Quiz: Which Queer Book Should You Read To Close Out AAPI Month?

I’ve gathered suggestions from the Autostraddle team and consulted my personal reading list to offer you a very unique reading recommendation! Please enjoy a captivating queer read by an AAPI author as we move into the season of leisurely reading by the pool and generally being gay.

Editor’s Notes: On AAPI Heritage Month 2021

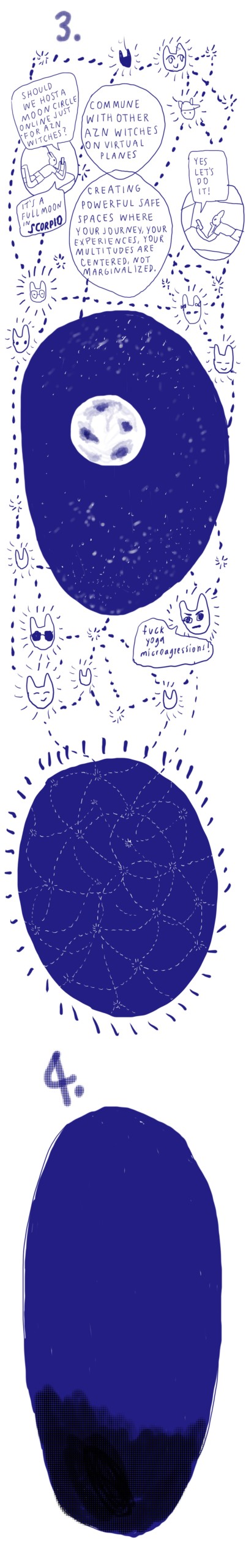

An inside look, just for A+ members, from Autostraddle’s editors on the process, struggles, and surprises of working on what you’re reading on the site. We learn so much from this work before it ever even makes it to your eyes; now you can, too!

The last time I did anything remotely like this was fifteen years ago, when I edited my high school’s literary journal. And then I graduated, set my sights on other pursuits and stopped writing.

But, now, I’ve found my way back.

Fifteen years ago, I had deeply disconnected myself from being Asian. By that point, I had long stopped watching Bollywood movies, hated eating Indian food and never told anyone I was obsessed with anime. The notion that I might actually be queer was beyond anything I could possibly imagine. So, I can’t help but smile, albeit a little sadly, that what’s pulled me back into this world of writing and editing is my desire to make sure that the stories of queer and trans Asians and Pacific Islanders are told in ways that feel true to us. It took me fifteen years to bring all these threads together, but I suppose — at least, I made it?

I haven’t been on the queer part of my journey for very long, but when my relationship ended two years ago, the first thing I did was look for queer Asian stories. I wanted to know that I wasn’t alone, that the things that felt impossible to me were things others could relate to as well. I found some of what I was looking for, but what quickly became clear was the scarcity of API perspectives in queer and trans discourse. API identity is, for better or for worse, a massive umbrella covering large swathes of the world, and yet the breadth of it barely registers in a cursory search for queer/trans Asian/Pacific Islander content.

When I started thinking about the theme for this year’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, I was reminded of words Karen Lee had shared with me in an interview about the pandemic last year. Karen is one of the co-chairs of Q-Wave, a NYC-based community organization for queer Asians who identify as women, nonbinary and/or trans. Reflecting on what it means to be queer and API she said:

“Often times, you think of queerness as a white thing, and then when you think of Asian-ness you don’t see any room for queerness in that.”

Her words resonated deeply with me, and I’ve held that thought for well over a year now. As I watched anti-Asian violence come to the forefront in the wake of the pandemic and saw Asian communities contend with their relationship to policing after last summer’s protests, I witnessed both the vulnerability and the strength of being queer/trans and Asian/Pacific Islander. Some of the most marginalized members of the API community, facing the dual or triple threats of racism, homophobia and transphobia, were also the ones trying to move their communities to find new ways to protect themselves from violence without relying on increased law enforcement. What does it mean to exist in that liminal space, constantly pushed to the margins on both sides, told that you are neither Asian enough nor queer enough, and yet to be the one propelling both of these communities forward?

As we discussed the theme for this year’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, Autostraddle’s trans subject editor and co-editor for the AAPI Heritage Month Series, Xoài Pham gently nudged me to move past mere reconciliation. She said:

“We are always reconciling our identities as queer Asians. What happens when we move beyond that and begin taking up space as our whole selves?”

And I realized, this was Karen’s point as well. That to exist as a queer/trans Asian/Pacific Islander means to put your stakes in the ground and to say, “I am all of these identities, and I exist, so therefore these identities are me. They must be.”

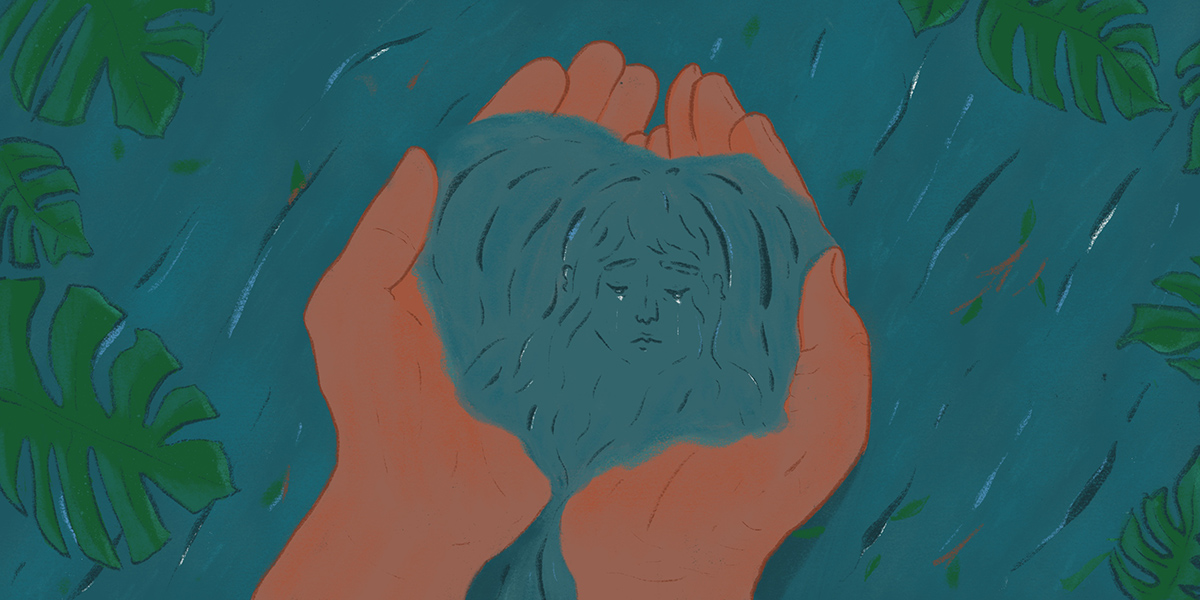

From start to finish, this year’s AAPI Heritage Month has been about queer/trans Asian/Pacific Islanders laying their claims to all of themselves. Over the course of the last month, over a dozen queer and trans writers and artists from all over the API diaspora have shared what it means to them to hold all their identities in all the pain, pleasure and power that entails.

It’s truly been an honor to have been trusted with these stories, and the stories of dozens upon dozens of others who pitched to be part of the series as well. There is so much richness and so much nuance and so much depth to being queer/trans and Asian/Pacific Islander. In this year’s AAPI Heritage Month, we’ve been able to hold space for a small sliver of it in the hopes that through sharing this work, queer/trans Asian/Pacific Islanders from all over the world feel a little less alone in taking up their own space, as well.

The Right to Breathe

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

![]()

I’m struggling. More so than usual. What over a year of grieving through a pandemic has given me: the courage to let go of the stories I told myself as coping mechanisms.

I am not okay. Most of my life, I thought I would be okay if I got pretty enough, successful enough, had enough friends. If I looked like I had myself put together, maybe it’d be real somehow. But I’m not okay. I am scared. And many days, I think happiness is impossible.

![]()

The average person, at rest, breathes 12 to 16 times a minute.

![]()

A few weeks ago, a Vietnamese man in Indiana offered two men a ride home. He was then killed and dismembered in his own car.

“Did you hear what happened to Shane Nguyễn, Ba?” I ask my dad. “Don’t talk to anybody. Don’t let anyone near your car. Don’t go outside alone.” He’s the type to be generous to strangers. There are many people who want to see my father dead more than anything else. I tell him I’ll be ordering self-defense keychains for the family.

