Our Legacy: Six Lesbian Magazines From The Then Before Now

In the mid-twentieth century, as gay men in urban areas began forming communities and meeting each other via the sexual subcultures prospering in bars, bathhouses and outdoor cruising spots, lesbians started communing around a more cerebral common ground: READING! Over time, women’s bookstores were joining bars as THE central place to meet other lesbians and meanwhile, feminist and lesbian-owned printing collectives were popping up all over the country. And, obviously, groups of ambitious dykes all over the land gathered with one another to create magazines they hoped could change the world. I can relate to this desire!

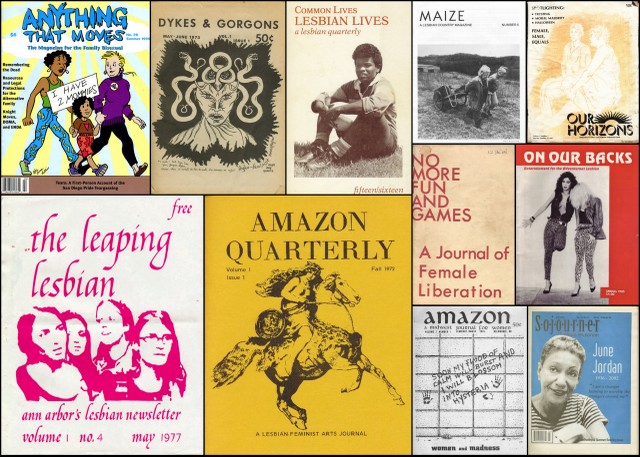

Many of these magazines have faded into obscurity or barely breathed at all, unfortunately. This is particularly tragic because some of these situations had amazing names. There was Boston’s radical No More Fun and Games (1968-1973), Chicago’s Killer Dyke – Lesbian Separatist Magazine By The Flippies (Feminist Lesbian Intergalactic Party) (1971-1972), Iowa City’s Better Homes and Dykes (1972-1982), Maine Freewoman’s Herald: a mostly lesbian journal (1972), Brooklyn’s Echo of Sappho (1972-1973), Berkeley’s Dykes and Gorgons (1973-1976), Columbus, Ohio’s Purple Cow, Minneapolis’ So’s Your Old Lady (1973-1979) and The Salsa Soul Sisters/Third World Women’s Gay-zette (1976-1985), among so many others.

Most of these defunct lesbian journals didn’t accept advertising from corporations, charged as little as possible for their publications and encouraged women to share their copy with others who couldn’t afford it. Continued publishing was enabled by passion and gumption and a desire to create social change. Subscription costs rarely covered even basic expenses, so funding often came from the writers themselves and many publications survived with the help of financial gifts from supportive lesbian fairy godmothers. Clearly we continue on in this spirit today.

You can find many of these publications at various University libraries all over the country, but there are a few you can actually find out more about right here on the internet, and those are the ones I’ve chosen to focus on today.

+

6 Old School Lesbian Magazines You Should Know About+

_

1. Vice Versa (June 1947- February 1948)

[read online at queer music heritage]

It all started with Vice Versa, subtitled “America’s Gayest magazine.” Launched in 1947 in Los Angeles, the magazine was headed up by a secretary who went by the name “Lisa Ben” and produced the magazine at the office she worked in. Ben hand-typed the magazine using a manual typewriter and created multiple copies by writing on carbon paper. Ben didn’t want to sell Vice Versa, she just handed it out to her friends with instructions: “When you’re through with it, please pass it on to another lesbian.”

The magazine talked mostly about books and movies and music, in some cases even essentially “recapping” a book that readers might not be able to find in their own libraries due to censorship of queer materials. Ben had trouble finding contributors for the new magazine and usually ended up publishing everything that came in to her office so that she wouldn’t hurt anybody’s feelings. Ben shuttered the publication after nine issues because the office she worked at closed, and her new job didn’t give her a chance to secretly make a lesbian magazine. It was difficult to meet other lesbians in those closeted times, but Vice Versa enabled Ben to do so, and, well, vice versa.

