What Really Happened With The Gap Lesbian Avengers Pride T-Shirt

Almost one month ago, the queer internet exploded when it seemed that the Gap had stolen art from a lesbian activist for a Pride t-shirt campaign. On May 19, I saw a tweet by @rachelcorbman about one of the Gap’s “Pride T-Shirts” which featured the iconic logo of the Lesbian Avengers, a direct action group started in 1992.

https://twitter.com/rachelcorbman/status/1395148408860680192?s=20

Predictably, Queer Twitter was horrified. On May 20, @roxsamer posted a photoshopped image, correctly attributing the original design to Lesbian Avenger Carrie Moyer and linking people to the Lesbian Avenger’s website, suggesting that folks should learn more about the activist group and not support a corporation such as the Gap.

The Su Friedrich edit 🔥Learn about lesbian art and activist history. Fuck the Gap. https://t.co/LRHo8oaShX pic.twitter.com/urneBbtgsW

— Cat Dad, Ph.D. (@sadcatdadd) May 20, 2021

Finally, also on May 20, INTO published a piece titled Did the Gap Steal a Lesbian Artist’s Design and Put It on a Pride Shirt? which incorrectly reported the original design was created by lesbian artist Carolina Kroon (it was created by Carrie Moyer, who is correctly credited in the graphic tweeted above) and concluded: “So far, the Gap hasn’t responded to the accusations.”

But the answer to the question is no. The Gap did not steal lesbian artist Carrie Moyer’s design and put it on a Pride shirt… because Carrie sold it to them.

On June 1, I sat down to chat with Carrie Moyer and Maxine Wolfe, two of the founders of the Lesbian Avengers, over Zoom. We connected through a mutual friend who had told me they were interested in explaining what had really transpired.

Carrie explained that back in 2019, Avram Finkelstein reached out to her to see if she’d be interested in talking to an art director at the Gap about a line of Pride t-shirts the company was working on in honor of Stonewall’s upcoming 50th anniversary. Avram, an artist, writer, and activist most famous for his work with Silence=Death, is someone Carrie considers a “partner in crime” when it comes to agitprop. Carrie, a faculty member at Hunter College as well as an artist, said she’s been concerned about the “shortage of knowledge about recent history” in the queer community for quite some time, and in that context was interested in talking to the Gap. She assumed they would want to talk about Dyke Action Machine, the public art project she founded in 1991 with photographer Sue Schaffner, that had previously spoofed the Gap (as seen in the original tweet above), but was pleased to hear they were actually interested in The Avengers. “That is also history that needs to be exposed,” she said. “You know, [The Lesbian Avengers are] pretty unknown to most people.”

When I asked Carrie about the inspiration behind her original design, she spoke about her excitement of public art and activism coming together in the 80’s and the 90’s with a level of creativity and inventiveness. “There was this feeling that something both explosive and seductive was possible,” she said. “The idea of creating something… really potent and kind of suggestive… that felt really important and energizing for people, that’s always the goal.”

Carrie described a lot of back and forth with the Gap, but she eventually agreed to have her work featured in the line of 2020 Pride shirts, thinking it would be a good way to get the history of The Lesbian Avengers out to a large group of people. “I’m interested in getting the history of this group out,” she said. “And maybe it’s because Dyke Action Machine is embedded in my brain, but the idea of having this sort of mass dispersal of t-shirts, was like, wow, this is a way to get information out that seems really expedient and interesting to me.”

She sold the design for $7000, with the intention of donating the entire sum of money to The Lesbian Herstory Archives.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit the United States, and Carrie’s wife got sick with COVID-19. Suddenly the partnership with the Gap was not really at the top of anyone’s mind, least of all Carrie’s. “The truth is,” Carrie said, “we sort of all forgot about it.”

The next time Carrie and Maxine thought about the Lesbian Avenger Gap t-shirts was last month, when a friend reached out and asked if they had signed off on it.

The Gap had started advertising its Pride collection — but had not bothered to inform Carrie or Maxine that they had gone ahead with the Lesbian Avengers design. While the original plan was to launch shirts featuring multiple activist organizations in 2020, the Gap instead included the Lesbian Avengers design in a more generic 2021 rollout, which is currently billed on its website as “The Gap Collective Pride: an ongoing product collaboration celebrating the spirit of activism and the energy of forward movement. Featuring artists from around the globe and within our own community.” Carrie said the Avengers shirt is a limited-run contract that only applies to this year and that only 1100 shirts have been produced.

When I saw the conversation about these shirts splashed across social media, it was with outrage at the assumption that the Gap was profiting off of lesbian activism. Many community members felt protective of the logo and the original Avengers, and felt angry and disgusted that the Gap stole Carrie’s work. Others were dismayed about the text that went along with marketing the shirt, which originally looked like it included individual names of the founding Avengers without their consent.

When Carrie and Maxine learned about the shirt and the controversy, they were just as surprised as anyone. Though they had signed off on the logo and written a text description to go on the back of the shirts, they did not receive notification from the Gap that the shirts were in production.

Maxine looked up the text on her laptop and realized the description that was upsetting everyone, the one that included specific names of activists, was indeed what she and Carrie had originally written. They had been asked to come up with about 100 words describing the Lesbian Avengers to go on the backs of the t-shirts, and they used documents from Maxine’s personal collection at the Lesbian Herstory Archive to put together a description. Initially they actually wanted to use the individual names of the founders, because, as Maxine explained, when it comes to lesbian activism people often leave out the names and as an archivist she believes it’s important to name people. But the Gap insisted they remove the names because of potential legal issues.

