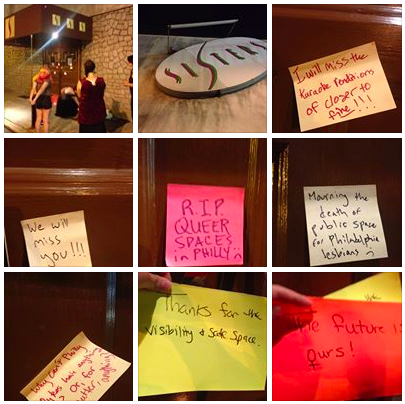

As has been widely reported, lots of the most iconic, long-established and superbly-named lesbian institutions of the last few decades have closed, often for financial reasons; community dyke bars are rarely able to withstand gentrification’s guillotine. New York’s Clit Club closed in 2002, Athens’ Fairy Tale went in 2005, New Orleans’s Rubyfruit Jungle peaced out in 2012, Sisters in Philadelphia left us in 2013, Phase 1 in Washington D.C. was 2016, La Moza in Bogotá, 2018.

![]()

“If I could have kept it open forever, I would have,” said The Lex’s Lila. The bar closed in 2015 thanks to a “landlord who totally screwed me over, and a lot of displacement that was happening in the city,” she said. When she first announced The Lex’s closure – news that shattered San Francisco’s queer community; people wept, others got tattoos of the bar’s entry stamp, many are still in mourning – Lila posted on Facebook: ‘We tried new concepts, different ways of doing things, but we were struggling. When a business caters to about 5% of the population, it has tremendous impact when 1% of them leave. When 3% or 4% of them can no longer afford to live in the neighborhood, or the City, it makes the business model unsustainable.’ Lila, like lots of the queer community who lived in San Francisco in the 1990s, was gradually priced out of the area, moving to Oakland or further afield.

Meanwhile in London, Elaine McKenzie, owned Glass Bar, a stand-alone Grade-II listed beaut of a lesbian hangout in central London, for thirteen years, until it closed in 2008. “The landlord tripled the rent and back-dated it,” Elaine told me over a pint in the hetero-pub that stands in Glass Bar’s shell. “They were redeveloping the area, they didn’t want my sort here, what they wanted was what you have now,” she said, surveying the venue, “a blank, generic outlet that is open to all, they didn’t want something that was exclusive, didn’t see the value or need to have something that promotes women’s needs, somewhere that is a safe space.” The need to capitalise on space, and acquire the highest profits from the most number of people led to Elaine’s brick-and-mortar departure from central London. If lesbian bars, for the most part, are queer bars run by women, this makes them a very interesting case study. While they are imagined to be of niche gay interest, they are in fact a model for women-owned small businesses – though the conversation is rarely framed like this.

“How many even female bar owners are there?,” Lila asked pointedly. Online there’s evidence of women making waves in the hospitality industry but bar owners are often sprinkled in with bartenders, supervisors and managers presumably because there simply aren’t enough women behind the spaces. “We need to have the conversation around what it’s like for women to be the owners of spaces and have the capital, mentorship, ability and training in the way that our society is set up,” said Lila. It is now as it was hundreds of years ago, wealthy men own the land; wealthy men decide what businesses operate on their land; wealthy men choose other wealthy men to make the businesses function as they should. Community-minded lesbians are quite far removed from this equation.