+

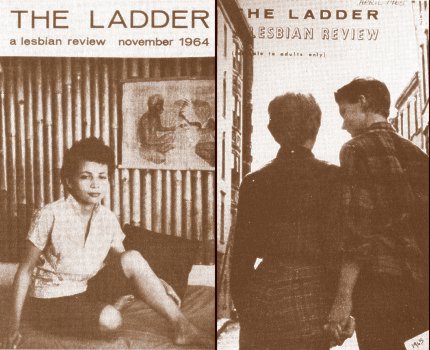

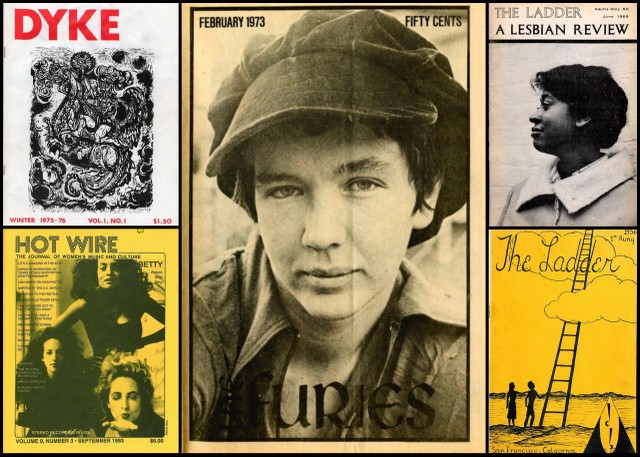

2. The Ladder (1956 – 1972)

“A typical issue would have one or two short stories (usually of the romance genre), an essay about “sexuality” by an expert (psychologist, minister, anthropologist), an historical biography about a famous or infamous woman who was probably a lesbian (or one who passed as a man), several book reviews by “Gene Damon” (Barbara Grier) or other contributors, news of homophile political and legal activities, poems, and letters from readers. “Cross Currents” was added in 1963; it began as “Here and There” and contained any information about lesbians, gay men, feminist actions, rumors of possible lesbians anywhere.”

(via Every Magazine Is New Until You’ve Read It)

The Daughters of Bilitis, founded by Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, debuted The Ladder in October of 1956. The first issue included reassurances from an attorney that lesbians had nothing to fear in joining DOB or subscribing to the magazine — at that time it was still very dangerous to be “out.” The DOB aimed to change the image of lesbians in society and the designation of homosexuality as a mental illness by presenting to the public a very sanitized group of “respectable” women: “advocating [to lesbians] a mode of behavior and dress acceptable to society.” They shunned butch/femme roles and had seemingly no awareness whatsoever of working-class lesbians.

The Ladder began as a 12-page newsletter of book reviews, news, poetry, short stories and DOB meetings news distributed to 175 friends and medical professionals who DOB thought would be interested in issues surrounding female homosexuality. The magazine was typed on a typewriter and copied via mimeograph. Legendarily, Lorraine Hansberry wrote the magazine in 1957 to inquire about buying back-issues and to say she was “glad as heck that you exist,” a 20-page letter that was published in its entirety in the magazine.

The Ladder, despite all its presently problematic aspects, made a huge impact on the community, many of whom knew little of others out there “like them” until they saw the magazine.

Historian Marcia Gallo: “For women who came across a copy in the early days, The Ladder was a lifeline. It was a means of expressing and sharing otherwise private thoughts and feelings, of connecting across miles and disparate daily lives, of breaking through isolation and fear.”

As DOB chapters sprung up in Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, The Ladder continued publishing, enabled by a $100,000 anonymous donation. Barbara Gittings became editor in 1963 and began publishing photos of actual women on the covers and gave the magazine a more political and lesbian-centric tone. Barbara Grier took over as editor in 1968, and in 1970 severed the magazine from DOB to publish it independently. There was a lot of drama surrounding this situation, which was all part of larger drama surrounding the movement and the DOB in general.

The Ladder published its last issue in August/September 1972. Grier would later note that “no woman ever made a dime for her work, and some … worked themselves into a state of mental and physical decline on behalf of the magazine.”

