Monday Roundtable: Our Favorite LGBTQ Historical Figures

It’s LGBTQ History Month, and not a moment too soon! It’s absolutely necessary at this moment in time to remember some of the icons of our collective queer past who have overcome all kinds of adversity to change the world and our individual lives. So we’re dedicating this first roundtable of October to our favorite LGBTQ historical figures.

Billie Jean King

Heather Hogan: I love LGBTQ+ history because LGBTQ+ people have done so many of the best things in this world! It’s hard to choose a favorite; I want to list 100 queer women! I’m going to go with my love, my love, my love Billie Jean King, though. She is, of course, most known for winning the Battle of the Sexes against Bobby Riggs in 1973, on the heels of founding the WTA, which she established, played in, and maintained, all because she refused to accept that women tennis players deserved less money than their male counterparts. Both founding that organization and agreeing to play Riggs were huge risks to BJK herself, and they were huge risks to the feminist movement at large, which she knew. She shouldered that burden with a smile!

It took BJK a long time to come out. Part of it was that she knew her sexuality would hurt the women’s movement and women’s sports; part of it was that she would lose the ability to support herself financially (which she was proven correct about: when she was outed, she lost all her endorsements in a single day); part of it was that she’d grown up with a mother who was absolutely opposed to gayness in every way. When she finally did come out, though, she became a champion for LGBTQ equality and has continued to champion women’s tennis and call out sexism in every nook and cranny of the game. Most recently in this summer’s U.S. Open when Serena faced such sexism and racism from the chair ump. BJK is one of the best tennis players in history, and also she’s just a rad-as-hell badass and very good person. And she has never apologized once for her greatness.

James Baldwin

Rachel Kincaid: My favorite LGBTQ historical figure is also my favorite writer is also my idol — longtime readers will probably be sick of me talking about James Baldwin by now but that’s too bad, here we are! Baldwin was born in 1924 in Harlem, where he was raised by his mother and preacher stepfather, and later became a junior minister/child preacher in the Pentecostal church. He left the US at the tender age of 24 to make a life for himself in Paris, finding the weight of American racism was unbearable. His writing career began to take off in Paris, and his second novel, Giovanni’s Room, was his first to deal explicitly with a same-sex relationship. His publisher at the time at Knopf told him:

…I was “a Negro writer” and that I reached “a certain audience.” “So,” they told me, “you cannot afford to alienate that audience. This new book will ruin your career because you’re not writing about the same things and in the same manner as you were before and we won’t publish this book as a favor to you… So I told them, “Fuck you.”

(This was in 1956!) Later, Baldwin left Paris, feeling an obligation to be more involved in the US civil rights movement (although it should be noted he didn’t sign on to the term ‘civil rights movement,’ calling it instead in 1979 “the latest slave rebellion.”). He wrote journalism and essays, including book-length ones like the incomparable The Fire Next Time, which reads just as urgently today. He also made public appearances for speeches, interviews and debates, demonstrating an incandescent speaking presence and rhetorical style that put all his experience from the pulpit to a different purpose. This brief debate on the Dick Cavett show about, essentially, “why it always has to be a race thing” is a good example.

Baldwin did all this while being out and unapologetically not-straight (although he refused to identify with a specific label right up through the end of his life, stating in his last interview, “The word gay has always rubbed me the wrong way. I never understood exactly what is meant by it. I don’t want to sound distant or patronizing because I don’t really feel that. I simply feel it’s a world that has little to do with me, with where I did my growing up. I was never at home in it.”) His openness about his sexuality was often a source of frustration for his allies and enemies alike, but choosing to embody a seeming contradiction was everything that made Baldwin so remarkable. He could be scathing in his cultural critiques and observations, but generous enough to give them; he was clear-eyed and unsentimental about the incredible harm he saw enacted but refused to become cynical in the face of it; he largely denounced the church he had grown up in but in many ways manifested its most admirable principles with his life and work. I love him and his work very much, and think there is an endless amount to learn from him!

Adah Isaacs Menken

Creatrix Tiara: Adah Isaacs Menken was basically Lady Gaga before Lady Gaga’s grandmother was even born. She rose to fame in the mid 1800s via her role in the play Mazeppa, where she put on a flesh bodysuit and rose a horse on stage – both very, very unusual for women at the time. (Burlesque owes a lot to this woman.) She would craft and sell photo portraits of herself to make sure people remembered her the way she wanted to be remembered. She wrote tons of poetry and essays and also had male and female lovers. My favourite part of her story is that she’d never have a consistent answer to questions about her heritage; as someone who hates “where are you from?” with a passion because nobody believes me, I’m often tempted to take on her strategy.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Carrie Wade: Eleanor Roosevelt! Her not-straightness is pretty well established at this point, but for those of you just joining the party, she had a — shall we say — close relationship with Associated Press reporter Lorena Hickok, who lived in the White House at Eleanor’s invitation (!) from 1941 until 1945. Kayla brilliantly recapped their letters to each other on this very website if you’re curious.

Of course, Eleanor stands out even among the most badass American First Ladies. Lots of contemporaries took issue with her being too outspoken, publicly disagreeing with some of her husband’s policies, and taking a progressive-for-the-time stance on racial justice. She didn’t let the bastards get her down and became the first First Lady to hold individual press conferences, write regular newspaper and magazine columns, host her own weekly radio show, and speak at a national political party convention. She was also the only woman appointed to the first American delegation to the UN.

Fun fact: the FDR Memorial in DC includes statues of both Franklin and Eleanor, but never shows them together. (Eleanor’s sits in front of the UN seal and refers to her specifically as “Eleanor Roosevelt: First United States Delegate to the United Nations.”)

Whitney Houston

Erin Sullivan: I mean, I’m not sure you would classify her as a historical figure per se, as she was just one of the biggest stars of all time, but Whitney Houston is my bi queen. She deserved so much more than what she ultimately got, in so many arenas of her life, and we really didn’t deserve her! A lot of people either a) do not subscribe to the family/assistant confirmed fact about Whitney that she was romantically involved with her friend/assistant Robyn Crawford or b) haven’t even heard about this family/assistant confirmed fact about Whitney that she was romantically involved with her friend/assistant Robyn Crawford, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true! She wasn’t out, maybe not even to herself, so there wasn’t necessarily an activist or political bent to her, but she’s a good reminder that queer people have always been out here!

Unrelated to a LGBT history, one of my favorite things that I learned in the most recent Whitney documentary was that her performance of the “Star Spangled Banner” in 1991 where everyone lost their minds was that someone tried to send her the orchestra music two weeks in advance so she could get a feel for it, and the day before she was set to sing listened to it for first time for like 30 seconds, didn’t practice, and the next day just walked out, sang it, one time, bloop, record it. Bi-excellence.

