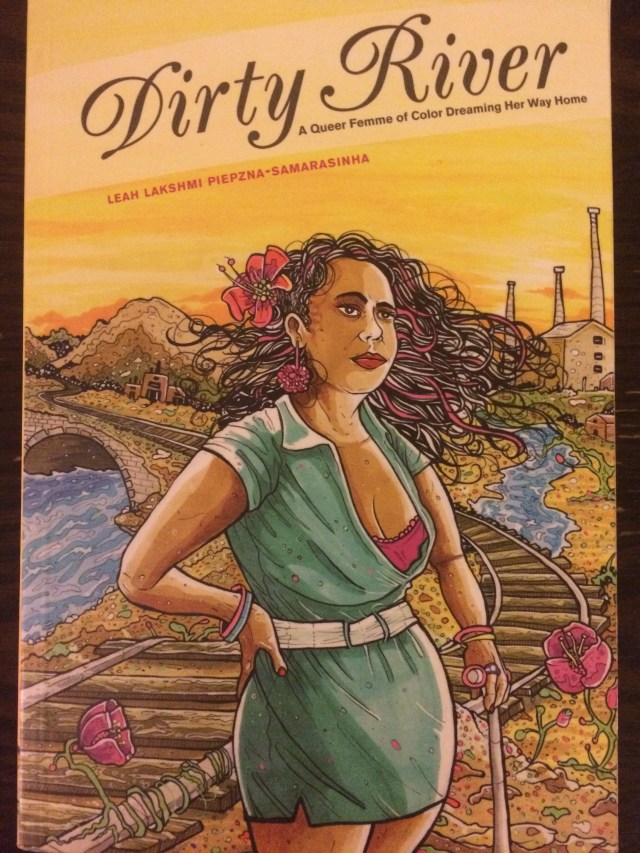

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s “Dirty River”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

As a fan of her vibrant and gutsy poetry, I was excited for Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s memoir, Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home, to come out. Much like her other work, this fragmented narrative is a survivor’s love song about finding identity and freedom.

The book opens with 21-year-old Leah running away from home, leaving her parents for Toronto with a backpack stuffed with fancy clothes, books, and a sex toy. Piepzna-Samarasinha writes gripping journey stories, and the pace picks up as the memoir moves forward. There’s border interrogation. There’s riotous activism. There’s an intense romantic relationship with Rafael, “the mixed-brown-survivor-separated-at-birth brother I’ve been looking for” — a dream that turns into a nightmare when he becomes violent. There’s poverty, illness, escape from abusive family members, and joyous reclamation of a heritage they’d denied. If you’ve ever run away from a rough situation, or wanted to, this memoir will resonate.

Dirty River is a non-chronological narrative, told in fragments. The sequences and relationships of events are not always clear, but the short sections create a frenzied energy. Sometimes the prose breaks into poetry, or diverges into multiple versions of a story, allowing parallel truths to speak. One heart-wrenching example is Piepzna-Samarasinha’s nuanced writing about her mother, who’s both a perpetrator of sexual abuse and a teacher of tools for survival. Delving beyond the written word into the senses of hearing and taste, she includes a “Healing Justice Mix Tape” track list and a two-dollar menu for a “Hard Times Survival Dinner.” This is an honest work that defies neat and tidy narratives, acknowledging that “there’s uplift, but it’s not a straight shot.”

The book shines brightest in its stories of identity. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s white mother raised her to “pass,” while her Sri Lankan father was silent and angry about the history of a family he ran from. The memoir is full of wobbly steps toward learning to “be brown,” owning her Tamil roots, and finding community among punks and activists of color. Reading This Bridge Called My Back, a young Leah realizes: “You can relate to it more than anything else you’ve read, but that’s wrong. The women in the book are that term, ‘women of color.’ You must be faking — what is that? You are just normal. And weird… Are you?” In Toronto, she finds a “place where people were talking, out loud, about a queer/woman of color feminism, culture, and community,” and other Sri Lankans are part of it. There’s a sense of triumph in her re-learning of history, hairstyles, and recipes, and finding allies to fight systemic oppression with. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s coming to terms with childhood abuse is heartbreaking, but equally important. There’s also her claiming of femme identity, associated with rituals of dressing up, navigating the streets, and owning one’s sense of beauty, as well as opening up to lust that transcends past wounds. While Dirty River has fewer sexy encounters with women than poetry collections like Love Cake (though what’s there is great), this memoir will appeal to those seeking a gritty, glorious, multi-layered story of homecoming and self-healing.

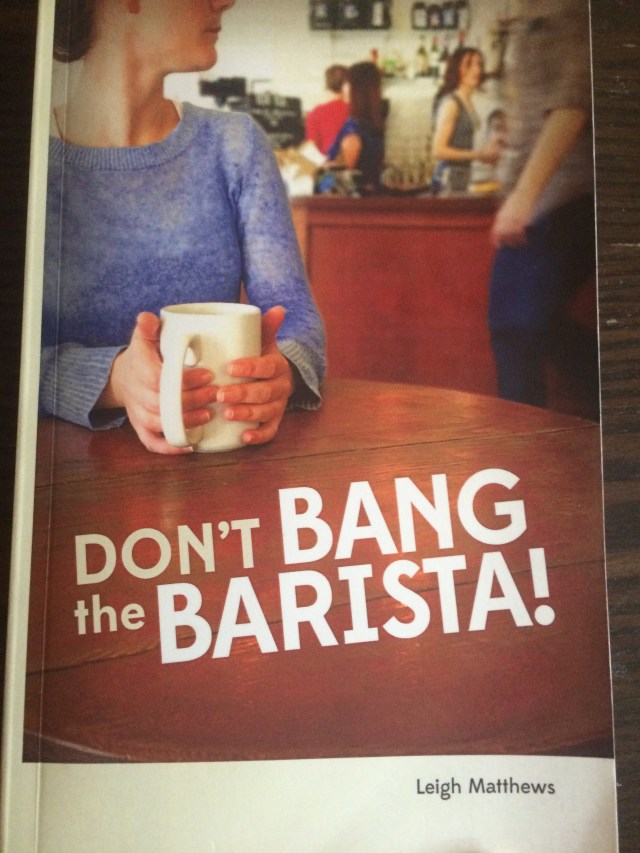

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Leigh Matthews’ “Don’t Bang the Barista!”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

Looking for a readable stocking stuffer for a dear queer or gal pal? Don’t Bang the Barista! is a good bet. It’s a fun, contemporary pulp novel full of drama, crush-worthy girls, and Vancouver subculture.

Kate is a 30-something web designer living in Vancouver and embedded in a queer social circle. She’s crushing on the barista at her favorite coffee shop, but Cass, her bad-girl friend from the dog park, warns her away. (“Kate, honey, you know the first rule of coffee-shop dating…”) But Kate and the barista, Hanna, are intrigued by each other despite the warning. It doesn’t help that Kate’s ex-girlfriend, who she hasn’t quite managed to get over, is back in town and equally interested in reuniting. But could Cass, the supposedly carefree libertine, be holding a candle for Kate? And why can’t Kate stop thinking about her?

Much of the novel’s glee is found in its witty characters, who embody a real sense of “scene.” They partake in Meetup groups, play in bands, knit, and date each other’s exes. There are Kate’s couple-friends, trying to settle into domesticity but fighting like cats and dogs. There’s the bisexual best friend, Em, who Kate looks to as a model of stability, and who suddenly needs support in opening up her opposite-sex relationship. Em’s is a unique subplot that deals with biphobia, poly dating, and changing expectations in relationships. I was really glad to see it in there, as it’s a reality that could use more representation in the book world. As for the protagonists, Cass often behaves like a jerk, and snarky, depressive Kate can be a bit of a mess. Not every reader will approve of their decisions or find their romance believable. There were times I wanted to shake Cass, and yell “Stop doing that!” or “Just communicate already!” But as someone who’s messed up just as badly, and been just as much of a jerk, I also kind of empathized. These characters are as real in their vices as the women in, say, Valencia. Animals also get their stage time: Kate’s omnipresent dog, Jupiter, is a likable character in his own right.