+

3. The Furies (1972-1973)

[read online at rainbow history]

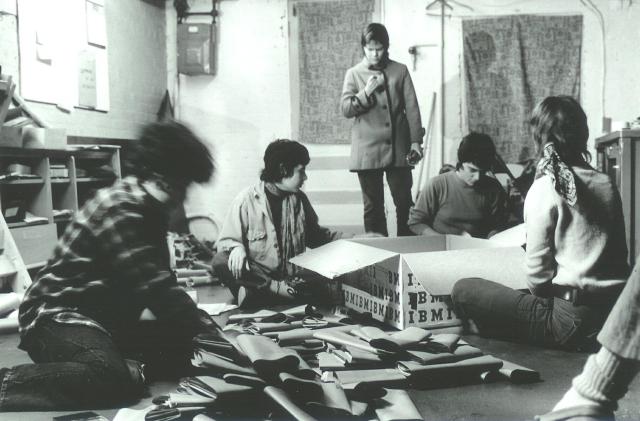

The Furies began as a collective, initiated by twelve women in D.C. — including Charlotte Bunch, Rita Mae Brown and Joan Biren — during the spring of 1971. They began distributing The Furies: Lesbian/Feminist Monthly in 1972, throwing their hats in the ring for the cause of “challenging existing patterns of living and behavior” and “providing an articulate ideology and challenging analysis of sexism, patriarchy, and the challenges facing lesbian feminists across the country.”

Furies office in basement of 221 llth St. SE, mailing out the newspaper, l. to rt. Ginny Berson, Susan Baker, Coletta Reid (standing), Rita Mae Brown, and Lee Schwing. ©JEB (Joan E. Biren) via Rainbowhistory.org

Bunch, when outlining the plan to initiate a women-lead revolution via newsletter, reminded her sisters to “have fun so we do not go mad in male supremacist, heterosexual Amerika.” In addition to herstory, political writing, social critique and anti-capitalist manifestos, The Furies published poetry by women like Pat Parker and Judy Grahn, photography by the aforementioned JEB and once even ran a piece by Gertrude Stein!

Historian Julie R. Enzer writes: “The women in the organization wanted to understand sexism and its internecine relationship with classism, racism, capitalism, and imperialism. They wanted to intervene in society to build a world that was different, a world that was based on a new set of values. The history of The Furies and the ways of thinking that they were committed to developing are useful models for people engaged in contemporary political—and poetical—struggles.”

You can find Charlotte Bunch’s article “lesbians in revolt,” from the first issue, all over the internet, a piece which laid a great deal of groundwork for the lesbian feminist movement.

+

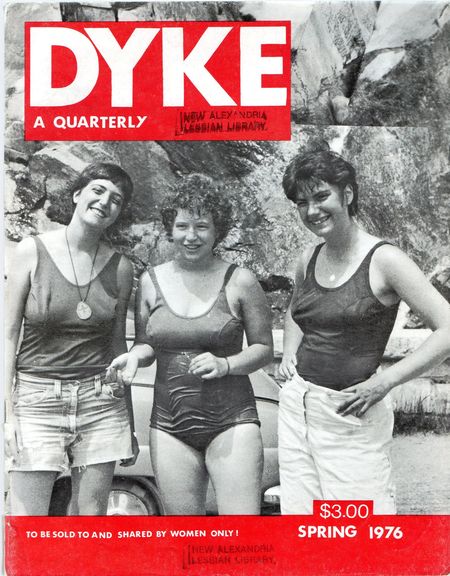

4. DYKE MAGAZINE (1976)

“We want to publish a magazine that fulfills our need for analysis, communication and news of Lesbian culture. We believe that “Lesbian culture” presumes a separatist analysis. If Lesbian culture is intermixed with straight culture, it is no longer Lesbian; it is heterosexual or heterosocial because energy and time are going to men. Lesbian community – Lesbian culture- means Lesbian only DYKE is a magazine for Dykes only! We will speak freely among ourselves. We are not interested in telling the straight world what we are doing. In fact, he hope they never even see the magazine. It is none of their business. If they chance to see it, we hope they will think it is mindless gobbledegook. We are already thinking in ways that are incomprehensible to them.”