Langston Hughes

Alexis Smithers: I’m going down memory lane with these apparently but let me tell you about my home boy, Langston Hughes. We all know him, famous gay black poet one of the best writers from the Harlem Renaissance one of the best writers period BUT YOU DON’T KNOW that I’ve been obsessed with him since I was in third grade and my mom got me this picture book called Visiting Langston about this little black girl that visited Langston Hughes’ house and wanted to be a writer and my mom wrote me a note in the cover of the book telling me how much she loved me and the writing I did. I still, to this day, will flat out cry at the memory of it.

We had to dress up/act as poets for my senior class and everyone in the English department literally begged me not to do Langston Hughes (but I waited ’til the last minute so I worked with my boy anyways and I got to argue with Sylvia Plath; it was a good day).

My mom bought me all kinds of copies of his work but the one that sealed the deal for me was his entire work of collected poems. I’m looking at it right now and it weighs so much; I carried it with me when I got Saturday detention for skipping class ’cause I thought it would help me not cry for getting in trouble. I scribbled in the margins of my notebook and memorized “I, Too” whenever white people were too much which is often and I reread and recited the small poem “Suicide Note” over and over my junior year and performed my first feature across a painting of Langston at Busboys and Poets and wrote my first poems after Langston. I know there’s so much he’s done. I get overwhelmed even thinking about trying to tell you in this space. But sometimes, hearing how special other people have been to people I care about makes me want to look them up and that’s what I did here and can you tell I never did very well on school assignments.

Amelia Earhart

Alaina Monts: My favorite LGBTQ+ historical figure is Amelia Earhart. She was “close friends” with Eleanor Roosevelt, and flew for long distances with a woman-led flight crew. She married a man for convenience and had a strong jawline. She looked great in pants. She has a “steal your girl” smile. I bet her hands were soft. I watched this Netflix documentary about her last year and it definitely convinced me that her plane did not crash but landed safely on an island where she and her lover lived happily ever after.

Sally Ride

Alyssa Andrews: The idea of a “historical” figure feels like my pick should be plucked from the deep vault, but after (admittedly way too much) mulling, I keep circling back to Sally Ride: conqueror of earth, space, and a queer romantic partnership that stood the test of time. Sally changed the course of history on June 18, 1983 when she flew on the space shuttle Challenger becoming not only the first American woman to go to space, but the first acknowledged* gay astronaut (though, of course, we found that out later). If that’s not the epitome of badass, i don’t really know what is.

P.S. She’s also got a sister named Bear Ride, who’s a gay Presbyterian Minister.

P.S.S. You read that correctly. Her name is BEAR. FUCKING. RIDE.

NASA focused sources still often completely ignore mentioning anything about her queerness in any and all biographies, but she’s really google-able, and this news article is pretty sweet.

Barbara Chirlane Jordan

Natalie Duggins: I’ve been thinking a lot about my favorite LGBTQ history figure, Barbara Chirlane Jordan, recently. She was a the lawyer, educator, politician and activist, who found so many ways to etch her name into the history books. She was the third black woman to earn a license to practice law in Texas (1959). She was the first black woman elected to the Texas legislature (1966). She was the first black woman elected to represent the South in Congress (1972) and the first black woman to serve as Keynote Speaker of the Democratic National Convention (1976). But I’ve been thinking of Jordan’s role as a member of the House Judiciary committee (1974), the starting place for impeachment proceedings of federal officers.

Jordan sat on that committee, as an inquisitor, prepared to investigate whether the transgressions of a president had risen to the level of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” She proclaimed, “my faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution,” and then went on to lay out the case for Richard Nixon’s impeachment, piece by piece. She’d strengthen her argument using the words and documents of our Nation’s founders — the same documents that never intended for Barbara Chirlane Jordan to have a seat at that table — to bring down the President.