![]()

Babies cry when they’re born in order to expand their lungs and eliminate fluid blocking their airways. They cry to breathe. “Your baby will cry as long as he needs to in order to start breathing normally,” pediatrician Ana Machado told Romper.

I cry at least once a day, sometimes wailing. I think of the moment I was born, how I must not have cared at all how loud I screamed. I needed to breathe. I needed everyone to know I was here. At times, I wash my face before bed and the sight of my face, so exposed like I’m seeing myself for the first time, brings me to tears.

![]()

It’s been six months since I decided to download a dating app. After being in a relationship for two years, I forgot how bleak romance is for trans women. I am distorted, bent into different shapes by the whims and fantasies of men. Some men find trans women repulsive. Some just want to know if I have a dick. Some want to experiment to see if they’d like what they see. I am a sex toy expected to have endless customizations. And all I want is someone to hold me. All I want is to know what someone out there will hold me. I admit to myself, wholeheartedly for the first time, that I want a storybook romance.

At the moment, there are over 100 bills restricting access to public life and healthcare for trans youth in U.S. state legislatures. They don’t even want us to have healthcare, let alone experience love.

![]()

I walk home, my thumb on the trigger of the pepper spray. I stroll past a family playing music on the sidewalk, the children’s giggles making the air lighter. Then, two bikers speed along my left, the rush of air from their bodies brushing across my cheek.

I turn the dark corner, and here is my light-strewn block. My relief ends quickly when a man also turns the corner. I look back at him and he says, “Hey, baby.” My breath quickens.

I start to walk a little faster. Sarah Everard‘s name crosses my mind. In March, she was walking home from a friend’s house in London. She was last seen on a main road at 9:30pm before she was reported missing and later found dead. I pull out my phone: 9:42pm.

His voice feels close, “You’re so beautiful. Come talk to me.” He says other things I can’t make out. I pretend to be observing something to my left and try to catch how far he is from me with my peripheral vision. I’m only about 20 feet away from my building. I observe how far a bystander might be. There’s someone on the next block who’d hear me if I screamed.

“Let me get your number, beautiful,” he continues, even though I have yet to say a word in response.

I turn into the entryway of my building and sprint, scrambling to get the key fob to scan. I’m frantic now, I can hear my heavy breathing. I look back to make sure he hasn’t caught up. The door buzzes and I crack it open just enough to slip inside quickly, so it can close and lock.

![]()

It’s been shown in studies that marine mammals, like bottlenose dolphins and pilot whales, synchronize breathing to reduce tension and stress. The synchronicity increases in highly social situations where many whales are present.

In humans, strong bonds produce what scientists call “interpersonal synchronicity.” Couples sitting together would unconsciously align their breathing rates and heartbeats. Dr. Pavel Goldstein’s study with the University of Colorado, Boulder found that when one partner experiences pain, it interrupts the synchronicity. But when the couple is allowed to hold hands, physical touch reduces the pain and allows them again to fall into sync.

![]()

“Aloha is not just a greeting,” my sister explains. “It means we’re exchanging breath, or what we call hā. Our breaths are connected.”

![]()

Derek Chauvin was a rare case: police officers are rarely convicted of the murders they commit. In his last moments, George Floyd said “I can’t breathe” more than 20 times. The final words he uttered were: “They’ll kill me.”

Mhelody Bruno was a Filipina trans woman who died of what the court called “erotic asphyxiation” in 2019. Her boyfriend at the time, a corporal in the Royal Australian Air Force, pleaded guilty to killing her by choking.

Five years earlier, in October of 2014, another Filipina trans woman named Jennifer Laude was killed by asphyxiation at the hands of a U.S. Marine. She was found slumped lifeless over a toilet.

Three months prior, in July of 2014, Eric Garner‘s last words, too, were “I can’t breathe.” Like George Floyd, Eric Garner was a Black father. The police officer who killed him with a chokehold, Daniel Pantaleo, was not indicted.

![]()

In November of 2020, my dad caught COVID-19. Luckily, I was home for the holidays. His condition worsened quickly. He spent all day in his bed, reading and eating the little bit that he could. We delivered food to his door and he’d hobble over to retrieve it. We started placing the tray of food on a high chair when it was clear he couldn’t bend down.

I bought a pulse oximeter to measure his blood oxygen levels. “Ba, can you breathe?” I asked him every morning, afternoon, and evening.

He didn’t have the air to speak. So he started texting me. “Oxygen level up and down today,” he’d write. My childhood nebulizer, a hulking machine that felt like a hospital’s version of hookah, was placed in his room. He spent 15 minutes inhaling vaporized medicine every night before bed. I remembered all the times he was the one preparing the medication for me, when my asthma was a daily pain.

The roles were reversed.

I wrote him letters every day. It felt urgent to tell him everything I wanted him to hear: I love you. I’m proud of you. I want you to forgive yourself.

There’s a Little India in South Africa

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

![]()

Five years ago in Colaba, Mumbai, my jaw dropped as I surveyed the artwork in a Maharashtra gallery depicting Hindu deities with dark skin. In a state of bewilderment, I complained, “Back home in South Africa, in all the years that I snuck into my grandparents’ prayer room, I’d never seen anything like this. They were always depicted as light skinned or blue!” A Mumbai based artist herself, my friend Priyanka nodded her head and explained the whitewashing and colorism in Indian art history and society. It didn’t surprise me, given the frequency with which I had personally experienced this from Indian family members growing up.

“Tell me something I don’t know!” I said, and she explained how Raja Ravi Varma’s artwork circulated India and the Indian diasporas. Born in 1848, Varma gained acclaim and criticism for his work depicting his interpretations of Hindu mythology into the European realist historicist painting style. Amongst his extensive collection, works like Shri Rama Vanquishing the Sea offered viewers an opportunity to put an image to moments in mythology as Varma interpreted the stories of Hindu deities and characters in the epics and Puranas. In 1894, he set up a lithographic press, allowing his work to be reproduced en masse at a low rate. The innovations in technology created an affordability for ordinary people and his work began to circulate homes of people on every continent. While some write him off as a “calendar artist,” his work has had a significant impact on Indian popular art, influencing Indian religious art for generations after his death.

Raja Ravi Varma, Saraswati

“So white Krishna is like white Jesus, then?” I asked. She laughed, explaining that although Varma’s work was far more contemporary than the depictions we’ve come to know in Christianity, it could lead to the same type of white-washed depictions that have no grounding in scripture.

We left the gallery and walked around Apollo Bandar until we reached the gateway of India, which arches over the Indian Ocean, creating what feels like a portal. Inscriptions on the wall read, “Erected to commemorate the landing in India of their Imperial Majesties King George V and Queen Mary on the Second of December MCMXI.” I sighed, heavy-hearted, wondering what secrets those waters held.

![]()

On the Southernmost tip of Africa, the East Coast is met by the Indian Ocean. Salty and humid winds pass through the hills of greenery, which seem luscious and never ending. Whenever I land in Durban, South Africa, there’s no feeling as sweet as home nor a drive so bitter, as we pass through sugarcane plantations for miles on end. Outside of India, Durban has the largest population of Indians in the world. The population is heterogeneous, with each family line arriving at different times and under different circumstances, ranging from people who were enslaved during the Dutch colonial era, to “indentured laborers” who worked on the sugarcane plantations, to “free Indians” who immigrated at their own expense.

Apartheid-era laws had segregated the population into racially homogeneous areas. Due to the notorious Group Areas Act, Indian communities quickly formed their own worlds within South Africa, almost completely separated from the experiences of other populations and cultures within the country. To create further division amongst people of color, the Apartheid government insidiously established a racial hierarchy which placed black and indigenous people at the bottom of the rank, enforcing superiority complexes and anti-black stereotypes. To suffocate less under the Apartheid regime, one had to try their best to gain a closer proximity to whiteness through assimilation.

The caste system within Indian culture adds fuel to the fire of white assimilation in South Africa. While the caste system is specifically related to a hierarchical system of social organization within Indian culture, colorism becomes intertwined as privilege and esteem is often assigned to lighter skinned Indians. Although skin color diversity exists within each caste, historical biases towards dark skinned people remains prevalent to this day.

South African Indians have also creolized the rhetoric around the subcultures within Indian culture. People are identified amongst the group through their surnames and family histories to name a few factors. For instance, Tamil people became known as Porridge O’s (Porridge people) for their involvement in prayers known as Marie Amman Poojay. While the experiences and history of Tamil people in South Africa is not homogeneous, colorism and caste bias arise within the Indian community through anti-dark skinned slurs which are used to stereotype and demean Tamil people by associating them with the embodiment of evil from the Ramayana. And, While Roti-O’s (Roti people) are broadly defined as Hindu people, there is a distinction between religion, culture and caste as Hindu Tamil people are not considered as a part of the group. Roti-O’s are often stereotyped as lighter skinned, more affluent and while the group is not homogeneous, there is a potential for a more privileged historical introduction to South Africa due to their higher social status within the caste system in India.

