Recent EU Court Ruling Might Make Life Less Miserable For LGB Asylum Seekers

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled last week that persecution on the grounds of sexual orientation is considered grounds for asylum to be granted in the European Union (EU). It identifies LGB people as members of a “particular social group” that is deserving of asylum protections should that membership place them at risk of harm in the country of their nationality, as per the language of the United Nations (UN) and EU agreements that guide asylum and refugee legislation in the region.

The term “refugee” shall apply to any person who […] owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.

– Article 1, 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (UNHCR)

The preliminary ruling is expected to set in motion EU-wide changes in legislation pertaining to LGB asylum seekers. Up till now, neither the UN 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor EU Council Directive 2004/83/EC explicitly recognised sexual orientation as grounds for asylum. Individual EU member states, however, may have already recognised LGB/T people as constituting a protected “particular social group.”

The ECJ is a major court in the Court of Justice of the European Union, based in Luxembourg

via Gwenaël Piaser / Flickr

The issue was brought to the attention of the ECJ, the EU’s highest court in the matters of EU law, due to a case in the Netherlands involving three men from Sierra Leone, Uganda and Senegal who are seeking refuge in the country due to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted in their countries of origin by reason of their sexual orientation.” A Dutch court initially rejected the asylum petitions, claiming that the men could “exercise restraint” to avoid persecution. However, the Netherlands Raad van State (Council of State), which is hearing the cases at final instance, consulted the ECJ for a preliminary ruling because asylum is an EU-level issue.

This ruling is what is at the centre of recent media attention. It made three main points:

- First, as mentioned earlier, LGB people constitute a “particular social group” that is protected by both the UN Refugee Convention and the EU Council Directive.

- Second, the existence of laws criminalising homosexuality is insufficient basis for asylum considerations. The risk faced by LGB asylum seekers must be “sufficiently serious” to be considered persecution, i.e. those laws must be actively enforced.

- Third, LGB asylum seekers cannot be expected to conceal or exercise restraint in expressing their sexuality. The ECJ press release states that the court believes “a person’s sexual orientation is a characteristic so fundamental to his identity that he should not be forced to renounce it.”

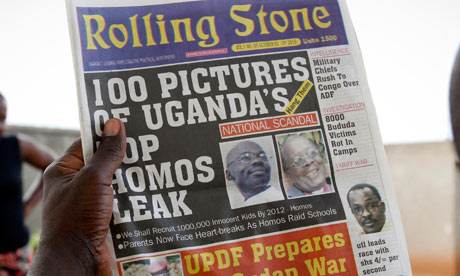

“100 Pictures of Uganda’s Top Homos Leak”

via The Guardian

To better understand the impact this ruling could have across the region, it helps to first consider how much sway the ECJ has over national legislative frameworks as well as the current situation for asylum seekers in the EU.

The EU, which represents 28 countries, is working towards an eventual transition to a “Common European Asylum System” that recognises that asylum is a fundamental right and that granting it is an international obligation. Standardising laws pertaining to asylum seekers across member states ensures that the asylum process doesn’t become a lottery, i.e. asylum seekers should be expected to be treated uniformly and fairly no matter where they end up. Regional legislation is also in place to ensure that asylum seekers do not apply to other countries within the EU if they are rejected by the first country to which they apply.

With regard to the particular case of the three asylum seekers, the ECJ can only clarify the validity or interpretation of EU law and cannot actually settle the dispute. This remains the prerogative of the Dutch courts. Now that the ECJ has clarified its position on the issue, what the Netherlands Raad van State eventually rules on the fate of the three men will then set legal precedent for other courts and tribunals within the country.

National courts always have final say in the application of EU law

via Reformatorisch Dagblad

It is hard to say with any certainty how much regional EU law influences national asylum legislation and processes across the board. On one hand, due to the Schengen Agreement, internal borders among member states of the EU and certain non-EU states (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) are considerably relaxed, e.g. you do not need a passport to travel from France to Spain to Italy. This incentivises a common – or at least similar – policy on asylum seekers; when national borders are no longer as heavily enforced, who one country lets in or keeps out directly impacts your own population.

On the other hand, national sovereignty still reigns supreme. This is perhaps clearest in the UK, one of two EU states (the other being Ireland) that are not part of the Schengen Area: the Borders Act 2007 significantly stepped up restrictions on and monitoring of non-EU migrants, including asylum seekers and refugees. National borders, especially of countries that have more clout in the EU and can expect to face less backlash from other member states, can be temporarily reinstated. After the Arab Spring, France and Germany threatened to reinstate border checks in order to prevent Tunisian and Libyan refugees that Italy had granted temporary residence permits to from entering their countries.

Tunisian refugees disembark at the port of Civitavecchia, near Rome

via The Telegraph

Furthermore, a 2010 report by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) found that rates of success of asylum applications vary wildly from country to country.

According to Eurostat figures, protection rates (refugee status and subsidiary protection) for the same groups of asylum-seekers vary considerably from one Member State to another. For instance, protection rates for Somalis in 2009 ranged from 4% to 93%. Germany and the Netherlands received the largest numbers of Iraqi asylum-seekers in Europe that year; Germany recognized 63% whereas the Netherlands granted protection to 27%. For Afghan asylum-seekers, the two main receiving countries were the UK and Greece: the UK recognized 41%, and Greece 1%.

