8 Books Featuring Asian and Pacific Islander Queer Women

Hey queer book nerds! Don’t forget to keep the Ask Your Friendly Neighborhood Lesbrarian queries coming! Email me at stepaniukcasey [at] gmail.com or tweet at me @canlesbrarian. Today:

Hi Casey!

Love your column. Do you have any recommendations for books featuring Asian and Pacific Islander lesbians? For example, I’d count Huntress by Malinda Lo, I Can’t Think Straight by Shamim Sarif and Scale Bright by Benjanun Sriduangkaew. But that’s all I got… There’s quite a few books where queerness is a veiled mention (looking at you Disappearing Moon Café), but I’m not looking for that. I want my queerness to be blatant, dammit!

Angela

Angela, I would love to find you (and Autostraddle readers) books with Asian and Pacific Islander lesbian characters! I feel you on wanting the blatant queerness. I remember Disappearing Moon Café — a sweeping multi-generational novel about a Chinese Canadian family by Sky Lee — being great, but don’t recall anything queer. I’m glad it’s not just my bad memory! But not to fear, because there are plenty of books with out and proud queer Asian and Pacific Islander ladies that you will not forget.

I’m excited to introduce these books with API queer women, both for API queer women looking for mirrors of their identities and experiences and for other readers who can look through a window into different queer lives. If anyone hasn’t read the books Angela mentioned, definitely check those out too! Malinda Lo and Shamim Sarif are go-to Asian lesbian authors for their respective genres (YA and romance). Honestly, my only problem with this question was deciding which books to talk about! I decided to go for under-the-radar books from diverse genres and forms, including literary fiction, poetry, historical fiction, a graphic novel, YA, and one genre-defying mythological novel/fairy tale.

Small Beauty by jia qing wilson-yang

Small Beauty is a quiet, meditative novel about family and identity that more than lives up to its name. The main character is Mei, a young queer trans woman who’s dealing with the mysterious death of her cousin and all of the details of arriving in a small town where she’s inherited his house. While she’s there, she uncovers some secrets — like that she isn’t the only queer in the family — and spends a lot of time reflecting on being trans and having white and Chinese ancestry. wilson-yang does an incredible job portraying Mei’s life as both the extraordinary and unremarkable thing that it is, whether it’s dealing with transmisogyny (there’s one scene of transphobic physical assault and some transmisogynist so-called feminist rhetoric), using Mandarin words, or talking about Chinese food. It makes for a beautifully introspective book.

Babyji by Abha Dawesar

Babyji is an intense and intensely funny book set in New Delhi about a 16-year-old woman named Anamika discovering her queer sexuality. Dawesar perfectly captures the heady, whirlwind feeling of teen sexual awakening. But even the earliest out and proud of us probably weren’t juggling three women at her age, including an older divorcée, a classmate, and a domestic worker from her house. Anamika is a delightful, charming character, wise in some ways and incredibly naïve in others as teens tend to be. She’s wonderfully complex: a head prefect at school with a serious penchant for quantum physics, and a confident tomboy thinking critically for the first time about the caste system and how others are affected by it. Be prepared for some hella sexy scenes.

Prairie Ostrich by Tamai Kobayashi

An historical novel set in 1970s rural Alberta, Prairie Ostrich is about a family trying to deal with their demons. It’s told from the perspective of eight-year-old “Egg” Murakami, as she watches everyone in her family grieve in their own destructive ways after her brother’s death. The family is also never far from the history of internment and forced relocation of Japanese Canadians during WW2. The only one holding the family together is Egg’s older sister Kathy, a queer teen who wants so desperately to shield Egg from everything bad in the world that she changes the endings of the books she reads to Egg: she tells her Charlotte and Wilbur live happily ever after! It’s fascinating to witness the teenage lesbian romance from Egg’s eyes; she doesn’t really get it, but at the same time she kind of intuitively does? Egg’s innocent and inquisitive perspective give the whole novel a beautiful, quiet power.

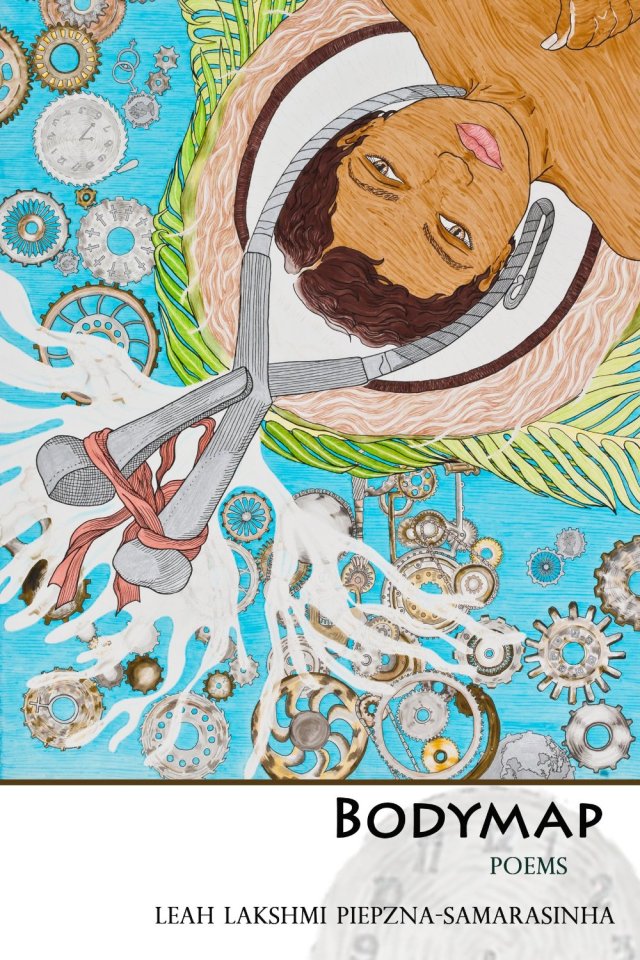

Bodymap by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

If you need some powerful words to get you through tough times, look no further than Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s 2015 poetry collection Bodymap. It is an incredibly tight, accomplished collection of poems, full of gorgeous, evocative images and raw emotion and vulnerability. The poems are tough but soft, and undeniably visceral, just like the hard femmes she praises in the poem “my city is a hard femme.” Although it’s a slim book like many poetry collections, Piepzna-Samarasinha packs in a lot of topics, including love, relationships (falling apart), disability, queer brown femme friendship, finding your people, and the Sri Lankan diaspora. Hers are the kind of words you want to post on your fridge, and look at every day to remind yourself that you’re powerful. (Read Carmen Rios’s full Autostraddle review.)

Tahuri by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku

This collection of interlinked coming-of-age short stories is about two young Maori women, Tahuri and Whero, who are both in the process of realizing they’re lesbians. Beautifully written, some of the stories are quiet and gentle, while others confront the rough reality of being Maori women in colonized Aotearoa/New Zealand (including sexual assault). The stories have a strong sense of place, which is clearly important to both characters, as it’s intimately tied to their culture and identities. The journey of coming to terms with their queer sexuality is culturally specific as they search for belonging as lesbians — or, wahine takatāpui in the Maori language — within Maori culture with few visible role models. A staunchly feminist, decolonizing book, Tahuri is a celebration of both queer women’s sexuality and Maori women’s strength.

Shortcomings by Adrian Tomine

This graphic novel about 20-something Asian Americans in California trying to figure out how to be happy in and out of their relationships holds no punches. Tomine presents his characters — including a Korean American lesbian named Alice — with brutal, unflinching honesty. He has no qualms about airing their shortcomings like dirty laundry for everyone to see, and he’s not afraid to ask tough, complex questions, like: How can we separate our desires from the unavoidable racism and misogyny we grow up with that inform our ideas of what is attractive? Alice is the main character Ben’s BFF, a short, chubby ladykiller dyke with a firm belief in telling it like it is (including some casual biphobia that I wish wasn’t so true to life). You’ll be glad to hear Shortcomings ends with happy lesbians and miserable straight dudes.

When Fox Is a Thousand by Larissa Lai

When Fox Is A Thousand is part folklore, part fairy tale, part historical fiction, and part contemporary urban story. It’s a slow burn, beautifully told tale from three alternating viewpoints: Yu Hsuan-Chi, a real-life poet from ninth-century China; the mythological Fox, nearing her one thousandth birthday; and Artemis, a young Chinese Canadian woman living in Vancouver. Lai skillfully weaves together Chinese mythology, medieval Chinese politics, and the rhetoric of modern-day social justice to create a unique tapestry of stories. Each of the characters has romantic relationships with women and Lai explores what is the same — and what is different — about dating women in the T’ang dynasty, in the surreal world of mythology, and in contemporary North America. Danika at the Lesbrary says this book should be considered a lesbian classic.