While there are soap-opera touches, such as Kate getting embroiled with one girl one day and another girl the next, there are also flashes of insight that elevate the novel beyond a typical romance. Kate, a British expat, has witty takes on everything from accents — “Yeah, it’s totally sexy not to have any clue what someone is saying to you” — to the relationship between pet ownership and procreation — “You can pretty much guess the age of the Labrador or Golden Retriever by how old the child is running alongside. A two year old toddler, huh? I bet you that dog is three, and a bit disgruntled.” Like any good drama, the plot’s resolution hinges on a series of improbable coincidences. However, there’s enough realism in the characters’ emotions and the minutiae of their lives to make these coincidences work. If smart, well-written theatrics are your thing, you’re in for a fun ride with Don’t Bang the Barista!

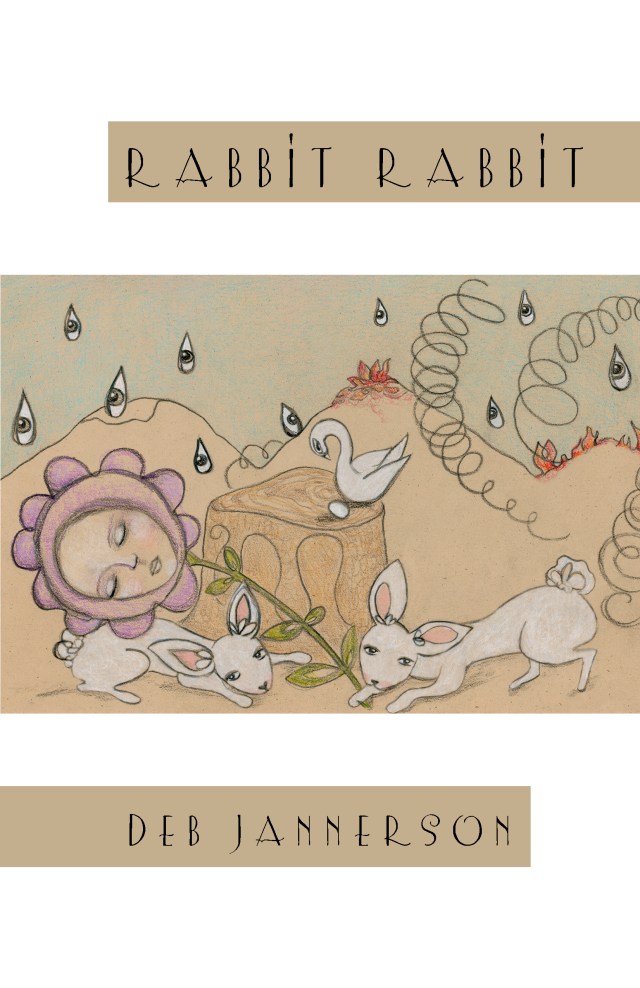

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Deb Jannerson’s “Rabbit Rabbit”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

Struggles with mental health are prevalent in the queer community. If such struggles are part of your lived experience — sinking under the weight of memories, locking your door against the outside world and praying no one knocks — Autostraddler Deb Jannerson has written a poetry chapbook that’ll grab right at your heartstrings.

In 26 slight pages, Rabbit Rabbit chronicles a personal unraveling. The free verse poems’ speaker is confessional, alluding to bruises (self-injury? abuse?) and channeling anxiety into precise images: “the tiny / tinny voice in my cotton / chest pleads for a backwards / clock.” Some of Jannerson’s poems describe life with agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder that causes people to panic in unfamiliar places and social situations, and consequently to avoid them. She chronicles this condition with detail and humor. One poem’s speaker uses nightly trips to the self-checkout as a way of avoiding human interaction, preferring a tacit form of interaction with the machine: “you know my / night habits, my / closed eyes after the attack, my / brand of sausage.” The book’s emotional landscape is complex, a real feat given its brevity. No stone of its dark terrain — whether shame, powerlessness, cynicism, or shyness—goes unturned. There’s a bit of Plath in Jannerson’s sensibility, but with less grandiosity and more immediate realism: textbooks and bottles join the acrid family members and wounds. Thoughts become goblins, and gaming metamorphoses into a panacea.

Rabbit Rabbit offers insightful treatment of the intricate connections between family and trauma. Memory is a poignant theme, with Jannerson’s speakers forgetting or reframing difficult moments. In “edible,” the forgetting is intergenerational: “each generation remembering less as it / grows, an infancy in / reverse.” Some of the poems capture the struggles for control between siblings, parents and children, and teachers and students. In “the seed,” an older character striving to make a young girl conform grows angry because “she’s probably happy.” Once again, Jannerson’s keen emotional intelligence is on display. There’s a felt sense of powerlessness in the face of memory and family influence, but the poems’ lyricism and defiance signal hope.

The collection’s language and imagery offer delights. Jannerson enjoys wordplay, playing sounds off each other (elephant/element) and exploiting the sonic texture of words (“funny bone famish”). This ability is especially on display in the witty “when you write erotica,” which describes how even the sensationalism of erotic writing loses its allure after a while. I’d love to read a longer collection from this author, with more of a narrative arc. As is, Rabbit Rabbit‘s thematic focus and snapshot-like nature works well. It’s the perfect thing to read in the comfort of your room, any time you’re longing to feel less alone.

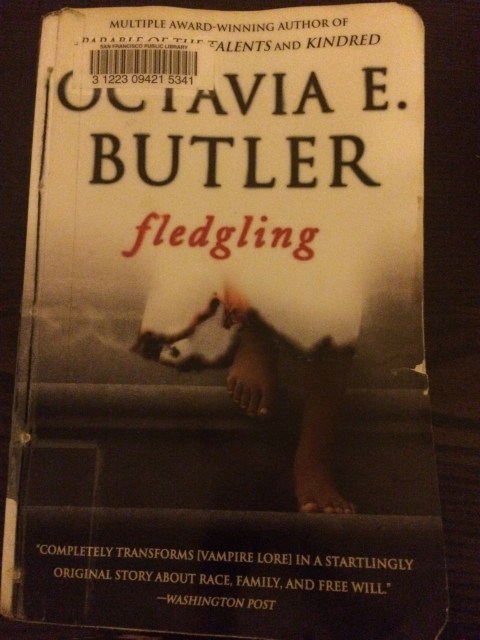

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: “Fledgling” and Queer Black Vampire Mythology

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

To bookend Halloween, I’m reviewing two thought-provoking reads about queer Black vampires. In the last installment, I wrote about The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez, the book that brought Afrofuturism and vampires together. This week I’m reviewing Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, which is both a worthy successor to Gilda and a unique take on vampire mythology. If you’re interested in seeing the complexities of polyamorous relationships interpreted through the lens of speculative fiction, or in reading a quietly queer sci-fi great’s exploration of sexual fluidity, Fledgling will be up your alley. Fledgling opens in a dark cave, with an amnesiac narrator recovering from life-threatening injuries. As Shori strives to get her bearings and make sense of the world around her, it becomes clear that she’s no ordinary person. Her instincts compel her to go out at night and hunt deer with her bare hands. Soon humans enter the mix, and her need for fresh meat (for healing) is replaced by hunger for a sympathetic stranger’s blood.

Readers learn about the world of vampires along with the protagonist. Rather than contributing to the long tradition of human-vampire conversion stories, Butler makes the vampires a separate species, called the Ina, with distinct communities and culture. One of the most fascinating aspects of the novel is their intricate relationship system. The Ina survive through symbiotic relationships with humans who share their blood and become addicted to their life-extending, health-enhancing bite. The two symbiotic species also share sexual pleasure, but cannot reproduce. Instead, Ina and their symbionts live in single-sex family units, and each family of sisters is mated with a family of brothers that they see on occasion.