The report also condemns the widespread detention of asylum seekers in Europe.

In EU Member States, the detention of asylum-seekers is widely practiced and poorly regulated. Seeking protection is a fundamental human right, not a crime. […] In some countries there is a thin line between reception and detention. Euphemisms such as “closed reception centre” or “obligatory presence” may conceal the fact that asylum-seekers are held in confinement or that their freedom of movement is very limited. Airport transit zones are treated as being outside Member State territory, so national legislation regulating detention does not apply for persons stranded there.

Amnesty International estimates that 600,000 people, including children, are detained in Europe every year for “migration control purposes, mostly with no court decision.” UNITED for Intercultural Action, a European network based in the Netherlands, has been monitoring the deaths of those who have tried to enter “Fortress Europe” since 1993. After the Lampedusa tragedy earlier this year, Italy Prime Minister Enrico Letta granted Italian citizenship to the 366 mostly Eritrean, Somali and Ghanaian migrants who died, but those who survived were crammed in severely overcrowded refugee centres and, for the crime of being “clandestine immigrants,” faced fines up to €5,000.

Politicians have raised fears of “asylum shopping,” i.e. the idea that refugees will move from one country to another looking for the best welfare provisions. There is plenty of popular anti-immigrant rhetoric based on fears of drains on overburdened welfare states, national security and clashes between value systems. In a climate of recession and austerity in which a rise in xenophobia and nationalism is expected to impact the upcoming EU elections, asylum seekers and refugees in Europe today face mounting challenges.

Migrants protest attacks on immigrants by ultra nationalist groups and police operations in Greece, 2012

via Louisa Gouliamaki / RT

Even before facing the risk of being told to “go home and be discreet,” as the ECJ just ruled that courts cannot do, LGB asylum seekers are expected to “prove” their sexuality to border agents and judges. This often goes about as well as you’d expect. A 2010 report by the UK Lesbian & Gay Immigration Group found that lesbians and gay men applying for asylum due to persecution because of their sexual orientation faced higher refusal rates (98-99%) than asylum seekers making other claims (73%), while a 2010 report by Stonewall noted that “[UK Border Agency] staff and judges often assume that a person can only be lesbian or gay if they have engaged consistently and exclusively in same-sex sexual activity. Questions focus on sexual activity and asylum-seekers are expected to share explicit sexual experiences.”

The ECJ ruling does not comment on how authorities are to verify asylum seekers’ sexual orientations, though it is clear that being granted refugee status is highly contingent on what authorities make of this. The difficulties of proving one’s sexuality – even before demonstrating the risk or experience of persecution as a result of it – is significantly harder for those who have been married or who have children. This is especially true of women and bisexual people. If “progressive” queer communities still disregard the identities of bisexual people or those who come out later in life, imagine talking to a border agent about it.

via The Guardian

The issue of LGB asylum seekers in the EU is further complicated by the fact that a legacy of European colonialism is inextricably tangled with a lot of anti-LGBT legislation and persecution worldwide, particularly in Commonwealth countries (otherwise known as the former British Empire). The Kaleidoscope Trust, a UK-based charity, just released a report on human rights abuses against LGBTIQ people across the Commonwealth. Navigating the past, present and future of state violence against LGBT people worldwide involves addressing the damage caused by colonialism and the complicity of present-day governments while avoiding the neocolonial rhetoric of “enlightened white people saving the poor brown gays.”

Asylum laws, and in particular, the ways in which the image of the EU is constructed as a safe haven for the world’s persecuted as a result of them, play a big role in this tension. The EU is not necessarily a safe place for LGB asylum seekers and it is not completely divorced from what goes on in these othered, “less tolerant” countries. In the words of feminist writer Flavia Dzodan, who has long been a critic of immigration policies and laws in the EU:

These people, we are told, are escaping conditions outside the realm of our responsibility. The structural poverty, political turmoil, warfare, etc, they face back home has nothing to do with us, or so goes the dominant narrative. In this narrative, the European Union then positions itself as “saving” these migrants by allowing them to stay (as the case might be with some) or alternatively, the European Union is saving us from their scourge by detaining them in inhumane conditions and eventually deporting them (as the case is with the vast majority).

Finally, it’s worth noting that the ECJ ruling does not establish whether people can seek asylum due to persecution on the basis of gender identity. While activists and authorities are often addressing anti-gay laws that specifically criminalise “homosexual acts” or “homosexuality,” it would be amiss to overlook the many ways in which trans* people are also subject to state violence and brutality as a result of the very same laws as well as other discriminatory policies.

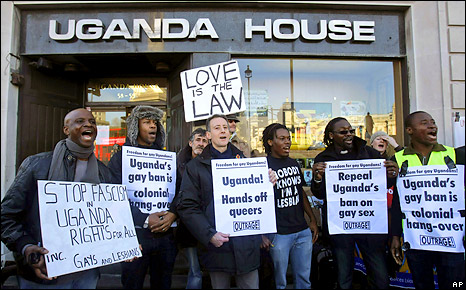

Protest outside Uganda House, London

via BBC

There are reasons to celebrate the ECJ ruling, of course, and in time it might make a real difference to the lives of real people, hopefully starting with the three men seeking asylum in the Netherlands. At the same time, exuberance around this development needs to be tempered with an understanding of the limitations of EU authority as well as serious consideration of the current poor track record on these states’ treatment of asylum seekers and refugees.