![]()

When I was born, my grandmother tried to squeeze the blackness out of my nose. She was horrified at the size and shapes of my features, scanning my infant body to find evidence of “non-Indianness” as quickly as possible, while I was still malleable. My mother walked into the room one day in protest, to which my grandmother responded, “There’s no bridgebone! You must pinch it like this everyday while the baby is still small, and it will form!” Astounded yet unsurprised, my mother pulled me away and yelled, “You’re suffocating the child!”

As the years went by, I slowly grew into my skin with a sense of pride. At school, kids bullied me for my features. “Hey Phuthu lips.” (A staple in black communities in South Africa, Phuthu is a dish made from ground maize meal.) When I told my mother about my nickname at school, she laughed, “Tell them it’s called Hollywood lips,” and although I never did, I watched closely as she affirmed everything she was criticized for, wearing it like a crown.

My high school had an Indian majority population, with students from different castes and historical backgrounds. As people aged and entered the dating scene, an underground market for skin whitening creams emerged at school. The “boys” bleached their hair blonde and secretly sold whitening creams out of their backpacks, in an attempt to win the attention of “girls,” with their Jonas Brothers inspired aesthetics.

While I witnessed high school cisheteronormativity and colorism dominate the scene, I was met with an array of people across the color and gender spectrums who stood proudly in themselves amidst the noise. From owning their sexualities in a homophobic climate, to acknowledging the beauty in being dark skinned, the process wasn’t neat, with negative self talk recurring in the process of affirmation. Regardless of the tumultuous nature of the cycle between affirmation and negative self-talk, it’s impressive to imagine the generational cycles that high school children were beginning to break with their shifting perceptions of self.

Deep within queer confusion and grey asexuality, I found myself in pockets of LGBTQ+ community, avoiding the dating scene and the school culture altogether. As I recluded into myself, I connected with a Hindu non-binary femme, who told me of her acceptance within the temples of Durban. Growing up, I’d quiver to imagine Muslims or Hindus in my family responding positively towards my transness. She explained, “I’m not just accepted, I’m celebrated. I’m in charge of all of the food preparation, and I’m part of the rituals for certain prayers like Kavadi.” She explained her process of praying and fasting as she prepared to embody the goddess Kali and carry chariots during the festival.

I began to notice the gaps between the transantagonism I experienced in daily life and scripture as I learned about the existence of trans people within Indian and African societies throughout time. There is a pattern in the way colonization has distanced people from affirming the diversity within their own cultures. On one hand, colonial influence had led to a progressive cultural whitewashing, and on the other hand, it buried the layers of gender diversity that was accepted in ancient culture and religion.

Transness, though often stereotyped as a Western innovation, has existed on the African and Asian continents for as long as humans existed. The more I spoke about LGBTQ+ elders amongst friends and studied the history through articles and photographic archives, I saw the way my ancestors looked down on me with love, instead of shame. In a similar way that my jaw dropped when witnessing dark skinned deities represented in Mumbai, I find myself enamored at the richness in gender and sexual diversity, which has been buried under years of colonial influence across cultures.

![]()

The streets of Coloba, Mumbai are lined with Banyan trees that hold offerings in their trunks. Garlands of flowers are hung in ceremony as sages and ordinary people pass them by. Priyanka had said that it’s a holy tree that sages sit beneath in prayer. In Durban, there is a Banyan tree in my mother’s backyard. It had been there for years before we moved there, and in all the time that passed us by, we never guessed it’s origin until Priyanka had explained its significance in India. Somewhere down the line, someone from India tried to carry a piece of home with them to South Africa for familiarity and possibly, a place to pray under.

The Birth and Death of a Name

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

I.

This is the story of the birth and death of my name, which means that it is a story about transition, which means that it is necessarily a story about the border between two places and the force with which one rends it. Which means that if you must trace this story to the very beginning, back across three languages, two continents, and countless bodies of water, you will find that this is the story of a boat.

The first boat left a hundred and ten years ago. It left alone, and at night, from a few boards nailed into the dirt with the audacity to call itself a port. Those who stepped on it would never return. All the songs that remain from that time are lamentations. The destination of the boat was not west, but south, toward the equator, where seasons were rumored to have disappeared and even the rain fell warm onto the ground.

If you were the Dutch men in the port awaiting the boat, here is how you would describe what you saw: a small sea of bobbing black heads within a larger sea. Shallow mud in shallow mud. Fair skin, cheekbones that melted into their faces, taut little mouths that crowed even from afar. They were different from the natives of the land you were colonizing, and so they posed a different kind of threat. You had plans for them.

The boat swelled with men and then spat them onto the land. These men tumbled out, dragging their wives off the boat by their wrists and into the land where the ground steamed with heat and seeds sprouted from it unbidden.

They birthed their children and tied red string around their wrists. They did their best to fill their mouths with the language they brought with them. They built churches. They built schools. It all worked: though they never returned home, the language persisted. Among the children of these people were my grandparents.

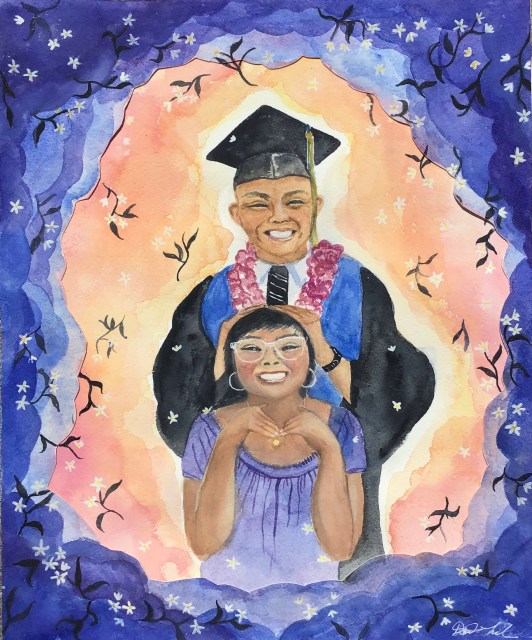

Illustration by Joyce Chau

I call it the first boat, but this boat was not first in any meaningful sense of the word. It was not the Mayflower, though the people came for the same reasons. It was small and cramped and almost certainly very smelly. Shit wedged its way between the floorboards. Phlegm dried into the railings. The ledger is long gone. So there are no records of this story I can show you, no proof it occurred.

Nevertheless, my grandfather is here, and I am here, and this is what he told me when I asked. And so, at least in this story, this is how it happened. Whether you believe it or not is up to you.

![]()

Indonesia was dark and warm. The streets were lined with palm trees and cracked dirt. You could buy fruit that sliced into stars, build yourself a thatched room with a dirt floor, find a body of water anywhere you looked. Nevertheless, Indonesia was not a paradise for the Chinese. Tiffany Tsao, a Chinese-Indonesian scholar, translator and writer, notes that common perceptions of the Chinese in Indonesia were as “money-minded, shrewd, and hoarders of wealth.”

Though people of Chinese descent have migrated to the 17,000 islands that comprise what we now call Indonesia since the thirteenth century, systemic national discrimination only began in earnest with Dutch colonization of a place they named the Dutch East Indies. It was an undignified name for a country, derived from the capitalist and colonial enterprise that was the Dutch East India Company. Like many other colonized places, it could not even name itself.

Tsao notes that when the Chinese immigrated during the early twentieth century, the “Dutch administrators segregated Chinese areas from the native population” and deployed “Chinese traders as merchant middlemen” to reify the reputation that they’d invented. This is how the Chinese came to be perceived as a wealthy, penurious, grasping people, a belief that still continues in Indonesia to this day, long after the Dutch have left.

The Chinese found ways to keep their dignity, as people always have, and perhaps even more in more dire circumstances. One of these was through their names. In China, neither women nor men changed their names, even upon marriage; this tradition continued in Indonesia. So though my grandparents were born in Jakarta, they were given Chinese names, and each could well expect to keep their name for the rest of their lives.

Amidst the loathing, the discrimination, the humiliation and ignominy of having a Chinese face, a name was that inviolate thing that would reverse the motion of the boat, slow the inexorable crush of history. Nothing — not migration, adulthood, family, privation, or even death — could take it away from you. In an environment with so little record-keeping to tie one to their past, the name was a way to remember.