Maxine said that as far as she’s concerned, the names are part of the public domain now, but she acknowledged that companies and brands get nervous about these kinds of things. So they removed the names from the description, but made sure to keep the information about the Dyke March because it felt important to acknowledge that history and celebrate the future of that action. “We really wanted to have it be forward pointing, like this is the genesis of where Dyke March has come from, this is the group that founded that,” Carrie said. “Yeah,” Maxine said, “we changed the last sentence so that it said that there were Dyke Marches that were being held all over the world now.”

However, sometime between the original back and forth and when the shirt and the description on the website were created, Carrie’s contact at the Gap left. She and Maxine suspect that the person who took over the project wasn’t clear on the final decision about the text and mistakenly put the original language, including the founding activists’ names, on the website, not knowing that the Gap itself had asked Maxine and Carrie to remove those details.

When we spoke back on June 1, Carrie was waiting on confirmation that the actual text on the back of the t-shirt would not include the names of the original activists, and she was confident the mistake would be corrected on the website shortly. Now, the text on the website advertising the shirt shows what should be on the back of the actual shirts, per the contract Carrie originally signed.

While trying to figure out what happened between their last interaction with the Gap and the actual printing and advertising of the shirts, Maxine and Carrie were frustrated that people seemed more interested in speculating than actually listening to what happened. They both mentioned Facebook posts written by people hinting at something untoward occurring, but as far as Carrie and Maxine were concerned, as long as the Gap confirmed that the correct final text was written on the shirts and updated their product description accordingly, all was well.

“People just say whatever they want to, and nobody checks it out,” Maxine said.

There is an idealogical question lurking behind the anger some folks in our community felt when they first witnessed these shirts: is it ever okay to work with a large corporation like the Gap? I suspect some people won’t be satisfied to know that the Gap actually didn’t steal this logo but rather the creator behind it willingly sold her work for the project.

To this concern, Maxine and Carrie both seemed to be impatient.

Maxine pointed out that the logo and the original text on the back (“WE RECRUIT,” goddess bless) have both been ripped off by many for-profit companies in the past and Carrie never received a cent for that work. At least in this case the Gap did reach out to Carrie through the appropriate legal channels and compensated her in what she described as a standard fee for content, and the money will go directly to the Lesbian Herstory Archives. “People started going on and on about doing business with a capitalist company,” she said, “but… we’re not doing anything for that company. We’re doing something for the Lesbian Herstory Archives and for the lesbian community by getting the information out to people who would not otherwise know it. So you know, that seems fine to me. I won’t apologize for that.”

Maxine also noted that the founders of the Lesbian Avengers are not a monolith, and that different individuals may take different routes with their continued activism and with the ways they document the group’s contributions. “There’s a website that is labeled the official Lesbian Avenger website,” she said. “…Nobody asked me about it, and that’s fine! Go for it!” (Full disclosure: if you visit lesbianavengers.com you will find a headline stating “SUPPORT LESBIANS! NOT THE GAP!” with a link to purchase a t-shirt with the Avengers logo on it, where profits will support the Lesbian Avenger Documentary Project.)

For Maxine and Carrie, choosing to work with the Gap to get the logo and the history of the Lesbian Avengers out to the masses still remains a choice they stand by.

“I think for me, the issue is still about avenues of propaganda,” Carrie said. “The idea that some kid somewhere is going to open up the Gap Pride Collection and see the Lesbian Avengers t-shirt, there’s just something about that that makes me very happy.”

Editor’s Note, 6/17/21, 12pm: Today, on June 17, I heard back from Carrie with another update. After waiting almost three weeks to hear confirmation from the Gap that the copy on the back of the shirts would match what both the company and the artist agreed upon, excluding the names of the original founders, she finally received word that they did not. As previously mentioned, the art director she was working with left in the middle of the pandemic. The correction was never made.

Because of this, Carrie has asked the Gap to take the shirts off their website and out of circulation for resale. The “take down” is supposed to happen tonight.

“It seems like the baby dykes in the hinterland won’t be able to get their Avengers t-shirt after all,” she concluded.

Editor’s Note, 6/17/21, 5pm: Later this afternoon, I was contacted in the comments of this article by Anne-christine d’Adesky, one of the founders of the Lesbian Avengers, who disputes some of Carrie’s claims. This story is ongoing and will be updated with further reporting as it’s made available.

Editor’s Note, 6/18/21: On Friday, June 18, Cofounders Anne-christine d’Adesky, Ana Maria Simo, and Sarah Schulman of the NY Lesbian Avengers released an open letter to The Gap and to the media. The letter states “Our lesbian history and movement are not for sale.” You can read the full text to the letter here.

The Lesbian Herstory Archives Guard Our Past, Give Us Hope for Our Future

I stood on the sidewalk in front of the Lesbian Herstory Archives for ten minutes before coordinator Maxine Wolfe found me. I was early, because I had been worried about being late, and I knew as I saw her approaching me and the building that she was family. She seemed to know me in the same way, a gift I’m not always granted in queer spaces. We greeted each other and she invited me in. We climbed the stairs of the brownstone together, and when she opened the door we discovered Saskia Scheffer, the other coordinator I was scheduled to meet that Sunday, was already there.

