Ever since I started writing about anime for Autostraddle, Revolutionary Girl Utena has been one of the most requested anime for me to review or discuss. At first, I assumed it was just because it was a popular, mainstream anime series with some yuri (lesbian) themes, as the main two female characters appear to be in love with each other. But then, as I looked more into it, I found out that — at least in the series itself — the two girls never actually get together or explicitly admit their feelings. Okay, so why do lesbians who love anime love Revolutionary Girl Utena so much? I had to find out.

When I watched it myself, it immediately became apparent to me why this show has so much to offer transgressive and queer women – not just women who love other women, but women who defy society’s rules about gender and sexuality in any way. Many fans of Utena are quick to point out that the show should not be reduced to just being about the relationship between Utena Tenjou and Anthy Himemiya, and in a way, they’re right: but not because Utena isn’t queer. It’s because everything about this series is queer.

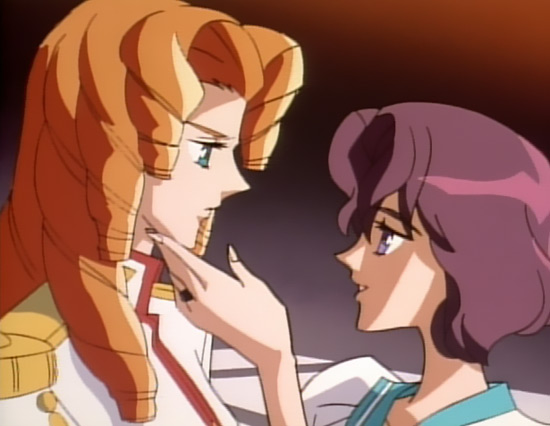

For a quick plot summary: Utena Tenjou is a junior high student at the mysterious Ohtori Academy, where students compete in duels in order to win the hand of Anthy Himemiya, the “Rose Bride.” Why do they do it? No one really knows (and they won’t until the end of the series), but students can only participate as Duelists if they are a part of the Student Council, who wear rose rings to signify their membership. That is, until Utena comes along, who has her own rose ring that she received from a prince long ago, who saved her and promised that the ring would lead her back to him one day. Instead of being a princess, Utena has decided she wants to become a prince herself, and dresses in boys’ clothes and focuses on saving people.

This is how she gets drawn into the Dueling system at Ohtori. Her friend Wakaba is publicly insulted when a boy she likes rejects her; said boy happens to be Saionji, the current Dueling champion and ruler of Anthy, who is forced to do whatever her fiancé(e) commands as long as she is engaged to them. Saionji challenges Utena to a duel, which she wins – making her Anthy’s current “master,” although Utena is bothered by her obedience (which is also far more complicated than it seems). The other Duelists begin challenging Utena for her title and Anthy’s hand, dictated by vague letters from someone calling themselves “End of the World” – and Utena’s life gets considerably more complicated.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J3e2GwpZ7ug

The series defies gender roles at every turn — and much of that has to do with the heroine, Utena Tenjou, herself. Growing up during the “Disney Renaissance,” I always felt like I was the rare girl who didn’t want to be a princess. I didn’t want to be saved by some boy; I wanted power and influence for myself. I wanted to do the saving. Utena does a lot to play with the common tropes of fairy tales, including what makes a “prince” vs. a “princess.” Utena is a princess who wants to be a prince, who dresses like a boy and is better at solving problems with her sword than with emotional manipulation, who wants to save people as a prince rather than “be saved” as a princess. She is every bit the heroine I wish I had as a youngster who was far from the girliest girl on the playground, and reminds me of why it was characters like Mulan — not only powerful and capable, but also, at-odds with traditional femininity — who resonated the most with me.

The “weaponized femininity” of the magical girl genre is something that gets a lot of credit in anime feminist circles; I also have written about how important Sailor Moon was to me as a young feminist. But the truth is, the world we live in is one that overwhelmingly favors so-called masculine qualities like assertiveness and leadership, where fights are won with a sword or a gun rather than a magical rainbow wand or the power of dance. And even without society’s expectations, some girls are going to possess masculine qualities. As a woman on the autism spectrum, society’s emphasis on “feminine traits” is alienating to me, because my brain chemistry means I’ll never be traditionally feminine in behavior anyway. I’ll never be someone who is naturally good at reading people and at being nurturing. I’ll always be better at constructing a good argument than “killing with kindness.” And the fact of the matter is that, while having some masculine personality traits can get women to the top in privileged fields like the business world or academia, overall, women are still not allowed to truly defy their gender roles. (Heck, even Utena herself, while being masculine in personality and goals, is still traditionally feminine in appearance other than her choice to wear the boy’s uniform. She has long, pink hair and she is conventionally attractive.)

