New DIY Documentary Honors AIDS Media Activism, Love, Loss, and Queer Community

Last March, I met filmmaker and scholar Alexandra Juhasz outside the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. She was in the middle of a Film/Video Studio Residency at the Wex, as it’s known as here in Columbus, working closely with an editor on post-production of her experimental documentary Please Hold.

Please Hold, which premiered earlier this March, explores the intersections of activism, memory, and media via a profoundly personal yet communal lens. It is anchored by videos of two of Juhasz’s closest collaborators and late friends in the last stages of their lives. Shot on a mix of consumer-grade recording devices — iPhone, Zoom, VHS camcorder, and Super-8 film — the documentary is an homage to grassroots AIDS mediamaking across decades and its ability to capture intimate, honest communication about hope and loss.

I was profoundly moved that Juhasz invited me into the studio with her to watch a cut of the film. A prolific writer and filmmaker, Juhasz is a Distinguished Professor of Film at Brooklyn College, CUNY. She produced and acted in the renowned feature documentaries The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1996, and its remaster, 2016) and The Owls (Dunye, 2010). For decades, Juhasz has written, directed, and produced her own documentary features and shorts, which have screened widely in feminist, queer, and experimental documentary festivals. She has written extensively on HIV/AIDS, including the recent publications We Are Having this Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production with Ted Kerr and AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, edited with Jih-Fei Cheng and Nishant Shahani.

I first encountered Juhasz’s writing in grad school while studying LGBTQ media, history, and activism. Her book AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video, deeply shaped the way I theorized about LGBTQ local television in my own work. While preparing to begin my dissertation, I emailed Juhasz for advice about how best to write about these topics. I was looking for possibility-models, other scholar-activists who do research in the service of social justice and queer community. Since then, Juhasz has supported my work in many ways, including connecting me with media makers I interviewed for my dissertation.

As we watched the documentary together in the studio at the Wex, I realized that Please Hold honors one of these same media makers: Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, a Black disabled queer feminist media activist who died in 2022. I spoke with Szczepanski years earlier about her work creating AIDS education media for the Audio-Visual Department of the Gay Men Health Crisis in the 1990s, after Juhasz connected us. I hadn’t realized the film would document Szczepanski’s last days. Watching the film next to Juhasz and her editor, I realized we were both holding Szczepanski’s memory, and our connections to her, in different ways. To know Alex Juhasz is to be held in community, a privilege and an honor that connects you to her own deeply felt responsibility to making the world a more livable place for marginalized people.

It was a pleasure to speak with Juhasz more about the film’s production, how it explores grief and loss, her approach to activist media making and distribution, and the importance of LGBTQ communities of care. Our conversation below has been lightly edited and condensed. Please Hold is available to watch for free on the film’s website and you can book a screening of it here.

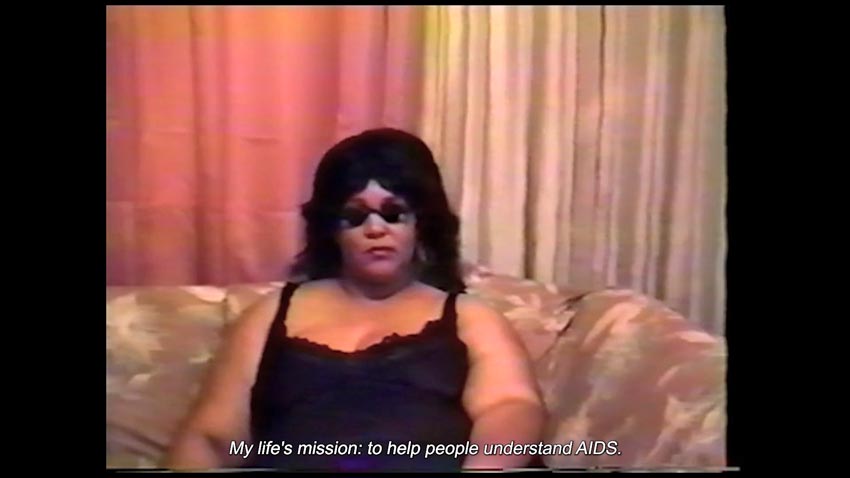

Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski in “WAVE: Self-Portraits” (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise, 1990, VHS).

Lauren: Could tell me about the origins of this project and what inspired you to create it?

Alex: Thank you for asking. This video began because, during the COVID pandemic, my very good friend and a collaborator of mine on AIDS activist media, Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, asked me to shoot video tape of her in the process of dying. She more or less chose the terms of her own death because she stopped receiving dialysis.

I came to videotape her twice in rehab centers in New York. And after that, I made a video that she had wanted from those materials called I Want to Leave a Legacy. When I was making that video, I realized that at a previous moment in my life, another very close person to me had asked me to make a video with him in the late stages of his life. That was my best friend, James Robert Lamb.

I wanted to think about the responsibility of holding those two documents, but also how they produced this very clear arc about some histories of HIV/AIDS in the United States, which is to say, my friend Jim is a sort of poster boy from the first years of the pandemic: gay white man, very pretty, an actor. He died when he was 29 years old. There was no medication, and he had a very painful death. The videotape that I shot of him all those years ago when we were young was very strange actually, because I think his mental state was affected by his impending death.

And then fast forward 30 or so years: Juanita is a Black disabled woman who’s a lifelong AIDS activist, who doesn’t die of HIV, but dies in community that’s been produced around collaborative art making and is really committed to disability justice and dies within the time of COVID and because of health inequalities that were escalated because of COVID.

My responsibility, what I can learn from those tapes, what they tell me about HIV/AIDS, and also what they tell me about living through dying, and making community even as people are dying — that’s what started it.

Lauren: Can you tell me how the film itself explores grief, memory, loss, and those relationships?

Alex: The video wants to think about technologies of memory, various receptacles that hold something of a person that you loved after they die. It could be a trace of them, but it could be work you’ve done together. This is very important to this project. They are people that I engage in art making and activism with. I know that various technologies shape memory and shape grief differently.

So, it really wants to think about how VHS, which is what I shot Jim on, has a different almost metabolism than an iPhone video, which is what I shot Juanita on. While they are both media that are holding traces and memories and conversations and activity with these people, I think that they’re held differently.

I was thinking about those two media to think about material things, like in the case of the film, a sweater and a scarf that emerge. Then I extend that to my own body and I think about the fact that I’ve aged. Grief changes as the body holds it. I think about neighborhoods, so places that one returns to and how they trigger memories, but they change, so they hold memory differently as well.

I think the other thing I would want to say, just from having screened it quite a bit in small groups at this point: It doesn’t work with grief quite like we expect movies to. It’s not triumphant, it’s not organized around catharsis necessarily. It doesn’t have music that tells you when to feel bad or good. It doesn’t have the typical beats that cinema is organized around, but I think it has the typical beats that life is organized around, which is this kind of pulsing.

Sometimes grief feels like celebration. Sometimes grief feels like connection. And sometimes it’s very hard to process. Jim died when I was a girl, and I’ve lived with his death longer than he was alive. My grief for him is very different than my grief for Juanita, who died only a few years ago.

We’re in a time organized by grief and mourning. Even if it’s not for the loss of people, it’s for the loss of our democracy and the loss of structures that made sense to us. It lets you come in where you are and acknowledges that’s changing. It might even change over those 70 minutes of the video.

Lauren: You mentioned that iPhones metabolize grief differently than VHS. I’m wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about the mixed media approach to this film, how you decided to combine all these different types of film making, and why that was important for you.

Alex: What it feels like to make media with different technologies, that’s always for me part of thinking of what medium is. A camcorder is actually heavy, and there’s a kind of commitment that to work with heavy equipment demands. iPhones are very light and they are very easy to use and they’re extremely easy to shoot things with and extremely easy to take that footage and put it somewhere else and distribute it and share it and see it.