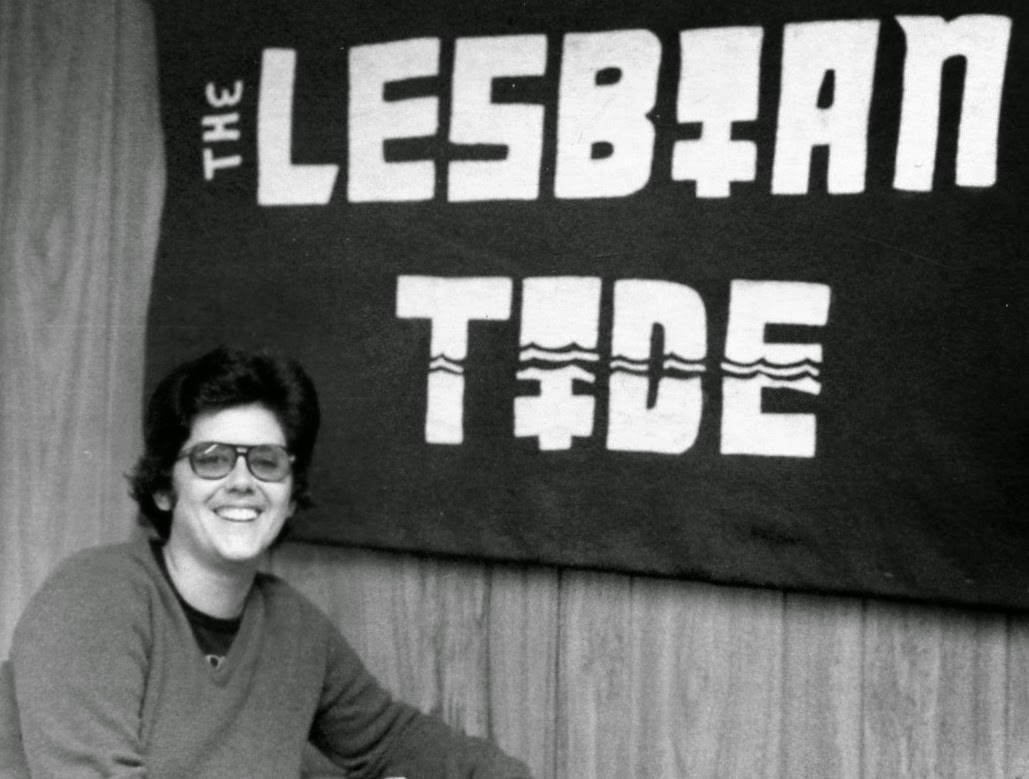

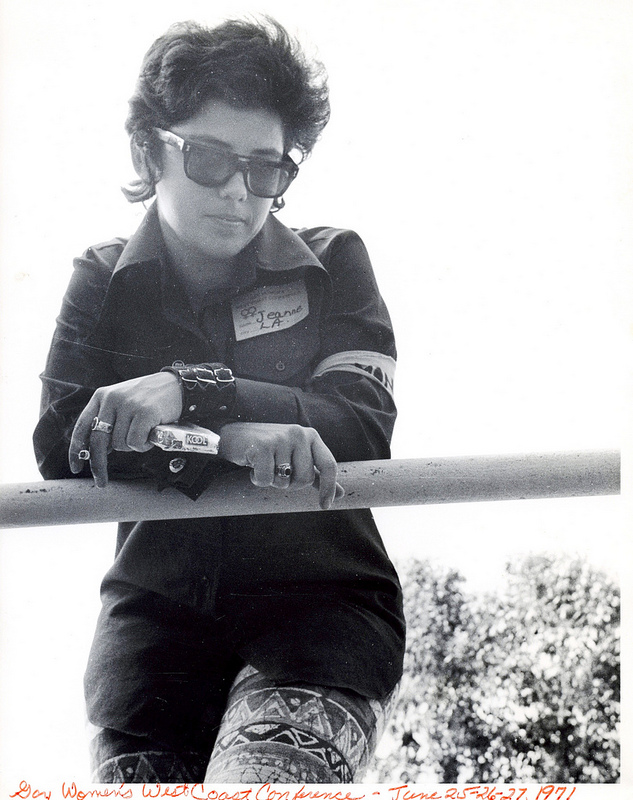

Jeanne Córdova

Riese Bernard: Listen, founding The Lesbian Tide and generally being a kickass butch lesbian writer and activist is enough but also, Jeanne Cordova left Autostraddle a gift in her estate, which Sally Ride unfortunately did not do, although I do love Sally Ride with all my heart. You can read more about my love for Jeanne Cordova in Thank You Jeanne Córdova, Love Autostraddle Dot Com and Jeanne Córdova Dies At 67: Goodbye to the Activist and Writer Who Lead The Way We’re Going.

Fill In Your 50s, 60s, and 70s Butch History With This Coloring Book

“[T]he legacy of leading and living as Butch was, is, and remains — quite remarkable,” writes Sasha T. Goldberg in the introduction to the Butch Lesbians of the 50s, 60s, and 70s Coloring Book — a book that is “not only a love letter to mid-century Butches, but a detailed map for those of us who have been looking (and looking), and for those us of us who simply cannot stop looking.”

For all that butches in 20s, 30s, and 40s faced certain challenges, in the 50s, 60s, and 70s they would face even more: the lavender scare, the US government’s Cold-War-era queer witch hunt; “cures” for homosexuality; butchphobia from lesbian movements and feminist movements; gender policing; racism; sexism; and more. This coloring book features the butch activists, artists, feminists, outlaws and others of that time, including Angela Calomiris, Gladys Bentley, Donna Butkett, Esther Eng, Adrienne Fuzee, Honey Lee Cottress, Chavela Vargas, Margo Rivera-Weiss, Olive Yang, Jane Rule, Esther Newton, Pat Bond, Frede Baulé, Peaches Stevens, Butchy McCausland, Barbara Smith, Jeanne Córdova and so many others.

Below: some printable coloring pages of butches for your very own. Share your art projects in the comments.

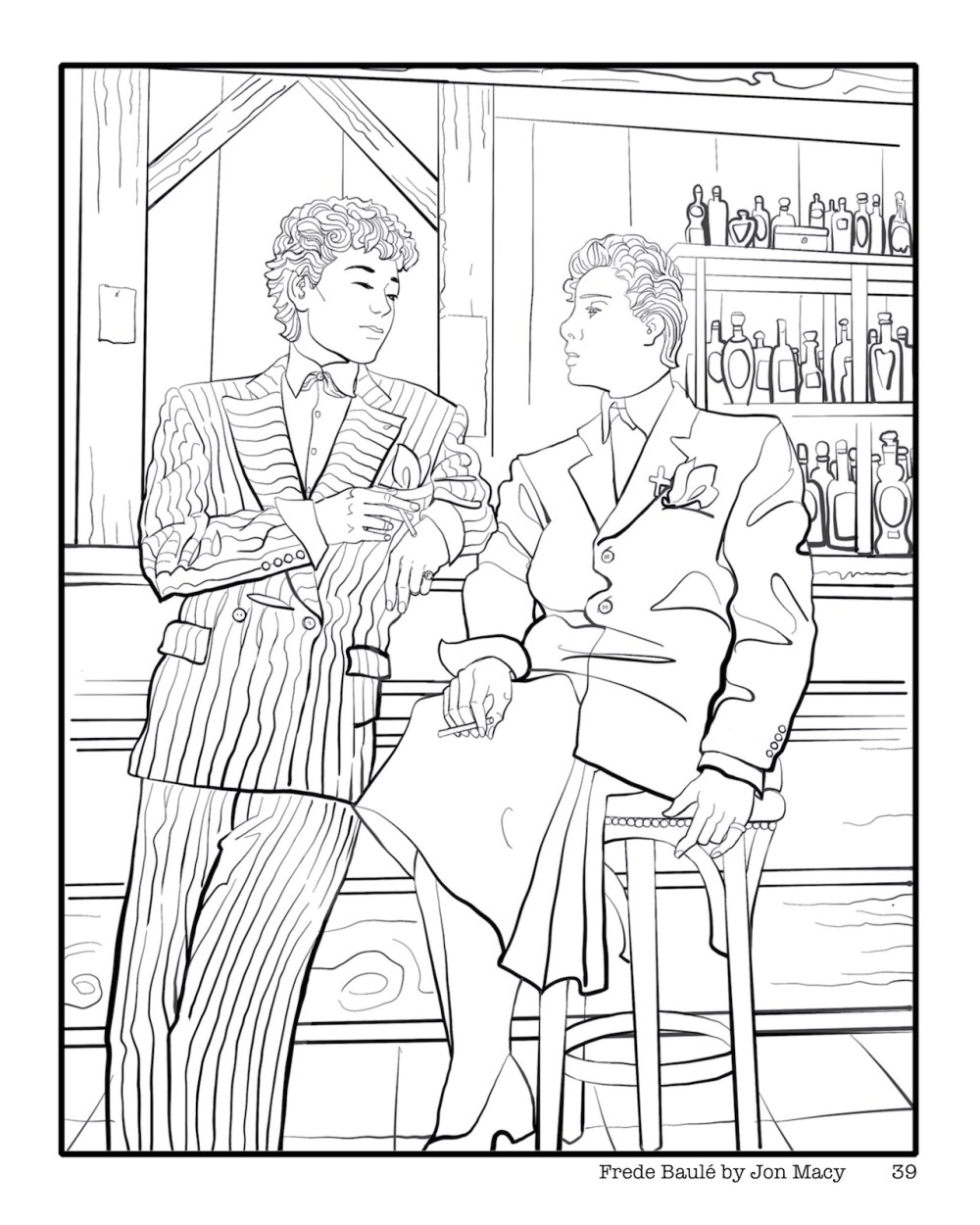

Frede Baulé, 1914–1976, France

Drawn by Jon Macy.