Saskia and Maxine, my guides at the Lesbian Herstory Archive

I hadn’t visited the building since I last lived in New York five years ago, but I immediately felt at ease. We sat down at a long table in the dining room and Saskia offered me some grapes; we chatted about Southern Oregon and the rural land dykes I used to live with; Saskia asked me how exactly she and Maxine could help me.

“I think I’d like to bring the archives directly to our readers,” I said. “I’m interested in primary sources. I’m interested in research. I’m interested in every single facet of lesbian life and I’m interested in what you find fascinating here. Most people don’t get a chance to be up close to our history… I’d like to share how magical this place is by showing off some of its collections.”

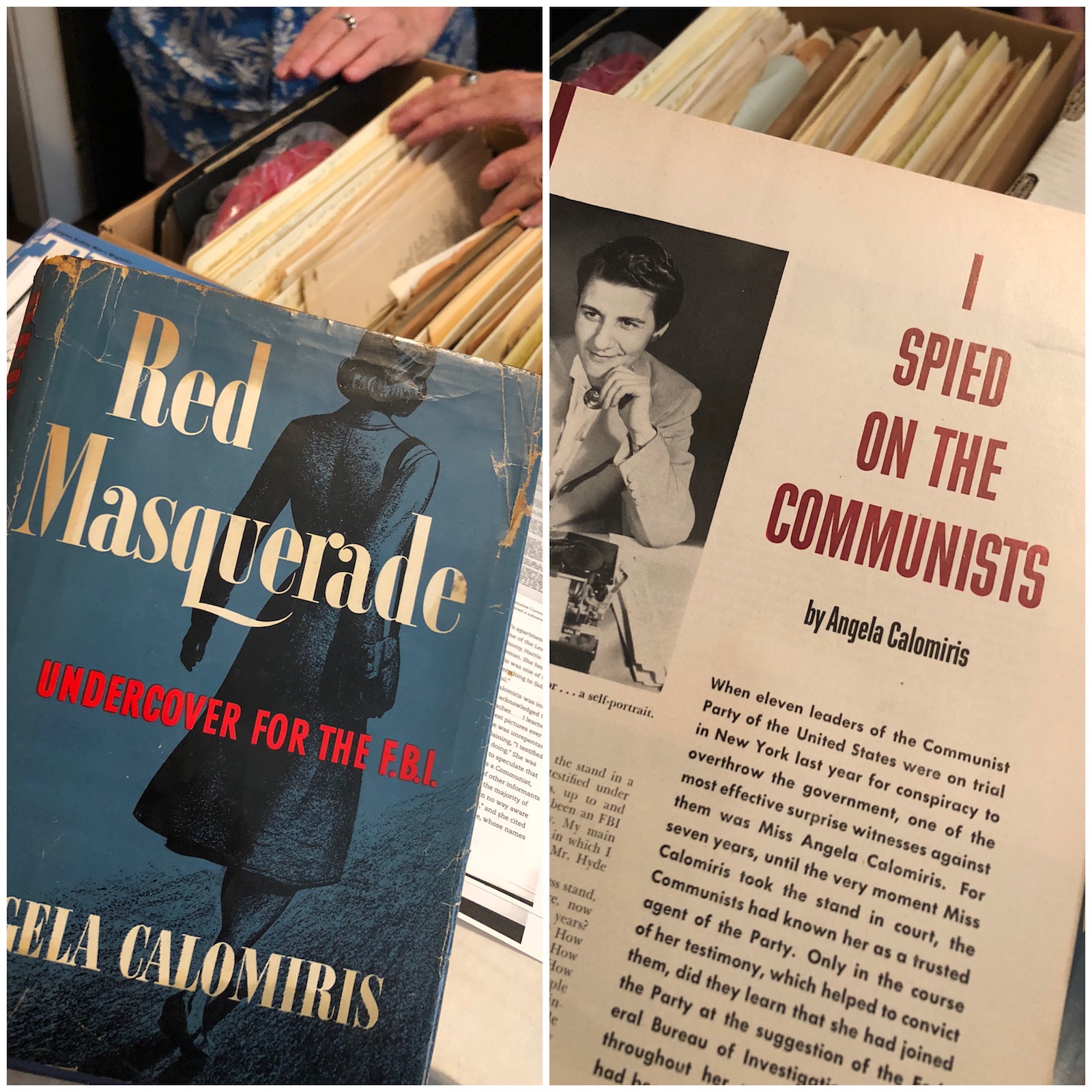

Saskia and Maxine nodded, both agreeing that examining some primary sources would be much more fun than sitting at a table “trying to tell you everything that’s ever happened to us in ten minutes or less.” My friends Dana and Lydia showed up and the five of us climbed a staircase leading to a small room filled with carefully labeled cardboard boxes and filing cabinets. We chose two collections to look at: the Angela Calomiris boxes and the Lesbian Avenger boxes.

“Wow,” I breathed, as Saskia lifted the lids off the Angela Calomiris boxes, and she smiled.

Angela Calomiris was a lesbian FBI informant, and I know a little bit about her story because we’ve written about her on Autostraddle. But suddenly I was holding a file folder filled with her personal papers. A red beret in a clear ziplock bag sat neatly on top of the folders. I asked if Dana could model it for me, Saskia confirmed that she could, and then my sweet queer friend was standing in a brownstone in Brooklyn in 2018 modeling a beret that belonged to a morally questionable lesbian in the 1940s.