And therefore, one of the ways that they’re different is that we’re constantly shooting video that is completely expendable. It’s hard to know the difference between the important things you shoot and the not important things you shoot. It’s interchangeable. So that lightness of the iPhone material, the lightness of social media, and I mean that literally but also metaphorically, is part of what I’m thinking about. When Juanita asked me to come shoot her on her deathbed, she had wanted me to shoot her on a camcorder and she didn’t have the power cord, so I took out my iPhone.

But it’s not just the technology. Watching someone die is a cosmic shift. If someone asks you to be part of that, that’s an incredible responsibility and it’s a heavy responsibility. It’s a beautiful responsibility. So, it’s not just that I had the iPhone. I had made this agreement. She had asked me and I didn’t even know why she had asked me initially. It’s in the footage, she tells me, but she’d asked me to do this. I wanted to mark the heaviness of the weight of it, the beauty of it.

This is where the project is about what it means to be in community and collaboration. It’s a very different kind of relationship to media making. It’s activist media making.

In Please Hold, I use video compositing a lot. I think it’s the visual and media language that defines this moment in history. It’s very desktop-looking on purpose and very collage-y. The collage holds VHS and iPhone videos next to each other, or digital video and iPhone video and then text on top of that. I’m interested in that collage aesthetic that flattens the discrete technologies. Then I work very hard to keep reminding you that they are discrete technologies.

In every shot of video, I tell you what kind of camera it was shot on and when it was shot because, again, I think that the computer screen that you and I are looking at right now equalizes, flattens things. I’m both interested in seeing that as an aesthetic and thinking about what it does.

The film is about grief, it’s about memory, but it’s also about communication. It’s also about me talking to people who have died and me talking about people who are very much alive, who I’m in activist community with. I’m trying to think visually about the sort of flatness of the screen and the depth of the interaction. That’s what that compositing does to me. But that’s also having the Zoom interviews where you see two people, like we’re doing right now, as opposed to a more traditional talking head. You’re constantly aware of the depth, the third dimension of the screen, because the listener produces that.

Lauren: I wanted to ask you about the Zoom interviews. How did you decide to incorporate these conversations with folks that you’re in activist community with?

Alex: Video Remains is the video that I made with my footage from my friend Jim’s and my one hour on the beach together in the last year of his life. It took me a long time to make that video and it’s very important to me. I think it has a place within the history of AIDS media that is a critical place.

This video [Please Hold] is referring to it in many ways and thinking about technological shifts. In Video Remains, I talked to my fellow AIDS activists, they were all women and lesbians, on the phone. That’s cut into the long take footage that Jim had asked that I shoot of him on the beach when he was telling the story of his life.

Fast forward to now, with these new technologies, I’m like, we wouldn’t talk on the phone, we would talk on Zoom. It parallels that method of sharing space and knowledge with collaborators and my activist community. The video that I made now is thinking about how COVID, and our experiences during lockdown in particular, rejiggered our expectations and relationships to communications technology.

It’s a recognition that that’s a new form of media making. I’m an activist media maker. I make things for nothing. I shoot them with whatever is at hand. I distribute them that way. And Zoom is an amazing, inexpensive form of technology to interview people. The interviews look and sound pretty good.

I am also trying to think about these different formats of connection, what it is to live together in a place, what it is to use a phone or Zoom, what it is to be in a place or be with a person who has been, that was recorded and you revisit.

The film really believes that we can continue to collaborate with the people we love after they die, or that I can, because I’m still asking the questions and working on projects and trying to make the changes that were very important to both me and Jim. I’m still committed. I need their voices. I need who they were to me and what they know and what we could make together. I can still use that, even when they’re no longer here, because we made these videos together. I’m so lucky.

Clockwise: James Robert Lamb, Pato Hebert, Alexandra Juhasz, Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski (built from “Video Remains,” Alexandra Juhasz, 2005, Zoom interviews, 2023, and “I Want to Leave a Legacy,” Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, 2022, iPhone).

Lauren: How else has this work impacted your life?

Alex: Right now I’m starting DIY and activist distribution, which I’m doing by myself. I’m trying to get it out in the world, but trying to get out in the world under the terms that seem right for me.

In the book that I wrote with Ted Kerr, [we write about] the idea of “trigger films” or “trigger videos,” [videos] from the early part of the AIDS crisis that you would show, stop the video in the middle of a scene, and then people would talk about it. We use the word “trigger” now differently. We talk about this in the book, but both uses of “trigger” are about setting terms for healthy conversation.

I think that Please Hold is also a trigger film. I think that what it’s best for is to spark conversation. And I think that, like so much on the internet, it shouldn’t be watched alone by yourself, with two other things on your screen. That’s probably true of a lot of art films. But I’m saying, it’s not just any art film. It’s a film that holds the traces of two people who died, who ask to be seen. It takes a lot from us as contemporary media viewers to change the way we’ve been taught to watch to be more human and to be more caring and to be more present.

I’ve tried to put a tiny scrim between getting the film for free, which I’m letting you do, and watching it with more care. You have to fill out a little form that says, “I’m going to watch it by myself. I’m going to watch it with some people. I’m going to set up a screening.” Then I send you the link. I don’t know if that’s going to work. But I’ve never really cared how many people see things that I make. I care about the context in which things are seen. That’s true of activist media more generally.

I want that context to be respectful and contemplative and interpersonal and give people space to talk afterwards, which so little viewing does now, especially when things are digital. The main thing I’m doing is trying to move it in the world and have conversations where I can be present with other people with what it brings up.

Lauren: That’s beautiful. That’s such an interesting way to experiment with distribution. I love that. As you’re talking about care, I was even thinking about your film We Care that I’ve showed in class a number of times, that is also about care and dying, so I can see those through lines in your work.

Alex: I think that the norms of dominant cinema push to the edge a lot of the things that actually can and do happen when we consume media together. One of those is the idea of care. That’s something you could build around screenings.

I think people do it, but you need to think about, in what conditions do you do that? Because the consumption of media now that we’re all on our laptops, it’s just violent and hurtful. It doesn’t matter if you’re consuming something you like. It doesn’t make you feel good. It’s the opposite of care, even if you’re watching something beautiful. The extratextual conditions of making and screening activist media are as important as the piece of media itself. And that’s what I’m doing by building out my own distribution.

The reason I made this was to talk to people about AIDS, and to talk to people about HIV, and to talk to people about memory, and to talk to people about dying, and to talk to people about community, and to talk to people about all the ways we love each other and all the ways we help each other, and how beautiful it is to be in community. I want to have that conversation every time it’s screened. I hope other people will talk to each other about those things. That’s why we make art, certainly activist art.

What we want from activist media is that you’re transformed, that you feel a transformation and you feel that you can interact, not just consume.

Lauren: That brings me to another question I wanted to ask. Can you tell me about the title Please Hold?

Alex: The first shot of the film — well it’s not the first shot anymore, it’s deeper into the film now — is me riding up an escalator at the Delansancy/Essex Street stop on the Lower East Side, the F train. It’s a long take, and I go up the staircase. I think it’s beautiful. It’s so dirty, and makes all this noise. It’s so industrial and of this other era and it evokes that neighborhood in New York City.

As you get to the top, you see this boy wearing this powder blue sweatshirt, and he’s on his phone, and he’s almost dancing. It’s like choreography. But if you look above him, there’s a LED sign and it’s saying, “Please hold the handrail.”

I was deep into editing the film and I’m like, “Oh my god, that sign says please hold!” If you listen to the film, I talk about holding all the time. The word “hold” is used in it over and over and over again. And I’ve already talked about it like that with you. I’m holding these memories, I’m holding these tapes. A lot of the people in the film help me think about holding things together.