In 1975, Liza Cowan and Penny House — best friends since the age of four — launched DYKE magazine. They were in their mid-twenties, living in New York, and wanted to be part of the burgeoning cultural conversation around lesbianism, and lesbian separatism in particular. Most lesbian separatists believed that the best way to live was completely without men altogether, and that women should band together and form their own self-nurturing communities free of ties to the patriarchal world. If you hate men, like me and Julie Goldman, then you probably think this is a pretty bang-up idea. Of course, it was more functional in theory than in practice and certain elements of the philosophy would be considered highly problematic — and often transphobic, racist or elitist — today.

The magazine made it through six issues before having to close, and now Liza and Penny have posted a great deal of DYKE’s archives online. Material included articles on “theoretical politics, live events, place, current and past history, media, fashions, music, home economics, literature, animal lore, health, applied sciences and gossip.” Basically, it’s like an amazing lesbian tumblr + livejournal, but in print and for the 70’s — which is why it’s so fascinating. The writing in DYKE is relatively personal and the writers are relatively inexperienced (their only “big name” is Alix Dobkin). You won’t find polemics from Audre Lourde or Adrienne Rich in DYKE, but you’ll find the closest thing you can to reading the diary of, basically, middle-class white lesbian separatists in the mid-70’s — complete with the angry lesbian commenters!

a letter to the editors of dyke magazine

+

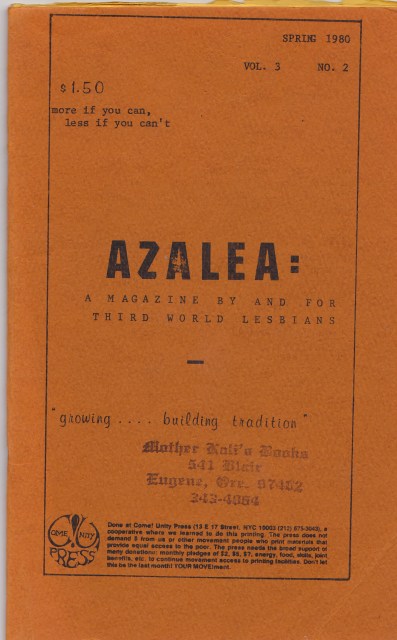

5. Azalea: A Magazine by Third World Lesbians (1977-1983)

“Now, in 1989, some of us (and the numbers continue to grow) are speaking of being lesbians — autonomously, collectively, emotionally, historically. Not only are Black lesbians writing, but we are writing – sharing – with other 3rd world lesbians as well… Native American, Asian, Latina and Black dykes are nourishing ourselves with ideas and feelings. Although there are many factors that keep us from each other – divert our energies – we are still able to do our own work. An enormous need exists for 3rd world lesbians to communicate among ourselves.”

Azalea was the hardest magazine to track down — I eventually managed to snag a copy of their Spring 1980 issue via eBay. I wanted to highlight at least one publication created by and for women of color (other titles include The Ethnic Woman, Black Woman’s Log, Triple Jeopardy, Achè, Sage, Malintzin Onyx Newsletter), but unfortunately was unable to find any you could read online.

Azalea was a product of The Salsa Soul Sisters/Third Word Wimmin Inc Collective, the oldest black lesbian organization in the country. It grew out of the Black Lesbian Caucus of the Gay Activist Alliance, officially splitting from the fathership in 1974 and inviting Latina women to join. “There was no other place for women of color to go and sit down and talk about what it means to be a black lesbian in America,” said original collective member Candice Boyce. SSS aimed to provide a political and social alternative to the discrimination and exploitation of people of color they experienced in lesbian bars.

Azalea’s editorial policy was unique — “we print what you send – work that is important to us as 3rd world lesbians. In order to keep the magazine non-elitist and non hierarchical, WE DO NOT EDIT YOUR WORK. Payment for sending your work is made in a copy of the issue containing your published work.”

