The first time I saw Basic Instinct was at a party. Was it New Year’s Eve? Was I 27? I think so. Let’s say the answer is yes. My friends and I had this bit where we’d put dystopian movies from the 80s or “erotic thrillers” from the 90s on in the background when we hung out; we were big on irony. We’d get high and fall asleep on the couch and wake up hazily to Eyes Wide Shut; come back from getting another beer and find someone in latex climbing into a helicopter in Demonlover. It was in this spirit we put on Basic Instinct, a movie I had somehow managed to know nothing about other than the cultural fact of Sharon Stone uncrossing her legs.

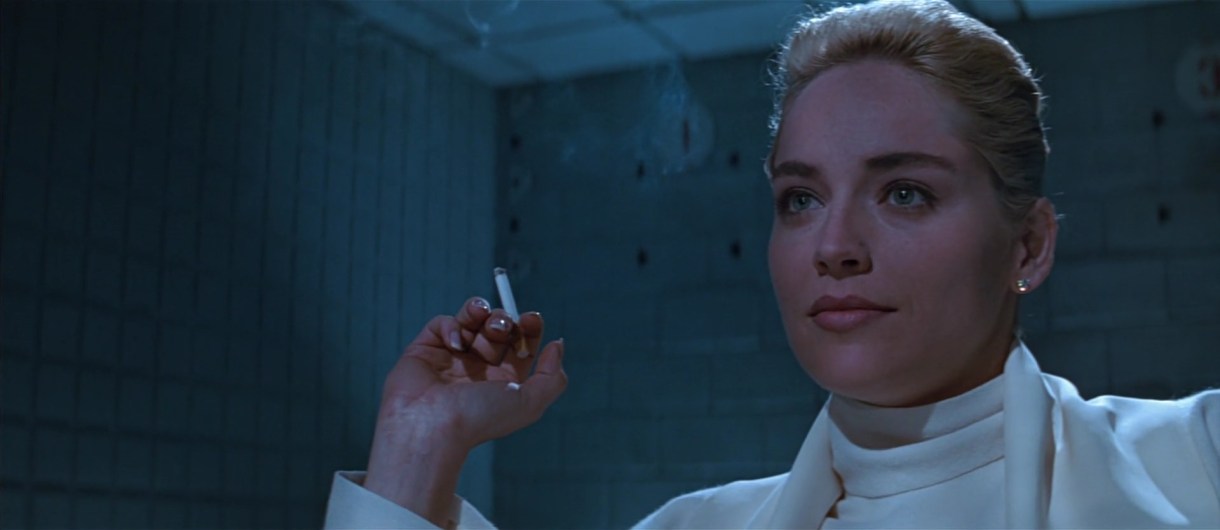

The friends I was with that night were all straight, bless their hearts. As the movie progressed, they started to give me the looks you give your girlfriend in the middle of family Christmas dinner. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m so embarrassed. And also: you know I’m not like that, right? You know I’m different? We’re still good? They would have turned it off if I had asked; they’re good people. They are different, mostly. I didn’t ask. Instead I watched her zip up her white dress in the mirror; I watched her cross and uncross her legs; I watched her, and my friends watched her, and in the movie we were watching the other characters, men and women, watched her. I hated her so much, and so purely, with such satisfaction. I couldn’t look away.

Basic Instinct came out in 1992, when I was four years old. Catherine Tramell, played by a lithe and leonine Sharon Stone, is a bisexual crime novelist suspected of the murder of her rock star boyfriend. Nick Curran (Michael Douglas) wants to prove that she did it, and also fuck her. Does he care more that she’s a murderer or more about fucking her? Does it matter? Isn’t that always the question. The top tags for the movie on IMDB are “manipulation,” “mind game,” “kissing,” “female star appears nude,” and “strong female lead.”

Catherine’s girlfriend is not featured on the VHS packaging or really anywhere except one very posed and very sultry screencap on IMDB. Her name is Roxy, which I felt was about right. Roxy does not survive to see the end of the movie. My friends got high and drank PBRs and put different items in the apartment on the dog’s head like tiny hats. I watched the movie. At some point — I’m not sure whether it was when Catherine and Nick are reflected fucking in Catherine’s ceiling mirror, or when Roxy’s car flips over dramatically in the middle of the night, or when Nick’s brunette love interest is sprinting virtuously down a dark hallway — my friend M turned to me, a little apologetic. “This is like, really bad,” he said, or something like it. I think he meant something like is this bothering you? Are you okay? It did and I wasn’t and also I didn’t want to stop watching; I hated her and I hated me and it felt good to do it. Sharon Stone crossed her legs, reached for an ice pick, nothing but sex and death behind her eyes. And suddenly I could scratch a particular itch that I hadn’t been able to reach any other way, something unhealthy and also soothing in a way I couldn’t articulate.