My friend Ted [Kerr] talks about holding a sweatshirt of Jim’s that I had given him. That’s a way for Jim to stay with us, we hold it together. And then holding the Parkside, which is a gay bar, queer bar, and you’re holding that space. Jih-Fei [one of the interviewees in the film] talks about holding spaces when nobody will let you, which is very much about what we’re in right now. What it means to hold the space of trans identity or gender non-conforming identity or a bathroom that’s become dangerous territory, and they say you can’t use it, and you hold it. That is something that political people do.

The Parkside also holds ghosts, it holds porn magazines. So holding just constantly emerged in the process. But then the title was given to me by the Lower East Side. And of course, “please hold” is also what someone says on the phone in a not nice way, so it has that register as well. It makes you wait when you’re not ready to wait.

The film is also about walking as a technology of memory, how the world presents information to you when you’re ready to receive it. Walking can wake you up to take in input that you wouldn’t see. So the fact that the title is there because I’m walking in the neighborhood is very much an idea of the film that the world can help you too, if your body is open.

I’ve had the great luck to stay alive this whole time and my body is so different. There’s a lot of seeing me young and seeing me now in the split screens. There’s a lot seeing Juanita young and seeing Juanita now in split screens. There’s not that of Jim because I only have the images from that one period of his life and he didn’t get to live to be older.

My body at this age, I just turned 60, takes in the world differently than my body did when I was 29. And in a lot of the footage that you see, I’m 29. I actually understand the world differently through this technology. I think in a sexist world in particular, I say this as a cisgender woman, I think I understand the world much better in this body than I did when I was 29, and that’s why there’s so much ageism, especially against women, because people don’t want women to be smart in that way. They want to tell us these bodies are not useful tools and not intelligent receptacles. Quite the opposite, as we age, our bodies become smarter if we’re lucky, or wiser, or deeper, or more sophisticated. I do not need to be the 29 old girl that I see there. I’m very glad that I’m not.

Lauren: Thanks for sharing that. Is there anything else that you want to share, or that you want Autostraddle readers to know?

Alex: One of the things that I love about this movie is how queer it is. It is my definition of queer, everyone can have their own. What I love about it is that the characters that you meet are every kind of different. They’re every kind of deviant. They’re every kind of edge. And sure, you can say they’re lesbian, trans, gay, Jewish, Black, Asian, young, old.

But the movie is not committed to a particular slice of the queer world. It’s expansive about how queer love and queer community, queer analysis, queer ways of living and family and being political and caring and making relationships of care. That has been everything to me. And that’s true in my nuclear family, lesbian family, that’s very extended into other parental roles. It’s true in my queer romance with Jim. We lived together for many years.

It’s true in my very queer friendship with Juanita that crossed race and class and brought us together in an overt analysis that came from the celebration of gay and lesbian life and trans life. So I want the readers of Autostraddle to behold a feminist queerness that is my community and is me. I love being in this community. I love being seen by this community.

I love speaking to this community. I love the way the film stretches that inclusion and also its limits. That’s the queer lifeworld that I draw from in that video.

Lauren: Since it has been a couple months since Trump’s inauguration, I’m wondering how you feel about the film coming out right now and what you feel the film has to say about this contemporary moment.

Alex: I am as confused and hurt and angry and afraid and uncertain as anybody. I don’t have any answers right now at all. Many of the things that I thought were answers don’t seem to be. That’s super scary.

But what I just said to you about queer community and queer love that is connected to activism — not just who you have sex with or who you want to go to a party with, although that’s part of it, but connected to working together to make the world better for the most disenfranchised, the people who are the most weak and the most threatened at any particular moment. And sometimes, like right now, that is trans people, right now that is people in our world with HIV and AIDS who are truly about to be decimated by the end of PEPFAR and threats to Americans’ access to free medication.

Queer love and queer community that’s organized around wanting to help each other and help the most disenfranchised — that is always a goodness. The minutes you can spend in it or the hours you can spend in it are worldbuilding. They’re being in the world that we want and we deserve and we can make, and even if we can’t right now respond to the huge threats, and even as they will be endangering people we love, or killing people. Killing people in Africa via [the end of] PEPFAR, killing people in Gaza, killing people in the Ukraine, killing people in the Congo, I could go on.

We as humans can make little reprieves, little pockets, little sparks of beauty and dignity and decency. And queer people have always done that. We’ve had to. And so watching the film together, talking together, that’s just an example of knowing that we can make moments of power. It might not be big. We talked about how how many people watch something is not a register that matters to me. Smallness is often what you need to have deep impact. We can be in community and learn with each other. And so we will do that. We can do that. We are doing that. We have done that. And it might not change the badness, but it is itself a goodness.

Lauren Herold: Thank you. That’s a beautiful way to end this conversation and also I feel like I needed to hear that today. So, thank you for saying that.

Alex: But see, this conversation is that, Lauren. It’s like, I see you. I heard what was happening in your life. Thank you for listening to me so much about my film. It’s simple, but we can and should and have to do that for each other all the time right now.

Bodybuilding Icon Bev Francis Reveals Real World Behind ‘Love Lies Bleeding’

With the release of Rose Glass’s new film, Love Lies Bleeding, this month, I think it’s safe to say that female bodybuilding is having a moment. By the mid-1980s, which is when the film is set, female bodybuilding was just beginning to crest the peak of its popularity. Gyms and health clubs were opening up in every corner of the U.S. and competitive bodybuilding federations were finally including women’s competitions. When George Butler’s 1985 documentary Pumping Iron II: The Women premiered at Cannes, it became apparent that the niche sport was becoming a little less niche, at least for a little while.

The film introduced the world to professional female bodybuilding and, in turn, introduced the world to the women — both seasoned professionals and the newcomers to the sport — who compete. One of those newcomers, Australia’s Bev Francis, an accomplished professional powerlifter turned bodybuilder, took the bodybuilding world by storm. Francis, who was the most muscular competitor in the film, had a physique that people weren’t used to seeing in the sport and, subsequently, didn’t know how to handle. Following the release of the film, Francis would become one of the biggest stars in bodybuilding, not because of how many times she won but because of how jacked she was and because of how she kept competing, despite what people thought about her.

As someone who’s obsessed with strength sports and strength sports history, I was immediately enamored with Francis’ athleticism, tenacity, and “Say whatever you want, but I’m doing me” attitude. I reached out to Francis to see if she’d be interested in talking about her career, her involvement in the film, and her future in strength sports, and, thankfully, she agreed.

Our conversation was long and had many diversions — mostly about the excitement of getting stronger! — but here you’ll find the highlights so you can get to know this legend a little better.

Stef: I think our community of readers might be learning about you for the first time, so I think it’s good to start with the basics. You began training in track and field in college, and then you branched out into powerlifting after. And on top of that, you were going to school to be a physical education teacher. How did you get interested in sports in the first place, where did the obsession begin, and what were your early experiences playing sports like?

Bev: I’ve just always loved physical movement. I started with dance, which was the first organized thing I did, because my mom was a dancer when she was young. And my sister, who is my closest sibling in age, but still seven years older than me, was in dance class. My mom used to take me along in the little stroller, and as soon as I could walk, basically, I was dancing on the sidelines, and I obviously loved that. So Mom enrolled me. I was like three and a half, four, that’s when I started dance. It was ballet, classical ballet, tap, and some ethnic dances. We did things like Highland Flings, Irish Jigs, and Polish mazurkas, and all those things. I just loved all that, and I continued doing classes until I was about 15.

Once I was at school, I was playing any sport that was available. I was always good at physical education, I was always a fast runner, I always had really good hand-eye coordination, and I was just good at sports. I was always doing something athletic, physical. And at school, I really loved track and field. I wasn’t fabulous at it, I was fast, but not the fastest. I could throw well, but not the furthest. I was always up there, but not the best at anything. So by the end of school, I had to choose a career. And again, I’m talking graduating in 1972 from high school, so careers for women, if you were going to be out and doing a job, you had to wear stockings, skirts, and heels. That wasn’t me.