“It’s always ‘wow’ when we look at the collections,” Saskia said. Maxine nodded and explained that one of the goals of the archive is to make it so that any lesbian can find an image of themselves housed in this space. “We don’t keep people out just because they don’t fit our point of view.”

Dana modeling Angela Calomiris’s red beret at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

As I reported in June 2012 in the first article I ever wrote for Autostraddle, The Lesbian Herstory Archives: A Constant Affirmation That You Exist, the Archives contain the world’s largest collection of materials by and about lesbians in a beautiful brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. These materials include books, newsletters, photographs, unpublished papers, periodicals, zines, audio-tapes, CDs, records, DVDs, videos, t-shirts, buttons, banners, and more. The Archives no longer keep all of their materials in the brownstone itself; there’s so much to store that a lot of it lives off-site. Our herstory is so large it doesn’t fit in the confines of this large home.

I say home because the Archives aren’t just a building; there’s always a caretaker living in the brownstone, which “makes it a home, not just an institution,” Maxine said. The place certainly feels like a home — non-descript on the outside, when you walk in you’re greeted with a large open library, complete with a comfortable sofa to do some reading and a ladder to reach the books on the highest shelves. There’s a dining room and a kitchen area, and upstairs are the rooms filled with treasures like the collections Saskia and Maxine shared with us.

From the Angela Calomiris’s special collection at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