Women Loving: Stories and a Play by Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz

I love how just to make it absolutely clear this book has lesbians in it, Filipina author Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz decided to call it “Women Loving,” with a fun play on women as both subjects and objects of desire. This is in fact a groundbreaking book, being the first single-author anthology of lesbian-themed writing in the Philippines when it was published in 2010. In this sexy collection written by someone who’s a part of the community she’s writing about, Cruz shows Filipina women choosing to love women even in sometimes treacherous and inhospitable circumstances. She gives readers in the Philippines a rare glimpse at what that love — romantic and sexual — can look like. Focusing on the rewards for Filipina lesbians of living true to themselves, Cruz also doesn’t shy away from the topics of loss and struggles with homophobia.

Bonus! You should also read Heather’s recent interview with queer YA superstar Malinda Lo. They talked about her upcoming book A Line in the Dark, which features a Chinese American queer teen girl and deals with loyalty, love, friendship and murder!

And, finally, be sure to check out these books that I’ve written about in previous columns: Not Your Sidekick by C.B. Lee (bisexual Vietnamese Chinese character), My Education by Susan Choi (bisexual Korean white character), Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s graphic novel Skim (Japanese lesbian character), Landing by Emma Donoghue (Indian Irish lesbian character) and The Stars Change by Mary Anne Mohanraj (a whole bunch of South Asian queer characters).

Sins Invalid’s “Birthing, Dying, Becoming Crip Wisdom” Features Crip Art, Activism, Love & Liberation

“Disability is a common human experience and yet it’s made invisible and shamed. So we always hope audiences leave our shows with a greater capacity for self-love.” A decade after cofounding the performance collective Sins Invalid, executive director Patricia Berne maintains a bold vision for its work: disability justice must be born out of intersectional collective struggle, lead by those most impacted by systemic oppression. In preparation for the world premiere of its latest, Birthing, Dying, Becoming Crip Wisdom, Autostraddle spoke to Berne and performer Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha about centralizing queer and gender non-conforming disabled artists of color in crip art, activism, love and liberation.

Tovah: I was moved by the show’s title, specifically the phrase “Becoming Crip Wisdom.” “Wisdom” evokes a very specific way of knowing or unknowing. What does “crip wisdom” mean to you?

Leah: People rarely get to view art that asserts that crips are geniuses. That we have knowledge, that we have life-saving brilliance. The ableist idea that we’re just these huge deficits is so strong. But my whole life is based around the idea that crip wisdom is both the ultimate reality and wisdom that everyone needs to learn from. I see crip wisdom in all the life-giving ways disabled, Deaf, sick and neurodivergent folks mentor each other, giving each other lifesaving wisdom that no doctor’s office will. We are often smarter and more skilled at navigating both our bodyminds and ableism than most medical professionals. Much of what I wrote about for this new show comes from the mentoring I’ve gotten from more seasoned crips and the mentoring I’ve passed on. Crip wisdom is the wisdom of slowing the fuck down and making movements that stay at the pace of the “slowest” members — disabled, parents, older folks, poor folks, caregivers — because when you move at the pace of the majority of people on the planet you have stronger movements.

Patricia: Knowledge is when we take information, facts, and create a system of understanding. Wisdom is when we know something because it’s in our bones. It’s our experience. Some things you just have to live through to really fucking get it. Aging in a disabled body is hard. The demands of ableism take a toll on you. Always having to take an ableist hit when you get on a plane. Or when you don’t have an attendant assistant when you need it. Every time you spend money you shouldn’t have to spend for healthcare. It makes you age faster — seriously. These are some of the themes we explore in the show.

Tovah: Did any recent political or social events influence the writing/performances in this upcoming show?

Patricia: As queer and disabled people of color, all of us have been impacted by the visibility of violence that impacts our communities. The Black Lives Matter movement has spoken to all of us very profoundly. Patriarchal violence against trans women of color hit us very hard. We’ve also all been deeply affected by climate change and the ways US consumerism contribute to the ongoing devastation of our planet, our earth body. All of these things have impacted the way we articulate what it’s like to live and birth and die as crip wisdom.

Leah: Jerika Bolen’s life and murder was very much on my mind throughout the lead up to the show. So were the deaths of many femmes in communities I am part of through suicide in the past year and a half. My piece “all the femmes come back” is about that. I wanted to write about the specific pressures that femmes and crips feel that can increase our suicidality — the intense pressure on us to be perfect, diamond hard and always competent and emotionally laboring because otherwise ableism and femmephobia and transmisogyny and sexism say that we’re crazy, too much, too emotional, too needy. There is a really intense place ableism and femmephobia come together, the “too needy” “don’t ask for help, you won’t get it” place, that is incredibly dangerous.

Tovah: I admire the way Sins Invalid never assumes an able-bodied audience nor strives to appeal to one. Sins has never been interested in “teaching” able-bodied audiences about disability or claiming, “we’re just like you!”

Patricia: If able-bodied audiences want to learn about disability, they can go read a book. This is not the academy. This is a theater space. One of the reasons I created Sins Invalid was because I needed it. I grew up consuming a ton of media and cultural narratives that made no room for disability. I really needed to see a performance like Sins. I needed to see the types of stories told by Sins performers. It’s necessary to reflect disabled bodies as part of the collective narrative.

Leah: We deserve to have art that is by us and for us and is us being complicated and depicting all our lives as they are, without simplifying or reassuring. I think one of the most important things about Sins is that it’s not for abled people — they can come, but in the words of the great disabled poet Laura Hershey, “Don’t do us any favors.”

Tovah: What role does sex and sexuality play in this show?

Patricia: There’s the idea of the perverted cripple. It’s so tired and so predictable. I’m not against being a pervert. I’m a down pervert! But it’s a trope. It’s either that or we’re sexless. People with impairments do not battle the myth of the virgin or the whore, but a counterpart — are we saints? Or monsters? The reality is that both are ableist projections and we have to go between myth and fantasy to find the truth of what we want and need as people.

Leah: My pieces in the show aren’t erotic the way a lot of folks might think of erotic, but they are sexual because they are me, in a hot dress and a cane, being the midlife crip femme leather witch of color of my dreams. They are me invoking that we all stay alive.

Tovah: What’s next for Sins?

Leah: More sex, more brilliance, more survival, more beyond survival. And more access — I am so proud of how every show has more access. Crip wisdom is in all of our movements.

Sins Invalid‘s Birthing, Dying, Becoming Crip Wisdom plays at the ODC Theater (351 Shotwell Street/17th Street, San Francisco) Friday 10/14 at 8 pm, Saturday 10/15 at 8 pm (ASL interpreted and audio described) at 8 pm and Sunday 10/16 at 7 pm. Tickets are $25 online or in cash at the door. Wheelchair accessible. Scent free. Other information on collective access available from Sins Invalid.

“Don’t Date Anyone Who Treats You Like Shit”: An Interview with Author Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

“Don’t date anyone who treats you like shit, even a little.” – from my interview with Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

This was supposed to be a book review of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarsinha’s new memoir, Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home.

But it’s actually the story of how reading my friend and queer aunty Leah’s brown femme poetry saved me, made me a writer, and totally revolutionized my love and sex life.

It was the winter of my first year of university, and I was a young, closeted trans woman of color recently run away from home, clinging to my required scholarship GPA by a fingernail, and in the midst of a full-blown depressive episode. A tender young femme from the temperate West Coast, I was unprepared for the icy reality of my new home in Montreal, where temperatures regularly plunge to 40 degrees Celsius below zero. There, ensconced in the darkness of my tiny, filthy dorm room, I lay in bed like a wilting plant, while all around me, rich white trust funders frolicked like a real-life Abercrombie and Fitch ad.

Running away from my abusive parents to start a new, improved, fabulous queer life in gay Montreal wasn’t supposed to be like this. I wasn’t supposed to have no friends, no job, and no plan for the future. I wasn’t supposed to be failing my classes or sleeping all day like a beached whale all bloated up on my own self-loathing. I wasn’t supposed to still be dating guys who didn’t know what consent was (though at the time, I sure as hell didn’t know what consent was either), or having traumatic flashbacks to being raped all the time. I wasn’t supposed to have those constant, creeping thoughts about suicide.