The thing about Basic Instinct is that it’s very bad. It’s not just bad representation, it’s a stupid movie, as erotic thrillers from 1992 are wont to be. Why does Catherine write under a pen name and then put a 3×5 inch photo of her face on the jacket anyway? Why the intense revulsion at wearing underwear and using ice cube trays? How is it possible to have that many friends who are convicted murderers? Why does a tense conversation between Nick and Gus happen in the middle of a crowded country bar that we never return to and has nothing to do with the rest of the film? It’s so bad in some places it’s funny actually — Nick snarling “it was the fuck of the century” to a bored and amused Catherine after some truly, deeply run-of-the-mill sex is actually incredibly funny. And although it’s one of the worst portrayals of bisexual women imaginable — sociopathic, hypersexual, lying and manipulative — I think I could have found a way to find that funny too if M wasn’t watching me watch it, if I wasn’t in a room full of kind, well-intentioned straight people watching me watch it. I knew my friends didn’t think I was a narcissistic psycho; I knew they weren’t repulsed or horrified by me. But as Catherine and Roxy gyrated bizarrely in a tacky 90s nightclub could feel their secondhand embarrassment for me — something close to pity, letting me feel something close to shame. It was a feeling I hadn’t put a name to yet, and that night I could feel it solidify in my chest with a weight that was somehow comforting.

Before my first time seeing Basic Instinct was my first time at a Midwestern gay bar. Back home, on the East Coast, we didn’t have gay bars per se, or at least not lesbian bars. Gay men had some leather bars and we had Second Saturday at Machine, scheduled dyke nights across the city you had to keep track of on a calendar, and queer karaoke with Jack and Cokes on Thursdays. But in Indiana, paradoxical to my coastal elite experience, you could visit an institution that had obviously been a sports bar in a previous life but was now wholly dedicated to serving weak drinks at small tables inside a dim wood-paneled room with a small stage for drag shows. My memory of it is that first view, dark and cluttered and mostly deserted, as I walked in with the natural foods store employee I was sleeping with. She had beautiful dark hair and liked to tell me about the biodynamic energy in the carrots she sold. I could never be sure whether she was kidding about that or not. I was nervous about being there — I think we both were, and I wonder now if she had never gone to that bar even though she had grown up there, if she needed someone like me to buy her a drink and put a hand on her leg during a drag king performance of “Pony.” I don’t know what either of us needed, honestly.

There was a group of straight people in the bar that night — inasmuch as you can perceive without asking somebody whether they are “straight” or “not” or “at a gay bar to celebrate a birthday because it seems like a novel thing to do,” they were a group of middle-aged straight people at a gay bar for somebody’s birthday, presumably because it was a novel thing to do. We watched them giggle and nudge each other in the ribs, and we drank our overpriced Indiana drinks, and we all listened to the drag queen on stage lip sync “How Many Licks.” I had been to plenty of straight bars with girls before, heard all the things sneering men say when you’re too drunk to remember you shouldn’t kiss her like that while you’re still out in public, the looks straight people give you as she lights your cigarette out on the sidewalk. The straight people had never followed me before, though, to my own space — and this was ostensibly my own space, right? In some way? I was kissing her in the back of the bar, her white white teeth in the dark tasting like vodka cranberry, the drag queen on stage lip syncing designer pussy, my shit come in flavors in the middle of this tired little bar that was like the experience of drinking warm beer underneath a pool table, and she was all I could see in the infantile disco ball light — but not through my own eyes, not really, more theirs.

I don’t know for sure if they were watching us, but I know that we were part of what they came there to watch on a fundamental level — as I have been so often, in my role as a girl kissing a girl in a dark corner of a bar. Set dressing, something titillating for the sake of ambiance. I don’t remember anything about how I felt that night, not really. I don’t remember leaving, not because I was drunk but because I think I floated away quietly at some point that night, flitted off to the wet asphalt of the empty parking lot with my fingers still tangled in my date’s. I had a body worthy of spectacle when it was next to another particular kind of body, as well as shame and hatred but nowhere to rest it, nowhere to put it down, and so instead I disappeared. I felt overexposed, but more than just me — something about the sweet sadness of the rundown bar was special to us queer patrons, or could have been. But seeing it as a straight birthday party it felt tacky, worthy of pity.