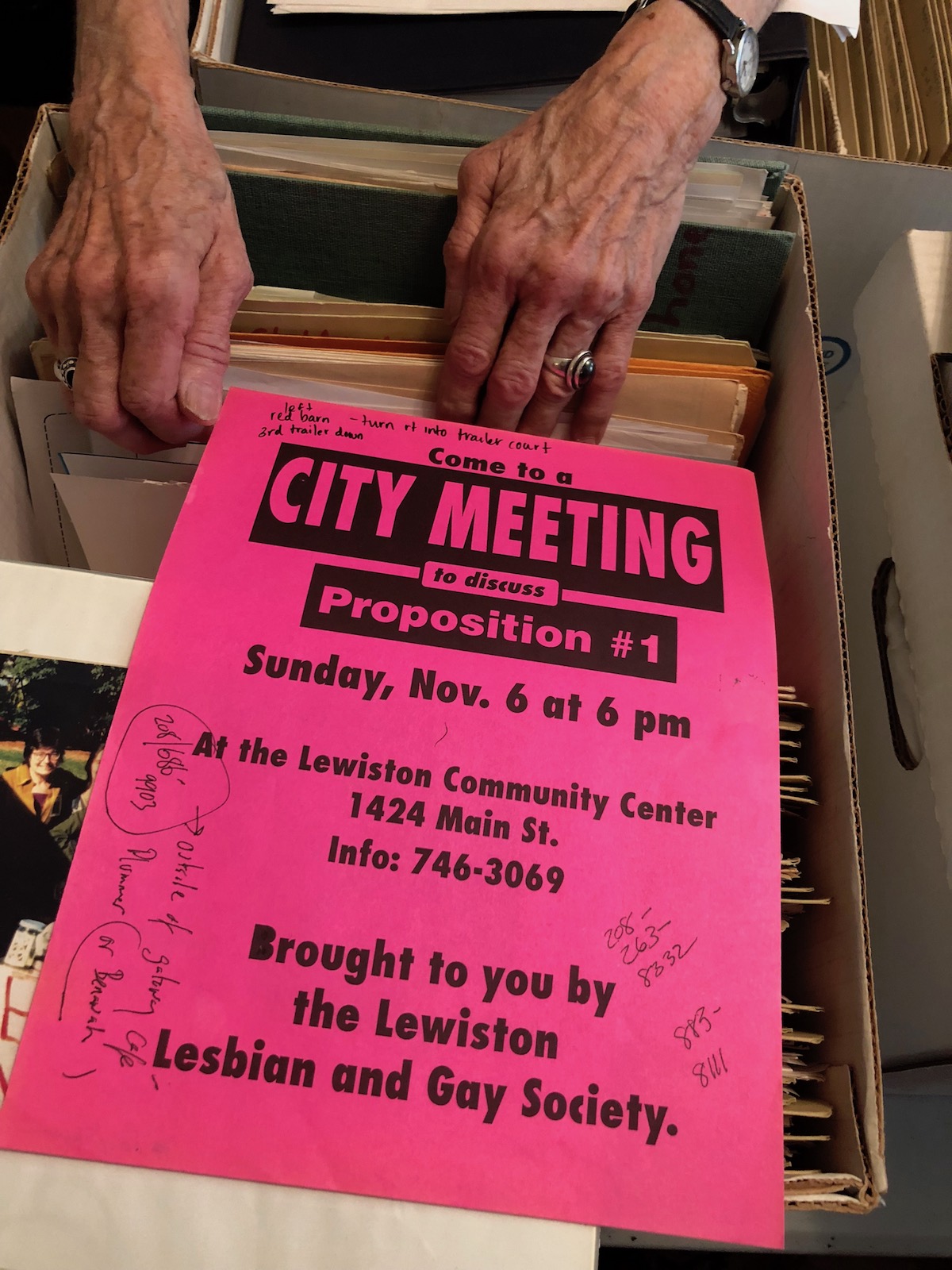

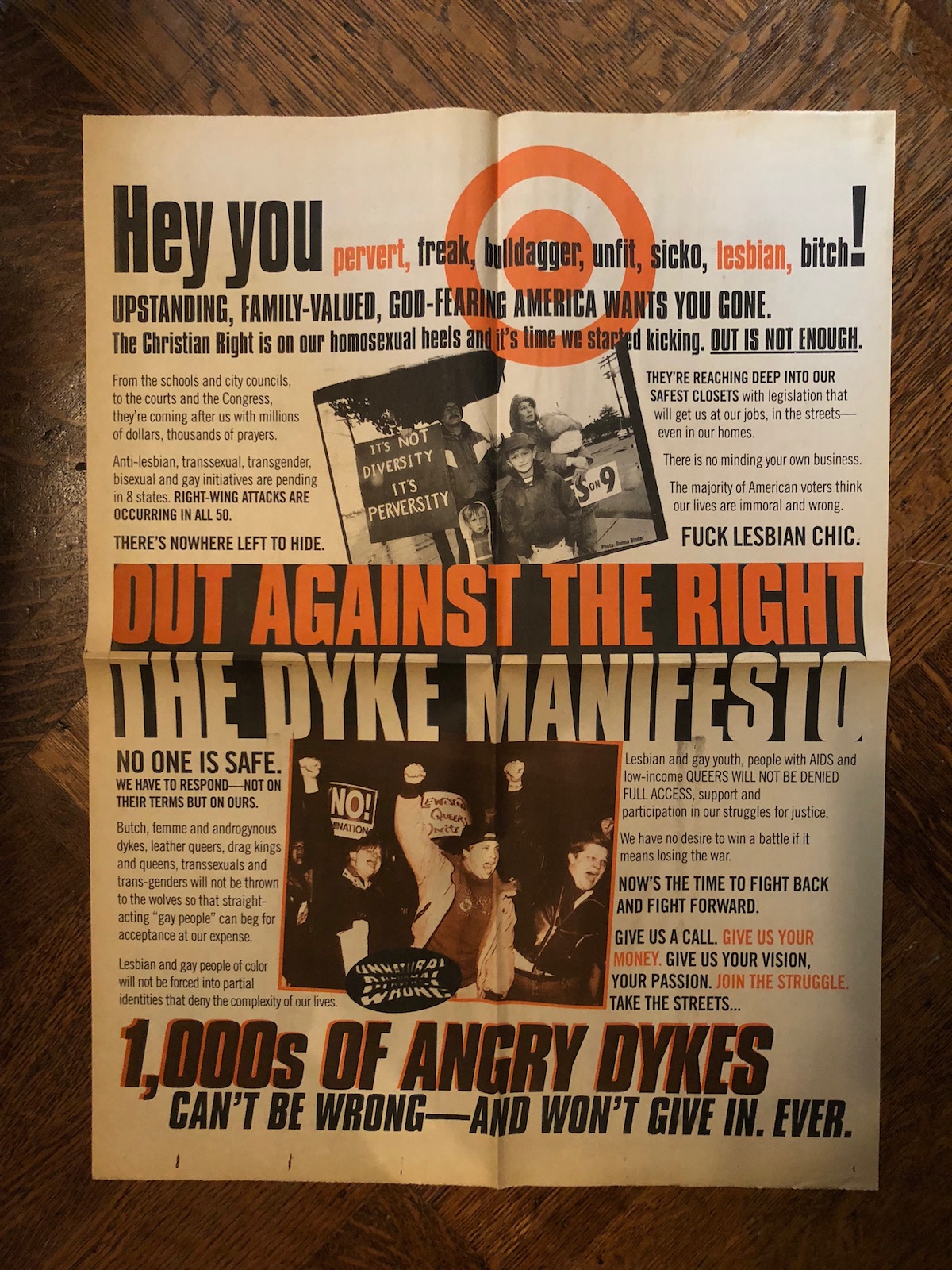

After we put the Angela Calomiris boxes away, we moved on to the boxes carefully labeled “Lesbian Avengers.” These boxes told the story of a dyke activist group defeating the Christian Right in Rural Idaho through direct actions and on the ground organizing. While Saskia stepped back to photograph the flyers and newspaper clippings we were now all poring over – she’s in charge of the Lesbian Herstory Archives Instagram account and is always thinking about the next item she might post online – Maxine explained in what it was like being a part of the Lesbian Avengers in the early 90s. She spoke with authority and I could easily imagine her 25 years earlier: renting a house in Lewiston, Idaho with her fellow activists and organizing with the local lesbian and gay community there, going door to door, hosting pancake breakfasts, phone banking, and eventually defeating Proposition One.

Maxine, looking through the Lesbian Avengers special collection files at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

“How did you get involved with the Lesbian Avengers?” I asked her, feeling inspired and wondering which group I might join in 2018 to best lend my activist energy. That’s when Maxine told me she was one of the founders.

Saskia chuckled from her corner where she was photographing a large newspaper ad and spoke affectionately: “Max is a starter,” she said.

My embarrassment was overshadowed by the jolt of emotion at hearing the tender, casual tone Saskia used to say “Max.” How long had these two women known one another? What had they witnessed each other accomplish? How awesome to witness such love, such herstory, in real time. I chose to let my embarrassment fall away, let gratitude wash over me instead.