But there’s little time for Shori to learn about her people. Her family was killed in the fire that destroyed her memory, and her own life is in danger. Whenever she connects with Ina who might offer help or clarity, the arsonists come after them too. Shori and her new symbionts have to figure out who’s murdering her family, and why Shori’s own death seems to be their number one priority.

Shori’s first symbiont, a rugged, good-natured young man named Wright, suspects racism to be a factor. Most Ina are long-limbed and pale, but Shori — at 53, still a child in the Ina lifespan — looks like a ten-year-old Black girl. She’s the successful product of genetic experimentation adding African-American human DNA to an Ina genome. Most Ina are allergic to sunlight, and incapable of staying awake during the day. Shori is famous throughout the Ina communities, as her extra melanin and human DNA offset these weaknesses. Depending on which Ina you ask, she’s either an asset to their species — a guard who can stay alert during daylight hours and pass on that strength to her children — or a threat to its purity.

While the threat of murder sets the pace for Fledgling, its network of relationships makes up its heart. Wright has basically been unwittingly seduced into a polyamorous relationship with Shori and her other symbionts, and is none too thrilled about it — but still devoted to Shori. Theodora, an older poet who’d resigned herself to a life of loneliness, is swept off her feet by the young vampire. Brook and Celia, the only surviving symbionts of Shori’s family, are adopted by Shori while coping with their grief. Joel, the son of a symbiont who wanted him to find a place in the human world, is delighted to find himself a “nice vampire girl.” Shori also meets a family of Ina brothers who want to mate with her when she comes of age. Shori holds the power in all these relationships, and must exercise it responsibly. For that reason, Fledgling would be a valuable read for anyone taking the reins in a D/s relationship, or navigating a polyamorous one. I would have loved to see Butler push her characters’ same-sex attractions further. Do the Ina, so flexible when it comes to their attractions to humans, ever have same-sex relationships or desires? Couldn’t one of Shori’s female symbionts have had a sex scene, as her male symbionts did? What’s there is fascinating, though. Like Butler’s masterful Xenogenesis/Lilith’s Brood trilogy, Fledgling portrays a world of symbiotic species that cross multiple barriers of attraction, for whom mutual benefit and need outweigh freedom. It’s a way of being that’s compellingly, chillingly different from our own.

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: “The Gilda Stories” and Queer Black Vampire Myth

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

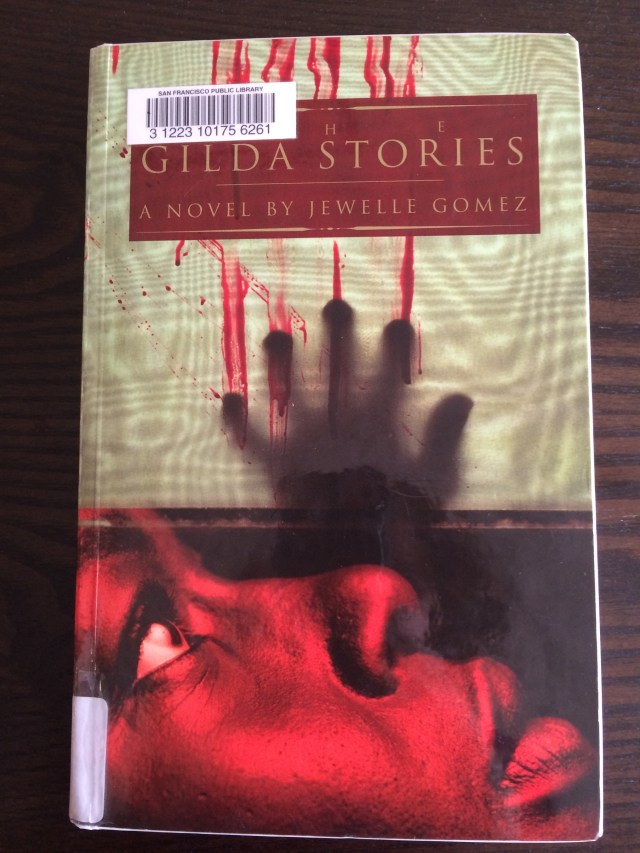

In these next two installments of this column, I’ll be doing something a little different: reviewing by theme, as two fantastic stories featuring queer Black vampires have recently caught my eye. This week I’ll be reviewing Jewelle Gomez’s classic The Gilda Stories, and in the next installment I’ll review Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, which picks up Gilda’s torch and also uses the vampire myth to tackle new themes.

The Gilda Stories was published in 1991 and hasn’t been out of print since. It won two Lambda Literary Awards, one for fantasy and one for science fiction, and was adapted for the stage. It may be a beloved classic, but I actually hadn’t heard of this book until I went nosing around… and I’m betting there are other Straddlers in the same boat. Additionally, its focus on a Black lesbian protagonist is refreshing among all the pale, wealthy men whose stories are most often told in the vampire genre, a mythic terrain ripe with possibilities. For Gomez, these possibilities span the personal, political, historic, and erotic.

Gilda’s stories begin in 1850 and end in a dystopian 2050, creating a coming-of-age story with an excitingly broad scope. Each story is titled with a time and place. In the first, “Louisiana: 1850,” a slave referred to only as “the Girl” flees a Mississippi plantation after her mother’s death. She is taken in by a white woman named Gilda who runs a New Orleans brothel. With Gilda and her partner, a Lakota woman named Bird, the Girl finds a loving home. While some of the women in the brothel are suspicious of their uncanny qualities, the Girl is drawn to them, and voluntarily joins their long-lived vampire family. When Gilda embraces death — a choice for vampires, rather than an imposition — she passes on her name to the Girl.

The new Gilda’s adventures over the next 200 years reveal an original take on vampire lore. Part of Gilda’s initiation into the vampire life is a teaching that Bird and her contemporaries hold sacred: rather than killing humans to obtain nightly nourishment, Gilda must take some of their blood and leave something in return. This is facilitated by the vampiric ability to read thoughts — Gilda can sense someone’s desires and fulfill them as she drinks her fill. If a target is craving power or love, she can give it to them in their dreams; if they’re suffering from addiction, she can embed in their minds the desire to abstain. There are other vampires in the book that kill or manipulate as they feed, but Gilda’s family of vampires considers their own practice to be an equal exchange. This is a crucial aspect of the story for Gomez, who writes in her afterword to the 2004 edition that “for Gilda to work for me and my audience, the vampyres had to break the traditional mold… if I could move the one who provides the blood from ‘victim’ to ‘sharer’ (knowing or unknowing), the nature of the power in the relationship would be different.” This exchange is certainly food for thought, and in a world where we’re all consumers, the taking-and-giving philosophy of Gomez’s vampires may, in fact, be something to strive for. Another twist is that the vampires protect themselves against sunlight and water — both dangerous to their kind — by embedding soil from their birthplace into their clothes and bedrolls. This protective device literally keeps them grounded in their own history. When the environment falls into decay in the final stories, one vampire character notes, “You and me — we’re lucky. We can’t ever forget our dependence on this earth.” Perhaps it’s these dynamics of exchange and groundedness that make The Gilda Stories’ vampire characters so human.