That’s why I wish Utena had come to me when I was younger, still unsure of my sexuality and unsure of how much I could embrace my more masculine qualities in a society that was continually telling me I had to be more feminine not only to be attractive to boys, but to be valuable at all. Even the nerdy awkward girl characters I loved in media rarely stayed that way for long, eventually becoming more socially-adept and “normal” and finding a guy to love them. Utena, however, stays awkward and masculine throughout the series; she’s still inexplicably popular and adored by the student body in spite of this, though it’s mainly the female student body in her case. The guys, especially her dueling opponents like Touga and Saionji, are initially threatened by her and don’t know what to make of her. Even if their opinions eventually change, the guys still desire to mold her into something more socially acceptable and easier for them to control.

That being said, I should note that it’s doing the male characters of Utena a disservice to dismiss them as mere straw misogynists; Touga in particular is incredibly complicated in his own special way, and one of my personal favorite characters in the series. Every single duelist has their own struggle to overcome that is tied into growing-up, family and sexuality, probably the three main themes in a series that is overflowing with them. This is part of why the plodding, episodic exposition of the “Student Council” arc (the first 13 episodes of the series) makes perfect sense once you’ve watched the entire show, because in fact, you do need that much set-up to understand these rich, multi-faceted characters and what exactly keeps each of them fighting.

Which brings me to another character who is relatable and instrumental for queer girls in the series, Juri Arisugawa — and not just because she is explicitly queer herself. Juri’s crush on her (ostensibly) straight friend Shiori, and losing Shiori to a boy, has hurt her irreparably, and formed the basis of Juri’s unsentimental, cynical attitude in the series. In her analysis of the character, anime reviewer JesuOtaku writes:

Love is an ugly word for Juri. Her unrequited feelings for a straight woman are a part of herself she can’t change, and isn’t ashamed of, but would be perceived with scorn and condescension from the world around her and worse, the object of her affections. Utena’s childhood dreams of becoming a noble prince who loves and protects the weak are insulting to Juri. That’s not how the world works, [she thinks]. You don’t get to change who you are or how you feel or how the world sees either of those things. Love is a weakness for others to hold against you. Nobility is an illusion for those who’ve never faced hurt and hardship. Hide your weaknesses, bolster your strengths, and earn your right to command the perceptions of those around you. Protection can only be offered in a world where no one knows you’re flawed, weak and hurting.

Obviously, that’s kind of a messed-up way to see the world; Juri’s been forced by trauma (because Shiori didn’t just reject her, but is remarkably good at twisting the knife) to grow up too fast, something a lot of characters do in Utena, in different ways. But the particular way that Juri’s been forced into cynicism by life is one that is particularly relatable to queer people. Every teenager struggling with their sexuality and hormones experiences the fear of rejection, the fear of what would happen if the person you adore not only doesn’t share your feelings, but makes a mockery of them. But the stakes are particularly high for queer people, because we face not only rejection from our love interests but from society at large, and society has particularly cruel ways of twisting that knife by denying us equal rights and continually reminding us that we are the Other and not to be trusted. Even from our individual object of affection, the mockery we’re potentially opening ourselves up to by being honest about our feelings, goes much deeper than simply being about an individual crush. It’s about our sexuality as a whole.

Utena herself, of course, struggles with her feelings for Anthy in her own way, and in a way that shows how much queer girls are dealing with a double-edged sword when it comes to traditional gender roles. She wants to be herself — her more-masculine-than-feminine self — but she also wants to be accepted by her peers. And loving a girl just makes her different in a further way. It was yet another thing I related to with her, as so much of what kept me closeted as a teenager was “I’m already a weirdo in every other way, do I have to be weird in this way as well?” Being into boys — as she clearly is as well — allows her to be normal. But so much of what the boys want out of her is at odds with who she really is and wants to become.

It says so much that I’ve been talking for so long about these themes, and yet only scratched the surface of what there is to discuss here. Revolutionary Girl Utena is one of the best anime for people who love to analyze media, tear it apart and work out its kinks, as all of these ideas are buried under layers and layers of symbolism and allegory. It’s not the show for those who like their media to be clear and explain things to them. It’s also not something I would recommend to those who are triggered by depictions of sexuality involving dubious consent, as there are quite a few examples of this later in the series, including involving incestuous pairings. While the actual sex isn’t shown on-screen (since this is a shoujo series, aimed at teenage girls), and it’s not excused or romanticized, the emotions and reactions of the characters involved are portrayed quite explicitly, and thus those could possibly be (and are likely intended to be) upsetting.

If neither of those keep you away, however, Revolutionary Girl Utena is pretty essential viewing for the feminist, queer media consumer who wants to learn more about the anime genre. It is the sort of show that will keep you thinking about it for days after you finish it, both because it so often defies explanation, and because what you do understand resonates so clearly with the queer girl experience.

How to watch it: If you’re in the U.S., the English dub of Revolutionary Girl Utena was recently uploaded in full to Hulu. However, this is a series that even people who love dubbed anime recommend be watched in Japanese with subtitles. For that, you’ll have to scour some not-so-savory corners of the Internet, or buy the DVDs on Amazon.