The issue I have includes heaps of poetry, a short story called “The Mirror” about a woman whose co-worker is diagnosed with cancer, an article on the First Eastern Regional Conference of the National Black Feminist Organization and simple testimonies from women sharing the facts of their lives, like Lou Dublin, who in “I’m a Sister,” writes “Since age 20, i have lived my life exclusively with wimmin. As I consider my life being a mother, I realize that I too will need support from my sisters. So in return, I will give them my support, love and respect to all of my third world sisters.”

+

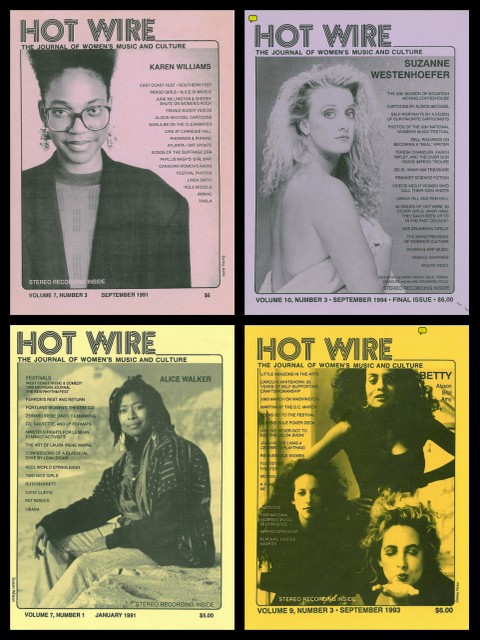

6. HOT WIRE

[entire HOT WIRE archives are online]

“HOT WIRE specializes in women-identified music and culture, primarily the performing arts, writing/publishing, and film/video. We strongly beleive in the power of the arts to affect social change, and we enjoy documenting the combination of “creativity” and “politics/philosophy.” We are by, for and about women: committed to covering female artists and women’s groups who prioritize feminist and/or lesbian content and ideals in their creative products/events.”

Described as “the essential publication to read during the 1980’s and 90’s” which “reported on and documented a movement and an era,” Chicago-based HOT WIRE launched in 1984 — their debut issue featured comedian Kate Clinton — and raged on for ten years under publisher/editor Toni Armstrong Jr., with subsequent cover stars like Alix Dobkin, Alice Walker, Alison Bechdel, Audre Lorde, Cris Williamson and Holly Near. Advisory Board Members and contributing writers, artists and photographers included Alison Bechdel, Joan E. Biren, Jewelle Gomez, Del Martin, Holly Near, Rhiannon, Amoja Three Rivers, Susan Sarandon, Barbara Grier and Phyllis Lyon.

Their front-of-book section HOTLINE was especially popular with its aim to “get women in touch with each other in spite of the dominant culture’s attempts to keep us isolated.” The multi-page section covered pretty much everything of interest to the readership — from announcing recipients of lesbian writers’ grants and prizes to providing info on how to help a lesbian couple whose house recently burned down to the scoop on political and social actions, bookstore openings, publications, films, and local meet-up groups for various special interests. The January 1992 issue includes news on the Madonna fanclub, the Montreal World Film Festival, The Lesbian Herstory Archives fundraising, a trivia contest, Thelma & Louise, same-sex partner immigration in New Zealand, Lily Tomlin, The Women’s Motorcycle Festival and an auction of Frida Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait with Loose Hair,” among many other things.

When Toni Armstrong launched the magazine, she committed to producing it for no less than ten years, and when those ten years were up she made the tough decision to close the publication — citing a need for time, money and sleep and also her “acceptance of the fact that we’re nearing the end of an era.”

Despite the fact that these projects are rarely profitable and usually fold within the first five years, lesbians seem uniquely enthusiastic about using the magazine format to build community, against all odds. For decades we’ve been pouring heaps of time, energy, emotional space and money into assembling and distributing our own words and stories on our own terms. It’s a tradition we hope to be a part of and we owe so much to the women who made these magazines and are blessed to have so many archived publications online.

Books referenced to write this post include: Happy Endings: Lesbian Writers Talk About Their Lives And Work, by Kate Brandt, and Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America (Between Men–Between Women), by Lillian Faderman.