Gomez’s vampires offer her an opportunity to explore Black American life throughout the ages. Each story begins with Gilda interacting with someone, usually a new friend in a new decade. By necessity, Gilda moves around from place to place and job to job. Part of the novel’s pleasure is in guessing what will come next. As an immortal being, Gilda has the opportunity to explore the myriad possibilities of life that most of us only dream of. She tries her hand at farming, running a beauty parlor, singing in nightclubs, and penning romance novels. While her contemporaries relish the opportunity to travel the world, Gilda prefers exploring the U.S. and seeing how Black people live in different times and places. She holds on to memories of her mother, who was taken from her African home to the continent where Gilda was born into slavery. It should come as no surprise that Gilda’s people are important to her. In 1921 Missouri, she inspires a budding activist; in 1955 Boston, she helps sex worker friends take revenge on a cruel pimp; in 1981 New York, she joins a salon of Black artists. Readers witness changing slang, changing fashion (with pants-loving Gilda at the forefront), changing attitudes toward race and politics, and changes in women’s civic freedom. In the early stories, Gilda disguises herself in men’s clothes to walk the streets at night, and her hunting targets subtly reveal the ubiquity of male mobility.

In an interesting take on vampires’ potential for sensuality and otherness, the novel’s vampire communities are coded as queer. Gilda’s “mothers,” the original Gilda and Bird, are a lesbian couple who run a business together. The two vampire men who later become her dear friends are also partners. In fact, only two of the vampires in these stories are straight, and Gilda’s own sexuality is an understated yet important part of who she is. She finds both Black people and queer people (often both at once) to connect with wherever she goes. The novel excels at blurring the boundaries of family, friendship, need, and desire, with scenes of feeding or vampiric conversion skirting the edges of the disturbing, the sensual, and the heartwarming. Gilda’s vampire community cares deeply for its own, with members learning to live among others but maintain a necessary apartness. Its “blood bonds” supersede familial and racial bonds in some ways but not others—intersectionality is done well in this novel.

Gilda walks into the future (which is sometimes prescient and sometimes comically askew) as a courageous feminist with an enviable access to history. In conclusion, The Gilda Stories are a classic for a reason. Check this novel out to experience a masterful melding of history and dreams.

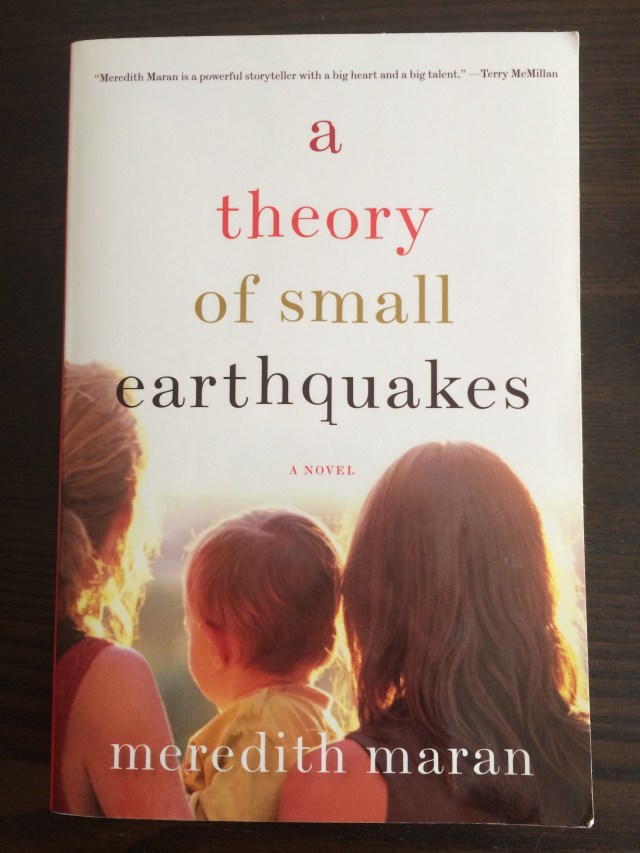

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Meredith Maran’s “A Theory of Small Earthquakes”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

When acclaimed journalist and nonfiction writer Meredith Maran chose the cover of her first novel, she selected a sunny image of two women and a baby, lending the book a beach-read feel. It was a good decision, as it led a wider audience to pick up A Theory of Small Earthquakes: a novel about bisexuality, family, and secrets, with a narrative that’s quite different from the typical work of women’s fiction.

The book begins in 1983 with orphaned Alison in college, cringing at the overzealous feminism of her women’s studies professor. She bonds with a bright, androgynous classmate named Zoe, an artist who likes her student journalism and wears fabulous outfits of “orange and lime green, polka dots and stripes, crumpled linen and corduroy and velour.” Soon Alison has a new friend… until Zoe asks to kiss her. Their relationship is idyllic at first, with self-critical Alison finally feeling accepted and nurtured: “Zoe’s love felt like a prize Alison had won without knowing exactly how or why.” Zoe and Alison move to a cottage in Berkeley, where Zoe paints and Alison takes up a writing career. But there’s a fissure in their blissful domesticity: both women want to have kids, but Alison longs to have a family the “normal way.” Thus begins a drama of paternity secrets and deliberately constructed family.

The novel has an interesting take on bisexuality and the differences between the worlds of same-sex and opposite-sex relationships. Six years into her relationship with Zoe, Alison feels a stark disconnect with the politicized, feminist queer community that her partner has increasingly embraced. She has femme invisibility to contend with: “A couple of heavily tattooed women in men’s work clothes walked by, glanced at Alison blankly, cruised Zoe blatantly, and swaggered inside.” She’s also unnerved by Zoe’s confidence in being out: “Alison was always begging Zoe not to draw attention to them in public. But Zoe just went on living as if the world were already the way they wanted it to be.” Despite her misgivings, her love for Zoe isn’t going anywhere, and the flamboyant artist pushes Alison to become her best self.

However, complications arise when Alison gets pregnant and the cause is unclear: laborious fertility treatments with Zoe, or an impulsive one-night stand with her editor, Mark. For Alison, already feeling the cracks in her relationship, Mark promises the stability that she craves. Where Zoe is both devoted and demanding, Mark is earnest and easygoing. Soon Alison and Mark are raising her son, Corey. Alison initially finds motherhood blissful: “She didn’t have to try to love Corey fully, the way she’d struggled to love Zoe, the way she still struggled to love Mark. Every time she looked at her baby, smelled him, caressed his feathery head, her heart bloomed, a cactus flower unfurling in her chest.” However, the competing demands of career and family become a lot for Alison to handle, and Zoe steps in as caretaker. An unusual sort of family is formed.

Maran handles the differences between Alison’s two relationships sensitively, and acknowledges the shock of shifting from one type of relationship, sex life, and social status to another that’s equally desirable but drastically different. Some might read in a cringe-worthy implication that bisexuals like Alison “need both a man and a woman to be happy,” but there’s something subtler than that going on, and I appreciate the novel’s acknowledgement that families can take many forms other than the nuclear norm. As Alison discovers that her seemingly simpler relationship with Mark requires the same emotional commitment she feared to make with Zoe, and as she witnesses same-sex relationships becoming more accepted in her world, Alison — and the reader — can’t help but wonder if this story would have had a different ending in a different time.

Maran’s depictions of Berkeley and its political climate across the ’90s and early 2000s are delightful. “The town was like a living museum of the sixties, populated by idealists frozen in time… The front yards she passed were unfenced, unfettered by design; they looked like they’d been planted by Dr. Seuss. Purple-blossomed princess trees, shocking pink impatiens, Day-Glo orange nasturtiums bloomed in madcap profusion amid rusty metal sculptures, toilets sprouting red geraniums, towering papier-mâché peace signs.” Her characters and their struggles are sympathetically drawn, and while there are moments they don’t seem entirely believable, they’re definitely worth knowing.