We left the bar and later I would leave that girl too, tell her at 4 am I couldn’t stay over because I had somewhere to be in the morning even though it was a Saturday and the lie was obvious. It wasn’t because I minded so much falling asleep next to her but because she lived with her parents and because the idea of them seeing me so clearly in the light of a Saturday morning felt unbearable. I guess I was worried they would see something true, something I was trying to avoid seeing in myself.

I was new to the Midwest then, and I didn’t know how much to worry about being seen, especially with her. I remember walking with an arm around her on a nighttime sidewalk, snowflakes spiraling through the streetlight glow in a way that was somehow particularly Midwestern, and feeling a low note of panic — was this the kind of thing people noticed here? If so, what did they think? She had grown up here and she didn’t seem nervous, so I followed her lead. Later on she held my hand in a bar that had enough people in it to obviously notice us, and also spectacularly bad service. The bartender realized this and, apologetic, slid us two complimentary drinks: white gummi bear shots, sickly sour-sweet. I knew instantly that we had flown under the radar; somehow nothing signaled perceived straightness as much as being offered a gummi bear shot. I felt relieved and insulted at the same time. We both took our shots before we left.

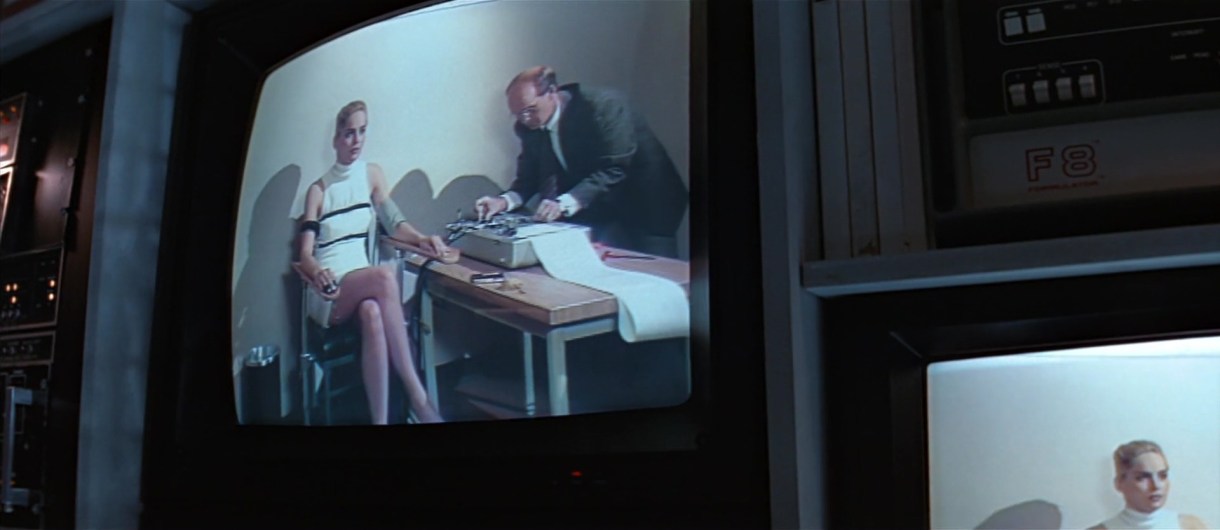

Catherine Tramell is never not being watched. She knows this, and seems to revel in it, even. When she realizes the door is cracked open as she gets dressed she slows down, takes her time, enjoys it. Catherine is, literally and figuratively, the suspect in the interrogation room who knows who’s watching her from behind the one-way mirror. There is an implication, I think, that this is part of what is supposed to be off-putting about her. It is more believable that this woman might have murdered her boyfriend in cold blood because she is the kind of person who, when she feels men’s eyes on her, becomes more comfortable and controlled rather than less. I don’t say this to point out some kind of ironically feminist element, subverting the gaze or whatever you want to call it. It was because of this that I hated her so much, at least in part, not in spite of it. She grins as she crosses and uncrosses her legs in that fucking white dress, smiling wolflike into the interrogation room camera lens that she knows transmits to men who are staring at her. The irony of the fact that, in real life, Sharon Stone didn’t know the cameras could see her exposed genitals in that one famous shot is not lost on me.