From the Lesbian Avengers special collection files at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

It was Sunday, October 7. Less than 24 hours earlier, Brett Kavanaugh had been confirmed to the Supreme Court. Dr. Christine Blasey Ford had told the truth, just like Anita Hill had told the truth in 1991, and three decades later the people in power still hadn’t listened. We were almost two years into the Trump presidency. Later that day I would read the alarming article in the New York Times titled “Major Climate Report Describes a Strong Risk of Crisis as Early as 2040.” Things were objectively bleak, is what I am saying, the Sunday afternoon I visited the Lesbian Herstory Archives. There have been many bleak days since then, and it’s still October. It’s currently hard to find joy, hard to hold on to hope, hard to allow ourselves to let our guards down.

And yet.

There I was, in a tiny room crowded with boxes upon boxes of special collections at the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, NY. There I was, with two queer friends close to my own age and two lesbian elders who have been fighting for our rights and paving the way for our community to exist since before I was born. There we all were: marveling over our herstory together, being sweet to each other, making jokes that would only land within our community, treating each other like family. Our elders are still around, and they still want to tell us all that they know! Our youth is here and queer and hungry, and we still want to show up to connect and learn and share and grow! We have a common herstory, and it is both tangible and ethereal, housed in a brownstone in Brooklyn and on digital platforms like Instagram, it is precious and sordid and hilarious and brilliant. It is kept safe by a collective, and the collective is all of us.

Things are objectively bleak, and yet.

Dana was extremely good natured and modeled everything I asked her to put on her bod, thank you Dana

As we continued looking through the materials in the special collections, Maxine told us more about the inception of the Lesbian Avengers — “[A small group of us] made a commitment to each other that we would do an action no matter what, because somebody had to do something! We agreed not to bring it down to the lowest common denominator of what everyone [in a large group] was comfortable with because if you do that, you never get anything done and it’s boring!” – and about volunteering with the Archives.

When the project began in 1974, as a small collection housed in Joan Nestle’s personal apartment on the Upper West Side, the goal was for lesbians to preserve their own personal herstories. Being in charge of the process would ensure that they would have control and their stories would not be misremembered or erased. Now, almost 45 years later, in an effort to remain true to the original mission, the coordinators of the Archives still offer volunteer trainings for women interested in helping with the work. These trainings can center around one day projects or can delve into deeper work – if a volunteer has time and interest, one can learn a myriad of archival skills like processing and cataloging.

Dana and I made eye contact while Maxine described these volunteer sessions.

“We’re coming back,” she whispered to me.

“Literally as soon as we can,” I whispered back.

A portion of the button collection at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

Before we left the special collections room, Lydia asked if there were any Greek collections, as that was of special interest to them because of their family background. Saskia quickly procured a folder that fit the bill. I knew I would be blown away by the magic held inside the walls of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, but I’d somehow forgotten the thrill I feel by the magic held inside every older lesbian I’ve ever met. Lydia looked through the Greek folder as my gratitude grew.

We visited the publication room, where volumes upon volumes of every lesbian publication you can imagine live in carefully organized green boxes. We gushed over the button collection on display in the narrow hallway leading from the special collections room to the publication room, and eventually ended our visit back downstairs in the library, where we were delighted to discover a “Lesbian Money” stamp next to the donation box.

Is it a crime to decorate a dollar bill or is it art? Does it matter?

It was time to go – Saskia and Maxine had plans in Manhattan and Dana and Lydia and I were meeting some other queer babes at Ginger’s in Park Slope – but I didn’t want to leave. I’d wanted to share primary sources with Autostraddle’s readers, in an effort to bring the magic of the Lesbian Herstory Archives to a larger audience. But I’d barely scratched the surface of two special collections, and yet the magic was infused in the entire afternoon. We hugged goodbye, and I had Dana take a photo of me sitting on the front steps of the building before we walked away.

I look at the photo now and I know that it was taken at a moment when I had been having a hard time. We have all been having such a hard time.

photo by Dana Kravitz

And yet. I look so calm in the image. I look happy.

I look like I’m home.

You Should Go: Brush Up Your ’90s Activist History with Lesbians to Watch Out For

Photos courtesy of Lynn Ballen/Lesbians to Watch Out For

Picture it, dear reader: you’re on Jeopardy!, ready to conquer your opening round, staring down those blank blue screens with fire in your eyes. And then bam, there it is, first category on the board:

“Lesbian and Queer Activism in 1990s Los Angeles.”

How would you fare? If you’re like me and a) the answer is “not well enough” and b) you live in the LA area, I have great news: the new history and art exhibit Lesbians to Watch Out For: ’90s Queer LA Activism has you covered. It’s what you wish you’d learned in school, but were too afraid (or young, or closeted) to ask.

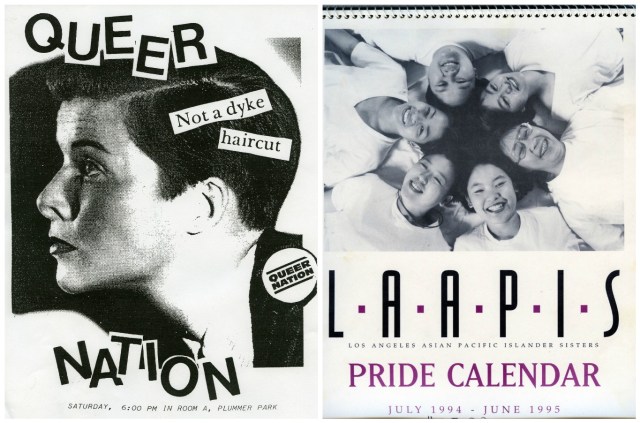

You love ’90s queer ephemera, I love ’90s queer ephemera, let’s go to this exhibit