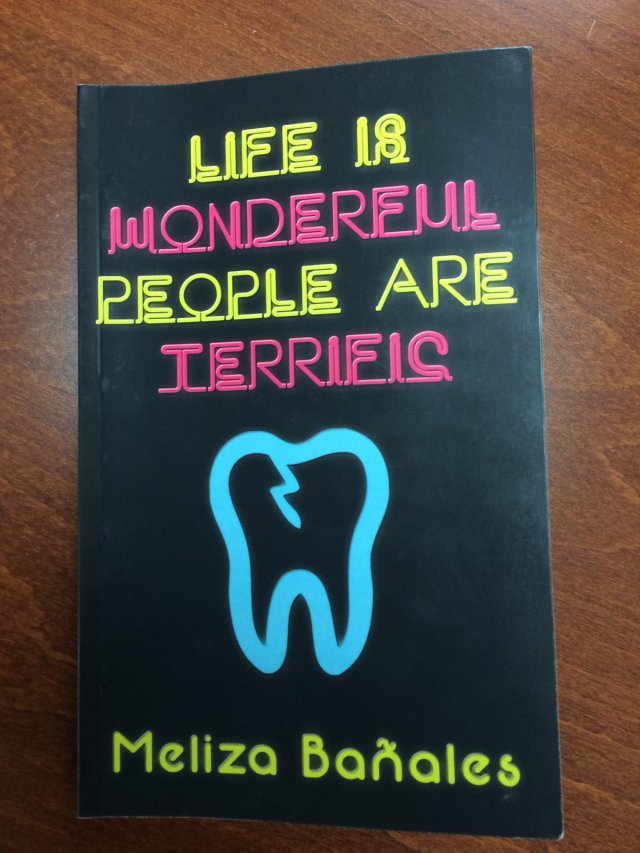

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Meliza Bañales’ “Life Is Wonderful, People Are Terrific”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

Can you resist a title as snarky as Life Is Wonderful, People Are Terrific? I couldn’t, especially when the book was written by spoken-word champion and award-winning filmmaker Meliza Bañales. Bañales has toured nationally with Sister Spit and Body Heat, published a poetry book, and contributed to numerous anthologies, and I was excited to get my hands on her first novel. It may be fiction, but this sharp and witty read bears the stamp of lived experience. Fans of bad-girl memoir, grrrls who look back fondly on the Riot Grrrl 90s, Xicanas, and working-class readers who have navigated the confusing terrains of academia will all find something that resonates here.

I’m reminded of Brian Phillips’ recent review of Jonathan Franzan’s Purity, which accuses Franzen’s novels of being “full of people who talk and act exactly as you imagine such people would talk and act in real life… And yet they don’t feel like real life.” I’ve read plenty of novels like that; Life Is Wonderful, People Are Terrific is much the opposite. The acknowledgments testify to the life experience that went into this book, which was written “through homelessness, poverty, unemployment, minimum-wage jobs, chronic illness, handicaps, abuse, four relationships, healing, recovery.” The protagonist is an 18-year-old Xicana named Missy Fuego, the first in her family to go to college. It’s worth noting that “Missy Fuego” is the author’s alter ego — Bañales’ website is missyfuego.com — rendering the line between author and character a hypnotic blur. Missy is brash, resourceful, and insecure. Her narrative voice is frank, skipping over things she cares little about (college classes, her job as a stripper) and sharing intimate details about the things that matter to her: relationships, heartbreak, and trying to figure out the rules of various social and cultural scenes she interacts with and find her place among them.

This straightforward tone is a perfect fit for the novel’s social commentary. Missy develops relationships with convincingly drawn characters from different social classes, and readers get a taste of these differences. The hippies that run her college are hilarious, and from what I’ve experienced of Santa Cruz culture, spot on. Here’s some dialogue from the Dean of Student Affairs, who confronts a drunk Missy about her dropping academic performance in the first chapter: “I feel like you’re really receiving me now, Missy. I can tell that you’re a deep person and you’re really feeling the positive energy that I’m sending out to you right now, right in this moment.” There’s Missy’s brief friendship with a group of older Chicanos, which is disrupted when a group of neo-Nazis attacks. There are her relationships with a protective punk legend she idolizes, and with a homeless drifter named Anarchy Romeo, who takes her on sex work calls with gurus who consider their services “spiritual.” There are older guys and straight-edge girls, sheltered girls and Riot Grrrls, who each play their part in initiating Missy in the ways of feminism and messy growing up. Missy stays on the lookout for pockets of home, and details about her family (brother in jail, mother who disowned her) are woven casually throughout the text. She is attentive to the unspoken codes that govern each group, sniffing out injustices, like “a Vegan cooking workshop where myself and all the other Brown and Black girls ended up doing all the cooking and cleaning while the white girls sat and ate the food,” and asking questions like “what did you have to do to get into that clique? It was more rules, more paying attention, more notes. I wasn’t sure I could keep up with all this new-ness.”

Not only does the novel paint a portrait of two towns in the 90s — New Age Santa Cruz, and a cheaper, seedier, punk-hotbed San Francisco — it also captures the realities of heartbreak. Missy’s sometimes excitable, sometimes acerbic voice makes the reading smooth as butter much of the time — except for when plot points stab you in the heart. The novel entertains with an array of of steamy encounters, including two back-to-back hookups in a gay club (“it didn’t even occur to me to be offended or feel used. Instead I felt very useful. Almost like I was doing a community service”), which introduce the protagonist to the layers of healing and hurt that can be found in relationships. The stakes grow higher as the plot progresses, and Missy finds herself causing heartbreak as much as being on the receiving end. But these mistakes also serve as catalysts for moments of friendship and triumph. As Missy gets drunk, screws things up, and gets back up again, readers feel the shift in her beliefs about what’s safe and what’s important. That first year of college is one hell of a ride.

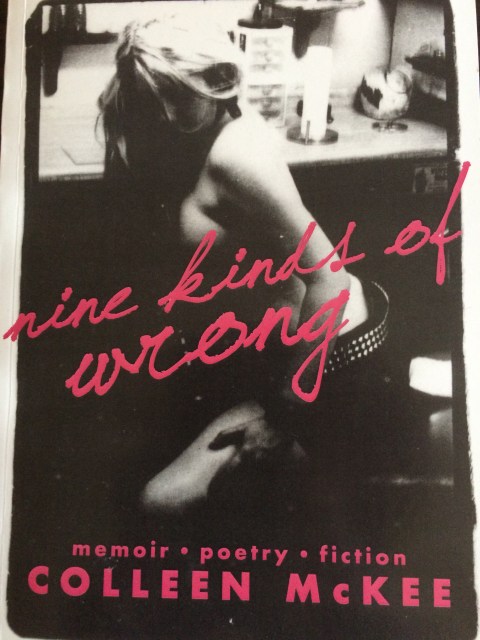

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Colleen McKee’s “Nine Kinds of Wrong”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

I’d known for a while that my colleague Colleen McKee had a book out, and one day I bought a copy from her in the break room. When I learned that it combined memoir, poetry, and fiction, I had one burning question: “Who let you do that?!” As it turns out, that’s a question she gets from other writers regularly, and non-writers, she reports, don’t seem to notice.

The book, Nine Kinds of Wrong, is wonderful, and makes a good case for more publishers to open the door to mixed-genre collections. Far from being a grab bag of odds and ends (which can be delightful in a different way), McKee’s book carries a consistent voice across genres, coalescing into a narrative of quiet rebellion, compassionate attention to detail, and elegy for a lost lover. If you’ve enjoyed other ventures into mixed-genre territory, like Amber Dawn’s How Poetry Saved My Life, you’ll love spending time with Nine Kinds of Wrong.

Queer lit, through its very rootedness in transgression of sexual norms, is a tradition of rebellion. While some queer writers have wild tales to tell of lives lived large, McKee’s stories present the rebellion of a smart introvert, which is no less compelling. Morsels of memoir tackle petty crimes like book theft, or raising hell as a vegan in Home Economics class — movingly combined with a Big Gay Crush. Readers meet a cast of ne’er-do-wells who are lovably edgy and never quite seem dangerous. That’s not to say there aren’t sinister moments. The short story “How to Make Kites” unfurls a murder scene reminiscent of Tobias Wolff’s chilling English-class standard “Bullet in the Brain.” McKee, however, is most interested in what makes her characters (whether fictional and factual) human. In one true story, a man just released from prison strokes a woman’s hair for the first time in years, an “inappropriate” public act portrayed with empathy rather than censure; in another, invented one, a “self-proclaimed psycho” waitress invites her lover to make a wish on her falling star tattoo. McKee’s prose and poetry celebrate all kinds of outsiders, from male escorts to asylum patients to passengers on the Chinatown bus.