“I know a ton of femmes of color who are single for years, who deal with a lot of scarcity and people who are “afraid” of us or don’t know how to love well, and I know what it’s like to feel like you have to settle because you’re afraid you’re never going to get laid again because I have been that person.” – Leah

I read brown femme poet and author Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha for the first time that year – actually, I stole her debut poetry collection, Consensual Genocide, from the local co-op bookstore because I didn’t have any money to pay for it (and also because I had a little bit of a “stealing problem,” okay?). I didn’t have any real, conscious “queer politics” at the time. I didn’t even know who Leah was. I just liked the cover and the sound of the title.

This was the poem that changed my life:

there is an unexploded land mine heart in us

under every breast chest

waiting for breath

tears a moan

to crack the land open

and let the stories come walking

out of the scar– Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “Landmine Hearts”

These poems were a lighting blast right to my gut, to tender hidden places in my body that silently raged and ached and moaned with memory, history, violence, secrecy, shame. I remember sitting bolt upright, clutching the slender volume with its hand-drawn cover design to my chest. Admiration, indignation, shock, catharsis, jealousy, and blessed relief surged through me all at once.

Who was this “Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha,” anyway, and how could she be evoking these feelings in me? How dare she? Was this even poetry? Why hadn’t anyone ever told me that poems could be like this? That you could write about your own life, your race, about the secret things that happen to children at night at the hands of people who say they love you – who tell you they are doing it because they love you?

“For better or worse, my mom both sexually abused me and was the parent who was the most consistently loving and supportive in my life growing up. She did stuff that almost killed me, and also brought me to the library, encouraged me to go to college, offered me support. That’s my experience.” –Leah

Reading Leah’s poems was how I learned that I – young, Asian, feminine, queer, all the things I had learned to hate about myself – mattered, that my body and my words mattered. This is how I became a poet, a writer, a proud femme transsexual, an incorrigible queer. This how I re-discovered my will to live.

“There is a reason why so many poor and oppressed folks are poets- you can write poetry on the bus, on your phone, in the toilet stall on a five minute work break. Memoir takes longer. The great June Jordan defined poetry as “a means of telling the truth… with maximum impact, minimum words.” I think there is a somatic genius to writing poetry about trauma- poems can be a short container for intense experience. You enter into something really intense, and then it is done and you can breathe.” – Leah

Now, about seven years and a lot of angsty blogging later, I am a lot happier, a lot more comfortable with my femme identity, and actually have friends (!) As fate (or rather, Facebook) would have it, one of them is the sparkly queer brown femme creative tornado that is Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. In person, she is as dynamic and powerful, tender and compassionate, as her poetry. Also, she gives wicked styling tips:

“I’m staying mad that Value Village prices went up but I have a super shopper card and I get emails when they have a 50% off sale, so I try and hit those whenever they happen. I don’t shoplift anymore but I was good when I was younger. (Put library books in your bag and show them when the tag detector goes off, bring a friend’s baby with you, and get into a huge fake fight on your cell phone at checkout when you buy something small, so they just want you to leave.) … I really like going to and throwing femme clothing swaps to get free stuff, and I also support spending money when you have it- there was a point when I realized that all my clothes were super worn out because they were all fifth hand.”

So it was a pretty big honor when Leah asked me to review her latest book – and first published long-form prose work – the memoir, Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home. Dirty River is, essentially, a queer choose-your-own-adventure. In lush, gorgeously evocative prose, Leah writes about running away from abusive blood family, having to run away again from abusive chosen family, and finding out how to build your own home out of (self)-love, (self)-forgiveness, and sheer brown femme badassery.

You can probably see why I’m so into this book. (Buy it, borrow it, or order it online now!)

Other – less unabashedly sentimental – reviewers might say that Dirty River is an important piece of literature for political reasons: among other things, it is among the first memoirs to directly speak to the experience of a South Asian, queer, disabled femme abuse survivor. It also follows up Leah’s previous literary work in taking a rare, honest, unflinching look at the reality of intra-familial sexual abuse and intimate partner violence in queer and activist communities.

All of these things are true. Yet what I also find compelling and beautiful about the book is that it offers both ancestry and possibility to young queer women of color who are struggling to find strength, safety, and self in the midst of so many communities where people call themselves family and then hurt you in the same breath. Leah’s book provides a mirror, an anchor – it lets us know that we are not alone, that we’re not “crazy” or making shit up, and places us within a tradition of femmes fighting for life. You don’t have to put up with lovers who treat you like shit, Leah tells us – but it doesn’t make you weak or a failure if you have.

“I am accountable to the folks who read my work, and if it’s speaking to the queer disabled femme survivors of color who read my work, I’ve succeeded- which is a really different measure of success than most mainstream literary spaces understand literary success to be. I want all my books to feel like roadmaps and records, that we existed and that these are some of the communities and moments in QTPOC crip femme history we made, that this is how we survived.” – Leah

Any sad queer girl of color with a notebook knows: sometimes, books are the only family that you can trust. Dirty River is proud, strong, no-shit-taking, tender-advice-giving Aunty of a book; a sweet herb-smelling, tarot card fortune-telling, crystal earring-wearing embrace that squeezes the tears out of your bruised femme heart and reminds you: You are stronger than you think. You words are truer and more important than you know. You can get cute clothes at Value Village for a dollar on a good day. Don’t date anyone who treats you like shit, even a little.

“Femmes of color are my whole life. As writers, I wanna shout out you [Kai Cheng Thom], Luna Merbruja, Cyree Jarelle Johnson, Neve Be, my partner Jesse Manuel Graves and their femme of color performance project with Devyn Manibo, Cancer Rising. Cherry Galette, Meliza Banales, The Lady Miss Vagina Jenkins, Billie Rain, Patty Berne who co founded Sins Invalid and basically gave birth to the whole disability justice movement. Heels on Wheels. Randa Jarrar, Maya Chinchilla (my homegirl, an amazing queer Guatemalan femme poet who just survived a major car accident and we’re fundraising for her because she’s going to need almost a year of rehab), Stefani Dixon, Adrienne Maree Brown, Micha Cardenas, Reina Gossett. Elena Rose. Chanelle Gallant. Miss Major. There are many, many more. We are not invisible, people just enact femmephobia by not looking for us.” – Leah

So this was supposed to be a book review of my friend Leah’s new memoir. But it’s actually the story of how, a few years ago, I was a scared young trans girl of color who ran away from her parents, who loved her, but hurt her anyway. This girl tried to find herself in a new place, a new community, but all she could find was the same violence, the same fists, the same secrets as before. Then she found a book by a wise brown femme that changed her life and gave her a voice. And with that voice, she’s been telling her own story – and finding new family – ever since.

You can too.

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s “Dirty River”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

As a fan of her vibrant and gutsy poetry, I was excited for Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s memoir, Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home, to come out. Much like her other work, this fragmented narrative is a survivor’s love song about finding identity and freedom.

The book opens with 21-year-old Leah running away from home, leaving her parents for Toronto with a backpack stuffed with fancy clothes, books, and a sex toy. Piepzna-Samarasinha writes gripping journey stories, and the pace picks up as the memoir moves forward. There’s border interrogation. There’s riotous activism. There’s an intense romantic relationship with Rafael, “the mixed-brown-survivor-separated-at-birth brother I’ve been looking for” — a dream that turns into a nightmare when he becomes violent. There’s poverty, illness, escape from abusive family members, and joyous reclamation of a heritage they’d denied. If you’ve ever run away from a rough situation, or wanted to, this memoir will resonate.

Dirty River is a non-chronological narrative, told in fragments. The sequences and relationships of events are not always clear, but the short sections create a frenzied energy. Sometimes the prose breaks into poetry, or diverges into multiple versions of a story, allowing parallel truths to speak. One heart-wrenching example is Piepzna-Samarasinha’s nuanced writing about her mother, who’s both a perpetrator of sexual abuse and a teacher of tools for survival. Delving beyond the written word into the senses of hearing and taste, she includes a “Healing Justice Mix Tape” track list and a two-dollar menu for a “Hard Times Survival Dinner.” This is an honest work that defies neat and tidy narratives, acknowledging that “there’s uplift, but it’s not a straight shot.”