“The exhibit goes beyond the histories usually told,” explains organizer Lynn Harris Ballen. “It focuses on protest, street activism, and grassroots community groups, and we gathered material from personal collections and oral histories to tell these stories.” That material includes zines; protest signs and stickers; and recountings of queer performances, censorship, and the spaces where activists fought for change around LA and West Hollywood. The diverse multimedia collection highlights organizations like ACT UP LA, Queer Nation LA, the LA Dyke March, United Lesbians of African Heritage (ULOAH), Los Angeles Asian Pacific Islander Sisters (LAAPIS), Lesbianas Unidas (LU), Bi-Net, Transgender Menace (the exhibit is “without question inclusive of trans women”), and the Lesbian Avengers.

Judy Sisneros, another lead organizer, notes that “from the AB101 protests to Hollywood Homophobia actions to organizing for the ’93 LGBT March on Washington, ’90s lesbian and queer women’s activism in LA reflected the energy of the decade: dyke visibility marches, public kiss-ins and declarations of ‘we recruit!'” That’s the kind of cultural history you’ll revisit (or see for the first time) at Lesbians to Watch Out For. I don’t know about you, but I’ll take all the queer resistance inspiration I can get right now, thanks.

The exhibit opens TONIGHT (Friday, June 2) at 7:00 pm at Long Hall in West Hollywood’s Plummer Park, with music, protest sign and button making, vintage stickers and zines, video, and the documentary Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire Too (more info at the opening night Facebook event). It will be open on weekends through June 30 (Fridays 6:00-9:30 pm, Saturdays and Sundays 1:00-6:00 pm), with the exception of June 9-11 because of Pride logistics.

And! As if that wasn’t enough, Lesbians to Watch Out For is also hosting a Grassroots Organizers Tell All panel at Plummer Park’s Community Center at 7:00 pm on Wednesday, June 14. Panelists include Liz Friedman (Queer Nation), Alice Y. Hom (AAPIP Queer Justice Fund), Lisa Powell (ULOAH and Black Lesbians United), Helene Schpak (ACT UP), and Anne-Christine d’Adesky (Lesbian Avengers), moderated by San Diego State University professor and former Lesbian Avenger Yetta Howard. They’ll be looking back at what worked and what didn’t in 1990s organizing, giving advice to today’s young queer activists, and discussing what they’re learning from current resistance movements.

On board yet? Cool, me too, see you there!

Lesbian Avengers and the East Village Panel Is Happening Today and You Can Watch It

Feature image by Carolina Kroon

Hey you! Yeah, you! What are you doing today? I mean, after brunch and before going to a Meet-Up. Nothing?

Well, you’re in luck: today Autostraddle is a proud sponsor of a very exciting Lesbian Avengers event happening in at Dixon Place in New York City. (Did you read Kelly’s post yesterday about the Avengers? Go read it!) But since only some of you live in NYC, this event is actually going to be live-streamed from 3pm-6pm est, which means you can watch and ask questions/chat from wherever you are, as long as you have a computer in front of you! This is the first time we’ve sponsored a live-streamed event, and we’re really excited about it.

Some more about the event: this is going to be a panel/roundtable discussion about the East Village and the Lesbian Avengers featuring playwright and Avenger co-founder Ana Simo, performer Carmelita Tropicana, filmmaker and Avenger Su Friedrich, videomaker and Avenger Harriet Hirshorn, musician and Avenger Eve Sicular, and other special guests.

Some more about the event: this is going to be a panel/roundtable discussion about the East Village and the Lesbian Avengers featuring playwright and Avenger co-founder Ana Simo, performer Carmelita Tropicana, filmmaker and Avenger Su Friedrich, videomaker and Avenger Harriet Hirshorn, musician and Avenger Eve Sicular, and other special guests.

The East Village of the ’80s and ’90s was a hotbed of dyke activism, a laboratory of queer identity, and flashpoint of a nationwide culture war declared by Pat Buchanan at the 1992 Republican National Convention. As our rights as queers and as women hang in the balance of the upcoming election, it’s never been more urgent to revisit the strategies of our radical roots, and ask: are the Lesbian Avengers ancient history, or are they just what we need to reignite the revolution?

This is an incredible opportunity to talk to some Lesbian Avengers and hear their amazing stories. Hope to see you there!

Live broadcasting by Ustream

Herstory Live: The Lesbian Avengers School You On Their Ass-Kicking Roots

Join us on Saturday, October 13, from 3-6pm EST, as the Lesbian Avengers host a live-streamed roundtable and panel from Dixon Place in NYC. The panel will feature playwright and Avenger co-founder Ana Simo, performer Carmelita Tropicana, filmmaker and Avenger Su Friedrich, videomaker and Avenger Harriet Hirshorn, musician and Avenger Eve Sicular, and other special guests.

Explore the Avengers’ roots in the East Village of the ’80s and ’90s, which was a hotbed of dyke activism, dyke art, laboratory of queer identity, and flashpoint of a nationwide culture war declared by Pat Buchanan at the 1992 Republican National Convention.

This is an incredible opportunity to chat with Avengers and hear their amazing stories, so don’t miss it!