Frede Baulé was a French sex worker at Lulu de Montparnasse’s lesbian club Le Monocle. At 62, her obituary in France-Soir read in part: “She who, for the civil status, was only Frédérique Baulé, must be considered as one of the greatest seducers of her time. At her hunt table were the most beautiful women of Paris.”

Donna Burkett, 1946–unknown, US

Drawn by Ajuan Mance.

Donna Burkett came out at age seven, ran away to join the army at age 16, quit the army due to racism and joined the civil rights and gay movements. On October 1, 1971, she and her girlfriend Manonia Evans applied for a marriage license in Milwaukee, were rejected, and went to federal court over their right to marry.

Joe Carstairs, 1900–1993, Great Britain and the Bahamas

Drawn by Jon Macy.

Joe Carstairs, who owned custom boats and at least four small islands, was a speedboat racer with a string of famous femme exes. Marlene Dietrich’s daughter says of the first time Marlene saw Joe: “At the helm, a beautiful boy, bronzed and sleek — even from a distance, one sensed the power of his rippling muscles of his tight chest and haunches….The first thought on seeing him had been ‘pirate’—followed by ‘pillage’ and ‘plunder’ […] he turned from a sexy boy into a sexy, flat-chested woman.”

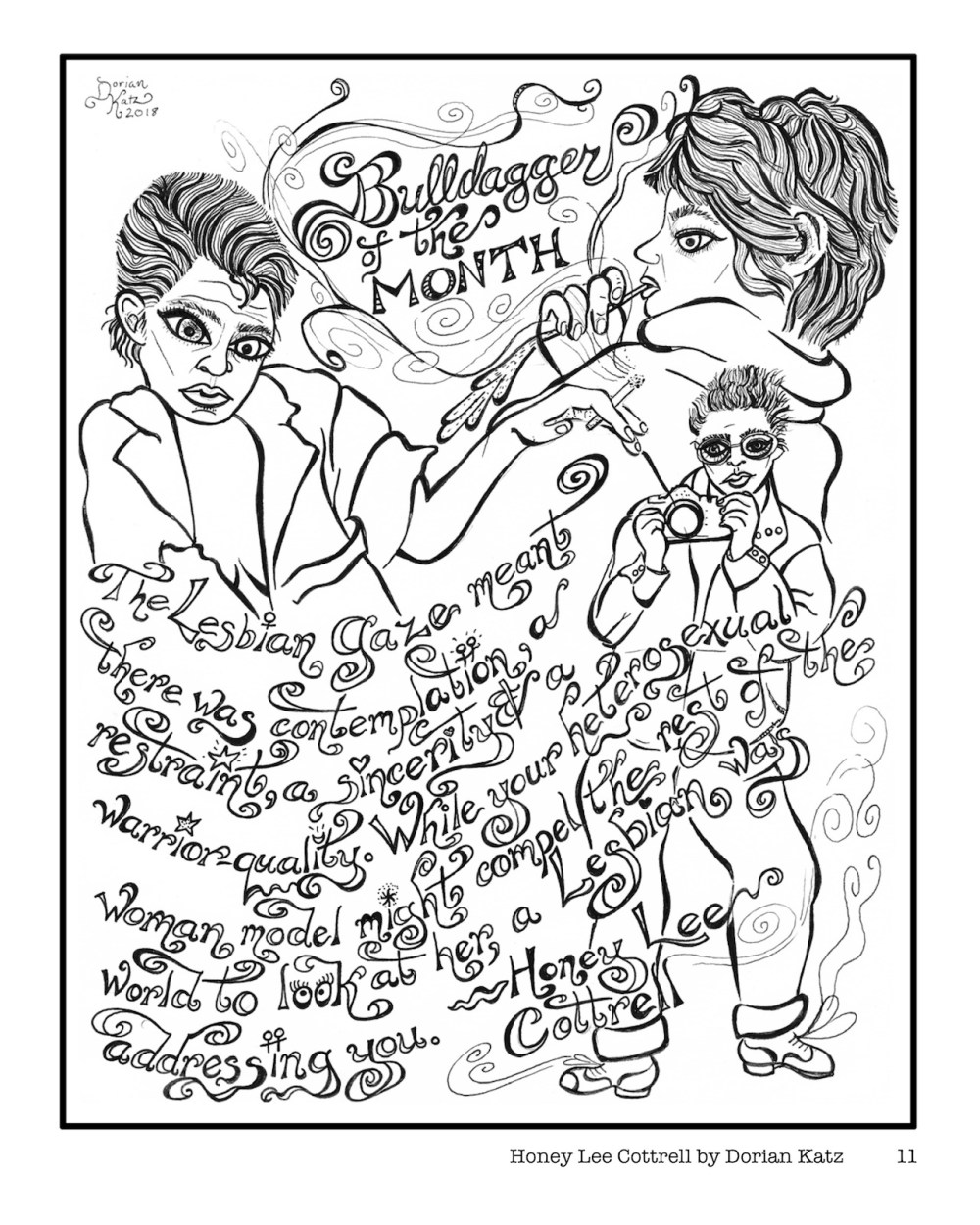

Honey Lee Cottrell, 1946–2016, US

Drawn by Dorian Katz.

Honey Lee Cottrell was a photographer and filmmaker known for her documentation of lesbian sexuality in the 1980s, her work in lesbian sexuality and education, and her work in On Our Backs, including staring as the first “Bulldagger of the Month” centerfold. She co-authored or appears in I Am My Lover, The Blatant Image, Coming to Power (read Autostraddle’s review), Sinister Widsom and Nothing But The Girl.

Stormé DeLarverie, 1920–2014, US

Drawn by Jennifer Camper.

Stormé DeLarverie toured as a baritone jazz singer and drag king in 1955, participated in Stonewall, and helped with anti-abuse community work.

Esther Eng, 1914–1970, US and Hong Kong

Drawn by Margo Rivera-Weiss.