The book shines brightest in its stories of identity. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s white mother raised her to “pass,” while her Sri Lankan father was silent and angry about the history of a family he ran from. The memoir is full of wobbly steps toward learning to “be brown,” owning her Tamil roots, and finding community among punks and activists of color. Reading This Bridge Called My Back, a young Leah realizes: “You can relate to it more than anything else you’ve read, but that’s wrong. The women in the book are that term, ‘women of color.’ You must be faking — what is that? You are just normal. And weird… Are you?” In Toronto, she finds a “place where people were talking, out loud, about a queer/woman of color feminism, culture, and community,” and other Sri Lankans are part of it. There’s a sense of triumph in her re-learning of history, hairstyles, and recipes, and finding allies to fight systemic oppression with. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s coming to terms with childhood abuse is heartbreaking, but equally important. There’s also her claiming of femme identity, associated with rituals of dressing up, navigating the streets, and owning one’s sense of beauty, as well as opening up to lust that transcends past wounds. While Dirty River has fewer sexy encounters with women than poetry collections like Love Cake (though what’s there is great), this memoir will appeal to those seeking a gritty, glorious, multi-layered story of homecoming and self-healing.

Top 10 Queer and Feminist Books of 2015

2015 has been really awesome for giving us all a ton of new queer and/or feminist things to read! Here are some of the best.

The Top 10 Queer and Feminist Books of 2015

10. The Feminist Utopia Project: Fifty-Seven Visions of a Wildly Better Future, edited by Alexandra Brodsky and Rachel Kauder Nalebuff

This collection of essays, interviews, stories, poems and visual art from contributors like Janet Mock, Mia McKenzie, Sheila Heti, Melissa Gira Grant, Yumi Sakugawa and others aims to envision not just a dreamy future but a better one. In her review at Autostraddle, Maddie writes:

“Instead of laying out a definitive blueprint or roadmap or set of ideals, Brodsky and Nalebuff invite the reader to join them and their diverse team of contributors in a creative and collective thought experiment to imagine what the world could be. This book is not a manual to create The Feminist Utopia; it is a process that you are invited to share in.”

9. I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975–2014, by Eileen Myles

This sizeable new collection, along with a reissue of Chelsea Girls, has arguably (finally) brought Eileen Myles to the forefront of the collective literary consciousness and “nothing less than the foremost lesbian poet-hero of our time.” At the Poetry Society of America, Maggie Nelson writes:

“I’ve always been fascinated, both as a feminist and a human being, in the question of where culture begins and individual humans end, especially as (human) culture is made of human beings — human beings who live in bodies, the bodies of human animals, human animals capable of making speech. Eileen has spent the past four decades plumbing these questions in poems, stories, novels, art criticism, manifestos, public performances, mentoring, journalism, teaching, and more, with more experiment, hilarity, provocation, electricity, and doggedness than any writer I know of.”

8. How to Grow Up: A Memoir, by Michelle Tea

Michelle Tea, author of Valencia and other rad things, discusses her evolution in this essay collection slash memoir. At the Rumpus, Antonia Crane writes:

“How to Grow Up is Tea’s most commercial memoir to date, because it’s a refined and polished narrative that begins with Tea in her seedy digs in the Mission as a struggling writer and ends with our fierce heroine blossoming into a woman with a successful writing career and a baby. However, How to Grow Up still contains all of Michelle Tea’s signature lust for life as she trots towards her own colorful version of adulthood, motherhood, and recovery, reminding us that there’s hope after all—even for spirited pirates who have gotten lost on the path towards maturity.”

7. Asking For It: The Alarming Rise Of Rape Culture — And What We Can Do About It, by Kate Harding

In Asking For It, Harding discusses recent issues in rape culture, including rape jokes, false reports and racism, rape kits, blame, current cases and more. In a review at the Los Angeles Times, Rebecca Carroll writes:

“The fundamentals are here — consent, politics, trolls and police accountability. But throughout, Harding offers a fluid, urgent and clear message that ends on a hopeful note. Pointing to the spike in conversations about rape on social media and in comedy series like ‘The Mindy Project,’ as well as to Emma Sulkowicz, the Columbia University student who turned her rape into a performance piece for her senior thesis by carrying a twin mattress around with her on campus, Harding writes: ‘it feels more as if a dam has finally burst. It feels as if maybe, finally, this conversation won’t taper off until sexual violence does.'”

6. Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science That Will Transform Your Sex Life, by Emily Nagoski

Research, brain science and sexuality come together in this exploration of desire and response that upends cultural ideas of normalcy. In an op-ed in the New York Times, Nagoski says:

“There is no reason to suspect that responsive or spontaneous desire is innate. In fact all desire is somewhat responsive, even when it feels spontaneous. But Dr. Heath and Sprout are both part of the long history of trying to call ‘diseased’ what is simply different.

When a woman experiencing responsive desire comes to understand how to make the most of her desire, she opens up the opportunity for greater satisfaction. Outdated science isn’t going to improve our sex lives. But embracing our differences — working with our sexuality, rather than against it — will.”

5. Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home, by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Lambda-Award-winning author Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha tells her own story in the autobiographical poetic Dirty River. In an email published on Little Red Tarot, she writes:

“What started as a desire to write ‘the brown girl’s version of Valencia‘ turned into a desire to try and write about some of the hardest times in my life, my early 20s where I ran away from home and the United States to deal with my family’s legacy of childhood sexual abuse, internalized racism and displacement from Sri Lanka. I also wanted to document late 90s queer of color, psychiatric survivor and queer punk of color community and life in Toronto, the city I love. To write a transformative justice childhood sexual abuse survival book that broke away from easy ideas of healing and was all queer, brown and weird everything.”

Bodymap, a collection of her poetry that Carmen calls “a tumultuous journey through otherhood, the fleeting things that change us, and the fights we have with ourselves in the mirror and in our heads,” came out this spring.

4. Lumberjanes Vol. 1, by Noelle Stevenson, Grace Ellis, Shannon Watters, and Brooke Allen

Lumberjanes is the story of five girls at scout camp when weird shit starts happening. There are trans and genderqueer and POC characters and people swear by taking feminist names in vain and it’s earnest and sweet. In announcing Lumberjanes as the winner of multiple categories in Autostraddle’s 2015 Comic and Sequential Art Awards, Mey wrote:

“From its very first issue, Lumberjanes has been consistently delivering a diverse, complex and fun team of girls going off on adventures and being not only great friends, but also their own heroes. This book tells all girls that they deserve to have friends, do anything they put their minds to and be whomever they want to be. Plus, it’s simply one of the most consistently fun, funny and exciting comics out there.”

* Disclosure: I’m married to Shannon Watters, and Grace Ellis used to work for Autostraddle, but I would 100% recommend this book no matter what, SO.

3. The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson

The Argonauts is a part-memoir, part-theory accounting of Nelson’s relationship and queer family building. In an interview with the Rumpus, Nelson says:

“I have had a lot of ambivalence about the idea of family life, as you say. In fact, before I met Harry, “family” was not a word I ever really used or ever wanted to use, for all the familiar feminist, queer, and collectivity-based arguments against it. What became interesting via talking to him was how comfortable he was with the term, how he used it so widely and happily. It really amazed me. He would probably say this comfort came from years and years of living in a queer subculture, so that the concept for him always meant chosen family more than the nasty, privatized, oedipalized, sanctified, heterosexist, sentimentalized, used-as-an-excuse-to-persecute-all-perverts, and/or violent nuclear family. So that has probably had a profound influence on me. In some ways it was probably the condition of possibility that has allowed me to overcome my ambivalence enough to write something that could be called ‘a book about my family,’ words that still sound somewhat foreign to my ears.”

You might also remember The Argonauts from Autostraddle Book Club #8.

2. Under the Udala Trees, by Chinelo Okparanta

In this first novel by Chinelo Okparanta, two displaced girls fall in love against the backdrop of civil war in Nigeria. The resulting coming-of-age story “reads much like American lesbian novels of the 1950s,” writes Carol Anshaw in a review in the New York Times Sunday Book Review. In an interview with the Rumpus, Okparanta says:

“The situation in Nigeria is not all that different from many places around the world. After the publication of this book, I’ve been shocked by a handful of people here in the United States who have come up to me and said things along the lines of, ‘Well, we’ve moved on from that. Same-sex marriage is now legal in the United States, so what’s the point writing that book?’ I look at the people making the statement and I can just smell the privilege wafting out of them like perfume. And, I think to myself: this is the problem with privilege. When we live in our own privileged little bubble, it is convenient to pretend that all is well with the world, that everyone enjoys the same privileges that we do. We conveniently forget that there are others, sometimes our very own next-door neighbors, who suffer in ways that we do not. I think the novel is a testament to this: a reminder that just because we perceive ourselves free does not mean that everyone is indeed free.”