![]()

There used to be a saloon next door run by this German-American anarchist Justus Schwab (1847-1900). All the radicals would hang out there, including Emma Goldman and Ambrose Bierce. I only know because they put up a plaque a couple months ago. Maybe I’ll put my own up here. “At this spot, in 1992, the Lesbian Avengers were founded by resident Ana Simo and her co-conspirators Maxine Wolfe, Sarah Schulman, Anne-christine d’Adesky, Marie Honan and Anne Maguire.”

It was an iffy proposition, starting a lesbian direct action group, and required a good dinner and lots of wine, as most revolutions do. In the ’90s, lesbians fought against AIDS, and for abortion and women’s health care. They stood up for animal rights and sweat shop workers. But for lesbians, as lesbians? Not so much.

For this, the neighborhood made its contribution, almost as much as all the talent and experience in the room. Five of the six lived and worked in the East Village, perfectly matched to the cheap rent and rabid dissatisfaction apparent in the street. Every flat surface had a sticker on it, or flyer. Lampposts were perfect for pink triangles announcing Silence=Death, or posters advertising for an ACT-UP or WHAM (Women’s Health Action Mobilization) demo, or poetry slam. Ads weren’t always what they seemed. Sometimes they were advertising movies. Sometimes, if Dyke Action Machine was involved, they might be offering co-opted images of lesbian power.

It was a kind of evolutionary soup, a crucible of artists and queers, and activists, with an enormously long history of agitating immigrants. And since at least the late ’70s, when projects like the all-dyke Medusa’s Revenge Theater started up, it had been a laboratory of identity. If you weren’t careful, a bite from a radioactive Spiderwoman might transform the quirk of your sexual orientation that you thought was either a horrible tragedy or just a spare appendage, into an intrinsic, essential part of yourself. New superhuman powers included X-ray bullshit detection, and the instant assessment of the web of life.

That’s why ACT-UP didn’t just take on one hospital, one bigoted priest, but the entire church, the whole medical system, the government that supported it, the nation that held it all in place. And why at WOW, Women’s One World theater, lesbian performers like Holly Hughes, author of The Well of Horniness, Carmelita Tropicana, and later the Five Lesbian Brothers, didn’t just separate themselves off to the side, they re-envisioned the entire world.

I was still pretty fresh from the potlucks and softball dykes of Kentucky when my friend Amy Parker took me to see the Brothers at WOW. My god, they blew my mind. The intrigue, the sex, the hilarious, unmitigated muff-diving desire. They didn’t just put our dyke selves front and center. They reduced the outside universe to a mythology fainter than shadows on a cave wall. You could play with them, or laugh at them until your face cracked.

That’s what made queers so dangerous in the ’80s and ’90s. We were getting bigger and bigger. Indivisible. Taking up more space. Imagining ourselves as part of the city, of the country. In his essays written in the death throes of AIDS, David Wojnarowicz took on all of America. “My rage is really about the fact that WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.”

That’s what made queers so dangerous in the ’80s and ’90s. We were getting bigger and bigger. Indivisible. Taking up more space. Imagining ourselves as part of the city, of the country. In his essays written in the death throes of AIDS, David Wojnarowicz took on all of America. “My rage is really about the fact that WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.”

Poet Eileen Myles didn’t just stick to her poems but ran for president in ’92. If a bastard like Pat Buchanan could run for president, somebody like Myles had better, too. And just a couple weeks before the Lesbian Avengers’ first action, the failed presidential candidate Buchanan went to the ’92 Republican National Convention in August, and gave a speech declaring war, a Culture War, complete with a blitzkrieg campaign to divide and conquer those minorities increasingly encroaching on straight white male power. He set the “brave people of Koreatown” in opposition to the (black), welfare-ridden mobs of the LA riots, and unleashed everybody against the bra-burning feminists, tree-huggers, and homos.

“Friends, this election is about more than who gets what. It is about who we are. It is about what we believe and what we stand for as Americans. There is a religious war going on in this country. It is a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as the Cold War itself. For this war is for the soul of America.” – Buchanan

It was good to have it spelled out. It confirmed the decision of those first six Avengers to go big, launch the group by taking sides on one of the most important issues in New York City: the Rainbow Curriculum. Its purpose was to teach school kids tolerance, mostly of racial and ethnic difference, but also of women and queers. But even though only a few of the 400 odd pages mentioned lesbians or gay men, the Christian Right used queers as a wedge in their D & C campaign, and attacked it as the “gay” curriculum. By getting involved, the Lesbian Avengers not only inserted a lesbian voice into the city, but entered the nationwide battle for the soul of the country.

The first action is still almost unthinkably daring. We didn’t chain ourselves to anything, or clash with cops. We stood outside an elementary school in Queens as open dykes, and gave balloons to school kids that encouraged them to, “Ask about Lesbian Lives.” Some of our tee shirts read, “I was a lesbian child.”

The rest is history. The Rainbow Curriculum got squashed, but not the Avengers. Dykes everywhere embraced our in-your-face mix of humor and anger, and the goal of lesbian visibility. Two years after that first action, the fire-eating Lesbian Avengers had become an international lesbian movement. We mobilized twenty thousand dykes for a march on Washington, and almost as many for the International Dyke March in New York. There were more than sixty chapters worldwide. As a legacy, we left behind Dyke Marches that continue from San Francisco to London, and a changing cultural space we helped expand. Especially inside dyke brains.

next: read an excerpt from Kelly Cogswell’s upcoming work, “Eating Fire,” describing the Lesbian Avengers’ first demonstration in front of an elementary school

+