In the parts of China I came from, all the members of a family’s generation would share the same first syllable of their given name. So with little else than a name and patience, you could approximate a person’s age, reconstruct what village and province they belonged to. More than being the contents of an archive, the name was a small, complete archive unto itself.

![]()

This changed in 1965, when Suharto, the general of the Indonesian army, wrested power over the Indonesian government in a military coup. Scholarly retrospectives of his 32-year reign would call him the most corrupt political leader in modern history, as well as the orchestrator of wholesale cultural genocide of Chinese-Indonesians. Suharto did not delay in fashioning such a reputation: in 1966, the Indonesian government passed Cabinet Presidium Decision 127, a law that commanded all Indonesian citizens of Chinese descent to change their names to Indonesian ones.

Theoretically, there was no consequence to disobeying this law. Yet the staggering majority of people still changed their names, that thing that had once been sacrosanct. There are many forms of consequence that do not require penal intervention, and to not change one’s name came with a steep social price that could lose a person their job, get them rejected from university, turn them into a social pariah.

The stakes were too high for most to keep their names. There was, however, some form of preservation, however meager. The Chinese snuck their old names into their new surnames, often by concatenating the old surname with an Indonesian-sounding prefix or suffix. The name “Wong” might become “Widjaja;” “Lim” could turn into “Halim.” In this way, people tried to remember themselves, even if through a poor rendition of what they once had. The name itself would become that marker of a distinct Chinese-Indonesian identity, separate from both a native Indonesian and a mainland Chinese one.

![]()

At the ages of 26 and 30, shortly after the birth of their first child, both of my grandparents sent in their name change papers. My grandfather tucked his old surname into the first syllable of his new first name. Other than that, however, every other syllable was new. It sounded strange in his mouth. It still does.

Sometimes I wake up in a panic, hands clawing at my chest. I think of how it must have been to be called something new that far into your life; how a foreign name was precisely what made you not a foreigner anymore.

Sometimes I wake up in a panic, hands clawing at my chest. I think of how it must have been to be called something new that far into your life; how a foreign name was precisely what made you not a foreigner anymore. One night, I called my grandfather to ask him if he would have given my mother a Chinese name if the 1966 law were not passed. He laughed when I asked this, as if it were obvious.

In fact, he had prepared for her a Chinese name, when my mother was still gathering herself in her mother’s womb. He did not consult the elders in the village as to what the generational syllable of her given name would be. That particular ability of a name to tie a person to a set of similar people was already gone, the process of assimilation well underway even without Suharto’s intervention. Nevertheless, it was a Chinese name, and perhaps even a good one.

But my mother was born in 1966, the year that Cabinet Presidium Decision 127 was passed. So when it came time to write her name down for the birth certificate, they followed the government’s orders. They made something else up. My mother was the first person in her family to have an Indonesian name. The Chinese name lives nowhere now. It exists on no document, on the heading of no school paper, on no birth or marriage certificate. My own mother does not know it.

I asked my grandfather if he still remembered what it was. He told me the name, and I wrote it down. He said it was the first time that anyone had ever done so.

II.

The word “slur” comes from the Middle English “sloor,” meaning “thin or fluid mud.” The mud, and the dirtiness that mud entails, led to the word’s modern, prevailing definition of “an insult or slight.” And the fluid nature of the mud, conferred that other definition: that of a set of notes or words to be played legato, without the cruel interjection of silence. Drunkards slur; so do violins. A slur is a crucial element of music, and not just any music, but the most beautiful kind, where notes gather together to form the raw material of hymns and lullabies.

It is a difficult form to perfect, the slur. Much constrains it. It demands brevity: one, two syllables at most. You must be able to spit it, also whisper it under your breath. It must stand as a complete sentence unto itself.

In the United States, there are all sorts of slurs for East Asian people. Few stretch the imagination; few have that fulminant energy that really reveals the dual nature of the word, explodes an insult into song. But still: the English slur has always demanded at least a minimal form of creativity.

Not so much in Indonesia. Over there, it’s sufficient to use the name of the thing itself. Specifically: Cina, spelled just like that, with a hard “ch”, untempered and uncompressed by the “ai” the way people say it in English. “Chee-nah”: the inflection is all it takes to move it from innocuous descriptor to a mouthful of splinters. It is propulsive — say it enough times, and it will send you back to where you came from. Sometimes, it will even send you forward.

After the 1966 Decision, an identifiably Chinese name would itself become a slur. To keep such a name immediately outed a person not only as ethnically Chinese, but also a law-breaker, a person actively opposed to assimilation and the new government under Suharto. It was only right that as the name itself was the evidence of the crime, the name would become the thing spat at its owner.

![]()

With all that regulation, there wasn’t much room left for dignity. Our names were gone. We were still targets for extortion. Our schools were shuttered, our churches razed. Dignity was not given to those who were vilified by their colonizers, loathed by the colonized, respected by no one. Dignity could not be traded, sold, hoarded, packed away in vaults. No, it was no longer economically viable to traffic in dignity.

We trafficked in vulgarity. Hands shoved into pockets, skin that withered in the sun, mouths in a constant state of rudeness. We went into business, exactly what they had accused us of doing. The myth was building itself.

First, the Dutch had helped. Now, Suharto’s government was helping. Tiffany Tsao notes that during this period, the Indonesian dictator “cherry-picked a small handful of ethnic Chinese businessmen to build the nation’s economy, utilizing their capital, networks, and expertise.” In return for the prosperity of a few, Suharto used them as examples to prove malignant stereotypes of Chinese people.

![]()

My father tells me what people said to him when he was growing up in Jakarta. Or rather, he tells me what he would have said back to them, if he had the nerve. Instead he only ever says it to me. When he says it he looks so far away.

You call me Cina, Cina, tapi saya yang punya uang; kamu enga punya uang, he gloats.1 He does not say it in Chinese. No one in my family speaks Chinese anymore.

There is both glee and intense bitterness in his voice. It almost emits a smell. His shirt is full of holes where the sleeve meets the armpit. He has worn this shirt thousands of times. I was the one who benefited from it. He used that money on me.

I find him both very desperate and very brave. But I wish he would behave better.

![]()

Here is how the Dutch would have written his story.

There is a Chinese man. And Chinese men crave money. This one is no exception.

He has no money. All he does is think about money and how far away it can take him. He applies to the university. There is a quota for people like him, but he is bright and shrewd, all the weakness wrenched and natural-selected out of him. So he makes the quota. He studies; he studies so much he stops having dreams. He graduates. He becomes a businessman. Of course he becomes a businessman.

Whenever he visits us in America, he buys used textbooks online, back when books were one of the few things you could buy online. He tapes them back up in tattered cardboard boxes, wraps the whole box in tape, leaves not a single inch of cardboard exposed. He ferries them back to Indonesia, sells each book, piece by piece. He hoards the money. He devises a long, patient, multigenerational plan to protect his children from ever being called <em>Cina</em> again.

![]()

We permanently moved to America shortly after I was born, sixteen months before the 1998 riots that marked the end of Suharto’s regime. Or, rather, my mother and I moved. My father stayed in Indonesia. He had a business to run.

But he gave me a white name to take with me. It was a prosaic name, a common name, a cautious name, and he gave me no other one. The sort of timeless name listed on the top 200 girls names in the United States for a hundred consecutive years. The sort of name that could be worn like armor.

It worked. I learned the reason for the name’s enduring popularity firsthand; it was practically unweaponizable. I received no slurs. The smell of my Asian lunch offended no one. In America, my parents had found one of those sufficiently affluent neighborhoods for me to grow up in, full of enough well-to-do immigrants, that rendered such concerns as overt racism, at least toward Asian-Americans, obsolete. Even in those early days, we were poor but not vulnerable. And then, time passed, and we weren’t poor anymore.

![]()

I have never been called a chink until I moved into a city well into my twenties. I have only been spat on once. I frequently walk alone at night. To say I fear for my safety would be disingenuous.

I have a young, able body that answers to me, and I know the terms of this game. I know not to open my mouth and reveal the ugly surprise of my voice. And so, for the most part, when I follow these rules I do not feel fear.

III.

Life, however, always finds a way to introduce new kinds of shame. The first was the shame of a girl. The second was the shame of a disobedient girl, the kind who wielded a razor on her hair both too little and too much. The last was the shame of a girl who stopped being a girl at all.

![]()

I don’t want to justify myself. But my mom laughs whenever she sees me. She tells her friends her daughter looks like a boy and every time it feels like rubbing sand into my skin, turning myself into liquid by the sheer force of it. But I stay quiet. I keep cutting my hair. Sometimes I think of doing more.

