Study Claims Literature Becoming Less Emotional, But Maybe It’s Actually Just Less “Moody”

Are the way we write books changing? Certainly – as changes in the world at-large would likely lead to changes in its art, since art reflects life. But just how much? A new study from the UK, out of the Universities of Bristol, Sheffield and Durham, and published in the research journal PLOS ONE, posits that literature has changed dramatically since the 1960s in one key area: emotionalism.

As Jezebel covered this story on Thursday:

“You know that feeling you get when you are reading a book and the language is so emotive and beautiful that it makes you want to break down and weep? Unless you’re a fan of the classics, probably not. A new study… shows that literature over the past 100 years has become increasingly emotionless, unless that emotion is fear, in which case we modern folks loooove being scurred.”

How that study seems to define it is based on the presence of certain “mood words.” As Jezebel writes, “Using Google’s database of more than five million digitized [sic] books, researchers did searches of mood words that fell into six categories (anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise) and charted the frequency of their use in literary works from the past century.” The result seemed to be that, with the exception of those related to fear, the number of these “mood words” in literature is decreasing.

It’s easy to take a study like this, and think, as one Jezebel commenter put it, “Oh, for pity’s sake. Scratch an academic, find someone who’s mourning the death of literature.” Yet, if people do seem to want to read more about fear and less about other emotions – or that writers aren’t writing as much about things other than fear – that does suggest an important shift as a society. Lead author Dr. Alberto Acerbi notes that “periods of positive and negative moods often correlated with historical events…The Second World War, for example, is marked by a distinct increase in words related to sadness, and a correspondent decrease in words related to joy.” If there is indeed this reported change, it likely says something significant about the history of the last half-century.

But that’s if the study’s conclusions are correct. For starters, when we say that our books are less emotional, which books are we really talking about? If anything, maybe this is more the case in best-selling books because a lot of the specifically “moody” books – like romances, for instance – have been shuffled off into their own genres. As with music, as markets have gotten bigger since the middle of the century, there have been more and more ways for specific interests to be segregated into their own corners of the bookstore.

The article mentions the popularity of dystopian fiction, specifically The Hunger Games, the latest YA series to gain massive crossover appeal with adults and its own, big-budget series of movies and pop-culture tie-ins. Jezebel writes that the prominence of fear-based language is “a fact that’s hard to argue with when you consider just how much of successful literature recently has to do with dystopias, monsters or kids forced to murder one another in giant arenas.” But before there was The Hunger Games as the top-selling YA series out there, there was Harry Potter, which, while certainly very dark at times, wasn’t exactly dystopian – and made it clear that while our heroes were fighting bad guys, they were still ordinary teenagers deep-down, full of ordinary teenager hormones and able to have ordinary teenager relationships and high school drama (see: Half-Blood Prince).

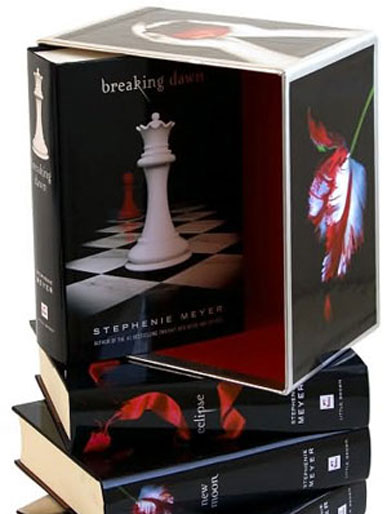

And in between the two, there were the Twilight novels. I’m not going to argue that they’re great literature, but when people talk about how those books are written like “bad fanfiction” (and they are), what they mean are how emotional and descriptive the books are. And yet, those books’ “purple prose,” as some writers call it, didn’t keep them from selling like hotcakes. Romance novels in general may be a niche genre, but Stephenie Meyer proved to us that plenty of people are willing to read that kind of language even outside of that specific market.