McKee lends the same tender awareness to her writing’s urban surroundings. This is especially evident in her poetry, which notices “ground glass embedded in cement / like miniscule stars” and a tattoo gun’s “drone like a fist-sized mosquito / beating its steel-tipped wings.” She’s fond of playful subjects like gummi bears (“the gummi / dental confetti / of joy”) and ketchup (“The Germans called the tomato ‘wolf peach,’ believing one bite of the berry could turn a man into a werewolf”).

Death is another frequent presence in the book, especially the death of McKee’s good friend and former lover Miko. Much of the memoir and poetry touches on their complex connection, the relationship between a bisexual woman and a bisexual man who never got his longed-for chance to be a girl: “We wore our engagement rings on our toes. I wouldn’t say we were useless, but practicality was not a virtue in our book.” Miko’s recurrences throughout the text give the effect of a longstanding presence, sometimes in tandem with the narrator’s, sometimes apart, as when McKee commemorates him at “the filthiest bar on the street.” Like real grief, his imprint throughout the book changes but never entirely goes away. After all, as McKee writes in the ritualistic poem “taschlikh,” “Some sins are too beautiful / to ever let go.”

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Rae Theodore’s “Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

A new book is out that will speak to many the gender binary doesn’t quite fit, as well as others who have struggled to find the courage to live in ways that are true to themselves. A smart and eloquent memoir about becoming butch, Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender will resonate if you have a proud copy of Stone Butch Blues on your shelf, or listen to “Ring of Keys” from the Fun Home musical on repeat. It’s worth noting that the author, Rae Theodore, has a great blog called “The Flannel Files,” and that the book’s title page pops — a young tomboy in a mask and cape soars through the sky, fist raised up.

It’s not often that narratives about female masculinity strike a universal chord. As Alison Bechdel, and later Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori, did in the graphic memoir Fun Home and the musical based on it, Theodore has written a triumphant account of life outside “pink and blue” that seems to be clicking with, and reaching, readers outside of queer communities. While Theodore tells a very specific story, she also encapsulates a poignant sense of difference: “When you get right down to it, gender might well be the most basic external building block of man… Without it, we’re left blowing in the wind with our mouths agape. Let me guess. Is it a giant two-headed cat? …For the better part of my life, I have been the giant two-headed cat.” The book trades in the familiar — schoolyard games, family dynamics, and crushes — leading readers through a labyrinth of shame, recognition, risk, and ultimately, pride. If you want a book to help loved ones understand butch experiences and mindsets a little more, this one’s relatable tone and themes make it a good bet.

Theodore’s memoir moves in a spiral, starting with recent interactions that brought out pride or shame related to her gender presentation, then moving to origin stories that arc back and forth in time. It’s an elegant structure that makes readers feel, from the beginning, what it’s like to live “in-between,” and builds up layers of explanation later. “I see you,” the first line calls out, “looking at me with your mouth wide open and your eyes scrunched up like you just swallowed a pint of sour milk.” Readers experience the narrator’s discomfort interacting with people who aren’t sure what to make of a butch woman in their midst — memorably, it is a tiny girl “with a head of blonde curls and perfect enunciation” who causes the most anxiety — and the unexpected moments of affirmation that come from strangers who “get it” (“My grandson looks just like you!”).

Among the many sections that delve into the narrator’s past, the hardest-hitting one (for me) deals with her first wedding, to a man, before coming out to herself. She recalls a family story: “The morning that my mother was to marry my father, her Uncle Felix came to her mother’s house. Uncle Felix asked her one question. ‘Are you sure?'” Riding with her father to the church, riddled by years of questions about how the straight relationships in her life worked and how the participants knew they were in love, Theodore waited for someone to ask Uncle Felix’s question, but the question never came. Leaving Normal is full of such moments of discomfort and revelation. Some stories tell of Theodore’s childhood when she shared a special bond with her father, picked schoolyard “boyfriends” by calculating averages, and was pursued by boys who left love notes in her desk but didn’t expect her to answer them — “It’s the perfect relationship.” In another telling anecdote, a classmate presents the tomboy narrator with a macrame purse, and she becomes aware for the first time of just how much she differs from “normal.” Moments of triumph are present too. After joining a lesbian group for the first time, Theodore writes, “We felt like pioneers.”

The writing is spectacular, infused with a self-aware sense of humor. Theodore makes clever use of epigraphs and lists, such as in the macrame purse story where she lists ten horrible birthday gifts she would rather have received. Her figurative language dazzles: “The word ‘ethereal’ gets stuck in my head, and I can almost feel it melt on my tongue slow and sweet like strands of strawberry cotton candy.” This slim, gripping book is a perfect blend of subject and style. Theodore may struggle to find her reflection in the people around her, but you’re bound to find your own reflection in her story.

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Jennica Harper’s “What It Feels Like for a Girl”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

A song called “High School” used to play on the radio when I was in actual high school. The song’s narrator reminisced from the safe distance of fatherhood: “It’s kind of hard with all that sexual confusion. Sometimes you don’t know if you’re gay or straight. But what’s the difference? It’s a wonderful delusion. Most times you won’t make it past second base.” This sentiment is echoed in a more nuanced, less goofy way in one of my favorite poetry buys, a tiny little pink book called What It Feels Like for a Girl that packs a deceptively powerful emotional punch. It’s a bisexual coming-of-age story told in free verse, full of awe, lust, music, and yes, confusion.

Canadian screenwriter and poet Jennica Harper’s punchy, poignant words have been granted a Silver National Magazine Award, featured twice in the Poetry in Transit project, and gone viral among Mad Men fans. (Her poems in the voice of Sally Draper are delightful.) Harper has described herself, aptly, as a “gateway poet.” Whether or not you’re a poetry person, her plainspoken and perceptive voice will win you over.

What It Feels Like for a Girl centers on two 13-year-olds who meet in gym class: the narrator, addressed in a piercing second person that has the effect of melding our stories with hers, and precocious Angel, who guides her through a labyrinth of sexual exploration via magazines and videos. The two of them get into everything, from Playboy spreads to “Pet fantasies—horses and pups, / pregnant women peeing in cups,” driven by curiosity and a fierce determination to push boundaries: “You’re scared but dying to know.” They become the de facto dispensers of sexual knowledge in school, “warriors” informed by voyeuristic research rather than direct experience. The juxtaposition of juicy subject matter and narrative naiveté offers some fresh and wonderful insights into the sexual body: the women’s bodies have “things peek out. A ragged mountain range, / rubbery and pink. Pencil erasers,” while the men’s feature “moles popping out of holes… squat fire hoses.” The narrator is equally perceptive about performative aspects, “The language of sex, so like the language of prayer… the alpha / and the omega and the oh, oh, oh.”

Two narratives of attraction overlap for the young narrator. As she learns more about the dark sides of desire in herself and others, she finds herself drawn to fantasy men, from dead poets to an imagined family friend. This isn’t the book for you if you dislike having queer literary moments interrupted by sexualized depictions of men, as the poetry has sharp and bright things to say about different-sex desires and experiences. Outside of flash-forwards to future trysts, though, these men exist in the abstract. Meanwhile, the growing magnetism between the two girls is conflicted but concrete. They are possessive of each other, Angel thinking the narrator the “prettiest” and “kindest” girl in school while the narrator is happy to be swept up in Angel’s imaginings of her: “By noticing you, she makes you.” She, too, lays claim to Angel; in fact, “Angel” is a nickname bestowed by the narrator rather than the character’s birth name: “You made each other. You get to name her.” The worldlier of the two, Angel draws the narrator into her orbit. The relationship is both juicy and bittersweet, inflected by occasional touches and things that remain unsaid.