![]()

After I had meditated on the idea of my transness for a sufficiently long time, I thought that I should change my name. It felt like the trans thing to do. For many trans people, it is the right thing to do. These are the people for whom transition feels like “coming home.” For these people, changing a name can prevent a person from getting misgendered. It can assure a person’s safety. I’ve been told that it feels a lot like walking from shade into a hot square of light.

But what does it mean to change your name when your home does not want you? And what does it mean to change your name when you know nothing of your home? To change a name also feels so violent, hurts so much. It feels like not remembering, when all that I want to do is remember.

To change a name in the service of one’s transness is that act of transforming one’s birth name into a slur. The “birth name” becomes a “dead name”, and to call a person by such a name is unconscionable. It can destroy a relationship. It can end a family. It could end my family. And, however much white people say it, it is not true that I owe my family nothing.

So is this what I want — to end a family?

![]()

I don’t consider myself to be transitioning anymore. I’ve stopped trying to go home; I get things all mixed up. It physically tires me to read Indonesian. I use a translator whenever I have to read anything with a word longer than two finger-spans length.

Cina, jorok, berisik: these are the sorts of small words I know; I use them to become someone else. I was not taught them, but I heard them anyway. I know how to be furious in this language. I know how to call a man an idiot four different ways, and the exact degree of nuance to each of those words. I know the words for foam and dirt and spit and water. Also pain. It is so easy to be angry in this language with the few words I remember.

I have a friend, a trans man. A trans elder, really, one of those people who transitioned long before any of our modern day trans influencers came into being. When he transitioned, he sloughed off the name that his parents gave him. But not the first one; the one they gave him when they moved from China to the United States.

He changed his name back, or perhaps forward, to his birth name. For him, transitioning was not migration. It was a return from exile.

He changed his name back, or perhaps forward, to his birth name. For him, transitioning was not migration. It was a return from exile.

I am jealous of him. I wish that I had an Indonesian name, or a Chinese name, or a true birth name, and not this white thing, all sanded edges, all watered-down mud. I want a name that burns the back of a throat. I want to dismember a man using only my blade of a name. I wish I had something more true to come home to.

![]()

The story of the birth and death of my name ends here.

In it, I have a name that has sewn me to a history of migration — one of those ageless tales of power and violation. It is not a particularly superlative story, but it is mine.

All of the family photos are gone. My grandfather threw them away this year when my grandparents moved in with their daughter, my aunt, to live the quiet years of their life. It was too late to stop him, but in the end it didn’t matter. He did not weep at their absence. He did not mourn those incinerated paper faces. He forgot about them. His memory was loosening its grip. And the documents — well, those were long gone, lost to time and the wastebasket. There was so much to remember, and so little to hold onto.

So here it is: the remembering, the last archive of what I have left. It’s small enough to fit in your mouth. Hold it there — this name that contains an entire girlhood, and my grandmother’s disappeared name, and the last name my dead violin teacher would know me by, which makes me cry every time I think of it, and her. A name that holds the whiteness thrust upon me, and all the hope of my family — to move us forward, also to stay the same.

My first name, my given name, my birth name, that small poor shriveled unwanted thing — I want to cup it in my hands and tell it: Do not be afraid. Do not rend yourself. Do not falter. I’m here. I will stay with you, just a little longer. And so I answer to it, and so I will answer to it for as long as my body allows. This is the name with which I tell my mother I love her. This is the name by which my mother summons me. Whenever she does, she slurs the words, spits a little. Every time, it sounds like singing.

1 “But I’m the one who has money; you don’t have money.”

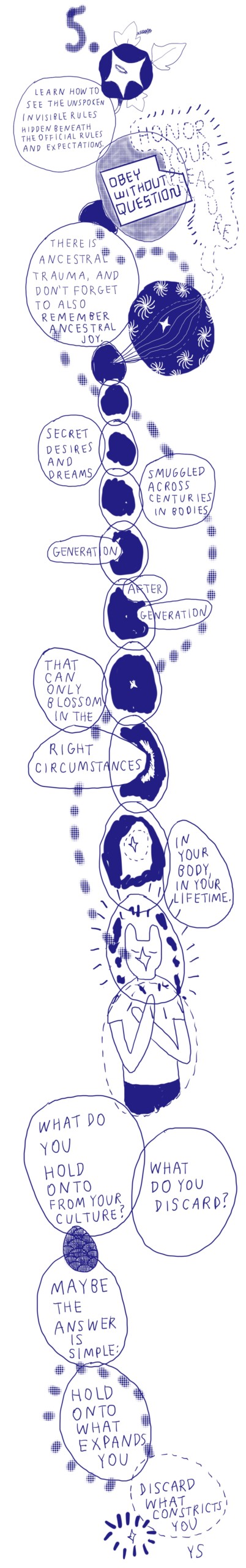

Mourning the Loss of Indigenous Queer Identities

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

![]()

I recently came out as gender-fluid, straddling the Western gender binary like it’s about to give me the ride of my life. I grew up hearing that I looked more like a boy than a girl, all while being told how I’m too feminine to be a boy. For a while, I thought that was me just being bisexual, though I could never settle into that identity. It was somewhat right but ultimately wrong because labeling my sexuality didn’t feel like enough. I tried pansexual, and after that, I was just queer for a while. Nothing settled. I thought I could find myself somewhere in this rainbow of colors, but something just always felt off.

That bizarre feeling is something that’s a staple in my American life. I say this because there’s still a degree of separation there, like the dash between Asian and American. It’s a zealous reminder that I am somehow incomplete, that the words I’ve chosen to describe myself are not enough. In each moniker, be it bisexual or pansexual or queer, I searched for some ounce of truth to who I am. And as I grow older, I find it more difficult to truly accept myself because I don’t feel like I have the right words to describe myself. It’s taken me years to realize that I likely never will.

I am part of the Filipino diaspora, though my identity is entirely defined by a strictly Western perspective. I am an immigrant, my English is so good, and the words I’ve used to describe my gender and sexuality are words I learned from Americans. There are parts of myself, however, that cannot fit within the confines of Western language. Words have a history and language has connotations that go beyond definitions. English is a colonizer’s tool, so it does not always have the right expression for who I am. As an immigrant, I thought perhaps that looking back into the history of my people would give me a better way to express my identity.

![]()

Growing up in the Philippines, words that meant “gay” and “weird” were always synonymous with each other, and bakla was used to describe the sinners who couldn’t be nailed down by “gay.” My mother and her mother, my Lola, were both devout Catholics. They taught me that Jesus hates The Gays and Probably the Baklas Too in tired monologues ripped straight from our local priest’s mouth.

Someone wrote about the word bakla in The Guardian and how maybe Western members of the LGBTQIA+ community could learn a thing or two from Filipinos. Bakla is our third option, they claim, but even then, it’s not a label: it’s a standalone concept, kind of a catch-all for anyone who isn’t strictly man or woman, gay or queer, and one that Western minds should embrace. And I might agree to that if I wasn’t still so incensed by the fact that we ourselves don’t have a better understanding of the term bakla at all. There is no need for the Western gaze to embrace that fact now because they never did in the first place. Why offer up more of ourselves when the rest of the world has already taken so much from us?

Illustration by Leanne Gan

The Philippines is a beautiful country, but it is a world where nothing, not even our language, was nailed down or set in place because our people are so deeply traumatized from centuries of imperialist brutality. We spoke Tagalog with English and Spanish mixed in. Some of us knew other languages, such as my Lola’s Ilocano, though these languages were not widely taught. I was only told that Ilocano was an old language and that nobody except my Lola could speak it in our family. I learned about how wonderful the U.S. was for saving the Philippines from the Japanese during World War II. At the same time, I constantly heard about how unhappy we were that Americans continued to meddle in our government.

Our collective consciousness mirrors our country’s muddled history. The Philippines I knew was a mashup of the charming East and a forceful West. Lola would occasionally tell me stories about her father, about how the Spaniards were terrified of our people, about how I was one of the last of the Ibaloi Igorots. Our people, according to her, were simple farmers and warriors. We used every part of the animal, always prayed to the land and gave the Earth our respects. Apparently, when outsiders first came to our shores, we welcomed them with open arms.

But we were uncivilized. Lola would cite that marriages were not “sacred” to our people before the Spanish came. Our people were wayward. Our warriors were never strictly men, as they should have been. Women may have laid with other women in “unnatural” ways and so did men. There were probably even people “in between,” though that concept went beyond What God Intended. And though the Spanish tried to “correct” this through the word of their god on their muskets, we would kill them too easily when we felt threatened, which Lola would say was “unfair.”