Esther Eng was an out Chinese American filmmaker and New York City restaurant owner, the first woman to direct Chinese-language films in the United States, and the only woman director in the United States between 1943 and 1949. Film critic Law Kar writes: “If Eng had worked in the film industry today, she could have easily been seen as a champion of transnational filmmaking, feminist filmmaking, or antiwar filmmaking.” Her films did not survive intact.

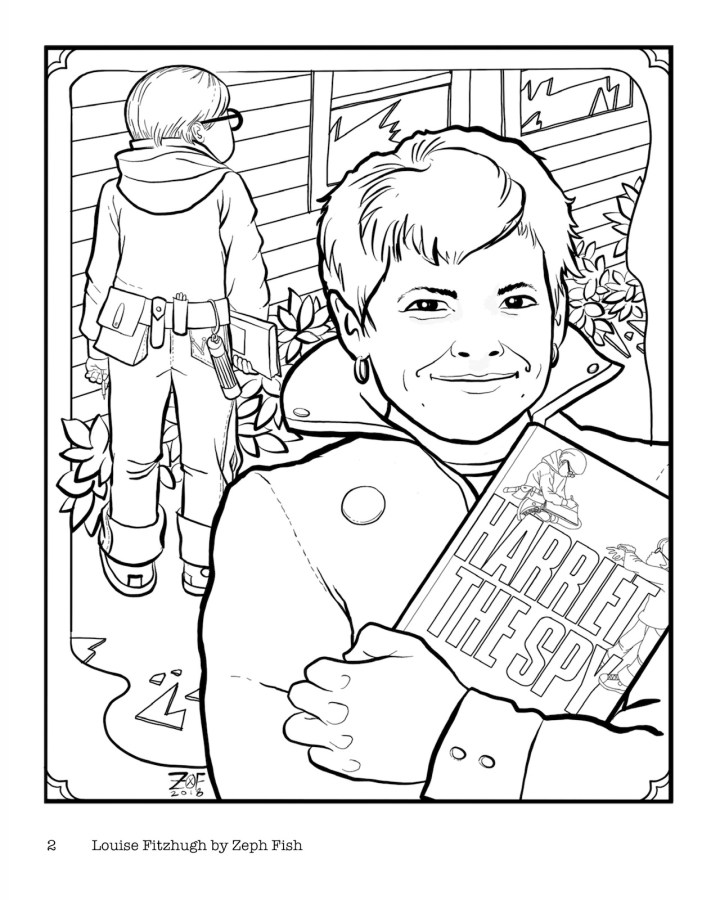

Louise Fitzhugh, 1928–1974, US

Drawn by Zeph Fish.

Louise Fitzhugh is best-known as the author of Harriet the Spy, which has been rumoured to be based on its author’s life; many of Harrison Withers’s cats are named after Louise’s friends, and one, Alixe Gordon, was named after her then-girlfriend. Fitzhugh also wrote a sequel to Harriet about menstruation, The Long Secret, and her never-published Amelia would have been the first lesbian YA romance in the United States.

Pat Parker, 1944–1989, US

Drawn by JessicaRenee BogacMoore.

Pat Parker was a radical feminist, came out as a lesbian in 1968, and became an activist in the Black Panther Party. She founded the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council in 1980. In 2016, her long out-of-print works were rereleased as an edited collection.

Thank You Jeanne Córdova, Love Autostraddle Dot Com

“Being an organizer and journalist in the lesbian, gay, feminist and women of color communities — and loving it — has been the focal point of my life. It has been a wild joyous ride,” lesbian publishing pioneer and activist Jeanne Córdova wrote in a “Letter About Dying, to My Lesbian Communities,” an email she distributed to her network in September 2015 while saddled with what she called “chemo-brain.”

Jeanne Córdova, a self-identified Chicana butch lesbian feminist, described her battle with cancer since a 2008 diagnosis and its 2013 comeback, and lately feeling like she was dying “in increments, one piece at a time.” In anticipation of her passing she wanted to tell her lesbian community that she loved us, and also to discuss her plans for her estate.

If you’re familiar with Córdova’s early work within the lesbian feminist community, it might surprise you, as it did me, that she even had an “estate.” Throughout Jeanne’s twenties, she’d struggled to make ends meet and often relied on food stamps while running groundbreaking Los Angeles publication The Lesbian Tide, reporting for LA Weekly and devoting every spare minute to lesbian feminist activism. She was The Tide‘s only full-time employee, finally making a salary of $7,500 a year (around $21k in today’s money) at the time of the magazine’s shuttering in 1980. The Tide, which aimed to do for lesbians what The Advocate did for gay men, remains one of lesbian publishing’s most highly revered and longest-running magazines, covering an unprecedented breadth of topics and filling its pages with ads for feminist and lesbian publications, bars, music and events.

Jeanne Córdova

In 1981, Córdova unexpectedly tapped into a profitable project with the launch of the Gay & Lesbian Community Yellow Pages. Coupled with some smart real estate investments, Córdova gradually established a sizable estate and made “an early personal vow” to give half of it back “to the movement.” The majority — $2 million dollars — would go to the Astraea Lesbian Foundation For Justice, and she encouraged her peers to “not think heterosexually [about wealth], like ‘I’ll give it to some random relative that I’ve never met. We need to think about giving to our gay or lesbian youth and institutions like Astraea or other lesbian organizations. They’re the ones who are nurturing our real daughters right now, around the world.”

In this spirit, smaller parcels of the estate were designated to be delivered to a number of like-minded non-profits, projects and publications. Autostraddle.com was one of them.

In July of 2015, Jeanne Córdova reached out to me directly, saying she was considering making a large donation and asking if we expected to be in business for the next five years. “I co-founded and ran the ‘Lesbian Tide‘ for many years and find your site very worthwhile in the same way,” she told me. I couldn’t believe Jeanne Córdova even knew we existed, let alone wanted to help us continue existing.

So I wanted to close out LGBTQ History Month with this story, because I think it’s an important one: because we are stronger when we reach out across generations to understand and support each other. Because this gift from Córdova is meaningful on multiple levels, uniting our past and our present and hopefully our future. Because in the spirit of her extensive work as a reporter, we have been steadily offering higher rates for reported features, hoping to elevate the discourse and tell important stories for and by our community. She made it possible for us to do that.

In her memoir When We Were Outlaws, Córdova details a life I know well — directing lesbian feminist media is hard work for so many specific reasons. The economic pressures, the working with friends/lovers/exes and their friends/lovers/exes, the political conflicts, the emotional processing. It’s complicated, exhausting, and irresistible work, but the rewards are immense. I’m so glad she saw a kindred spirit in Autostraddle.

