Queered Science: Eradicating Misogyny in the Scientific Community

Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer scientists and tell you all about them, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Currently one of the most high-profile queer scientists right now is Dr. Ben Barres, who is a professor of neurobiology, developmental biology, and neurology at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He’s important to us because he’s been vocal in the fight against misogyny in the sciences. He’s also openly transgender, and has extensively discussed his identity and his experiences with the press and the general public.

Dr. Barres was always interested in science since childhood; he remembers playing with chemistry sets, magnifying glasses — all the nerdy things he could get his hands on. He also struggled with gender since he was young: “I was kind of ostracized growing up. I was never in the “in” group. I was always sort of socially rejected. Because I was different. I really was sort of like that boy in a dress, or something.”

He originally went to MIT interested in electrical engineering, but decided to focus on neurology after a particularly inspiring class on the brain in his sophomore year. “I was very intense about my studies. I knew a lot about science, but I didn’t know a lot about other stuff. I was a typical science geek, and I really had no other interests… I was very driven. I worked seven days a week, fifteen-hour days…”

The man himself, in his lab. via ai.eecs.umich.edu

Barres has also described that he felt more comfortable in professional settings than personal ones, because at work he didn’t have to wrestle with the questions of gender identity that haunted him in his personal life. In many ways this echoes what we already know, and what Dr. Erin Cech’s work highlights: that queer students often feel a strong separation between personal and public life, and are constantly juggling a kind of “mental calculus” over where exactly that boundary lies.

“I really felt by that point that life had been so hard on me- I never feel like I really do a good job explaining what it was like, but I didn’t sleep lots of nights, I was suicidal, life was so uncomfortable. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve really enjoyed my life, but somehow it’s like it was split into two parts. The person part, which has been very uncomfortable, and the professional part that’s been a pleasure, and I’ve really enjoyed. But the personal part was just so uncomfortable that sometimes you think, ‘I’ve had enough.’ It’s that distressing.”

At 40, already well established in the science community as a woman, Barres decided to transition. “I did not understand why I was different and I was too ashamed to ever once discuss my feelings with anyone. At the age of 40 years old, I learned about transsexualism, and decided to change my sex. Even though I worried that it would seriously harm my scientific career, I found that the opportunity to become a man was irresistible.”

He says he was in denial about the presence of gender discrimination in the sciences until his transition, at which point he saw first-hand the differences in how people treated him. He tells a now-famous anecdote: after giving a talk shortly after his transition to living as a man, he overheard a colleague say, “Ben Barres gave a great seminar today, but his work is much better than his sister’s work.” This inferior “sister” was none other than Barres pre-transition, and the work being presented was the exact same work. This was an inarguable example of gendered stereotypes of scientific competency at work.

Since then, he has dedicated a significant portion of his work to eradicating misogyny in the sciences. “As is true for many successful scientists, I had never thought much about gender discrimination. It did not occur to me that it was a serious problem. After all if I could attain tenure and full professorship as a woman, why couldn’t every other woman? It didn’t occur to me to think that I just might have been lucky or that I might have been successful by being several times more productive than comparable men in my career cohort.”

Summers left Harvard amidst controversy in 2006.

via wonkette.com

In 2005, the president of Harvard, Larry Summers, gave a talk at Harvard in which he suggested that women are innately worse at science than men. Summers based much of his argument on The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature by Steven Pinker, in which Pinker states, among other things, that men are inherently “risk-taking achievers who can willingly endure discomfort in pursuit of success” and that “women are more likely to choose administrative support jobs that offer low pay in air-conditioned offices.”

Steven Pinker

via telegraph.co.uk

The puzzling non sequitur of air-conditioned offices aside, (what does that have to do with anything?), obviously we disagree, and so did Dr. Barres. He wrote a pointed counterargument called “Does Gender Matter?” published in 2006 in Nature. And just like that, Barres was famous. “This is a street fight,” he says. He pointed out that much of Pinker’s work (and many similar theories as well) is based on evolutionary psychology, a field that has for the most part been strongly trounced. Barres argues that there is no evidence, only speculations on top of speculations, that women are innately bad at science thinking. However, there is strong evidence that prejudice, latent or obvious, against minority groups significantly decreases their success.