Though we had taken them in, they always called us savages once they got back to their homelands. We were easy pickings since we were so naive not to see the value in our fertile lands the way that the Europeans did. Our soil was perfect for sugar and tobacco. They did not understand how we had so much gold in our mountains but did so little with it. They thought our mangoes and purple yams were the perfect exotic treats, served up on the backs of the few of our tribesmen they took back to their countries in chains. And the location of our islands were perfect for taking on the East Indies spice trade by storm.

The Spanish were the first to take over. The Dutch sent missionaries on Spanish naval vessels, aiding in the efforts to civilize us. Americans took part in their imperial games and proceeded to “steal” us away. By the second World War, we were finally called a “nation” by the Japanese and Americans who pillaged our homes. But by then, we were broken. Entire cultures that had coexisted for ages were wiped out within a century of constant war. Most were murdered in their homes. Some were dragged abroad in chains and cages to be shown off like animals at carnival exhibits. The Catholic God replaced all of our deities, especially the genderless and intersex gods. Buried alongside countless slaughtered natives were languages that no one cared enough to understand or preserve. The word bakla became an umbrella slur with a history no one can remember.

No one wrote down what happened to the people before my Lola. She didn’t have a birth-certificate because that’s how turbulent things were in her childhood. No one knows who my ancestors were, if they believed in genders, or what their sexuality was. Now my Lola is long gone. I can’t ask her.

But the death of our people, our cultures and the true history of our people is a slow and painful process.

But the death of our people, our cultures and the true history of our people is a slow and painful process. Many miles north of where my Lola and I said goodbye for the last time, tourists drive up the mountains to meet Whang-Od Oggay. She is the last of the Kalinga mambabatok, a tattoo artist within her old tribe, and the tattoos she puts on these tourists were meant for the Butbut warriors who fought to defend our people. Those warriors are long gone, but these travelers will go back to their home countries to complain about the smell of our food. They will return West, where they scoff about immigrants stealing their jobs. Those tattoos are just reminders of an adventure that never happened and a people they will soon forget. History is not kind to the losers, but modernity is worse.

This is the legacy of colonization. It is far more painful than knowing just how many millions were murdered because they weren’t good enough for others to accept. It is the mass extinction of identities and languages that can no longer exist because someone else said they were bad.

We only vaguely remember our ancestors being warriors and forget that they died in horrific ways. Their efforts to save their countrymen or fight for their freedom will be watered down to tactical studies for soldiers and myths of bogeymen hungry for blood. No one will bother to spell their names correctly, if at all, let alone remind the world that many among our ancestors were people who were beyond “queer.”

Children are born into their people’s slow and steady massacre and are given “better” names. They are told they are either boys or girls and that’s all there is to it. Schools teach them that their ancestors were barbarians. The society cobbled up around them tells them that their desires must adhere to the rules of their colonizer’s beliefs. They learn that their nation is in ruins, and that it’s better to live somewhere else. When they do live elsewhere, they stop speaking their language. Ilocano is ugly, after all, and so is Tagalog, so it’s better to speak English.

Our identities are built on the graves of perspectives that would have better embraced who we truly are. We gladly spit on them when we leave, but look back with sorrow only if we realize just how much we’ve lost and continue to lose.

![]()

I was taken away from my homeland so my mother could find “better opportunities” for us in the States when I was seven years old. In elementary school, white classmates would pick on my “smelly food” and spread vicious rumors that I ate the neighborhood cats. The Philippines was mentioned once in only one of my history classes my junior year of high school. If I ask my friends now what they know about my home country, they ask me how to say “Duterte.” My spouse will tell me about how his mother has traced their family’s name back centuries. And if I google my name, the Brazilian singer I was named after pops up. At home, we only occasionally eat Filipino food because some dishes are almost impossible to make without an hour-long trip to the nearest Filipino store. If my elders speak to me in Tagalog, the best I can do is shake my head and enunciate that I can’t speak it anymore.

Somewhere along the way, I’ve become less Filipino. I am part of a diaspora. This is supposed to be “normal.” Immigrants are bound to naturalize themselves in their new countries. We work on our accents by speaking our colonizer’s languages more than using the tongues we were born to speak. We form better relationships with the “natural” citizens of our foreign homes. We move forward, we continue to forget, and we cannibalize ourselves even more to fit into molds that were never intended for us.

In the Philippines, a large part of our identities are defined by the gender binary of the West. Many in my home country, just like my Lola or my mother, believe we were “saved” by their civilization. It took me years to realize that salvation was just slaughter. The right words for who I am died along with our people, our cultures and who we could have been. We were whittled down to little more than a passing mention in a history book. I’ve already lost so much before I was even born, so there should be comfort in the cold logic of assimilation and taking part in the agonizing death of a people.

![]()

I am non-binary. I am queer. I am one of thousands of Filipinos who have left the Philippines. When labeling my sexuality, I still write “queer” because I don’t know what else to say and bakla feels like a slur. I suppose I have the vague luxury of separating my gender and sexual identity from my race if I don’t think about it too much.

This is the best that the West has to offer me after all this devastation. For this identity and language, I am not content. I never will be.

These Portraits Depict the Radiance of Asian Trans Leaders

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

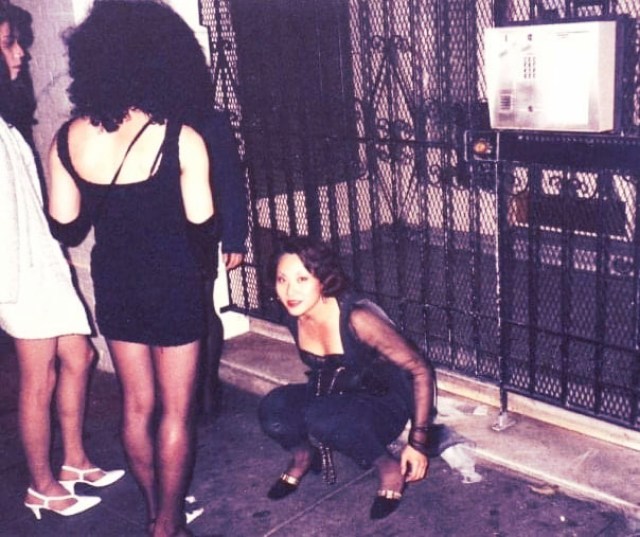

![]()

As a Vietnamese trans femme, the threat of a violent encounter looms over me constantly, like the swinging sword of Damocles. There is an invisible toll that many trans people are forced to pay daily. The price to be authentically ourselves means facing the most direct forms of violence in the wake of a brutal world. More recently, with the increased targeted attacks on Asian Americans, this real threat has seemingly increased twofold. Being far too familiar with the language of violence, it is important to state that these manifestations of hate are continuations of a historical legacy.

The same mechanics that perpetuate hatred against Asian communities are the same ones that endanger the lives of trans people. As both trans and Asian American activism each reach a so-called “tipping point,” we must sharpen our understanding of how the two are connected.

I want to dignify those in our community as trans Asians who are getting us closer to a liberated world. For this portrait series, I was inspired by Jose Barboza-Gubo’s own photo series, titled “Virgenes de la Puerta”, which elevated the role of trans women by depicting them as saints and religious icons. Each portrait is done in a different style – both to push my own personal boundaries as an artist, but to convey a particular character from the subject.

It is crucial to celebrate our lives as trans and Asian people, and uplift each other wherever possible. Within this particular moment, who else may tell our whole stories, beside ourselves?

![]()

Sasha Alexander

Artist, Educator, Healer

“As a nonbinary trans Black South Asian person and as an adoptee so many of my ancestors/names have been stolen from me. As a result of the state’s refusal to accept my right to information and upon the trauma that my ancestors navigated across oceans and lands, I do this work as a seed nourished by the sun and moon and water of their spirits and their struggle. I work as celebration in sake of their names, tongue, and histories for futures, pleasure, rest, care, accountability, and to nourish possibilities of mine and theirs; our histories woven. I do this work for Juan, for Phoenix, for L.L., for the many transcestors who loved me and guide me, for all of us who will be ancestors one day hopefully having made the world a little sweeter, more joyful, sustainable, and just.”

![]()

Loan Tran

Storyteller, Educator

“Home is south. Big and brilliant and messy. It is where my people are, they are my refuge. Home is laughing and crying and apologizing and kissing and messing up over plates of food. It is me belonging to more than I could ever imagine, to more than myself. It is the miracle and hard work of family. Home: Slow Sundays, sitting in the sun and relying on the inevitable breeze to come.”

![]()

Andy Marra

Human Rights Activist, Strategist

“It is with profound love for my community that I have committed my life’s work to social justice so future generations of trans and queer people inherit a world that our ancestors could have only dreamed of.”