1. Girl Sex 101, by Allison Moon and K.D. Diamond

Girl Sex 101 is the ultimate roadmap to girl-on-girl sex. It’s friendly, trans- and genderqueer-inclusive, depicts all sorts of bodies, is sex positive and is the number one sex book to read right now. As quoted in “9 Sex-Life-Changing Tips From ‘Girl Sex 101,’” Moon writes:

“The thing to remember is that you’re allowed to seek and have the sex you want. You are allowed to choose your partners, choose to be celibate, choose to be slutty, choose to be monogamous, and choose to have sex solo or in groups. You get to have consensual sex when you want, as often as you want, with whomever you want. That is your right as a human in this world.”

Honorable Mentions, In The Order That Made Their Covers Look Most Aesthetically Pleasing In The Below Graphic

Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Hunger Makes Me A Modern Girl: A Memoir, by Carrie Brownstein

Queer Brown Voices: Personal Narratives of Latina/o LGBT Activism, edited by Uriel Quesada, Letitia Gomez and Salvador Vidal-Ortiz

God Help The Child: A Novel, by Toni Morrison

SuperMutant Magic Academy, by Jillian Tamaki

The Paying Guests, by Sarah Waters

Nimona, by Noelle Stevenson

The Gap of Time: The Winter’s Tale Retold, by Jeanette Winterson

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings, by Shirley Jackson

The First Bad Man: A Novel, by Miranda July

9+ Queer Canadian Poets to Break Your Heart and Put It Back Together Again

Pick an arts scene, any arts scene, and you’ll find your share of queer folks there, whether lurking in the corners or sparkling onstage. As a young Canadian writer coming to terms with my sexuality, the poetry community was especially inviting. The sheer number of queer Canadian poets is amazing — in some communities, especially among women, the ratio seems close to 50%. This was the first world I spent time in where a casual mention of a girlfriend, or a suggestively Sapphic poem, was not only acceptable but normal. It was a mirror for all my confused feelings and a breath of fresh air.

Queer Canadian poets tend to be experimental, to push against boundaries. They explore questions of identity from different angles, some by examining personal and collective history, others from a theoretical or epistemological standpoint (What do we know ourselves to be? How do we know it’s true? Do we?). They tell it like it is, challenge our ways of thinking, and actively organize for change. Their words are hilarious, heartbreaking, and wise. Here are some queer Canadian poets — mostly female-identified — whose words have changed my world for the better.

1. Zoe Whittall

Zoe Whittall‘s novel Holding Still for as Long as Possible has a well-deserved shout-out on Autostraddle. But did you know that Whittall is also a wonderfully clever poet? Her collections The Best Ten Minutes of Your Life, The Emily Valentine Poems, and Precordial Thump hold a finger to the pulse of lesbian culture. I can’t help thinking that Whittall would make a great Straddler. She’s gritty, urban, socially conscious, and doesn’t shy away from writing steamy/awkward moments that ring true. Her sassy blend of smarts and pop culture is a combination many of you will appreciate. Take this tidbit from her poem “Hall Building Prose Massacre”:

“In a 1994 writing class I wrote a first-person story based on my life at the time. It was fast, flawed, inorganic and riddled with a cherubic innocence.”

Who hasn’t been there?

2. Nathanaël

Mysterious poet-translator Nathanaël (formerly Nathalie Stephens) “writes l’entre-genre,” a French term which means both between genres and between genders, in English and French. Her poems were my introduction to literary gender-bending, a revelation at the time. In Je Nathanaël she takes the persona of a literary character (André Gide’s apprentice in his prose poem “Fruits of the Earth”) as her own, crafting an alluring “queer boy” alter ego. “One body conceals another,” the book’s back matter promises, and this poet uses the idea of a there-but-not-there other to play, seduce, and question: “Who wants Nathanaël? I do I do. Only he doesn’t exist. He is not kissing you.” Nathanaël has about 20 books out now, some of which explore the different layers of city and text in much the same way she interacts with identity. It delights me that her gender-bending alter ego eventually became a permanent pen name. Some of her work is written in English, some in Frenc h, and some weaves between two languages, self-translating – making an art form out of bilingualism.

3. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha‘s gutsy poetry reveals as much as Nathanaël’s conceals. This Sri Lankan femme dynamo divides her time between Toronto and Oakland, where she’s active in community organizing. Her books Consensual Genocide, Love Cake, and Bodymap dish up real talk about reclaiming Tamil identity, surviving childhood sexual assault, fighting for social justice, and navigating the imperfect loves and not-always-safe spaces of queer community. These poems are love letters, fierce and resilient. Read one and you won’t be able to put the book down. As her voice grabs you, it imparts revelations:

“There are children who learn to fly young. Winging when Bad Things Happen, they have powers of escape, going out the top of their skull when life gets stupid.”

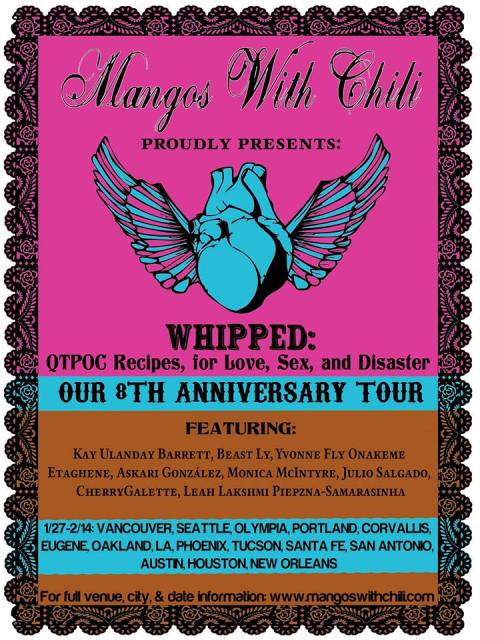

Another gem is her take on young femmes performing beauty by glamming up and walking around town, “practising choosing who or no one to let touch them” — an act she dignifies as “doing hard work.” Between co-founding a touring cabaret of queer and trans artists of color, Mangos with Chili, and Toronto’s Asian Arts Freedom School, performing for Sins Invalid, and fundraising for Black Lives Matter through community healing spaces in 2014, her hard work is everywhere these days.

4. Sina Queyras

Poet-critic Sina Queyras is an all-around badass. Her debut collection Slip is a sonnet sequence that chronicles a lesbian romance. But Queyras really hits her stride in later books like Lemon Hound, Expressway, and MxT. Straddling the line between lyric and experimental, these daring poems draw from Virginia Woolf’s novels, William Blake’s Memorable Fancies, Google’s traffic accident reports and Dorothy Wordsworth’s diaries. Their verve is all Queyras’ own:

“Yes I have hiked in the Laurentians. Yes, yes, yes I can find my way home. Yes with a zucchini. Yes with a water gun shaped like an eggplant.”

Queyras liked her Lemon Hound persona so much that this “feminist flaneur” became the curator and title of her online magazine. Lemon Hound (the magazine) showcases new work while calling for mutual respect between poetry’s disparate movements and increased involvement from women in literary criticism.

5. Dionne Brand

Dionne Brand is a novelist, essayist, former Toronto Poet Laureate, and one of Canada’s most prominent poets. I love that a Black lesbian occupies that space. Her 18 books expose hard truths about the Caribbean diaspora’s experience of exile, racism, gender inequality, and other forms of oppression lurking beneath Canada’s peaceful facade. Her language sings through the pain as a way of calling it out. In Land to Light On, she portrays Canada’s weather and politics are equally hostile; any peace she finds in exile there “is getting used to harm.” Her essay “This Body for Itself” critiques literary representations of Black women that avoid their sexuality, and makes an argument relevant to your interests:

“The most radical strategy of the female body for itself is the lesbian body confessing all the desire and fascination for itself.”

Her long poem thirsty will, sadly, strike a chord with modern readers. It deals with a police shooting of a Jamaican-Canadian man in 1980, who died whispering “thirsty,” and the murder’s ripple effect on his family and city. She asks, “would I have had a different life / failing this embrace with broken things, / iridescent veins, ecstatic bullets, small cracks / in the brain”?