Catherine loves being watched which is great because Roxy loves watching! We see Roxy before Catherine; in a weird moment of slippage, the cops first assume she is Catherine, probably because she’s hanging out alone in her house. There are a few moments later in the film where it’s almost possible to mix them up anyway; they’re both blonde in an intensely 90s way and love staring dramatically from across a room. Roxy is always staring, always watching. She watches Nick watching her with Catherine, she watches Catherine dance away from her and into Nick’s arms; according to Catherine, Roxy watches her fuck the parade of annoying dudes she takes to her bedroom with the mirrored ceiling. According to Catherine, Roxy likes this; Roxy does not behave particularly like she does. “She wanted to watch me all the time,” Catherine says. It is not made clear why this would be enjoyable for Roxy specifically, whether it’s something that brings particular pleasure to Catherine either. The movie seems to consider this point so obvious it requires no explanation; who doesn’t want to watch? Eventually Roxy watches Nick from inside her car before trying to run him over and kill him, arguably the most realistic character decision of the film.

The first time I remember being aware of a man watching me, really watching me, I was fifteen. I was taking the commuter rail into Boston’s South Station, slumped sullenly into the squeaky vinyl seat like the teenager I very clearly was. The tall, thin man with the briefcase and suit across the aisle didn’t care; he glanced over at me the whole ride, long wide-open looks that he didn’t bother to make furtive. As I realized this I looked over at him, surprised, and accidentally met his eyes. He didn’t look away. After the train reached the station, he became the first man to follow me in public. “Where are you going?” When I told my mother about it later, and how I had unintentionally made eye contact, she said “You have to be more careful.” I was mad at that, but also, she was right.

For all that we get to watch her every move — through the camera lens, through other characters’ eyes, through the plentiful mirrors scattered throughout the film — so much about Catherine remains unclear, impossible to read. Why did she murder her boyfriend? Why does she get so fixated on Nick, who is obviously and objectively a scary and violent person? What does she want, exactly, that motivates her to become a full-time sex kitten homicidal maniac? Why does she do any of the things she does? What does she do when no one’s looking? What kind of person do the sum of her choices add up to? We’ll never know, because bisexual murder nymphos from 90s erotic thrillers aren’t designed to make sense. They are points so obvious they don’t require explanation. They’re designed to be thrilling, in every sense of the word. What a thrill!

In graduate school I took a class in narratology, the only school of theory I ever really liked, because it was kind of like watching How It’s Made for stories. Or maybe because it was someone finally admitting that stories are, in fact, made; consciously created by real humans who are flawed and have their own stupid preoccupations and were sometimes hungover. Narrative theory says, in part, that narratives have layers to them: the characters interact with each other; the narrator or lens of the story itself communicates with the conceptualized audience, the idea of a consumer; and bracketing all of it, the actual person or persons who made the story are saying something to the actual person or persons who are taking it in. I used to draw diagrams of this in class: neat brackets that read “implied narrator, implied reader,” and so on. There’s Nick looking at Catherine, and Catherine watching him watch her, a room full of male cops watching them watch each other. There’s the camera lens watching both of them, the screen upon which it’s later projected. There’s the glassy-eyed people I imagine were on set and behind the camera in 1992, and me watching from M’s couch with a warm beer in my hand, tired eyes and tangled hair, a few hours away from the ball drop and stoned laughter and falling asleep on an air mattress. I am, in this framework, at the “level of nonfictional communication” as my friends pass me a drink and check how long til midnight and the dog makes a strange high whining noise from the corner.

Of course, this theoretical model can’t account for how messy it really gets. It is successful, maybe, in describing one singular narrative; it doesn’t illustrate how there are dozens of them and they build on one another, layer over and dovetail with and derail each other. How that man followed me off a train one day but how later, a year or so on, I walked back onto the same one with a girl out of the pouring rain, both of us soaked to the skin and shivering all the way home. It doesn’t explain the two drunk men who leaned down to leer one night in the theater district while I was kissing someone — I can’t even remember her name really — on the curb outside the straight bar, how they stared and hissed. The straight people in that Indiana gay bar watching me and my date while I watched the drag queen looking like the Virgin Mary in brown lipliner and pure white spotlight mouthing stop look and listen get back to your position. M watching me watch the TV screen in his Chicago garden apartment while I watched Sharon Stone reach for an ice pick on the floor and pretended this could be fun for me. The way I watched a 100-lb girl I had just met that night drink a bottle of red wine by herself in 20 minutes, and put an arm around her stumbling little body; the way he watched me do it and yelled later I saw you with her, I saw you, like I had loved her rather than just wanted to keep a girl, any girl, from harm. That photo I still have of the first girl I loved tangled in blankets, looking up into the camera lens and at me aiming it like she loved me too, like there was nothing and no one else she wanted to be looking at. The look from across the crowded room, his eyes on mine in the dark when everyone else was watching the stage and how I could hear a pin drop inside my ribcage. How my husband asked once don’t you worry about people seeing you with me and thinking the wrong thing?, how I didn’t know how to say everything they could think is the wrong thing, anything they see they would misunderstand. How the therapist looked at me, sincere and kind, when she said Maybe you’ll just never be able to have healthy relationships with men. You know, because of your father. How I look to myself in the bathroom mirror in the middle of the night, the aggressively yellow cast of the godawful track lighting I hate, how it feels like I’m never alone even then.