So, I chose the only thing I thought I could wear casual clothes doing, and also that I was interested in, and that was physical education teaching. And my family was a bunch of teachers. I mean, Mom had been a dancer, but she taught dancing after she stopped. My father was a teacher, one of my brothers was a teacher, and my sister was a teacher. It just ran in the family. And it was also a way for me to get a tertiary education, because I could get what’s called in Australia a studentship. The education department is run by the state government, and they gave scholarships to do the teacher training, and you had to teach for a certain number of years. We didn’t have enough money for me to go to university, but with that studentship I could.

It was perfect. I got paid to do a course that I wanted to do, and get into a job that I wanted and felt comfortable in. And when I went to university, you did every sport imaginable in your physical education course. Ones that I’d done before, and ones that I hadn’t. And while I was at the university there was a coach, he was a world renowned coach, and I started training with him just for fitness. I told him straight out, “I’m not an athlete.”

Stef: Wow, you were so wrong.

Bev: Yeah. And I wanted to learn from him, because as I said, he was a genius coach. He was the coach for Roger Bannister, the first four-minute miler. Franz Stampfl was his name. And he was the person who saw something in me. He thought that I could be better if I trained specifically for throwing [shot put], and told me to do that, I would have to weight train.

I said, “I’ll do anything that I have to learn.” So he started me off with weight training, and I found my niche. I just got stronger and stronger, and I loved it and just fell in love with the whole idea of strength training and everything that went with it. My throws got further, my sprinting got faster, my jumps got better. I saw that everything was helped by strength, and that flowed into life…your confidence, everything gets better as you get stronger. Strength just became a lifelong love for me.

Stef: I know in your powerlifting career, you broke records. And not only that but you were able to get totals that people are still aspiring to lift right now. You mentioned your coach got you into weightlifting, which I think is kind of common for people who played other sports and then become strength athletes. Can you tell me a little more about that training transition?

Bev: The two main lifts that he regarded as essential for power training, for the throws, were the squat and bench press. They were the two basic movements. And of course, you’ve only got to add deadlift to that, and you’ve got powerlifting. So, it was a little bit later that we did some deadlifting, as well as curls, leg extensions, lat pull downs, and everything else. But the basis of the training was massive amounts of squats and bench press.

Stef:

What drew you to eventually competing in powerlifting in the first place? Can you talk a little bit about your experiences as a female powerlifter in the 1970s and early 1980s?

Bev: It was actually very easy. I didn’t choose powerlifting…powerlifting chose me. My teammates [the other women Stampfl trained alongside Bev] and I were getting strong, and we were breaking shot put, discus, and javelin state and then national records. We were getting publicity in the papers over two years, and one of the things the articles were saying and we said is, “We’re stronger. That’s why we’re breaking records. We’re doing all this lifting.”

It was probably in the end of 1976 or early 1977, the Powerlifting Association in Victoria, that’s the state in Australia where I live, contacted our coach and had seen the articles in the paper, and they were trying to get women’s powerlifting going. They called up our coach and said, “You have some strong girls. Would they like to compete in a powerlifting meet?” They had to explain what a powerlifting meet was. And we thought it sounded like a fun activity to do. The three of us went along, and we all broke the Australian records. And there were no world records ratified at that time, but they informed me that my lifts were the best on record in the world for my weight class. So it was like, “Okay, this sounds like the sport for me.”

After that, I just started winning. I won every contest that I went into, which is kind of nice when you find you can win something. That’s how I got into powerlifting. And I stayed in it until I’d already moved to the U.S. I did my last two contests for Australia while I was living in the US. And then by that stage, I’d done [Pumping Iron II: The Women], and the movie had been released.

I got a couple of injuries, and I’d won six world championships, and this bodybuilding thing was all around me. And people were saying, “You can’t do it.” At the same time, I had all these fans saying, “You’re the best. Come back and do more.” But I felt like I’d conquered the world in powerlifting, and it’s hard on the body to keep going year after year at that level. So bodybuilding, even though it’s hard, it’s hard in a different way. It’s just pain, but it’s not that heavy. It’s pain of reps after reps and the burning and the intensity, but it wasn’t putting that heavy load constantly on my spine. I thought, enough with powerlifting, and let me give my full attention to bodybuilding now, and show all these non-believers that a powerlifter actually can sculpt their body and become the best bodybuilder in the world.

Stef: Your bodybuilding career began with that invitation from George Butler, right?

Bev: Yeah, because I had no intention of getting into bodybuilding. When he asked me to do the movie, they wanted that extreme body to give the movie some punch, and it sure did. I mean, if you’re asked to be in a movie, you do it. I was an amateur athlete! A schoolteacher! A world-class athlete, but still, it’s a very exciting prospect to be asked to be in a movie. And it came at a perfect time because I had partially torn my Achilles tendon, and recovery from Achilles tendon surgery is very long. It’s basically a year. I knew I was going to be out of action from throwing, from running, from even squatting, because I didn’t have the flexibility after the surgery. My ankle was pretty much locked, and I had to gradually get the flexibility back.

My training was completely different. And I had this opportunity, and my coach was like, “Yeah, take it.” So that’s what I did. And as I said, I threw myself fully into it. I had to learn how to diet and everything, because I had no idea how to diet. And also, I had no respect for bodybuilding at the time. Bodybuilding doesn’t take the effort of running, jumping, throwing, lifting. I thought it’s not athletic, it’s just posing. Of course, I soon learned the training for bodybuilding is really, really tough, and especially when you throw in reduced calories. My respect for bodybuilding grew. And as I said, I was coming to this stage where I was getting injured, and it was getting tough on my body. I preferred to retire while I was ahead, while I was a winner.

Stef: You were originally doing both, and then you made the official switch, right?

Bev: That’s what I did. 1983 was when I tore my Achilles tendon and couldn’t do anything. And that’s when the movie came along, so it was perfect timing. I was still able to do the World Powerlifting Championships in 1983, and in 1984, I moved to the US just before the World Powerlifting Championships that year. During that time, in 1983 and 1984, I was doing bodybuilding, and I was doing exhibitions. And after the movie wrapped, I came back to contests in 1986. That’s when I started bodybuilding and no powerlifting.

It took me three years of training to reshape my body, to get that V-taper, to bring my waist in, to bring my back out, to bring my shoulders up, to do the things I had to do for bodybuilding.

Stef: How would you describe your experiences in the bodybuilding community? I’m interested in how it was interacting with other bodybuilders, even your direct competition.

Bev: My track and field group was a family and we still are. And that was one of the genius moves of Franz [Stampfl], creating a group dynamic and to have a group that trains together. But with bodybuilding, I was in my gym, and everybody else was in their own gym. It’s rare to have someone who’s a competitor who’s in the same gym, especially at the professional level, because they’re all over the country. For example, in the movie, Rachel [McLish] and I were cast as direct antagonists, but we’d never met. And, in fact, we did not have a conversation during the time of Pumping Iron II. We never spoke.

However, after the movie we were both called for guest posing, and sometimes we went to the same place. We spoke, and I actually wrote her a letter just to tell her I had nothing but the greatest of admiration for what she’d done for women’s bodybuilding, and that it was certainly not my choice that we were cast as enemies. And she responded very positively to that letter. At one stage over the next couple of years, when I had to go to where she lived in Palm Springs for an exhibition, she had called the Gold’s Gym there and left six messages for when I got in there for me to contact her and her husband. Steve [Bev’s former husband and training partner] and I ended up going and meeting them for lunch, going to their house, and going out with them. And she’d visit our gym in New York.