6. Erin Moure

Erin Moure writes in an avant-garde vein. Like Nathanaël, she’s a translator who crafts multiple identities. Elisa Sampedrin, a mysterious figure with a different biography than Moure’s, makes her first appearance in Little Theatres as the author of a portion of the text. In O Resplandor, she translates Romanian poet Nichita Stănescu and leaves a trail of clues — a photo, jottings “fallen from a notebook… and caught on the heel of a shoe” — for the narrator, to follow. Prose poems narrating this treasure hunt interweave with poems and translations by both poets. Sampedrin has truly taken on a life of her own, popping up as the author, translator, and creator of other texts. “When I told people I’d invented her,” says Moure in an interview, “someone in the audience disagreed vehemently and told me that she’s making films now.” Moure is interested in language as resistance, breaking up lines and inserting letters that don’t signify anyt hing concrete, or inserting Galician words into English sentences. They may not mean something to the reader, she argues, but they’re an act of resistance against the English language of rhetoric and war, one that gestures towards something beautiful.

7. Trish Salah

I’ve had the privilege of reading alongside Trish Salah, whose debut, Wanting in Arabic, seeks to piece together individual (trans femme) and collective (Arabic) identities from fragments.

A change of sex is not a suicide note.

What is a crypt?

She heard him with his word.

Veiled, crossed out, divide of his mouth still open.

She made her up–a language–we can only imagine

What does it mean to be Arabic when your ancestors’ lands are at war, you’ve never been to Lebanon, and you don’t speak your “father’s tongue”? Salah’s poems are lovely dialectics, sometimes weaving together two different voices on the right and left sides of the page. An early and instrumental trans scholar, Salah is equally at home with feminist theory and lush, kinky carnality. Her poetic voice is wise and ripe with beauty.

8. Rita Wong

Rita Wong is another writer intent on reclamation. Her first book monkeypuzzle is a lyrical examination of Chinese-Canadian identity. Like Piepzna-Samarasinha, she writes about the importance of claiming her native tongue while living in a country where it’s marginalized:

this bittersweet taste:

words we no longer have

replaced by ones we no longer want

She enacts this beautifully by integrating Chinese words into some of monkeypuzzle’s poems. In her second book, forage, her poetic concerns shift from the personal to the ecological, especially genetic modification, which she considers an experiment performed on us that we didn’t consent to. Her current poetic project is focused on water, and is bound to be amazing.

9. Susan Holbrook

“Funny” isn’t the first word I associate with poetry, but Susan Holbrook‘s Oulipo tampon poem had the audience in stitches at a Montreal reading. In “misled” she writes about the common childhood occurrence of misunderstanding words — “and ‘laurels.’ what else could they have been, and what else could they be, except buttocks, what else but butts. we were supposed to look down on people who ‘rested on their laurels.'” Her second book, Joy Is So Exhausting, includes a unique take on motherhood — a long poem made up of lines written while nursing. It also features her howler of a tampon poem, which replaces certain words in a set of tampon instructions with nearby terms chosen from the dictionary:

“Your First Timpani? Take a deep Brecht and relapse. It’s much easier to insult a tanager when you’re religious.”

Holbrook’s gentle humor creates a climate where poet and reader can laugh at themselves together, even as emotionally weighted lines, like “the tomboy should now be comfortably inside you,” are woven in. As she says in an interview, “I can get away with more feminist and queer critique if an audience is giggling.”

There are many other queer Canadian poets worth reading, so I’ll mention some of them briefly. Rachel Zolf has an affecting collection on Israel-Palestine warfare and a crowdsourced book called The Tolerance Project. It was created when Zolf registered for an MFA in order to follow her partner to the US, since their relationship wasn’t legally recognized there, and it does a great job of exposing the absurdity of this situation. Larissa Lai, who’s collaborated with Rita Wong, has some interesting takes on the relationship between technology and humanity. Sarah Dowling writes sensual fragments that make good use of spaces on the page. Dani Couture is a master of the edgy lyric. Margaret Christakos splices together bisexuality and motherhood in unsettling ways. Scottish-Canadian Sandra Alland does amazing work with sound poetry, and T.L. Cowan has great performance poetry out there. Then there are the classics: influential feminists Daphne Marlatt, Di Brandt, and French-Canadian Nicole Brossard, whose books are available in translation.

I hope you enjoy checking out some of these poets’ incredible work. If you have any favorites you’d like to add to the list, I’d love to hear about them in the comments!

Read A F*cking Book Review: Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is Living Her Truths in “Bodymap”

we’ve always come on boats. we’re going to keep coming. we know the waves and rough water. / bless the rough water and the small boats. / bless the worst thing.

Lambda Award winner Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book of poetry, Bodymap, covers a lot of terrain. All of it is personal, all of it is raw, all of it keeps you turning the pages and makes your heart beat and wither and burst.

It’s a tumultuous journey through otherhood, the fleeting things that change us, and the fights we have with ourselves in the mirror and in our heads. Leah’s a powerful guide, armed to the teeth with confessions, a steadfast sense of humanity, and a killer optimism. Bodymap is the winding tale of a 30-something’s journey in this world, one centered around her experiences as a queer, disabled femme of color from working-class roots and with a legacy in diaspora.

The title poem is about love and how it changes us, how it helps us erase and redirect the past and our emotions and maybe even the things that make us tense or anxious or uncomfortable. Throughout the book, Leah’s searching for salvation — by laying in bed with her vibrator, fucking in bathrooms, driving a beat-up car across the bridge, or clinging tightly to the people who show her themselves and a little bit about herself in the process.

The poems cover a lot of ground, but they never lose the unwavering voice. They never lose the strength, the drive, the relentless pushing and scraping and grasping for more. Leah’s activist spirit and tender queer heart fill the pages, every one. It didn’t hurt that I saw so much of myself in the book, hidden inside the dirty bar bathrooms and in love on someone’s couch. But the way Leah writes let me see her, too, in all of her glory and splendor and low points. Her poems go where other poems so often can’t or won’t, past watching Netflix all night because of fibro and the people who can’t love us like we need to be loved and forgiving ourselves for how we treated our parents and how delicious freedom tastes even when it’s hard to swallow and hard-fought.

It can be easy to obscure yourself in poetry, to hide your own ugly or to write so many lines about how much you loved your kindred spirits and all of their faults until you run out of room to talk about the other stuff you’re carrying across borders. But Leah doesn’t.

This is all of it, all the guts and all the hurt and all the days she lusted to leave her office or to go home or to get out of bed.

I gave myself one week to read Bodymap. It didn’t even take me three days, each one spent waiting until the commute to and from work to tear into it and read and reread the poems on the train until I missed my stop or felt a little less alone in this world. There’s something about the kinds of stories that acknowledge the desolation and the hopelessness but refuse to forget the amazing stuff we do in spite of it, or in the thick of it.

I told myself 2015 was the year of living my truths. I’m excited to have a guide in this book, and in Leah’s soulful mission to love and be loved — the rest of it be damned.

Happy International Fisting Day! Here’s Some Willfully Misinterpreted Lesbian Poetry

Feature image by Nomy Lamm via the fisting day tumblr.

Today is International Fisting Day! A day for spreading the joy and knowledge of fisting throughout the internet so those who aren’t familiar with it can learn and those who are can fist bump.

Jiz Lee, one of the people who started International Fisting Day in 2011, writes about why fisting isn’t scary, why everyone should try it and why it’s just amazing:

“What I love about fisting someone vaginally (or through their front hole, if they don’t associate with the v-word) is feeling them TAKE ME IN. There’s a moment where the person just opens up to you. Once inside, they’re warm, wet, and every little movement you make can be felt. It’s something that may take time. Fisting is something that doesn’t necessarily happen right away. You put a finger in. Then two. Then three, four, and then… and sometimes after long and gentle coaxing, the thumb. Sometimes lovers can try several times in sex before fisting happens. But once you’re in, it’s golden! You can angle your hand for G-Spot stimulation. You can find your lovers’ ‘A Spot,’ which is just under the cervix towards the back. Some like to feel a bit of pressure there. You can carefully stroke and ‘jerk-off’ the cervix, as if it were a small, internal cock. Unlike using a strap-on or dildo toy, my hand can feel every motion. It’s incredibly intimate and really sexy. If the chemistry and connection with my partner is strong, I can come from penetrating with my hand!

As someone who loves to receive a fist, I enjoy an unparalleled feeling of fullness. The most sensitive areas of the vagina are just within the first few inches inside. I like to use my kegel and pelvic muscles to grip snugly around a lovers’ wrist, which can be compared to the girth of a medium-large dildo. Deeper inside, pressure feels really good for me. […] Combining clitoral and vaginal stimulation, the network of nerves and contracting of muscles orchestrate some of the most amazingly intense orgasms I’ve ever had.”