Catherine Tramell is never alone, never outside a line of sight. Nick’s view is our view; we only see of her what he looks at. She only exists because she’s looked at, because you can’t be thrilled by something that isn’t in your field of vision. I understand, obviously, that she was never conceived to be a fully realized person or even character, that that was what created such an easy and convenient void for me to place my loathing of her and of me. But I still thought that maybe the problem was her audience; science tells us that when we view something, even as minute as a single atom flung through space, we are in some way affecting it, informing its trajectory. She could be a real person if she could do it in private, without the weight of other people watching. And that by some transitive property I couldn’t understand, I thought this could be true for me too, maybe. I thought that if I could be alone, outside of anyone’s view at all, I would have a chance to finally figure out what I actually meant; that I could relax and just be rather than be constructed. That was my problem: I needed to be viewed less, to be flung through space without witnesses. I wanted freedom from narrative, which requires inherently a narratee.

This summer, I got on a plane with one carry-on and came back to my teenage bedroom in my mother’s house, leaving behind my husband and partner of many years and the life we had cobbled together for ourselves. By the time I did I had already felt like a bad movie character for a long time, and whoever was doing the role was pretty clearly phoning it in. I wanted to be alone; to be somewhere isolated and by myself. My mother’s place is in the kind of area where it’s almost too eerily quiet to fall asleep at night; you can change with the window open because there’s no one around to even see. I thought that by doing this a sense of self would materialize for me; that I had a fully realized character that other people’s ideas of me had just been obscuring. This was a fantasy I had for a long time, maybe longer than even I really know. I was quietly shocked to realize that the self I had hoped was silently developing without my having to tend to it, like a sweet potato left in the back of the pantry, seemed not to be there. It felt like nothing was, really. Sometimes the parts of ourselves we ignore don’t just grow fallow and untamed in our absence; they turn inward, crack concave, become a void. And you just have to sit there in it, waiting for something to materialize, waiting to be able to see yourself in that anemic early morning light for as long as it takes to make out the faint outlines of your self against the dimly lit past.

Rachel, this moved me more than I can say. Like your essay on Salem, this is one I will bookmark and revisit again and again for different and the same reasons every time.

Rachel you are just and this is just so very very good.

It’s almost like, you are too good

This is beautiful. It makes me remember now the difficult confusion and fascination I had watching this movie when it first came out, when I was 17, when there were not other better portrayals of any kind of queerness anywhere to be found in small town PA, when I had never met another queer woman, when the internet basically did not exist. Wow, it’s a lot to think about.

Rachel thank you. Through your writing and activism you give me direction, even if you’re sometimes unsure of yours.

thank you so much

Thank you for this, I’ve been fantasizing a lot recently about running away and living on my own in the middle of nowhere so I can just be, and you really articulated that for me:

‘I thought that if I could be alone, outside of anyone’s view at all, I would have a chance to finally figure out what I actually meant; that I could relax and just be rather than be constructed. That was my problem: I needed to be viewed less, to be flung through space without witnesses. I wanted freedom from narrative, which requires inherently a narratee.’

i watched this last night with our esteemed design director sarah sarwar so that we could both be prepared for the inevitable excellence of this essay and you’re right, it’s much easier to watch with another queer person so that you can make fun of it together, it would be so weird to watch with the straights.

i love you and this is one of my favorite essays we’ve ever published. i have so many feelings about it i am still processing!

I am in complete and utter awe, Rachel. Thank you for this. It’s the best essay I’ve read in YEARS and it DESERVES AWARDS??? Not to be dramatic but I actually had to lie down on the floor after reading.

same

Wow. I will never cease to be amazed at how Rachel can loop so many threads into one fully glorious piece

Rachel, I love you. And also thank you.