Fei Mok

Climate Policymaker, Artist, Community Organizer

“As settlers of color on indigenous land, it is important not just to acknowledge the history of colonization here on Ohlone land, but also our role as settlers and visitors. Our liberation as people of color is intimately tied with the liberation of black and indigenous peoples and this includes return and rematriation of land and reparations.”

![]()

Trang Tran

Healer, Food Historian

“When I think about what liberation tastes like, canh khoai mở (yampi root soup) comes to mind. A simple soup with earthly flavor and mucilaginous texture. The longer you simmer it, the sweeter and better it tastes.”

Richie Shazam

Model, Photographer, Media Advocate

“The goal of all of my work is to center the needs and the vision of my queer family. My work, whether it is my photography, modeling or show Shine True, is not only about representing queer and trans people. It is about building a space for us to flourish, heal and grow.”

![]()

Meredith Talusan

Author, Editor, Journalist

“It’s been difficult for me to envision the future for us in the wake of so many challenges to our communities, but what gives me solace is the knowledge that so many of us are descendants of peoples who believed not only in our humanity, but in our sacredness. Whenever I face challenges to my existence, I recall the spirit of my ancestors whose wisdom grew out of their existence beyond prescribed gender.”

Kiyomi Fujikawa

Community Organizer, Movement Builder

“I’ve found joy in building up the new worlds we want to see, creating new models out of our care, love, and commitment to each other. The experiments, the failures, the learnings are all a part of the process. I find the joy in the trust and grace that we’ll keep practicing tomorrow and the next day until we are all free.”

![]()

Kai Cheng Thom

Writer, Performer, Social Worker

“I’ve been going through a profound shift in how I relate to the world personally and professionally. This past year, I’ve stepped away from work as a conventional mental health professional and into the realm of coaching, conflict mediation, and group facilitation. I’ve had to let go of a sense of knowing who I am professionally and plunge into an unknown space in order to rediscover what I’m called to do with my life. And this professional transformation is rooted in a deep personal process as I struggle to bring the notion of ‘choosing love’ off the page, out of the theoretical, and into the world as an actual practice. It’s scary and I love it. I’m terrified and in some ways, I have no choice. I embrace this unfolding.”

Alex Iling

Sexuality Educator

“We can bring pleasure to our social justice movements by reimagining our own relationship to pleasure itself. Learning to create space for pleasure feels similar to creating space for hope, rest, and resilience. It reminds us of what is possible to experience and why we keep moving forward.”

What You Think A Woman Looks Like

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

![]()

I look like what you think a woman looks like.

Okay, that’s not fair. I don’t actually know you. What I really mean is: Every time I leave my apartment, someone calls me “miss” or “ma’am” or “lady,” even in trans-inclusive spaces. I am invited without hesitation and accepted without question into women’s circles. I offer my pronouns and receive immediate reassurance: I am welcome, my truth is welcome, my pronouns are welcome. Plenty of women who don’t look like me aren’t granted the same courtesy. Women in many of my friend groups casually refer to our group as “ladies” or “women” or, at one point, “girl gang.” Occasionally they remember me and apologize after the fact. More often, it doesn’t occur to them. I don’t blame any individual person for this. It happens with everyone, regardless of their heritage or gender. If I met me, I’d assume I was a woman, too.

It’s obvious that there’s an F on my birth certificate. My cheeks are full and rosy, my body all curves and flare: narrow waist, broad hips, small but prominent breasts. (Extra prominent because bras give me dysphoria.) For some people, that’s more than enough to make the assumption.

For others, it’s the long hair. Long nails. Long, flowy, colorful clothes. My wardrobe is a mess of odds and ends. In cold weather, I mostly wear black pants and men’s shirts, while the warm weather brings out a sea of colors and patterns. My favorite skirt reminds me of a garden: it is a long, shining green wrap skirt, plain on one side, shimmering with blossoms on the other. Mostly I wear pants, even in summer, but they are loose and brightly patterned, which Americans also associate with women’s clothes.

And the assumptions run deeper than how I look. I love cooking, and especially feeding people. I love talking to people about their feelings. (I’m a ghostwriter and a somatic coach, which means I spend a lot of time being paid to talk about people’s feelings.) I love kids and bunnies and lilacs. I swing my hips when I dance. I sing often and laugh loudly and cuddle frequently. I am the classic Mom Friend, complete with the constant exhortations to stay hydrated. Of course, none of these are exclusive to women, but they are certainly associated with them.

As an AFAB person in the U.S., being seen as nonbinary requires being seen as masculine. A rigid, colorless form of masculinity, defined primarily by what it’s not. Skirts, not allowed. Flowers, not allowed. Softness, not allowed.

Illustration by Althea

![]()

Masculinity in India looks very different. Certainly, there are requirements and restrictions, probably more than I’ll ever be privy to, as someone neither raised in India nor treated as a man. But I’ve observed that men in India are expected to be expressive in ways men in America are not: to laugh, to dance, to hug.

My loud, muscular dad has always been considered manly. Like me, he sings often and is aggressively hospitable — in India, these are seen as masculine traits. (Women are also expected to be hospitable, but not aggressive about it.) My dad also takes great pride in filling his backyard with colorful roses, and no one has ever questioned the manliness of that.

Plenty of my colorful, flowing clothes are men’s clothes from India or Thailand. I have bright kurtas, Indian men’s tunics, and loose men’s pants from Thailand patterned with feathers or elephants that are also popular in India. In the U.S. these would be considered feminine, but in India they are somewhere between masculine and gender-neutral.

Indeed, to my family in India, I am shockingly unfeminine. I’m not as social as women are expected to be; I don’t say yes as often as women should. And I certainly don’t engage in any of the endless grooming and dressing expected of women. Even my long, wavy hair is considered unfeminine, because I neither straighten nor curl it.

If the aesthetic of masculinity in the U.S. is often defined by what is not allowed, the aesthetic of femininity in India is defined by what is required: makeup, “hygiene” (which could better be described as a war on hair), modesty, fitted clothes.

My nieces and their moms are always asking why I don’t do the things women do. Questions like: Why don’t you tweeze your eyebrows? Why don’t you wear makeup? Why don’t you dress up? Why don’t you shave? Why do you sit like that? Why do you travel alone? Why do you say ‘no’ so much?

Of course, they don’t consider the possibility that I’m nonbinary. India legally has three genders, and a broad swath of identities fit into India’s third gender, but the assumption by cisgender people is that the third gender primarily consists of AMAB people who present in a feminine way — a box I don’t fit into at all.

I used to ask questions back: Why not? Why should I? Why do you?

The answer tended to be, Because you’re/I’m/we’re A GIRL, so I stopped asking.

![]()

When I was a kid, it was easy. I wore shorts and a t-shirt, cropped my hair short, rode a bicycle. My little brother called me bhai — big brother. No one questioned this: if there’s one thing Americans and Indians seemed to agree on, it’s that a tomboy phase is no big deal, as long as you grow out of it.

The struggles started around puberty. I successfully argued out of wearing makeup, and I (briefly) surrendered to wearing bras, but the biggest battleground was jeans. I hated them. They itched, they pinched, they reminded me that my body was changing without permission. My dad took me shopping regularly for jeans, and I hated all of them. Sometimes they were too tight on my hips, sometimes they were too baggy on my legs, sometimes they fit perfectly, and I had no vocabulary yet to explain why that was the most uncomfortable of all. To this day, jeans feel like prison. They also, for reasons I’ve never been able to articulate, feel like gender.

I went to college on the other side of the country. Suddenly I had no family around to tell me how I was supposed to look. My campus had an enormous queer population, and maybe as a result of that, many of the cis straight people also freely experimented with clothes and gender expression. For the first time, I could look however I wanted. But I already had clothes, and no money to buy new ones, so I didn’t change my look overnight: I just put away the clothes I particularly hated, especially the jeans.

My best friend, a white cis girl who rarely wears makeup, who wears her hair long because it makes her feel like a princess and always paints one nail a different color than the others because Cosmo told her it would pop (it took months for me to figure out if she was being facetious), introduced me to the joy of long skirts. The first time she lent me one of hers, it was a revelation: a floor-length peasant skirt with enormous rainbow stripes. It was soft and colorful and it fit, no matter what shape I was. I remember standing in the college courtyard, spinning and spinning, and marveling at how the fabric lifted and fell, never restricting my movement or clinging to any curves I wasn’t comfortable remembering I had. To this day, floor-length skirts feel like freedom.