I also always got along really well with Cory Everson, she was Ms. Olympia when I finally came into Ms. Olympia in 1987. She’s kind of goofy like I am, we both like to goof around and have fun, and she’s very down-to-earth. We just loved each other from the time we met, and we stayed friends. I still have cards that she would send me before the contest saying, “You and me first and second.” Or, “Equal first, let’s beat all the others.” And, “I’ve got an idea, let’s mess around in the posedown.” Which we did. I would jump in front of her and pose, and she’d pick me up and push me aside. The audience loved it. We’re still friends today. Leanne [Bev’s partner] and I went and stayed at her house in LA a couple of years ago on our way to New York.

But as I said, it’s harder in bodybuilding because you don’t have a group that you train with every day who you also compete with. The people I train with every day in the gym are just regular people. Steve was my training partner, and other people in the gym would come to the Olympias and support me.

Stef: I’ve learned a lot about how much sacrifice and hard work it takes. I know you’ve spoken about how much training you had to put into it, and on top of that, being a bodybuilder can be really expensive. Given how much you had to give to the sport, what kept you coming back year after year?

Bev: Well, I mean, it’s pretty simple. I wanted to win. That’s pretty much it, I wanted to be Ms. Olympia. I mean, I was really happy that I won the World Championships, because I was world champion in two sports, that’s pretty cool. World champion powerlifter and world champion bodybuilder. I’m in two Hall of Fames. I’m in the Bodybuilding Hall of Fame and the Powerlifting Hall of Fame, which is pretty cool, too. But yeah, I wanted to win.

I mean, and that was the thing that allowed me to do the part of the training that I didn’t like, the part of changing, becoming more “feminine.” I mean, it’s nice to have someone actually say, “You look pretty.” Or to look at pictures and go, “Wow, you actually look gorgeous in this picture with the makeup.” Because I never used makeup, and I had short nails. I looked like a classic lesbian, even though I wasn’t a lesbian. I was straight as a ruler until just a few years ago.

For years, I tried to make sure that my hairstyle and my makeup appealed to the judges. Even my body, I had to bring it in, I had to lose muscle every year. I had to diet, not only to lose body fat, but to lose some muscle, to bring my body into more feminine lines. Because as it’s been quoted at and many, many times, the rule book states that judges must remember they’re judging a female bodybuilding competition. So I had that thrown at me.

Stef: We’re still having these conversations about what female athletes can and can’t do, and I think that that’s in every sport. People often talk about how you were ahead of your time. How do you feel about that? What does that mean to you?

Bev: I’m very proud of that now. I certainly didn’t go out to change the world. From the time I was a little kid, I wanted to do what I wanted to do. I was a very determined little bugger. I was a difficult child, and I was a complete tomboy, as they called it. I never wanted to be a boy, I wanted to be a girl on my own terms. I wanted to be a strong girl, I wanted to be a brave girl, I wanted to be a smart girl, I wanted to be an achieving girl. And I could see no logical reason why any of that shouldn’t happen, I couldn’t see any reason why I couldn’t do anything that any guy could do.

And that’s just how I thought from the time I was little. I mean, I was the perfect client for Franz because he was totally for women being so much better than they were, and he believed that the key to it was women getting strong. He said, “Women are nowhere near their potential, and the one thing they can do to increase their performances is weight train and get strong.” And I didn’t see limits. Just, How strong can I get? There was no limit, and it was very encouraging.

My family was good about it. I had a very traditional family, Dad was a school teacher, Mom was a homemaker. She cooked, sewed, knitted, crocheted, preserved, made jams, all the things that a really traditional housewife would do. And Dad would never let her work, even though we had five kids in the family and were struggling on one salary. Very traditional in that way. And yet, I mean, when I was a kid, always, I wanted to go rabbit hunting with him, shooting. I would go chopping wood with him and help in the backyard when he was doing his concreting and everything. All the boys had to learn how to cook basic meals and iron their shirts. And it’s like, “You’ve got to learn to take care of yourself, and you’ve got to be able to do everything.” When I started lifting and getting strong, Dad was just proud, his strong daughter. And Mom, the only concern Mom had was, “Be careful, make sure you warm up right. Don’t hurt yourself.” That was all. Otherwise, they were proud as punch of me. I had the support of my family, and I was very, very fortunate, because so many people, when they’re going into the world to do what they want to do, they don’t have that.

I guess I was never scared, I was just, “Fuck everybody.” But I had enough support that I could do it. And women should be allowed to look whatever they want to look like, and do whatever they want to do. God’s sake, men do. I just wanted that freedom. I wanted freedom for myself and for me to feel that I’ve helped free other women, or give an example of what you can do and be happy about it. That has made me feel good.

Stef: I think that that’s interesting, especially in terms of something like female bodybuilding, where gender presentation is heavily policed. I can see how you coming in during that time and saying, “No, I’m going to look this way, and I’m still going to compete. And you’re not going to push me out until I say I want to be out.” That is extremely important. I have a feeling that it impacted not just female bodybuilding, but also just female sports in general.

Bev: I hope so. I mean, when I was competing, Martina Navratilova was a very muscular woman, and she was the only other one that I really looked at who looked… Not similar to me, but looked like she didn’t give a fuck what people thought of her. And I liked that. But beyond that, I didn’t have any role models. I just wanted to do what I wanted to do.

Stef: It’s important to just go forward anyway. I imagine that’s how you kind of coach your clients now.

Bev: Oh, yeah. I mean, you’ve got to decide what you want. I tell kids, with social media and everything the way it is these days, I tell them that, if you’re into sport as a career, first of all, make sure you’ve got a backup. Because unless you’re the best in the world, there’s not a lot of money in it. But if you’re into sport as a career, don’t go into it because you think you’re going to be famous or rich, don’t go in it for those reasons. If you are going into it for those reasons, you’ll never be able to put in the work that you need to be the best in the world. The only way you’re going to be able to put in the work that you need, is if you love it. If you’re willing to do that work for nothing, even pay to do the work. If you’re willing to pay to do the training and to go through what you have to do to do your sport, that’s the only way you’ll ever be able to put the effort in to make you the best that you can be. And that’s all you can be, the best you can be. If you don’t love it, if you just like it, but you think you’re going to be famous, then you may as well go get another degree right now. Go for something else, and just do your sport for fun, because you’ll never be on top.

Stef: That’s a really good point. And could be said about a hundred things outside of sports, too.

I’m going to switch gears a little bit. When I first started learning about who you are, I didn’t expect to find out that you’re now in a relationship with another woman. I know you’re not into labels, so I’m not going to use any. But I have to say just personally as a queer person, it’s always a little bit of a relief to find out there are people like you involved in the things you love to do. So, finding out about you, and other strength athletes who are openly queer or trans, like Rob Kearney who is a very famous gay strongman and Laurel Hubbard who is a trans woman who competed in the Olympics for the U.S. lifting team, is helpful in feeling that there’s a place for us in the sport. I know that you just kind of kickstarted your powerlifting career again and technically, you’re not in the kind of profession where you would need to come out. But I’m just wondering how you feel about being a queer athlete. Do you feel proud to be a queer athlete? Does that ever come across in your mind that you are now part of our very small pantheon?

Bev: If it had been 30 years ago, it would’ve been very awkward, because it wasn’t accepted. I hate categories, I don’t like names for things and categories. And it’s just that people are different. And there’s this whole black gray, dark gray, lighter gray, white in both gender and sexual preference. And I don’t know, I don’t like it being chopped up so much. I’m very happy that it’s a much more accepting world. But as I said, personally, I don’t like all the labels, I don’t see a necessity for them. Other people do, and that’s their choice. So what am I? I’m a woman.

Stef: You don’t even have to define that if you don’t want to, I’m not asking that.

Bev: Yeah, no, but I’m happy to. I’m a female who has a girlfriend, has a female lover, and I have had male lovers in the past, and that’s about it.