Wow. I did not expect to end up with so many feelings when I clicked on this article.

just gonna sit here and take it all in a thousand more times <3

Oh Rachel <3

Rachel, your writings touch my heart.

Rachel <3

powerful

Thank you <3

Thank you, that was beautiful.

rachel, this is wonderful. i’ve never seen this movie, but in the one film class i took – queer cinema – this topic was my favorite as well. we talked a lot about lenses and layers of perception in brokeback mountain, and then i went on to apply it to every other film we watched. it’s especially interesting to apply to queer stories as a queer viewer, and i wrote about it a bit in terms of thinking i was straight the first time i watched brokeback vs rewatching it for class while consciously queer. but i never thought to fully apply it to personal narrative the way you have here, and it’s fascinating how you’ve brought the two together and applied the concept to your own story and how you think about yourself – it’s something that i’ve definitely always done too, but never really realized, or thought to connect it to how i analyze fiction.

ANYWAY. this is really great, and really smart, and i loved reading it. i feel like i learned about myself and how i think and tied a bunch of things already in my head together because of it, so thank you.

i missed your writing so much, this was so powerful. you’re so insanely talented.

“I had a body worthy of spectacle when it was next to another particular kind of body”

…<3

jesus christ rachel

This is beautiful, your writing is lovely, and it just slipped into all the cracks in my heart.

wow

this is extraordinary. thank you for writing.

Wow. This is beautiful and powerful. Thank you. There will definitely be rereading and processing.

And I can’t get this line out of my head now because it’s hitting hard:

“Sometimes the parts of ourselves we ignore don’t just grow fallow and untamed in our absence; they turn inward, crack concave, become a void.”

HOLY FUCK RACHEL

This is freakishly good writing. Also, I live in Indiana, and the Midwestern stuff rings painfully true. Thank you so much for this.

Okay, I have to comment again. This is destroying me in the best way possible.

Everytime you write a long read personal essay, I read it all up, and then just crumple

And then I send it to my friends so they can do the same

The concept of existence outside of others looking at me is one I’ve thought on for years without words to describe it. It is a concept that exists within me in such deep and dark places that it feels like it is just a part of me. Thank you for doing such an eloquent job of describing it.

This was beautiful.

i have read this now for the seventh time and i can’t tell you how much and on how many levels this resonates with me, rachel

after spending some time with your words i’m gonna send this out to some people i know.. in the hopes of them finding and seeing a part of me that is hard to explain but feels so obvious in your words.

thank you so much for sharing this.

<3

*lies down on the floor*

I think I need to go to the hospital, this hit too hard

I’ve read this piece at least eight times now and each time, it stuns me a little more.

I feel like I should say something more profound to repay you for the depth of this prose…

…but it really just renders me speechless.

This was amazing, Rachel. Thank you.

This is unbelievably good and articulates something that I’ve only ever felt but have never been able to communicate. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

While the circumstances are different, having moved back into my parent’s home with my child after ending a marriage, I went from having time to myself, private and unseen, to being seen and analyzed constantly. And I’ve provided them a myriad of ways to analyze me: as a parent, as a divorcee, as someone who my family had always seen as straight, now publicly out, with all the adjustments their minds had to make, as a single parent struggling to secure stable employment. Any sense of privacy has been completely erased and I’ve had to accept being on display in my huge family.

I recently pitched a very silly and severely less eloquent underdog icon list because under the weight of my circumstances, I will be crushed if I don’t create my own levity.

Anyway, your story was so beautiful and powerful. l will definitely need spend my day pinballing deliveries around the city to process everything you said.

This is so good, Rachel. It’s funny, I’ve never seen this movie, it was on my radar, and 90’s movies with any hint of queerness were definitely my thing, maybe I’m glad I never watched it. This line really got me, “And suddenly I could scratch a particular itch that I hadn’t been able to reach any other way, something unhealthy and also soothing in a way I couldn’t articulate.” Also this, “What does she want, exactly, that motivates her to become a full-time sex kitten homicidal maniac?”

♥

One of the best essays I have read and certainly a favorite from AS. Thank you for sharing this Rachel. Know you are held by more people than you know as you continue this journey.

This was really wonderful

Wow

Rachel you are so talented

co-sign

Great piece! Thanks for writing and posting.

Rachel <3

Rachel,I love what you write and the thoughts you think.