In many ways, the last decade has been a triumph for genre fiction. This is most apparent in television – it’s hard to see a historical drama like Mad Men or fantasy like Game of Thrones taking off as they have twenty years ago, enough to spawn imitators – but it’s true in literature as well. Sci-fi and fantasy, romance and other genres that would normally get buried deep in the stacks are now on the bestseller lists, even for adults. (The rise in the YA genre in particular – largely thanks to the success of YA bestsellers like Harry Potter, Twilight and The Hunger Games that had large numbers of adult readers – has helped this along. YA has always been more friendly to niche genres, and has such become a fertile ground for experiments with those tropes even outside of the realm of speculative fiction – such as with John Green’s highly-acclaimed take on sick lit, The Fault in Our Stars.)

The Jezebel take points out that one “might push this even further and say that a lack of emotional language in a book doesn’t mean that the work is in itself emotionless.” Indeed, positing that we are “a more visual culture” could explain some of the shift in language; perhaps writers today simply prefer metaphor and simile to describe beauty or love or pain, rather than literal words associated with those ideas. Twilight is a good example that, in yet another similarity to fanfiction, uses a lot of (often clichéd) metaphor to describe characters’ beauty; Edward is frequently referred to as “an Adonis,” for instance.

A lot of this could have to do with the fact that there is a wider variety of people writing novels today than there were fifty years ago, as education in general has become more widely available. For example, a majority of high-school graduates in the United States now go on to college, which was definitely not the case in the 1960s. The increased exposure to different types of literature and greater development of writing skills that come with higher education, while hardly necessary to become a novelist, are likely to push more interested young people into the profession. As such, because more and more people have access to those resources, we’re seeing a greater diversity in who gets published – and thus, a greater diversity of writing styles. It may simply be the case that there was more of a “standard” for “moody” writing back in the 1950s and 1960s, whereas now, we have a greater variety of writers with more unique takes on how to convey emotion in literature, which may or may not include easily analyzed “mood words.”

One of the more interesting things about the study is how it indicates that the 1960s is “the precise moment in which literary American and British English started to diverge.” The study press release speculates that “the baby-boom and the rising of counterculture” may have something to do with it, though it’s not like the UK didn’t experience both of those things to its own, lesser extent as well. The larger gap in economic prosperity between the two countries in the post-war period may be a better explanation; as the press release explains, “In the USA, baby boomers grew up in the greatest period of economic prosperity of the century, whereas the British baby boomers grew up in a post-war recovery period.” This is a point that has been made relative to other art forms as well; New Yorker music columnist Alex Ross discusses this in his book The Rest is Noise with regard to differences in European and American postwar classical music. This also brings the issue of privilege back to the forefront; one of the co-authors speculates that “perhaps ’emotionalism’ was a luxury of economic growth.”

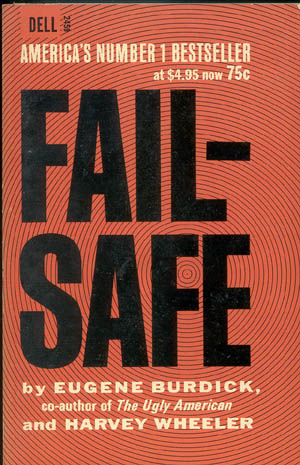

Fail Safe by Eugene Burdick, a nuclear war thriller from the early ’60s, via lib.uiowa.edu

The increase in fear-related words is just as fascinating to examine. The mid-to-late 1950s and 1960s were around the time period when paranoia about nuclear war, in the wake of the Cold War weapons race, really started to kick in and become a popular theme in fiction; before that, Americans in particular had a more positive view of “the bomb” in the wake of its use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to win World War II. Now the Cold War is over, but it’s not like we haven’t had new reasons to be paranoid since 1989, especially with the War on Terror and even before that, with atrocities such as the ethnic cleansing wars in the Balkans in the 1990s. Or ongoing environmental threats like global warming. And of course, nuclear weapons are still out there and just as deadly in the wrong hands – as the latest panic over North Korea’s nuclear threats has shown us.

Regardless of what conclusions to draw from this, the fact is that changes in the modern world – from political factors like wars and revolutions, to more gradual, social issues like the extent of economic and social prosperity – have changed the way we write, and think about literature. The press release notes that changes in emotionality of words “are a signature of different style periods in the history of Western literature,” and indeed, Western art has long been defined by pendulum swings between emotional expressionism and rationalist restraint. The current trend likely won’t last forever, but regardless, it’s time to stop judging today’s literature by the standards of a past to which we can never return.