Stef: Listen, you’re not alone. That’s pretty common.

Bev: Well, that’s just it, I know. And I love the diverse world. Wouldn’t it be boring if everyone was the same?

Stef: Yes, it would be. And yes, it is accepted to a certain degree. I live in the U.S., so I don’t know the differences between the U.S. and Australia. But it is accepted to a certain degree, and there’s a lot more freedom now to a certain degree. But I still think there’s a lot more change that needs to be made, obviously.

Bev: Absolutely. Yeah, I was going to say, it depends what area you’re in, it depends what town you’re in. I do think the LGBTQ community is a fun community to be in because they’re more open and accepting of differences in so many ways. I really like being in that community. I like being queer.

Stef: Yeah, me too. All right, last question. So, like I said, you recently jump started your powerlifting career again in 2022. And you broke records again, because you’re older.

Bev: Yes, it was the age group as well as the weight class.

Stef: So, what’s the future? What’s your plans? Are you going back into that now?

Bev: I think I will. After that year I was feeling good and strong, but the next year, Leanne, my partner, wanted to do the Great Victorian Bike Ride. It’s at the end of the year, and it’s a five-day bicycle ride, and you camp on the way. It’s over hundreds of miles, and you’re riding about 70 miles a day. I had to train for that, because I’m not an endurance athlete, I’m a power athlete. I’ve been a sprinter, a shot putter, a powerlifter, and a bodybuilder. I’m not a long distance runner or a cyclist, so I really had to train for that. You can’t train for bike riding, ride miles and miles, and then come and do a heavy squat workout. So, I lost some of that strength over that year, and I had a couple of bad bouts of bronchitis and COVID, which knocked me around a little bit.

I’m just building back up now. I just turned 69, and I’m hoping I can wait until next year when I’m 70 and go into the younger part of the age division and compete. Try and break maybe some records in that division, also. I really would like to go back and try a little bit of shot putting again, but I have to get a little bit more spring in my legs before I go for that. So yeah, I’m not ready to lie down and die yet.

I had always wanted to do a marathon, and that’s what I said when I was young. I wanted to start training when I was 40, I’d put 10 years, and at 50, run a marathon. But during those years, my knees deteriorated rapidly. I had six arthroscopic surgeries, three on one knee, three on the other, and then finally had two full knee replacements. My legs took a battering in terms of losing strength, losing snap and power. I’ve also had chronic Achilles tendon problems my whole life. And if I run too much, my Achilles pain flares up. I just decided that, unfortunately, that dream probably won’t ever come true. That’s why I was happy to do the bike riding. At least I did the Great Victorian Bike Ride, which was to me quite an accomplishment.

Now, I’d like to go back into more powerlifting events and see what I can do.

See Bev Francis in Pumping Iron II: The Women now available on YouTube.

“We’re a Surviving Sort of Species”: Venita Blackburn on Grief and How We Live With It

feature image photo of Venita Blackburn by Virginia Barnes

Sometimes someone is like, here, read this novel about grief, and you’re like yeah, I know about grief novels, and you read it, and it’s devastating and heartwarming in all the ways a grief novel purports to be, and you walk away saying yes, it’s all very clear, that was most definitely a grief novel. Other times someone is like, here, read this novel about grief, and you’re like yeah, I know about grief novels, and then that novel is Dead in Long Beach, California by Venita Blackburn. How to describe this genre-defying, mind-altering, utterly arresting story about complicated families and fierce love and the losses that accumulate over the course of a life? Saeed Jones said, “Your wig is going to fall off no matter what you do,” and that’s just the truth.

Dead in Long Beach, California follows graphic novelist Coral, who thinks she’s stopping by her younger brother’s apartment for a visit and instead finds herself dealing with the aftermath of his suicide. In the haze of grief that settles after his body is taken away, Coral, understandably, finds herself unable to cope — so she takes her brother’s phone and begins to assume his digital presence. I’m talking text his daughter, make plans with his maybe-girlfriend, make the man an Instagram kind of assume his digital presence. This novel is, of course, soul-crushing. It’s also, sometimes, quite funny. It’s the story of one woman’s mental breakdown, it’s a lesbian sci-fi saga, and it’s a tender exploration of how humans struggle to process unimaginable loss. It’s upsetting and absurd and, at times, you don’t know where it’s going to take you, but it always sets you down right where you need to be. It’s a grief novel, sure, but that’s not even the half of it.

Listen, I could go on and on about the rollercoaster that is Dead in Long Beach, California, but this is not a review, and I was lucky enough to sit down with Venita and talk all things debut novel — so I’ll let her tell you the rest herself.

Author’s Note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Daven McQueen: Starting out with a classic first question, what was your inspiration for this book? Where did you come up with the idea?

Venita Blackburn: Well, I had the idea for the interior parts of the book far earlier. The original title was “Lesbian Assassins at the End of the World.” That was sort of the big vision. I was kind of going to do this wild, epic kind of high fantasy sci-fi sort of thing with a small tether to modern existence and set in California in different time periods and all that kind of jazz. But I also tend to look into a lot of my older work and there’s always something that I’m not done with — concepts, characters that are still nagging me and rubbing against my psyche. I have to go back and sort of figure out what it is that’s still bugging me. There’s a few stories from my second collection, How to Wrestle a Girl, about dysfunctional maternal situations and femininity and sexuality, and I carried a little bit of that over into Dead in Long Beach. Then I started to deal with why I was trying to do this high fantasy sci-fi kind of world that is so far away from the things I know. I found it’s because of these profound senses of loss, this world of transformation and this feeling that we cannot go back to what we used to be and to the relationships we used to have.

I wrote most of the book during the pandemic, this huge moment in time — and we’re still in it. We’re still in this transformative state where we have to make a lot of big choices about who we’re going to be and what things we’re going to carry forward from our past into our future. If we’re going to try to cut a lot of them off, what will that mean? Who will we be after that? And there’s also the sense of denial about the nature of our history, about who we are as individuals — capable of terror, great terror, and also great love and compassion. And this idea that we haven’t quite navigated that sense of our own selves in a lot of ways. That’s when I started to go into the real heart of the story, the frame story, that’s set in the real world with a character who’s lost her brother and is unable to psychologically process that. That became what I knew was going to be the biggest story. I did a lot of trimming of the big fantasy in order to make room for what I would call a horror story.

It’s a little funny, but it is a tragedy. It is emotionally taxing to think about it, let alone to have to produce it over and over again on the page. I started to realize that I was distracting myself with the other story because it was fun and weird and sexy. That’s why the story wasn’t coming out.

DM: What you just said, describing the book as a horror — that’s something that really struck me as I was reading. It’s like, the hairs on the back of my neck are standing up, there’s this sense of claustrophobia. At the same time, like you said, you do have this sci-fi story interwoven throughout and this narrative voice that is non-traditional and extra-human. I’m wondering how you’ve come to think about the genre of this book, if there’s a way that you feel like you define it.

VB: The only kinds of genres I tend to think about is sort of, is it nonfiction? Is it poetry? Is it fiction? How close to reality are we going to get? Within the different breakdowns of fiction, I have no idea what this book is. Is it literary fiction? Is it fantasy? Is it sci-fi? It is this kind of strange anomaly in terms of genre. I would definitely call it a horror story, but that’s just because this is what I would classify as horror. I grew up watching traditional horror movies with my mom when I was a kid, very young, like five or six years old. She was just into it. She loved ghost stories and psychological trauma stories, and now those movies have a sense of comfort for me. Men behaving like monsters, dressed up in costumes, that’s almost cute to me versus, you know, what I think is truly terrifying. The truly terrifying things are the stuff that we can’t see. The stuff that’s going on internally, the breakdown of the mind, the loss of people that you love. The stuff that happens in real life, that’s horrifying.