We weren’t sure when the check would come or what it would be for, but it made landfall in July — and boy did we need it. It’s been a rough year, emotionally and financially, and although year-to-year revenue continues going up (because I’m good at my job), so do expenses. The cost of staying in the game still keeps us always on the verge. That check rescued us from “things are tight” to “things are okay” — and anybody who’s ever run a business or lived on a small budget knows how much time and stress is saved when every proposed expense isn’t an endless saga. That check has brought us much closer to our most pressing short-term goal, which’s to bring another woman of color onto our Senior Editors team.

When Jeanne passed in January 2016, I wrote an obituary that included an extensive history of The Lesbian Tide and its pioneering work, and you should read that, it’s important. Returning to that magazine over the past week while thinking about writing this post has been thrilling and familiar. It’s incredible how much we change and how little we change. The angry letters to the editor and the exhausted letters from the editors. The recaps of feminist conferences, the roundups of lesbian custody battles and hate crimes across the country, the grievances with mainstream feminism and gay men. But there’s so much joy, too, a keen sense of humor and enthusiastic determination. Love for the community radiates from every page, as does sarcastic acknowledgments of dire circumstances: “we realize once again what we realize every month with menstrual regularity — our litany of ‘not-enoughs’: not enough news coverage, not enough graphics, not enough in-depth analysis, not enough staff, not enough time, and of course, not enough money,” followed by a solicitation for help and support “in the most seductive spirit of lesbian love.” It feels like a secret clubhouse we’re all so lucky to be a part of, even when it’s hard.

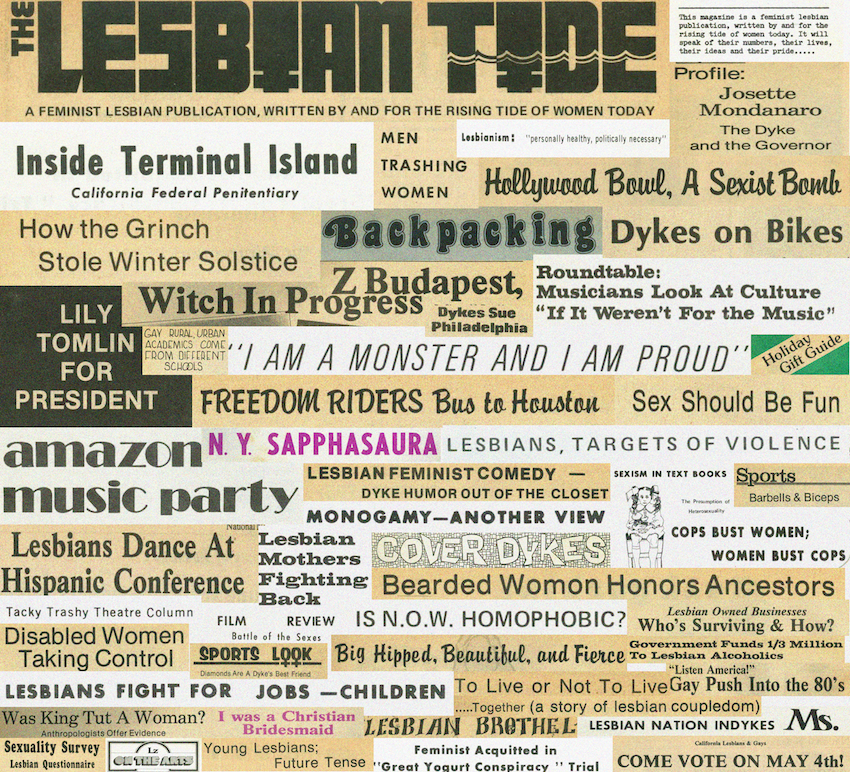

There’s a pitch-perfect blend of playfulness and righteous anger, nostalgic picture collages from Women’s Music Festivals, biting comics about lesbian relationships, profiles of musicians and witches, calls to action, expansive reader surveys. There’s a mish-mash of visual styles as diverse as the community itself, getting more and more polished as the years go on, invoking some nostalgia for the hand-lettered headlines of yore. It’s easy to see the parallels between them and us.

Headlines from The Lesbian Tide, 1971-1980

This post was intended to go up early today, but last night we got some bad news that derailed the evening and some of that bled into this morning and threatened the wilting afternoon. But like I said: it’s Lesbian Herstory Month and we’re doing this.

When We Were Outlaws opens in the aftermath of the 1973 National Lesbian Conference she’d co-coordinated, which she describes as “a moment of divination and a specific kind of hell,” riddled with in-fighting that “split our community into rabidly disparate political ideologies.” Conflicts arose over transgender inclusion, a “divisive rant” from Robin Morgan, Kate Milllet’s “public drunkenness” at her own keynote, and some complications involving the Socialist Worker’s Party. Córdova was traumatized by the experience, enduring “highly charged arguments of warring dyke tribes.” She’d put her heart into it but that hadn’t ended up mattering, not really. Following the conference, she “simply crashed into a full-blown nervous breakdown.” She ended up fleeing Los Angeles and the community she’d midwifed. She spent seven months upstate, laying low while lesbian feminist media descended on her and other easy, misguided targets. She remembers, “All I could do was mark the rising and the setting of the sun as I crouched in random corners of her living room, rocking myself to sleep.”

Whenever I convene with other publishers and movement-builders, regardless of age, we always come around to this — our beloved LGBTQ community’s enormous capacity for generosity and comfort, but also for ruthless accusations of bad faith that cut close to our earnest bleeding hearts. When I’m asked how I, as a woman in the media, handle the chronic harassment from men experienced by most women in the media, I’m hesitant to admit the truth: despite my passionate misandry and the fact that men are solely responsible for a solid bulk of everything bad in the world, the vast majority of social media bullying I experience is not coming from men.

Perhaps this is the way it must be, has always been, will always be. When we’re unclear on the appropriate moment for the personal to become political, when your demographic is chronically exhausted and underpaid, when the work is hard and complicated and, at least for me, when your empathy for all sides of a conflict can override your ability to decisively lead and take defiant risks. Today, reeling from a situation with an ad network pulling out some truly ridiculous stops to avoid paying us a much-needed pile of money they owe us, I was unseated from a fragile precipice by assholes on twitter and combative comments. My skin should be thicker by now, but I think it gets thinner every year, wearing down, exposing vulnerable bones. I spiraled. I’ve spiraled before. Laneia and my ex-girlfriends can tell you all about it. When various forces align to make everything feel impossible and insurmountable and I declare I can’t do this anymore and go hide in my bed.