Madonna fandom further cements the girls’ bond — unsurprisingly, given that the book takes its title from one of the Material Girl’s singles. Angel loves the star, and for the narrator, their glamor is similar. The characters’ X-rated explorations interweave with moments from a school dance, where Angel, who “cuts through the air like it is ice and she, / a finger of fire,” pushes those explorations to the limit. A born performer, Angel toes the line between seduction’s magic and its social dangers. It’s at that point that the girls’ complex relationship starts to unravel.

What It Feels Like for a Girl is delightful for its frankness, the addictively poppy rhythm of its language, and its fascinating climate of sexual malleability — in this story, Angel is desired by everyone on the dance floor, regardless of gender. Check this book out if you want to relive the rebellions and uncertainties of your (or someone else’s) teenage years, only more intelligently. It’s a piece of brain candy you’ll enjoy sinking your teeth into.

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: “Mermaid in Chelsea Creek” and the Chelsea Trilogy

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

I wanted to write about this week’s book not because it’s unknown but because it’s a YA title that deserves more reading outside of the genre’s usual audience, and because there are things I want to say about it that I haven’t read elsewhere: things that make it queer, inventive, and otherwise a standout. Its sequel also came out less than two months ago, so now seems like a good time to spread the word about this captivating trilogy-in-progress.

Many of you know of Michelle Tea, prolific San Francisco-based writer, founder of the Radar Reading Series, and queer lit icon. I loved the honesty and manic energy of books like Valencia, and when Tea launched her debut YA fantasy novel, Mermaid in Chelsea Creek, last summer, I fell in love with her again for a whole new set of reasons. If you adore any of Tea’s other books, you’ll find Mermaid in Chelsea Creek to be every bit as transgressive and illuminating. If you ever escaped into the magical realms created by J.K. Rowling or Tamora Pierce, or if you got hooked on what dystopian YA like the Hunger Games had to say about class and privilege, you’ll relish Mermaid‘s intriguing mixture of magic and social realism.

The plot is archetypal: Sophie, a 13-year-old working-class girl, discovers that she is destined to save humanity through her ability to reach inside people’s emotions and heal their pain. (She’s able to recover from the emotional toll of this work by guzzling down salt.) A colorful cast of mentors help her come to terms with her powers and prepare to defeat a villain. Despite having a straight teen protagonist, Mermaid in Chelsea Creek reflects its author’s queer sensibilities. So many female-dominated YA novels feature love triangles, but Sophie’s story is refreshingly free of romantic interests. While her best friend, Ella, is struck by boy fever, stubborn, snarly-haired Sophie is preoccupied with figuring out her nascent abilities and trying to keep her loved ones safe. This first book in the Chelsea trilogy, and the second, Girl at the Bottom of the Sea, offer a convincing character arc of emotional maturation that’s inflected by many relationships but doesn’t rely on any. The novel also stands out for its positive portrayal of a gender-nonconforming character. One of Sophie’s most interesting mentors is a young, masculine-presenting lesbian named Angel. Readers see Angel dealing with microaggressions on a daily basis, but she possesses the toughness and self-regard to shield herself from others; in a neat metaphor, magical shielding is the skill she teaches Sophie. She offers guidance, nurturing, and friendship, and is well fleshed out; in the second book of the trilogy, we see her follow her dream of becoming a youth drug counselor, applying her talent for teaching to something less magical but equally important.

Among the novel’s closest YA sisters are Tamora Pierce’s Circle of Magic books, about four youth who literally work magic through crafts like metalworking and weaving. Tea creates a similar connection between the ordinary and the otherworldly in the first installment of her Chelsea trilogy. Rather than having her characters cast spells by communing with houseplants or the weather, Tea imbues the run-down immigrant town of Chelsea, Massachusetts with improbable magic. It may not be Hogwarts, but in this author’s deft hands, a grubby working-class community becomes as wondrous a setting as any place could be. There’s a mermaid in the trash-filled creek, spouting obscenities and counsel. Sophie meets her while playing the “pass-out game” — an entertainment she partakes in with her friend Ella, which consists of hyperventilating in order to faint and have visions. (It’s clear that there isn’t much to do in Chelsea, unless you know where to find the magic.) Sophie finds friendship in a charismatic flock of talking pigeons, a mentor in a haggard grocery store owner, and a villain at the town dump. The beauty of Michelle Tea’s Chelsea is that the grit and glitter are inextricable.

One can’t write about the magic in Mermaid in Chelsea Creek without mentioning its connections with family and history. It’s noteworthy that much of the magic Sophie encounters draws on her own Polish heritage, from her mermaid advisor Syrena, who normally guards a river in Poland, to the magic techniques she learns from her aunt Hennie, who calls them by their Polish names. “You lose words, you lose power, lose magic,” she explains. Similarly, Angel’s powers come from the curandera tradition she has learned from her mother, and much of her emotional strength seems to stem from their bond. It soon becomes clear that Chelsea’s waves of immigrants have brought their own magical traditions to the town, and that their myths, scoffed at by Sophie’s generation, contain kernels of truth.

Family is a source of power in Tea’s Chelsea, but it’s also a source of struggle. In the novel’s world, good and evil are embodied in Sophie’s relatives in a way that reflects how families relate in the real world. This characterization can be black and white at times, as is common in YA — the kindly aunt is very, very good, and the mean grandmother turns out to be very, very evil. However, this tableau of good and evil is superimposed on more complex dynamics. Sophie envies Angel’s close bond with her implied-to-be-single mother, because her own single mother, Andrea, is harried and neglectful. Sophie’s relationship with Andrea is one of the more heartbreaking aspects of the book, and it becomes more so as backstory is revealed. Sophie’s grandmother’s evil is portrayed through familial acts of abuse, enabling, and emotional manipulation. We come to hate this smug character not because she’s “bad” (a refrain repeated too many times), but for many of the same reasons we hate J.K. Rowling’s Professor Umbridge. Luckily, deep friendships are there to carry Sophie through the hard times.

Mermaid in Chelsea Creek is a splendid example of world-building, and its strength lies in the way it imbues working-class life and realistic relationships with otherworldliness. The sequel, Girl at the Bottom of the Sea, sees Sophie joining the mermaid Syrena underwater and deepening her magical abilities. Sophie’s heart-based magic continues to explore themes of emotional complexity, and Tea again creates an enjoyable world, thoughtfully envisioning what a mermaid civilization would look like (think egg laying and retractable baleen). Less happens in the second book, and without its predecessor’s grounding in everyday struggles, the stakes feel lower. However, it’s still a beautiful read for those who enjoy alternate universes and tales of coming into power. I look forward to finding out what the third installment of the Chelsea trilogy has in store!

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Irena Klepfisz’s “Dreams of an Insomniac”

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

This week’s book is Dreams of an Insomniac: Jewish Feminist Essays, Speeches and Diatribes by Irena Klepfisz. I wouldn’t have discovered this collection if it hadn’t been lying in a free book bin. The gorgeous cover artwork caught my eye: red flowers blooming on a sunset-orange background. It was only by reading the blurb on the back that I learned Klepfisz is a lesbian whose essays address sexuality as one lens of intersectional critique. Her work is important as one of the first texts to explicitly address queer Jewish experience from a woman’s perspective. To this day, Wikipedia’s list of Jewish LGBT writers includes only six women among the 36 names. Irena Klepfisz is not on there, but her work adds a rare and thoughtful Jewish perspective to second-wave feminism, as well as a window into the concerns and activism of Jewish feminist communities between the 70s and the 90s. If you have a cherished copy of Sisterhood is Powerful on your shelf, or a fascination with the ways tragedies are remembered and forgotten, you’ll enjoy this book.