DM: I’m also a big horror fan, and I’ve been watching them since I was really young, so a lot of the traditional scares feel sort of…

VB: Goofy?

DM: Yeah, goofy!

VB: They’re goofy. They’re silly! And I love that you mentioned claustrophobia as an element of horror and isolation. This particular character is dealing with that kind of internal claustrophobia. The world seems very big to her because of the life she’s living, tangential to fame in Southern California, which has that vast feeling. We don’t do a lot of high rises here, so the landscape is kind of low to the ground, too. You can sort of see the expanse of nature; things feel kind of open. But on the inside, she’s not connected to human beings in a way that she ever will be again. She’s gone through this complete separation and she’s unable to speak it. And that creates that other layer of claustrophobia where she is kind of bound in her own brain. No one else is in there with her except for the voice, which isn’t her own voice. That collective hive, that’s her only comfort.

DM: I do want to talk a little bit more about this hive voice. The first-person plural is so rarely used in fiction, and I’m curious about how you decided to use it.

VB: I love the first-person plural. I think it’s a beautiful voice with a sense of authority over the content. That’s sort of the trick that it brings. Every POV has its own little tricks. The first person is limited to just one person’s brain, comes out of their voice and their perceptions. You can’t go beyond it. You don’t have that sort of god-like aerial view of the world. The first-person plural allows you to get that, but also to have that god-like sense of everything else, because you always have more than one, the “we.” I think it’s just magical, the way that authority immediately happens. I call it the sort of natural sense of peer review built into the voice. It’s also a sense of community and a sense of belonging that’s built into the voice. And that’s exactly the thing that this character has lost, right? Her family is now broken, and her sense of self is broken too. She needs something that’s going to keep her tethered. In this moment, because she is so isolated, all she has is her own brain. This is the voice that she’s actually created for her own artistic purposes, and it’s the one she falls back on in order to navigate her way through this terrifying moment in her own life.

DM: It is really interesting the way that the voice does have this sort of collective feeling. There’s some level of warmth and community there, but we’re looking in on Coral who is so increasingly isolated and inside her own brain. I think that contrast really contributes to the sense of horror.

VB: Yeah, and I tried to create a sense of momentum as well, going forward, where it’s getting worse. You know, she’s got to make progressively worse choices. That’s just the rule. That’s the fiction part of things. Things’ve got to get worse and worse and worse and worse until they can’t anymore. But the voice has a sort of steady attitude about it all. Even if it’s terrible, that voice says, no, it’s beautiful. It’s beautiful and horrifying. Let us practice it. Let us, you know, revel in the marvel of this maliciousness. It’s this juxtaposition of all of the good and the bad and the things that make up humanity and make up who we become in these crisis moments, too. The beauty and the violence, the sadness and the celebration.

DM: Because of the voice, as much as the book is really focused on what’s going on inside Coral’s head and this experience of her life unraveling after her brother’s death, there is also this broader unpacking of what people are and why they make the choices they do. There is sort of this sense of doom around that, but at the same time the collective voice is, saying, “Everything’s going to be okay.” You saying you wrote this during the pandemic makes a lot of sense; I can see a lot of those feelings present there. I feel like it’s also really speaking to the present political moments that we’re in and the increasing sense of doom that a lot of people are feeling. But at the same time, the voice is engaging with some level of hope. I’m curious about how you think about that hope-doom balance in the book and how that connects to the world and humanity more broadly.

VB: I don’t believe in hope. But I’m also optimistic. I have that kind of ancient Greek philosophy about hope, that it arrests man’s despair. It makes you stuck. It’s when you’re in a crisis moment, and instead of doing anything, you’re just sort of hoping that things work. It’s also the thing you say to somebody when you’re not going to do absolutely anything to help them. You know, they tell you that they’re sick and you’re like, “Oh, I hope you get better.” I try to remove the word “hope” as much as possible from my lexicon because it has that feeling to me of inaction. I want to encourage people to, if you see something terrible in your life, in your community, that you make an effort to change it. You don’t want hope, you want action. You want reason. You want logic and purpose. You have to have all of those things, no matter what happens in the end.

That’s sort of my personal philosophy of things. And I guess it filters into that voice as well, because technically the end has already happened. People didn’t make it, according to the voice. It’s speaking beyond humanity, and it’s doing so in a way that’s sort of honoring their presence. It’s a child loving their grandparents and honoring their ancestors, even though really, the voice is not even human. They’re just sort of data. And I think that’s kind of connected too to where we are, where the last thing that we might leave is just a record of ourselves, just our data. We’re generating a lot of it all the time, to the point where it becomes so messy and chaotic that we don’t even know how to recognize ourselves amongst all of these little echoes that we’re leaving all over the digital spaces we inhabit. I’m kind of obsessed with that idea, but not that it’s going to destroy us. I don’t think our technology will be the end of us. If anything takes us out, it’s going to be us. But I don’t even think that will happen, you know — I think we will endure. We’re a surviving sort of species. We have thumbs! We keep creating new ways for us to prosper and to survive. But we keep forgetting a lot of things. We almost encourage ourselves to not think about our mistakes in our history. That’s the thing that can keep us from progressing and keep us arrested in our own despair and suffering. Because we don’t even know how we got there, because we forgot, because we didn’t teach it to our children. We didn’t make that record. Human beings are always this way. We always make a mess. We always clean it up. We’re violent to each other. We’re violent to our children, to ourselves. And then we are suddenly capable of such compassion and gifts of love without question. That’s the thing that’s hard to record. We forget that really easily as well, especially in our age of presentation, where if you’re if you’re not online protesting for something, then you don’t believe in it. It’s only real if we see it in these small squares of digital light. That’s not the true human self either. We have to keep reminding ourselves of all the different levels and states of existence that we’re constantly cycling through all the time in order to just be.

I don’t believe in hope. But I’m also optimistic. I have that kind of ancient Greek philosophy about hope, that it arrests man’s despair. It makes you stuck.

DM: I absolutely love that perspective. I think so much of what we’re fed is just this very black and white idea of like, either you have hope for the future and it’s just so misguided or we’re doomed, everyone’s going to die, climate apocalypse in the next, like, 15 years. That, I think, removes humanity from the equation in a way. This book has a sort of reverence for humanity and what we’re capable of that I feel like you don’t see that often. I really saw that kind of undergirding the whole story.

VB: I appreciate that you saw that. And that’s also kind of how I think. I’ve been called chronically unbothered or something along those lines. I don’t know where it comes from; I haven’t always been that way. I’ve gone through my cycles of being humbled by the world, being humbled by personal loss, and having to really build a lot of good habits around self-reflection and things like that. I have a lot of causes that really affect me mentally. Education is one, homelessness is another, violence against women is another. And then all of the other things across the globe that are all connected to those same things, connected to property, to extreme wealth gaps. That all really make me mad. It tends to disturb my unbotheredness because I can see how much suffering trickles down from all of those things. I think about that kind of perpetual nature of it, how we just have these bright moments of enlightenment on occasion, and then they break. You think you have a generation of peace, then you go a little further around the world and realize, oh, there’s an apocalypse happening just there. All that keeps cycling around itself. The only thing that we can really control is ourselves, you know, save who you can save. We have to remember to stop and go talk to each other in real life, in real time and make eye contact and move through the air with each other and walk this planet because that’s the real thing of life. You have that duty to care for yourself and care for your community. That will be the best thing we can never leave behind.

DM: Absolutely. And I think this book is kind of instructive, in a way. Or, well — the issues Coral is dealing with in the aftermath of this loss, the lack of connection and separating herself from the world, we’re seeing in her how things can go wrong and, in some ways, how not to act. As I was reading, there were moments where I was like, oh my god, stop doing that. But at the same time, I was like, I understand how this feels like the only thing that she can control. She’s trying to maintain a hold on anything possible. And…I don’t know if I have a question out of that.