In the past, we’ve written about five fisting tips, published a cool infographic and fisting love story and generally shared resources, but there are only so many ways to say “lube up and make your hand look like you’re reaching into a Pringles can very, very gently” so this time we’re celebrating fisting through pure poetry.*

*I may be willfully misreading and decontextualizing some of the following poems and excerpts so that they are more relevant to actual fisting as opposed to receiving love or four fingers but no thumb or whatever.

“#184” by Anna Pulley

Why you should be proud

to have small hands: sewing,

picking your teeth, fisting.

“this is what it looks like when it finally comes” by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

I open under her hand

wider than I ever have

and there’s no clenched fist vulva, no bleeding,

no little welts rising up on my labia saying no

I open to her fist like the biggest cracked grin

bigger than anything I’ve known how to know

“Love Poem to a Butch Woman” by Deborah A. Miranda

Sweetheart, this is how it is:

when you emerge from the bedroom

in a clean cotton shirt, sleeves pushed back

over forearms, scented with cologne

from an amber bottle—I want to open

my heart, the brightest aching slit

of my soul, receive your pearl.

I watch your hands, wait for the sign

that means you’ll touch me,

open me, fill me; wait for that moment

when your desire leaps inside me.

“The Aureole” by Nikky Finney

The stars over the Atlantic are dangling

salt crystals. The room at the Seashell Inn is

$20 a night; special winter off-season rate.

No one else here but us and the night clerk,

five floors below, alone with his cherished

stack of Spiderman. My lips are red snails

in a primal search for every constellation

hiding in the sky of your body. My hand

waits for permission, for my life to agree

to be changed, forever.

“The Dream” by Aphra Behn

The soft resistance did betray the grant,

While I pressed on the heaven of my desires;

Her rising breasts with nimbler motions pant;

Her dying eyes assume new fires.

Now to the height of languishment she grows,

And still her looks new charms put on;

Now the last mystery of Love she knows,

We sigh, and kiss: I waked, and all was done.

“Dear Andrea” by Eileen Myles

I love you too

don’t fuck up my hair

I can’t believe

you almost

fisted me

today.

That was great.

Fool’s Journey: Radical Tarot Reader Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha Is Anything But Cranky

The tarot community is filled with amazing people, all working with their cards in different ways… some as artists, some as healers, some as activists, historians, storytellers, or philosophers. Today, I am so excited to introduce you to a tarot reader I’ve long admired. Writer, performer, activist and tarotist Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha of Brownstargirl Tarot has been reading the cards for twenty years, combining intersectional politics, community organising and radical folk healing in the most incredible ways. When I first found out I was gonna be writing this column for Autostraddle, the first thing I did was email to ask for a little of her time.

I mean, could you honestly resist a reading from this person?

Cranky, compassionate intuitive counselling by a queer, cis femme of color with a chronic illness and a brokeass background who understands systemic oppression.

[…] My mom raised me to know that listening deeply was just another thing that people could do, and comes from a tradition of tough ladies who survived by their sixth sense.

She had me at ‘cranky’ and as I read through her website it just kept getting better. I was secretly hoping that I might be able to ask Leah to fling a few cards my way during our interview time. As it happens, Leah had so much to share with me, so much wisdom and compassion and philosophy, so many years of experience in seeing how tarot and intuitive counselling can empower marginalised communities… that we ran out of time for anything like that.

Leah talks fast and our interview was an hour long — please know that this article cannot possibly do justice at all to her impassioned ideas and thoughtful, joyful storytelling.

We started off discussing how she first starting using tarot in her daily life.

The way I got into tarot was… well, I was 19 years old and honestly? I was this young, queer, survivor of colour who was just finding herself and I had just got a scholarship and moved to the middle of New York in the early ’90s… and I was having a really hard time. My mother had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, I had finally left home after waiting my whole life to escape a family situation which was like… complicated and great and abusive… the girl who was my first girlfriend who I was madly in love with was suicidal and I was like… “Wow! I’m having a really rough time!” And I was just in the middle of that really white riot grrrl scene and a really straight students-of-colour activist scene, where everything was supposed to be, you know, really fun, I was just struggling and feeling really isolated and dealing with all of these really heavy things.

And I got my first tarot deck that year — I spent a lot of time going to bookstores, you know, in New York there were all these bookstores that stayed open all night, and I would just have this circuit where I would go around and read standing up in the bookstores because I couldn’t afford to buy the books, and I started reading [tarot veteran] Mary Greer, and developing my understanding of tarot and also numerology, and it was just so comforting. I could see that I was having like ‘a Hanged Man year’ or ‘a Death year’ or that I was totally the High Priestess at that time, and so on, and everything really just started to make sense. Like, this wasn’t just a bunch of random shit just coming at me — there was a whole story happening, and this whole system of archetypes that I could draw on, and I can also see that this is me as being part of a story that I’m in, and I have choices, and I can work through these challenges, you know?

So I started reading for myself, and in the middle of feeling like this really wackadoo, isolated, depressive person, it was really comforting to be on my own and be like this witchy, mystical individual person. And I would go to the park and read my cards and give myself this kind of counselling that was also really accessible and affordable to me.

As well as reading tarot, Leah is an active community organiser, involved in a whole range of radical social justice projects, such as Mangos with Chili (‘the floating cabaret of queer and trans people of color bliss…’), the Bad Ass Visionary Healers, and so many other organisations that I just couldn’t scribble down fast enough.

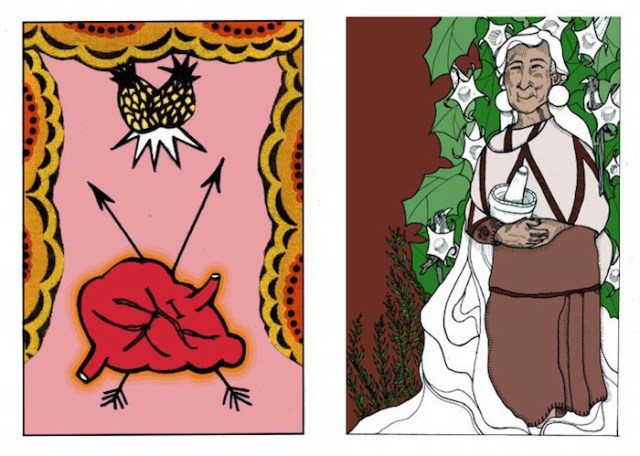

Artwork by Millan Figeroa

I was interested in the intersection between Leah’s spirituality and her politics, and we talked a lot about how Leah’s approach to tarot and the ways in which her intuitive tarot practice informs and supports — and actually, is integral to — her activism.

It all really makes sense for me, because you know I’m a writer and a performer and a curator and also a community organiser, and for a lot of people doing conventional activism it can feel like the witchy, spiritual, healer worlds are completely in a different room from being a creative person, or being an organiser, and I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how connected they are… and that makes me think about one of the organising principles of the Allied Media Conference (which is this progressive feminists-of-color media conference I do a lot of organising with) which is ‘we begin by listening’.

One thing we’re doing within this activism is this focus on building, rather than on reacting, and on our own power as oppressed people to create our own amazing solutions… and two years ago when I started thinking “right, I’m gonna do this tarot thing as an actual business,” those worlds really started coming together, and I actually got them tattooed on my arm.

It really made me think about how the way that I approach all of those things is by really listening to people where they’re at, whether that’s a client asking me what the fuck is going on, or if it’s in the healing justice and transformative justice work that I’ve done… again, it’s a process of really paying attention to what’s really going on in our communities and really listening. And also when my co-director and I were rethinking how we describe Mangos with Chili, we were talking about how we really think of what we do as creating a healing space which is really deeply spiritual. So for example each year we do this show called ‘Beloved’ which is focused on our queer and trans people of color ancestors and people we’ve lost to hate crimes and violence, and like, we didn’t even think about it, it was like “of course we set up this giant altar every year!” but of course not every performance artist does that.

I guess for me, there’s this thing of – after my own experiences when I was 19 and isolated and depressed and finding myself through the tarot and now twenty years later – using tarot as a tool with oppressed people and communities, and thinking of it as a way for us to collectively get clarity and figure out situations that are really painful and complicated, and just to cut through the bullshit. And so it really is this process of just deeply deeply listening and paying attention to what’s really going on. Because of course as oppressed people, a lot of the time we’re taught that our bodies and our intuition are not to be trusted and that we should just go work our jobs and do what the powers that be tell us to do, and so I really believe that it’s a deeply revolutionary act to work with our intuition and to work with what we know.