Dreams of an Insomniac was published in 1990, but Klepfisz’s essays were written over two decades, starting in the 1970s. The first two pieces address secular feminist concerns — the choice of being childless, and the oppressive interplay of class and economics in office work — while the other ten essays tackle questions of Jewish identity, memory, politics, and preservation. The collection is fascinating for its rootedness in a certain time, as well as for its moral courage. There is much in these pages to inspire.

The first essay, “Women without Children, Women without Families, Women Alone,” begins with the arresting image of a “shopping-bag lady…[with] discolored skin, the broken blood vessels on her legs, stained purple bruises, barely healed wounds.” Klepfisz writes of her terror of becoming like this woman, and her struggle with the cultural myth that bearing children would grant her “immunity” from poverty and isolation. With great honesty, she dissects her deep-rooted feelings of fear and guilt around her decision to remain childless, cutting through beliefs about motherhood as the sole source of love and security while acknowledging their power. “I have read a great deal about woman as mother,” she writes in her introduction to the essay, “but virtually nothing about woman as non-mother, as if her choice should be taken for granted and her life were not an issue.” A lot more has been written about this topic since, but Klepfisz’s essay stands out for offering a window on an earlier time, as well as for its willingness to examine the darker emotions that accompany “liberation from compulsion.”

Klepfisz likes to write in fragments, and her second essay “The Distances Between Us: Feminism, Consciousness and the Girls at the Office” makes masterful use of this technique, weaving stories of friendships from the author’s intermittent office jobs with economic analyses of the feminist movement and the losses that come with demeaning but necessary jobs: “8 hours a day, 5 days a week, we all lose possibilities, lose self.” She criticizes middle-class feminists for their arrogance toward working-class women — “We act as if we can afford to pick and choose. And we can’t.” She calls for feminist circles to become grounded in an acknowledgment of money and class — “it would be a good idea every once in a while to begin meetings with a ten-minute round robin so that each woman could say how she had spent the day.” This is a long and intricate essay that merits rereading for nuance. No matter what your circumstances, you’ll see aspects of your life reflected in it.

The rest of the collection will be of particular interest to those connected to the Jewish community. For those who are not, it offers thought-provoking perspectives on identity, memory, and how to work toward change. Especially interesting is Klepfisz’s take on lesbians and the Jewish community, which excluded them when she began writing the collection and later became more welcoming. She notes the many parallels between queer and Jewish experience, and concludes that the often-excluded queer community has a lot to offer the Jewish community in addressing its own challenges: “These are serious issues which require imagination and creativity. Lesbians and gays have these to offer and perhaps even more.”

A Holocaust survivor who escaped from Poland to America as a teenager, Klepfisz includes a powerful diary about revisiting Poland and witnessing the erosion of Jewish presence and memory there. This disappearance is made physical by “the unchecked sinking of gravestones into the ground,” the presence of crosses and absence of Jewish memorials at Treblinka, and the assimilation of family friends’ children into secular Polish culture. She critiques the transformation of the Holocaust into symbols and narratives, to the point that the public can get “turned off by the Holocaust.” Following this experience, her writing seems to become more committed to the preservation of secular Jewish culture. She writes of taking action against Israel’s military occupation of Palestine (not so different, she argues, from the violence Jews have experienced) while maintaining pride in her Jewish identity, preserving Yiddish language and literature, and seeking out female voices to add to the Jewish conversation. Her work speaks to the complexity and necessity of taking a stand. Let’s be real, these essays urge us. Let’s roll up our sleeves and do the work that needs to be done.

Hidden Gems of Queer Lit: Chrystos and ‘In Her I Am’

Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

Chrystos is one of those poets who qualifies as a “hidden gem” herself. A Menominee rights activist who identifies as Two-Spirit, her writing offers depictions of the harms of colonialism, the struggles of solidarity, and the earthy joys of lesbian love affairs. Despite being a prolific writer, well-known and well-traveled in the 1990s, her books have gone out of print. Despite being one of the most beloved and prolific queer Native American writers, I seldom hear her work discussed in literary circles. That’s a shame, as her poetry is trailblazing.

While her other collections tackle a wide range of topics, In Her I Am (1993) offers an unflinching and deeply sensual look at queer desire. In her introduction, she describes the lesbian culture that welcomed her in the 1960s as a place of gender performance and active lust, and admits that “The rejection of this very sexual culture by feminist Lesbians has marred my relationship with Women’s Liberation from the beginning.” Taking the subject of sex seriously in a way that isn’t often done, she goes on to write a sort of poetic playbook of the power plays, freedoms, and joys of one woman’s erotic experiences. If you appreciate Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s political awareness, Michelle Tea’s frank confessions, or Sappho’s languorous sensuality, you’ll find something to love in this book as well. It’s one of the most remarkably intelligent sexy reads out there, showing desire, even in its most “deviant” forms, to be both honest and dignified.

This is a book you’ll probably want to read in your room with the door closed. Natural beauty mingles with human beauty in lush, omnipresent metaphors: “She speaks burgundy birds,” or “my toes skim stars.” This is poetry of wild trysts in the car and on the stairs, wet mouths, dildos, and “flames in my fingers,” where even making blackberry jam becomes an act of seduction. Often, the sex act becomes a way for the narrator to reclaim and rewrite history: “We’re in the grass of prairies our grandmothers rode…Flaming ride us past our rapes our pain / past years when we stumbled lost.” Such gestures are remarkable in Chrystos’ writing, known for its unwillingness to erase brutal realities and its careful examination of the wounds of colonialism. Her remarkable first poetry collection, Not Vanishing, shouts in the face of the “vanishing Indian” myth. Chrystos is not one to deny truths or plaster on band-aids; if any healing force is attributed to love or desire, that’s because it’s there.

Chrystos is a sharp observer of power dynamics. Her introduction and conclusion are unpunctuated prose poems that presage Patrick Stewart, an architect from the Nisga’a First Nation, who wrote his dissertation without punctuation as a form of resistance against colonialism and “the blind acceptance of English language conventions in academia.” They tease out connections between sexuality, colonialism, and ethics and lay out the “matrix” the poet has set herself for principled non-monogamy. Chrystos’ refusal of myths of romance and sexual ownership and her commitment to these ethics, learned from experience before The Ethical Slut was a thing, intrigues. Her poems depict a delightful rainbow of lovers, from dreamy, bouquet-bearing Lakota women to tough butches “who pack.” Her warning in giving thanks to them at the end of the book, “no, you can’t have their #s”, is well-warranted! She’s equally apt at uncovering the interplays of power and pain present in lesbian communities. “Top Sadist in Town,” one of the collection’s longest and most rewarding poems, depicts a seduction gone wrong with an “s/m” practitioner terrified by the writer’s unwillingness to “pretend for Her sake to be frightened.” Chrystos writes equally well of her own tendency to disguise resolve with vulnerability: “tie me to my bed with silk so I can’t get away / since I don’t want / to anyway.”

This collection intelligently portrays the varied forms of joy and pain, entrapment and freedom that sexuality can give birth to. It has its funny moments, too, like the tongue-in-cheek personal ad “Dream Lesbian Lover,” calling for a woman who “rubs my feet for hours… & thrives on 5 hours sleep a night,” or Chrystos’ mocking of a lover’s cynicism about romance: “Hey I thought I saw you riding by on a white horse / but you say you don’t believe in that goo… / Next time you ride by I’ll be saddled / ready to go.” Her thoughts on BDSM are complicated, and kinky readers may not always find themselves on the same page. Nonetheless, there’s much delight in these pages. Come for the thighs and flowers, and leave with a greater understanding of the complex healing art of pleasure.