VB: Well, that’s kind of what I was talking about with the juxtaposition of the good and the bad, because it starts off where Coral just needs a little bit more time, right? She’s mad at the world, she’s mad at men, she’s mad at all the things that have put her into this position where she has to clean up for people around her. But then she says, I’m going to make it stop. I want to make everything calm and peaceful and not let anybody suffer for a while. She almost gives people a gift of withholding the trauma of the loss. Then it turns into this act of cruelty where she’s actually setting them up for higher expectations. She’s sort of reaching into their futures and creating the impossible with these different relationships her brother has. And that’s part of the violence. Her anger starts to manifest in other ways. She becomes manipulative, she becomes toxic, she starts to go off into the world in progressively worse ways.

Yes, it is not an instruction manual. There is no instruction manual for grieving. When it hits you, it just hits you, and you’re just going to walk through the way it does. I say in the acknowledgments that this is just one shape of grief. It will take its own form for everyone. It’s an amorphous experience and there’s no right or wrong, truly. People just, you know, we do things that have consequences and all we can manage is what happens in the before and the after. And that’s the reality. There are no solutions offered here. In some of the earlier stages of the editorial process, my editor mentioned that we don’t get a note or anything from Coral’s brother. We don’t really talk about why the suicide happens. And I said, well, that’s not the book. That’s not the point here. This is not a book about how to get over it or prevent these things from happening. These things happen and sometimes we’re here right in the middle of the crack of devastation, the crack of grief, the crack of suffering, and this is what it can look like. That was the only promise I made, that we’re going to be right there. I’m not going to give you any reasons, I’m not going to give you any solutions, but here we are.

DM: And we definitely were right there the whole time. I know your two short story collections also dealt a lot with grief and families grieving. What draws you to write about grief?

VB: You know, there is this phrase — I wonder if it came out of a Disney cartoon or something — but it’s the saying that every story is a love story. It probably is not from a Disney cartoon. But I agree with that. I think every story is a love story, but also every story is a grief story. You know, it’s about loss. It’s about goodbyes and transformation and losing things of the self. I think every story is really invested in all of those things. There are these deep connections, this deep need and desire to feel like you belong and like someone cares about you without question. Every character is trying to find that somehow. But they’re also navigating this sense of deep loss of something. It can be very small, but it’s usually on that bead of grief somewhere. I think this story falls into both. It is both a love story and a grief story. The collective voice, the thing that is holding Coral in place, is profoundly in love with humanity, and that is essential because it’s also a reflection of this deep love Coral has for her family, for her brother, for all of the people that she has been losing. I think that’s just part of my view of people, so all of my stories are going to have that. It’s going to have loss. It’s going to have love. Otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about people, in my own mind.

But I also write about this weird period of adolescence, when you’re changing into yourself as a person, figuring out your own sexuality and how you’re going to present yourself to the world. I call it adolescence, but a lot of us go through adolescence for like, 30 years. Like, I used to wear really cute, like, body dresses. I had this Victoria’s secret type style; I was a super tall, weird, kind of, you know, gangly thing. Now I dress more like a dad on vacation. I got a grandpa chic sort of thing going. And I’ve never been more myself than I am now. And that’s just the surface level. That’s still part of giving up the thing and losing the thing you thought you had. That too is built into the love and the grief and the goodbyes and the hellos.

DM: I think that’s particularly true of queerness, this idea that when you come out you basically go through a second puberty. We kind of see that with Coral’s character, the ways she’s evolved through time. We see her discovering her sexuality, her first girlfriend and all these relationships, up to the dates she goes on after her brother’s death.

VB: Those are so weird. Oh my god.

DM: Yeah, I was like, oh my god. Leave the bowling alley!

We have to remember to stop and go talk to each other in real life, in real time and make eye contact and move through the air with each other and walk this planet because that’s the real thing of life. You have that duty to care for yourself and care for your community. That will be the best thing we can never leave behind.

VB: The one thing she does that I really love is that she did not order pizza for her coworkers. I was like, I support that. I support you leaving them in this state of hunger and just walking away. Of all the bad choices she made, I did like that one.

DM: I loved that moment. When she sticks her head back in and is like, it’s on the way. There is this uncomfortable delight in all of the ways that she’s making these choices and deceiving people. You’re like, oh, god, but you’re also kind of like, that’s kind of fun.

VB: I like that you saw it that way. I do have to say that when I wrote a lot of these parts, I was not in a good place. I was in the weeds, you know, kind of delirious, tapping into the rhythm of the sounds and the voice, the scenes, and the metaphors and all that kind of stuff, cycling through that sort of writer moment. Then months later, I would go back to read them and I would just crack up. I was like, oh my god, I am insane. It was not funny on the first write through. But once you experience it in a different state, it has this other effect. And I kind of like that. I like that it could be this dark place and this light place.

DM: A lot of your work is really focused on Southern California, and I know you grew up in Compton and in the LA area. I also grew up around LA, so there is a lot of familiarity to me in this book. I’m really curious about the way you portray Los Angeles — you capture a lot of the reality of it, but there’s also this sort of dreamlike quality where it doesn’t it doesn’t feel quite real. It’s like LA in a dream. How were you thinking about the sense of place as you were writing this?

VB: I’ve heard it described that way a lot, the sort of the dreamscape of LA. And I agree with that, because isn’t LA kind of like this dream? It means a lot of things to people, even from around the world. They have this idea of it. And I think that’s more LA than the real thing. The idea that this collective vision of this place is actually much better. People think of LA as a sort of nice, clean place, you know, hopes and dreams or whatever, celebrities and whatnot. But it’s actually really nasty. It’s super old and it can be dangerous, like any big city can be. I remember once I went to a conference in downtown LA, around the Staples Center. It’s got all the usual stuff, all the sort of semi-fancy, semi-pretentious chain restaurants packed with people. The food is just like, whatever, but you know, the sidewalks are clean and it’s bright and there’s palm trees or whatever, and a nice, beautiful breeze comes through so certain times you might even also smell the ocean a little bit. You all have these different kinds of sensory experiences going on and people look stylish, their clothes are bright and colorful. Then I turned a corner and a man was there bleeding out of the side of his body. He had just been stabbed. He had wandered off from close to Skid Row and was sort of yelling, you know, I got stabbed. No one did anything. I think a security guard popped out eventually and ushered him back to that area. And I remember standing there thinking, like, look at this. We think everything is okay, everything is working out. We’ve painted this picture, and then the reality wanders back over and no one does anything. I didn’t do anything. It’s all happening within a very few seconds.

That’s LA to me. It’s a mess. It’s this sort of construction of self, but there’s something gruesome underneath. There’s people just struggling. There’s tons of debt. There’s people trying to pick their dreams off the floor. But there’s still the idea of LA pulsing all the time around them. You’re just going to work and living your life, but it’s still right up against this extreme wealth and possibility for fame.

DM: Zooming out a little bit, there’s a lot going on in this book. The genre is kind of undefinable. There’s so much complexity in the narration and the character and her experiences. What is the process of writing a book like this? How do you keep it all straight in your head and have a sense of where it begins and where it ends?

VB: That is so hard, and this is why I’m just terrified of having to write another novel. I really appreciated those early times when I was writing stories and nobody cared if I was ever going to be a writer. It was sort of just me by myself doing this thing. I could make anything happen. With this book, because it’s so long, I hadn’t written a novel like this since I was a grad student. And even that one, I reduced it down to a few pages and published that. I’m like, ah, I don’t know. I don’t know what’s going to happen here. I can’t keep track of everything in my brain the way I’m used to, because in a flash fiction story, it’s two pages. I can look at the top anytime I want to, I can look at the bottom anytime I want to, I can keep track of all the objects that I’m manipulating.