And also you know for so many communities of color, using our spirituality and intuition has always been part of our revolutionary practice — I mean, spirituality and religion can of course be used to oppress, but in so many cultures these practices have given us so much strength, and then obviously in turn have been ripped off by this very white, western idea of spirituality.

So our spirituality and our politics aren’t necessarily separate, you know? And that’s why I don’t really see my tarot practice as this silly thing, or this party trick – it’s so important to my work with communities.

So, of course I wanted to know, what was that very first tarot deck you picked up in the all-night bookstore in NYC twenty years ago? And what about the decks you read with now – how do they inform your practice?

The very first tarot deck that I got was the the Daughters of the Moon Tarot, which is this very 80s-feminist round deck, and there are lots of women of colour in it.

Although I’m pretty critical of a lot of this stuff, I’m also really grateful to the 70s feminist spirituality movement for this idea that we can re-imagine tarot — like, these things are all archetypes, but they don’t have to be drawn in these ‘white, boy-gets-the-girl, female-negative, male-positive’ ways — we can re-imagine tarot in ways that work for us. And though I don’t necessarily agree with every interpretation of every goddess in that particular deck and so on, when I was 19 it was just really what I needed. So it really shaped my understanding that I didn’t have to like walk around this very white non-intersectional narrative of tarot, I can have my own relationship with these archetypes, and for years it was the best deck that I’ve found.

And besides, tarot’s origins are from Romany people — people of colour — and it’s really funny to me that when think of tarot these days we’re imagining those Rider Waite cards, you know, there’s a guy in a robe and all these knights and kings and queens and so on, and I feel like in my own tarot practice, I’m always reaching for before that.

And what I do with the cards and in a reading is that I don’t just sit down and go “okay this is what the book says,” I’m bringing my own way of looking at each card, and using my own intuition, and being in touch with the energy of the person I’m sitting with, and my own relationship with my own spirituality, and it’ like ‘okay in this moment, with you.

The deck I read with most of the time now is the Collective Tarot, and I’m just really grateful for those cards. It’s just so great to have a deck that is black and brown and has people with disabilities and queer folks and gender non confirming folks, and it’s also like a living document, you know? And although it’s out of print and they’re probably not gonna make another one, I feel really excited that there might be other radical tarot decks that come out… for example I’d love to see a black feminist tarot deck, and I’d love to see an indigenous tarot deck… there are so many different ways that we can interpret these cards.

Leah shared these two images from the Collective Tarot – The Lovers and The High Priestess

We have personal and collective power, you know I don’t believe that the future is like already written — that would be terrifying, right?! So when I was writing up my website, and focusing on this way that I really think tarot can be political and is political, it was important to me to get across the idea that we create the future with our choices, and keep coming back to this idea that even though there are these systems that oppress us, and even though we also don’t control life — the house collapses or a partner leaves us or we suddenly have a different relationship with our bodies… still, we have choices. We’re all such magical beings! It’s like ‘I am not just this person that fucked-up shit is happening to – I’m a hero, on a journey!’, and tarot helps us to actually tell that story and say ‘look — here’s you, and here’s the stuff that’s going on around you, and look, here are some choices!’

One thing all tarot readers have to deal with sooner or later is this issue of boundaries. I mentioned how I personally prefer not to read for people in my immediate community, simply because for me that crosses a personal boundary — and asked Leah about where her own boundaries lay and how she maintains them.

Yeah right! Because you know, most of the people I read for are maybe one or two degrees of separation from me, so it can be hard right in the middle of this community, being the tarot reader. And if I really had to pick a central community that is closest to my heart, of all the communities I read for, it would be the queer femmes of color, those are the people I feel the closest to, that I love so much, and so there it’s like no degrees of separation! So maintaining those really strong, clear boundaries really is this big thing. But with the tarot, and also going back to my days working as a rape counsellor, and then moving into work doing transformative justice in communities of color, I basically feel like I have this external hard drive with everyone’s stories, which just go into the vault.

I do have really firm boundaries, but it can be like this catch-22 situation where I really want to read for people who are working in these particular marginalised communities. It’s something I can give, something that has value. Because one thing I’ve come to see, especially in the past couple of years, is that people really need these spaces where they can come and talk about what’s really going on, and not be worried that I’m gonna be fat-phobic, or racist, or look down on them because they have a disability or something with their mental health. And as someone who has identified as ‘crazy’ and as a survivor myself, and as someone who has walked between worlds, I really get that need to have a space to deal with this stuff that is spiritual, not clinical, and that’s something I really feel I can offer to people. It’s something that just doesn’t exist so much in the mainstream mental health services, where it tends to be more like western talk therapy, which is like “okay, talk to me once a week”, and that’s it.

So providing this spiritual space where people can work through their stuff, I feel like that’s something I can offer to people. I use my intuition with these cards, I’m using my spirituality, I pray before I work with you, we do some breathing and somatic exercises to ground us, I ask my ancestors and the land we’re on for assistance in helping to give you a reading that is useful, and then we can really just sit together and be in this ‘okay, tell me everything that’s going on’ place. It’s political because it’s an accessible form of healing, that brings in spirituality, that brings in ancestry, and that can cut the shit a little bit, right? With the cards I can be like ‘okay, so this is what the cards are showing me, does this ring a bell?’ and so many people are like ‘holy shit, this isn’t just something crazy that’s happening to me, I can see it more clearly now, and I can see my challenge and see my choices.’

It really took me a while to come out of the broom closet and be like ‘yeah, I’m a healer, and the way that I heal is I’m an intuitive healer, and this is something that’s really of interest and use to the community’, and really it took me so many years… recently I was at Safetyfest (which is organised by Communities United Against Violence, a queer and trans anti-violence organisation) where there was performance and workshops and all this stuff about how we can create more safe spaces within our communities and they were offering free healing to all the people that were there, and I was able to offer tarot… and it felt so amazing to be sitting there next to someone who was offering herbal therapy next to somebody who was offering somatic therapy next to somebody who was doing reiki and acupuncture and offering it for free to all these queer and trans folks… and I really feel right now like there’s a new wave right now of folks who are tarot readers and intuitives and herbalists who are coming out of the healing justice movement right now and it’s a real change from even like six years ago when it felt like I really only knew only one other person who was queer and offering this stuff…

It’s been so amazing to see so many people who are able to articulate that intuitive counselling and these types of healing are really of benefit to our communities. And I’m really influenced by this idea that divorcing health and healing from our work is actually not a way of making the work more efficient… and I’m thinking now about this article ‘Communities of Care’ I read a couple of years back by [queer femme yoga teacher] Yashna Maya Padamsee — she was making the point that we talk about self care as if, like, ‘we work 80 hours a week and then we take a bubble bath,’ but what would it be like if we actually changed our whole movements, so there’s food at every meeting, there’s health care at every meeting, we ask each other how we’re doing, there’s flexibility, as in, ‘you’re freaking out today? Well you take a day off and I’ll handle this, and you’ll take over when I’m freaking out!’ And I really feel like this this way of thinking about healing justice has really informed the way that I do tarot.

To round off our interview, I asked Leah for the three personal qualities she feels makes her a great tarot reader.

Oh wow. Well — I’m totally non-judgemental. There’s nothing you can say to me that I’m actually going to shame you for.

The intersectionality — you know, my tag line is ‘snarky, compassionate intuitive counselling by a queer, cis femme of color with a chronic illness and a brokeass background who understands systemic oppression’ — and when people go to therapists and they’re thinking ‘oh my gosh, is she gonna get that I’m poly, or my whole Mexican family,’ or whatever, and it’s like, I can’t promise to get everything, but you’re not neccessarily going to have to explain all of the things to me.

And compassion — I have a deep compassion for the people that I work with and when people say thank you, I say no, thank you, because I feel like we’re actually healing together, it’s not a one-sided experience. I feel so respectful of my clients as they’re coming into their power… you know, we’re all human beings in these crazy situations together, and our struggles, and how we’re trying to figure it all out together the best way that we can. So yeah — big respect, and so much compassion.

If you wanna know more about Leah, her tarot, her art and so much more, you can catch up with her at her tarot website, brownstargirltarot.wordpress.com, and at her bog, brownstargirl.org.