So I shut off my computer and phone and walked through my yard to the forest behind it, going as far as I could, traipsing through the defiantly picturesque fall foliage, getting brambles stuck on my leggings and mud on my busted boots. I walked in circles like a crazy person. I sat on a log and cried. I looked at the sky even though doing so made me feel like I was in an Abilify commercial, and I wondered how Jeanne Córdova bounced back, and I remembered how reading The Lesbian Tide sometimes feels like looking in the mirror. I wondered how she stayed strong through everything, with limited funding in a hostile political climate, butting against the ridiculous assertion that everybody in a specific demographic group should be fighting for the same thing at the same time, that different focuses cannot co-exist but must compete.

The bulk of When We Were Outlaws traces a conflict between the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center (and the mostly gay men who run it) and lesbian feminists formerly employed by it. Córdova was thrust into the middle of the battle, struggling to reconcile her own opinions and loyalties as well as the relentless criticism and accusations of betrayal from allies on both sides and the pressing urge to break off entirely from gay men in order to achieve lasting change for women. She eventually concludes, “Waging a labor battle, inside a gender war, surrounded by a movement for civil rights, portended an untenable conflict with no exit strategy tied to anything I could have called victory.” That sentence likely seems senseless out of context but it’s not, really, it’s just a pretty dead-on description of so many of the conflicts that threaten not just to tear us apart, but totally wear us out and wipe us out.

Today, in the woods, I did my best to draw strength not from my usual sources, but instead from lesbian history, from our imperfect legacy. From Córdova’s assertion that “sometimes in the losing is the winning; and in the struggle, is the living.” From how she picked up after that conference and went on to organize more conferences, and kept writing, and kept advocating. This gift was about the money, sure, but it was also about the vote of confidence. That maybe this was a calling and I have answered it. I promised her we had five more years, at least. I’ve promised you as much, in so many words too. Because it’s worth it, even when it’s hard.

“You gave me a life’s cause,” Córdova wrote in her Letter, a sentiment I relate to intensely. “It is wonderful to have had a life’s cause: freedom and dignity for lesbians. I believe that’s what lesbian feminism is really about, sharing. We built a movement by telling each other our lives and thoughts about the way life should be. We cut against the grain and re-thought almost everything.”

And then, she remembers, she writes, she thinks: “With just enough left undone for our daughters to re-invent themselves.”

Jeanne Córdova Dies At 67: Goodbye to the Activist and Writer Who Lead The Way We’re Going

You gave me a life’s cause. It is wonderful to have had a life’s cause: freedom and dignity for lesbians. I believe that’s what lesbian feminism is really about, sharing. We built a movement by telling each other our lives and thoughts about the way life should be. We cut against the grain and re-thought almost everything. With just enough left undone for our daughters to re-invent themselves.

– Jeanne Córdova, A Letter About Dying, To My Lesbian Communities, September 2015

Jeanne Córdova, the legendary lesbian activist, publisher, and writer, passed away early Sunday morning at the age of 67 after an extended battle with cancer. She was in her Los Angeles home with her partner of 25 years, radio talk show host Lynn Ballen, as well as her friends Jenny Pizer, Doreena Wong and Dina Evans.

Jeanne Córdova

Córdova’s contributions to the lesbian community cannot be overstated, and they will continue on, as she chose to bequeath $2 million to The Astaea Lesbian Foundation for Justice to create The Jeanne R. Córdova Fund. The Fund will be devoted to the support of organizations focusing on movement building, human rights and journalism with a specific focus on Latina lesbians from South/Latin America and South African women; lesbians, feminists, lesbian feminists, butch and masculine gender nonconforming communities.

“I feel strongly that we should not think heterosexually [about wealth], like ‘I’ll give it to some random relative that I’ve never met,” Córdova said of her decision to make this donation. “We need to think about giving to our gay or lesbian youth and institutions like Astraea or other lesbian organizations. They’re the ones who are nurturing our real daughters right now, around the world.”

left to right, Ivy Bottini, Jean O’Leary, Jeanne Cordova, Robin Tyler. via Robin Tyler’s facebook page via Frontiers Media

In these infinitely more accepting times, it’s more important than ever to remember, pay tribute to, and celebrate the lives of foremothers like Córdova. Especially right here, in this space, right now, because we would not exist were it not for all the publications for lesbian, queer and bisexual women that came before us — the community they built, the stories they shared, the political issues they hashed out and the divisions they investigated. In an e-mail last year, Córdova told me she felt Autostraddle was “worthwhile in the same way” as her pioneering publication, The Lesbian Tide. It was an incredible compliment.

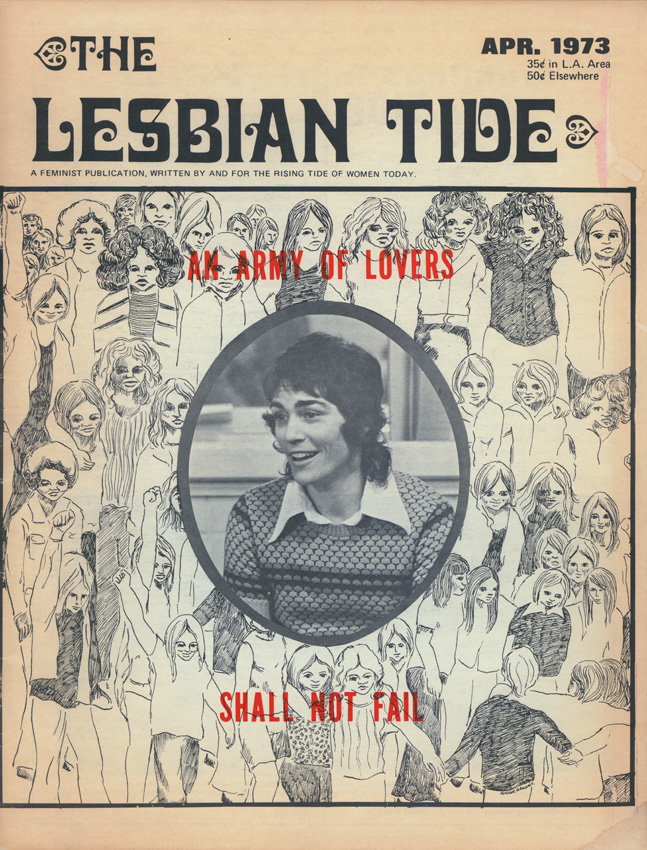

The Lesbian Tide began in 1971 as a newsletter for the Los Angeles chapter of the lesbian rights organization Daughters of Bilitis. In her 2015 “Letter About Dying, to My Lesbian Communities” quoted above, she recalled that “from the age of 18 to 21, I painfully looked everywhere for Lesbian Nation. On October 3, 1970, a day I celebrate as my political birthday, I found Her in a small DOB (Daughters of Bilitis) meeting. That’s when my life’s work became clear.”