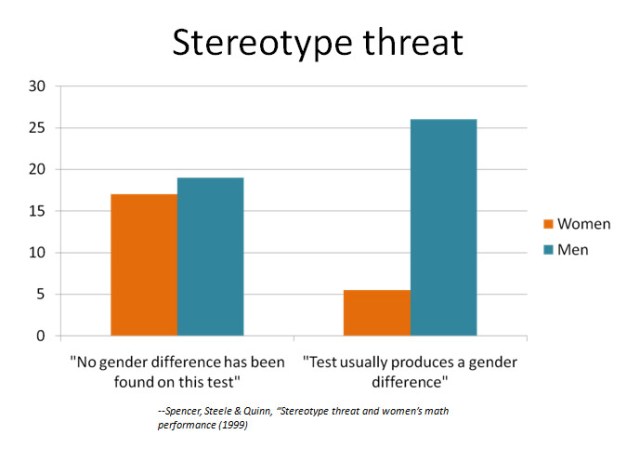

Just as Dr. Erin Cech mentioned last time, stereotype threat plays a huge part in minorities’ success: Barres defines stereotype threat as “the fear that one’s behavior will confirm an existing stereotype of a group with which one identifies… This fear causes an impairment of performance.” So, in practical terms, it’s been proven that women perform far worse on a science test if they are reminded beforehand that women are bad at science.

What’s more, the scientific community should have a huge incentive to minimize exclusion of minorities in the sciences, for its own good; white men account for eight percent of the population, but constitute far higher percentages in the sciences. And the probability of getting the best and brightest minds from that eight percent is incredibly low. The longer we go with such a limited slice of our population, the longer we are only shooting ourselves in the collective foot.

After his commentary was published in Nature, other colleagues at Harvard used slurs about his transgender status to denigrate his work. Barres reports that Harry Mansfield called him a “political fruitcake,” and Steven Pinker said that Barres had “reduced science to Oprah.” Both of these men are also professors at Harvard. Regardless of the fact that these insults are glaringly unprofessional and inappropriate to any work setting, their spluttering inability to come up with coherent objections to his work shows that they have no real support for what they’re saying. Keep in mind that Mansfield, a philosophy professor, has also stated in the past (in his 2006 book Manliness): “Is it possible to teach a women manliness and thus to become more assertive? Or is that like teaching a cat to bark?”

Obviously these guys need to revise their gender beliefs a little, and it’s disturbing that they are professors of psychology and philosophy at Harvard. They occupy positions of moral and intellectual authority, and it seems frankly irresponsible that the leaders of schools like Harvard continue to allow this kind of ignorant rhetoric from teachers and mentors. Oh, but I forgot – the president of Harvard is the one whose sexist comments started this controversy in the first place. That was dumb – but I am a woman, after all.

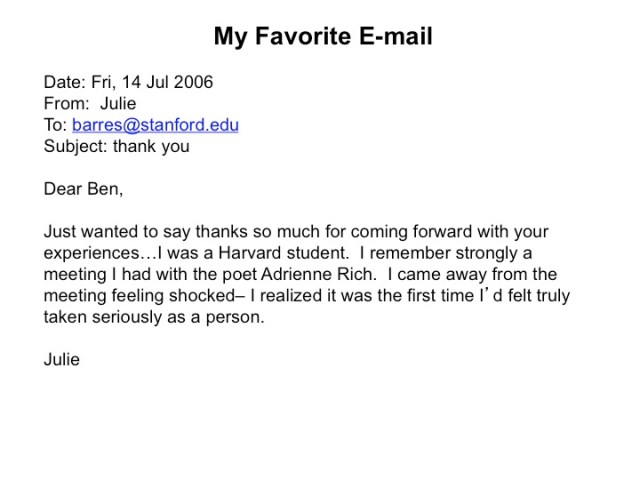

In general, their way of thinking is on the way out – thankfully. The vast majority of emails that Barres receives on this topic are overwhelmingly positive. Look at this one, for instance:

via Ben Barres

Things like stereotype threat and internalized prejudice don’t just apply to women, they also apply to any other minority status – like queer or trans* identities.

Barres spends a lot of time speaking openly and publicly about his transgender identity, in the hopes of supporting other LGBTQ scientists.

“I have become aware that there are many students and academics who are gay who are still closeted, even in the Bay Area, for fear of harmful repercussions to their lives and careers. I always advise them to be open about who they are, including on job interviews, and I have yet to see one not get their first choice job. Your difference is your greatest advantage. Don’t let others take your happiness away.”

He is an inspiring example of using positions of power to effect social change. While he says his colleagues at Stanford (in an open-minded and liberal part of the world, it should be noted) have been overwhelmingly supportive — not everyone is. “I am tired of powerful people using their position to demean me just because I am different from them…I will certainly not sit around silently and endure them.”

Download slides from his basic talk.