For years of college, I borrowed her clothes regularly. She bought me a floor-length peasant skirt similar to hers, in bi flag colors, and I romped around in it gleefully, even in the winter, over very thick leggings. I tore and re-stitched it many times before fully wrecking it during a snowball fight, stomping right through it with my boot as I clambered out of a pile of snow. I was oddly delighted by the loss: what a fun way for a skirt to die.

When we graduated, my friend bought me the beautiful green wrap skirt that is my favorite piece of clothing. I haven’t torn it yet, but if I do, I hope it’s for an equally fun reason.

![]()

I never really wanted to come out as nonbinary. I’d already gone through the exhaustion of being an AFAB bisexual with a cis boyfriend and of being a person with multiple invisible disabilities and of being multiracial but not quite looking like any of those races. I didn’t especially want to go through defending one more aspect of my identity.

Then my office started asking us to put pronouns in our email signatures and to introduce our pronouns at the beginning of meetings. It had been easy enough to just never say anything one way or another, but actually writing she/her felt like a betrayal of something deep. So I put they/them at the end of every signature, introduced my pronouns as they/them at the beginning of every meeting.

No one treated me any differently, mostly because no one seemed to believe me. In my theoretically queer-friendly office, no one ever remembered my pronouns on the first try. When people listed the women in the office, my name was inevitably mentioned. My very last email to my former boss, sent after I had already resigned, was the single line, “Friendly reminder that my pronouns are they/them and have been for over two years now.”

Of course, I tried the short hair and the men’s clothes. I was pretty into them, especially when my hair was just the right length to go fwoop whenever I shook my head. But the part I wasn’t into was not wearing skirts for a full year. I missed them. I missed color. I felt restricted again, in a way I hadn’t since high school. My plain black pants always felt too tight. When summer came, I looked at people in lovely flowing skirts, purple and pink and tiger-striped, and wished I was wearing them.

And then I got mad at myself, because who was stopping me? Theoretically, coming out as nonbinary should have meant freedom, but I’d just shoved myself into a different box, desperate to feel like a “real” nonbinary person the way I’d never felt like a real woman.

So I took my skirts back out.

![]()

Coming out to my friends was a relatively easy process. My friend group is mostly Ashkenazi and East Asian, mostly queer, and heavily nonbinary. Some of them forget my pronouns more often than others, but most of them remember most of the time. Only one friend actually said to my face that she didn’t believe me: she said I just didn’t like the restrictions that come with being a woman. As far as I’m aware, no one likes the restrictions that come with being a woman.

Slowly, steadily, beautifully, people across the world are fighting to shift the boundaries of what masculinity and femininity look like. They’re fighting to acknowledge that masculinity is not exclusive to men, nor femininity to women. Some will say nonbinary people hurt that cause: that by rejecting the gender assigned to us, we’re rejecting the battle to broaden gender for everyone. You probably won’t be surprised to hear that I reject this argument. Prescriptive, exclusive views of gender hurt everyone. Nonbinary people are hardly immune from restrictions or expectations. Ideally we reject those restrictions and expectations, but I want everyone to do that. I want everyone, cis or trans or otherwise, to seize the same freedom I did.

Recognizing that I was never going to fit comfortably into my American peers’ idea of masculine or my Indian family’s idea of feminine meant freedom to throw out both scripts and write a new one. I laugh, cry, cuddle and bask in color in ways men in the U.S. are not expected to — and I think men in the U.S. should, too, if they feel like it. I don’t tame my hair, voice or opinions the way women in India are expected to — and I don’t think they should, either, if they don’t feel like it.

Someone’s always going to be unhappy with the way you look, talk, and act. That someone shouldn’t be you.

How Tam Found Empowerment in the Closet

Welcome to Autostraddle’s AAPI Heritage Month Series, about taking up space as our queer and Asian/Pacific Islander selves.

![]()

Many queer people find incredible strength and power in the act of coming out fully as themselves. While being able to show up as our full queer selves in our lives is a very beautiful thing, it can also be a lot of pressure to craft the perfect official coming out. This is especially true for aromantic and/or asexual folks, who still lack a societial template to navigate their sexuality, and for queer Asians, for whom coming out has communal repercussions. So what are you to do when you are a Vietnamese asexual and aromantic woman who grew up in white, cishet, francophone-dominated Montreal in the 1980s and 1990s?

This is Tam’s (not her real name) reality. I first met the 38-year-old office worker in a Montreal-based Asian group, and was struck by how open, upbeat and talkative she was. So getting to sit down with her to candidly chat about her journey navigating her asexuality and aromanticism was an absolute blast. Over many laughs, we discussed her confusing process into finding her sexuality, her dating adventures and how she came to find empowerment in the closet.

Illustration by Joyce Chau.

![]()

To start, can you tell me how you identify in terms of gender and sexuality?

Cis female, very straightforward. I am the only Asian who is aromantic that I know of. I have not met another person who’s Asian and asexual. And I haven’t met another person who is aromantic in Montreal. There probably is someone, but I’ve not met a single person.

Tell me about your journey navigating your sexuality.

This journey was very much externally motivated. Because, being aromantic, I didn’t give two fucks. I already had close friends and family who responded to my emotional needs. I understand romantic people desire that sort of connection with another person, but I never looked for it myself. So until puberty, I just thought I was different, but I didn’t think about it much more than that.

It started becoming a more pressing part of my life when people started asking me out because I didn’t want to go on dates. So I started wondering why. At 18, I didn’t realize there was such a thing as asexuality. So I just thought I was bisexual because I really didn’t care which gender was asking me out — I just didn’t want to date. I concluded that since I didn’t care for either gender, I must have been OK with both.

At 21, I found a site called AVEN which was, and still is, the main site for asexual people. I ended up on that site, and realized I was asexual. I still didn’t date anybody, so beyond that, I didn’t think much about it at all

When I was 25, my older brother and my dad sat me down separately and advised me to try dating. Taking their advice, I started dating. I had one short queer relationship and one long term queer relationship, even though I dated guys as well. I dated my first girlfriend for four-ish months. That ended not very great, but we’re still friends. I still hang out with her, her kids and her husband.

Then I dated my second girlfriend for close to five years. This is when I realized that I was aromantic because even though I loved her very deeply, the intensity was very different. When romantic people do something nice for their partner, they feel warm inside. Their partner appreciates it and feels warm inside too. I don’t have that feeling. I’ll do something nice for you, it’ll be like a fist bump. And that’s the end of it! I would do the same thing for my family or any of my friends. I’ll shower people with love, but that intensity is completely absent.

Even though she was willing to let that go to stay with me, I didn’t feel staying together was fair to my partner because she wanted somebody who was equally as intense. But I only had platonic feelings, so I made the choice to end that relationship — I was 33, understanding I was aromantic. I realized it was not the best idea to be in a relationship because I don’t have the same capacity for feelings as romantic people. My emotional intensity doesn’t go in that direction.

Have you been dating since?

I never wanted to date to begin with. I tried it, and I have determined that it’s not for me. I have not been on any dates since. I’m not closed off to meeting people, but I make it very clear from the beginning that I’m just not interested in a romantic relationship, mostly because they will be disappointed. They’re going to see that there’s something lacking immediately.

So you don’t date, but I understand you were very involved in the club scene. A lot of people in the queer community criticize it for being very heteronormative. What was your experience like?

At queer clubs in Montreal, heteronormativity is not an issue, but fetishism is a huge problem. Like, oh you’re Asian, you look queer, you’re a girl? People have a fetishized idea of Asians. And I’m not gonna point fingers at queer women or at straight men because everybody has fetishized ideals of queer Asian women. Even a resting bitch face can only get you so far. Some people are very persistent. You can look like as much of a bitch as you want, but sometimes that’s also a fetish. What are you gonna do?

How do people react to your queerness in Montreal?

That’s a loaded question. For the most part, people are either indifferent, or very nice about it. However, one time, at work, I was at the pride flag raising event of my company. When I sat down, this lady started making pointed homophobic comments while photographers were taking pictures of us. Then, she told me that she was my ally. Since I don’t share my personal life with colleagues, she was making an assumption about me, waiting for me to confirm her suspicions. It happened because I present myself androgynously at work. It was a very negative experience.

I reported her. Now she walks on eggshells around me, and I’m OK with that. She’s still employed, and as long as she doesn’t bug me, I don’t care. The only reason I reported her is because I don’t want her to do that to other people, especially [since she is in] upper management. She didn’t hurt me at all, because I have had to deal with much worse in my life in terms of racism. So what I experienced with her is half as bad as the things I’ve lived through as a person of color in Quebec.

I think what comes up again is that you get more flak for being Asian than for being queer.