However, The Tide‘s young radicals often clashed with elder DOB activists and in 1972, it split from the DOB with Jeanne Córdova as editor. “Bigger things were happening than DOB,” she told Rodger Streitmatter, as quoted in his book Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. “I was 23 years old and wanted to cover them my way.”

A survey in the late ’70s of Advocate readers found a whopping 97% of its audience to be men, and Córdova wanted The Lesbian Tide to provide for lesbians what The Advocate did for its community. The two most prominent lesbian publications of the ’70s — a veritable golden age for lesbian publications — were The Furies and The Lesbian Tide. Starting with about 100 readers, by 1977 the magazine had a circulation of 3,000 and was sold in eighty bookstores. It is estimated that in 1975, around 50 lesbian publications existed and collectively boasted around 50,000 readers, which unfortunately didn’t exceed that of The Advocate‘s circulation alone. It was much harder to reach out to and build community amongst lesbian women, who often lacked the economic mobility white gay men had greater access to because of The Patriarchy.

The Tide was specifically a lesbian feminist publication, defining lesbian feminists as “women who devoted themselves entirely to women for social, emotional, physical and economic support.” It abandoned fiction, a mainstay of other lesbian publications, in favor of news and reporting on cultural issues. “I didn’t want my lesbianism to be just a matter of sexuality,” Córdova said. “I felt it was more political than that really.”

via facebook

The Tide solicited stories from readers around the country and prioritized lesbian voices, wholeheartedly refusing to use straight people or gay men as sources of information or funding. At a time when the position of women in American culture was even worse than it is today, this type of insular movement building was crucial and empowering. Despite the generally anti-trans sentiments of lesbian feminists of the era, The Tide had a lesbian transgender photographer, and Córdova recently told writer Anna Mollow “anyone who called herself a woman was welcome to serve on our staff.” More recently, Córdova also publicly supported the inclusion of trans women at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.

Although what they were able to pay their writers wasn’t much — often only five dollars — it was important to Córdova that nobody was working for free. She was the only full-time employee of the magazine, making a salary of $7,500 a year (around $21k in today’s money) by the time the magazine folded in 1980. They struggled to survive off advertising solely from lesbian businesses and often directly asked their readers for money (in all caps, obvs).

The Lesbian Tide covered a myriad of issues and topics: politics, education, butch/femme roles, motorcycle racing, lesbian music, the Goddess movement, non-monogamy, dyke separatism and more. (You can read a sample issue of The Lesbian Tide here.) Córdova was also the first lesbian journalist to talk about lesbian BDSM, however, recalling in Unspeakable, “Feminists were obsessed with politically correct sex. We had more letters on our S & M coverage than any other subject in our nine years of publishing.”

The Tide‘s community carried over into real life, too: on a smaller, local level, they formed their own softball and football teams and did things like hosting fund-raising events for lesbian prisoners. In 1973, Córdova and the staff of The Lesbian Tide were key organizers of the National Lesbian Conference in Los Angeles, which was, at its time, the biggest gathering of lesbians ever. Previously, Córdova had organized the West Coast Lesbian Conference in 1971 and would go on to serve as a delegate to the first National Women’s Conference in 1977. In 2010, she chaired the Butch Voices Conference in Los Angeles.

The Lesbian Tide is only a one part of her prolific life’s work as an editor, writer and journalist.

As an investigative reporter and Human Rights editor for the Los Angeles Free Press, she interviewed activist Angela Davis and Emily Harris of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, she produced The Community Yellow Pages, an LGBT business directory. In 1987-1992 she published the The New Age Telephone Book and, from 1992-1994, produced Square Peg magazine, which (according to Unspeakable) focused on “the lesbian and gay good life.” It included club listings and an advice column with a lesbian and a gay psychotherapist, as well as featuring lesbian comics like Suzanne Westenhoefer and Lea DeLaria. Square Peg is also notable for its valiant effort to get Jodie Foster to come out after winning her Oscar for Silence of the Lambs (no luck). In 1997, she published The Spirit of Todos Santos, an arts & culture magazine serving the town of Todos Santos in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

She published three books, most notably When We Were Outlaws: A Memoir of Love & Revolution in 2011, which you should probably buy and read today. Her work has appeared in publications including The Guardian, The Nation, The Washington Blade, The Bay Area Reporter, The Advocate, The Lesbian News and The Los Angeles Village View. Essays have appeared in anthologies including The Right Side of History: 100 Years of LGBTQ Activism, Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme, Untangling the Knot: Queer Voices on Marriage, Relationships and Identity, Persistent Desire: A Femme Butch Reader and Lesbian Nuns: Breaking the Silence.

Córdova was also very involved as an activist in the ’70s and ’80s, helping to found the Gay and Lesbian Caucus of the Democratic Party, serving as the media director to defeat the Briggs Initiative, and serving as president of the Stonewall Democratic Club.

After selling The Community Yellow Pages in 1999, she moved with her partner Lynn Ballen, the daughter of South African freedom fighter Frederick John Harris, to Mexico, where they co-founded The Palapa Society of Todos Santos, AC, a nonprofit focused on economic justice. They returned to California in 2007, where they co-founded LEX – The Lesbian Exploratorium and created the Lesbian Legacy Wall at ONE Archives (Córdova had been elected Board President of ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in 1995). Ballen and Cordova continued hosting and planning history-themed lesbian feminist cultural events together in California throughout their lives together.

LOS ANGELES, CA – MAY 26: Susan Forrest (R) takes a snapshot of Jeanne Cordova (L) and Lynn Ballen (2L), as Forrest’s partner Talia Betther looks on, as they lead a chant for demonstrators outside the East Los Angeles Marriage License Office May 26, 2009 in Los Angeles, California.(Photo by Robert Hanashiro-Pool/Getty Images)

She was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2008, and by 2013, it had metastasized to her lungs and to her brain. The chemo that fought the cancer also produced increasingly unbearable side effects. “The choice appears to be living with chemo forever off and on, or dying,” she wrote in her letter. “I will make that choice soon enough.”

Being an organizer and journalist in the lesbian, gay, feminist, and women of color communities—and loving it–has been the focal point, of my life. It has been a wild joyous ride. I feel more than adequately thanked by the many awards I have received from all the queer communities, and through all the descriptions and quotes in history books that have documented my role as an organizer, publisher, speaker, and author. Thanks to all of you who have given me a place in our history.