Searching for My Own Queerness in Bollywood

Between my parents’ house in LA and my apartment in NYC, I have a collection of at least 50 Bollywood film posters buried in my closets (pun intended). I still have heavy, glass-framed posters of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, classic romance-drama films of the 90s, hanging in my childhood bedroom. My obsession with Bollywood goes as far back as I can remember (and then probably before that, too.)

Looking back, I chalk up this obsession to a plight that plagues me more and more as an adult — the unquenchable thirst of wanting to see someone like me on television, in movie theaters, and on the pages of novels that line my bookshelves. When I was younger, this meant I wanted to see a South Asian woman who found love and acceptance against all odds. Later, as a young adult coming out as queer, this meant yearning for so much more: love and acceptance, sure, but also validation of both my desires as related to people of all genders and my choice to don short hair and wear men’s clothes.

All of which is to say: I needed to know it was possible to be a South Asian queer woman who could find love and have a “happy” ending.

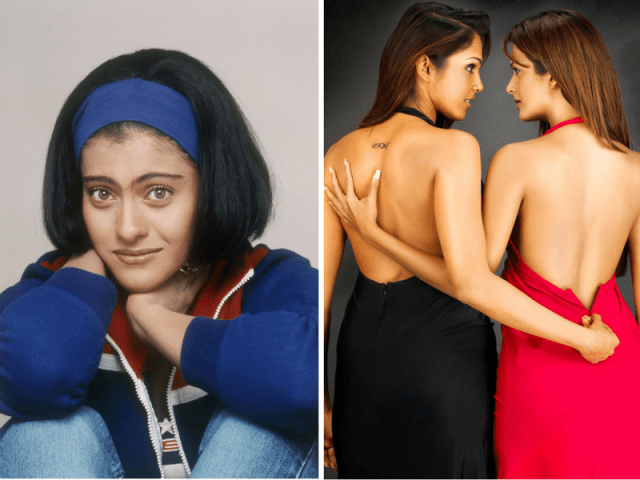

Left: Kajol as tomboyish Anjali in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, Right: Isha Koppikar and Amrita Arora in Girlfriend

What I learned from this cinematic medium that taught me to be fluent in Hindi just about the same time I learned English was that someday, against all odds, my knight in shining armor would win the approval of my family and marry me in a multi-day, multi-event big, fat, Indian wedding. As I grew into my intersectional identities, I thought my queerness meant this would all vanish, that somehow my Bollywood ties to my parents’ roots would be severed by the deviance of my desires. Instead, part of accepting my identity as both queer and South Asian has meant revisiting Bollywood in search of female presences that both entice and inspire me. Unfortunately, Bollywood has left much to be desired in this regard.

In the ’90s, Hindi cinema began to scratch the surface of LGBTQ depiction with caricature-like portrayals of gay male characters who were effeminate (and therefore “less” than the cis-hetero men who sidelined them) and/or hypersexual (striking fear in those around him that they would fall prey to his frivolous ways). These gay men were, therefore, misfits who became the butt of all jokes. From roles as the only one in a group of friends who’s worse at sports than his “manlier” friend (like in Pyaar Kiya Toh Darna Kya), to design-privy fashion icons (as in Fashion), and single, older, hypersexual males like Boman Irani in Dostana and Rishi Kapoor in Student of the Year, Bollywood depictions have made gay men the epitome of stereotypes. Through it all, these characters most often never openly identify as gay, nor are they portrayed with any other layer of identity (or humanity).

Despite India’s own troubled past with the criminalization of same-sex relations (first de-criminalizing and then re-criminalizing colonial-era Section 377) these terrible depictions easily became Bollywood’s flag of visibility for a community that not only has more depth in individual identities but that span more identities than just cis gay men.

On my own journey, I discovered many loves, in the forms of both female characters I resonated with, as well as those whom I wanted to emulate.

The first of these was Kajol, star of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai and countless other classic romance-dramas of the ’90s. In KKHH in particular, Kajol portrays Anjali (second only to Rahul as the most overused name in Bollywood), a tomboy-ish short-haired woman who loves basketball and is, essentially “one of the guys.” This trope plagues her when she falls for her best friend Rahul, when he is instead in love with Tina, the short dress-wearing, beautiful girl on campus. Anjali even goes so far as to try wearing makeup and dresses to fit in with girls like Tina, but is mocked endlessly. I related much to Anjali, basketball to non-girly clothes — so much so that for a period of time, I thought I too could blossom into a more femme (and therefore more desirable) woman eight years after college and finally end up with my first love.

Later came Fire, a film I discovered years after its release. The two female leads find love with one another after differences and abuse from their husbands (who are siblings). Though groundbreaking in its depiction of love between two women, which I found immense resonance with, it was also a story that showed this love as the byproduct of misogyny and failed straight relationships. This wasn’t my story, and though its desire lit a fire in me, it wasn’t something I could look up to, or even point to within my community as a means of understanding my lifestyle.

Angry Indian Goddesses

Then came Girlfriend, a film that was open about its lesbian angle. In it, a love triangle develops between two female friends, Tanya and Sapna, and Sapna’s boyfriend. Tanya is shown as jealous and overprotective of Sapna, to the point of obsession and violence. Eventually, her psychosis marks her end, showing me, and lady-loving Indian girls like me that lesbians were literally crazy.

Bollywood has since moved the needle, albeit a little bit. First, there is a subjective understanding of feminism being a concept, and the mainstream success of films like Queen show this. Showing the self-reflective journey of a woman whose marriage falls through, Kangna Ranaut displays the kind of independence that I strive to embody by being as out (and unreliant on men) as I am.

There have also been progressions with male gay depictions, with strong, multi-faceted characters in Kapoor and Sons and Aligarh. Where the first dealt with a gay man’s very real and internalized struggle about coming out to his family, the second showed the true story of a gay professor in the city of Aligarh who was outed and ostracized thereafter. Both depict these characters as people with more to them than just their same-gender attractions, eliciting relatable humanistic struggles around conformity, and the privilege (and burden) of being out.

And finally, in 2015, the movie Angry Indian Goddesses was as close as ten-year-old me could’ve gotten on the journey of self-acceptance. Upon the premise of reuniting for a bachelorette party, seven women gather in Mumbai and find out that two of them, Freida and Nargis, are the ones getting married. The movie touches upon issues of gender equality and the treatment of women in a patriarchal society, while also weaving strong female characters, the importance of female bonding, and a female-female relationship that is treated with dignity and grace. In the end, this relationship is not what defines either the movie or its characters —and though neither had hair as short as mine, I reveled in the completeness and relatableness of both the women-loving female characters and the straight ones.

Priya and her partner in Central Park, NYC (Photo Credit: Grishma Patel)

I don’t put up as many Bollywood posters on my wall as I used to; my apartment walls instead adorned with pictures of my partner and I as well as her acrylic paintings of everything from landscapes to peacocks to beautiful women. My life now consists of creating and capturing real life narratives forward for young Indian girls like me who still seek holistic portrayals of queer South Asian women. I believe that for my family and friends, the simple act of being out is resistance in and of itself.