Queer Harlem: From LGBT Icons of the Harlem Renaissance to Invisible Me

I entered college with three things: a love of poetry, a strong sense of Black Pride and a boyfriend. I left college with a BA in Writing and ethnic studies, and—perhaps in the typical Sarah Lawrence fashion—a girlfriend. During those four years I went on some sort of journey, the catalyst being a sudden dive into a group of academic, queer, and Black men and women. It’s a journey I am still on, and can’t exactly put into words. I was openly queer in high school, to anyone who would listen, as my grandfather (a Korean war vet who had raised me as a single father) had gone selectively deaf when I came out to him as bisexual. When I left college, I found myself with a better-informed sense of militancy and much more comfortable with the thing that had been haunting me for years: I am a lesbian.

There were obvious reasons I’d been worried all my life about ever calling myself the “L” word: religious family members or misguided classmates, and the understandable desire of every human being to fit in with the majority. But my habit of toting around boyfriends by day but spending nights between women’s legs pointed to something bigger, something deeper. It wasn’t until my senior year of college, when I found myself wanting to write about a jazz singer during the Harlem Renaissance, that I discovered Gladys Bentley, a woman blues singer who frequented Harlem speakeasies, romancing ladies with her alto voice, and modified lyrics to popular songs—all while wearing a tuxedo.

I’m sorry, what?

I remember staring at my computer screen, thinking about Baldwin and Langston Hughes—the only two Harlem Renaissance artists I could name who I knew were queer or at least comfortably rumored to be so. This led me to Countee Cullen, whose poems had sat on my bookshelf when I was a child. They were bought for me by my grandfather who must not have known the truth, or I could guarantee I would never have even set eyes upon the covers. They were all men. But here was Gladys, with her top hat and her Drag Queen back-up singers. And here I was, having never heard of her before this moment — not to mention having never known that Josephine Baker had dated Frieda Kahlo. Why was that?

It didn’t dawn on me until I came out to my family, and the resulting events introduced me to a lesbian cousin I never would’ve known I had. She was never spoken about, just as no one had mentioned that Langston Hughes was gay when we read his poems in elementary school. I was noticing a pattern.

If Queer people were invisible, Black Queer people were even more so.

This made it even harder to discuss. I grew up in the south Bronx, where the only people I knew to be gay were Latino/a. Specifically, there was one man who would smoke his cigarettes in the morning, standing in the doorway of the building across the street, draped in a pink bathrobe with his short, graying black hair slicked to shine; and two Puerto Rican girls who were my image of ‘butch’ for most of my life, with their boys’ cargo shorts, piercings and ponytails. I didn’t see — or perhaps I was guilty of perpetuating invisibility myself — any black lesbians until I was older, in Harlem. I saw my first studs and AGs, and I understood there was room for me, the Black girl who wasn’t straight.

I spent a lot of time in Harlem. I shopped on 125th street, ate at Amy Ruth’s, bought hoop earrings in Little Senegal and whenever possible, I’d see all the movies I could at Magic Johnson’s Theater. As a young spoken word poet, I dreamed of moving to Chicago, just to be around the space where the other half of the Harlem Renaissance took place. Even when someone doesn’t know the range of the artistic revolution that was the Harlem Renaissance, they know the name. They know writers like Claude Mckay or singers like Ethel Waters but they may not know them as Queer Black Americans. Why is this?

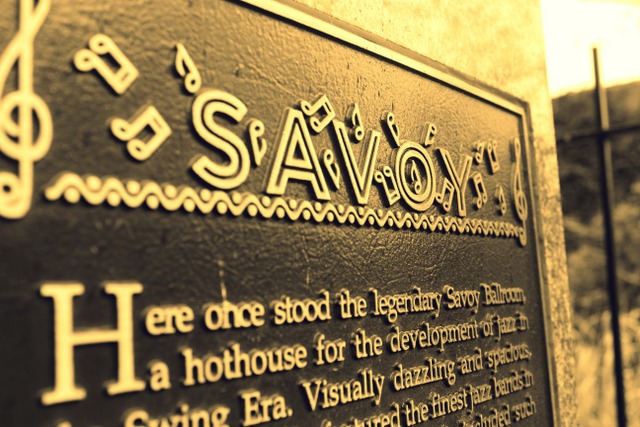

Harlem during the 20’s and 30’s wasn’t about “coming out”, and relationships were relatively open. Gay culture wasn’t segregated the way it is today — no “gay clubs” were needed. Homosexual and heterosexual people alike partied in the same venues; The Cotton Club, the Savoy and Rockland Palace all held Drag Balls as well as hosted many straight performances.

At times it seems like past-Queer Harlem had a better view of what queerness meant than we do today. Back then, if a woman slept with a woman, it didn’t necessarily make her a lesbian. In Josephine: A Hungry Heart, Jean Claude Baker speaks about how women performers often shared hotel rooms and had affairs. However, he does go on to say that if a woman flat-out refused a man she was derisively labeled a “bull dyke.” There is always a point where discrimination rears its ugly head. While there was visibility in Queer Harlem then, it’s now cloaked in invisibility. It took me so long to discover queerness in that time period that I had to teach myself about it.

These renaissance men and women were the heroes of people like my grandfather, people who might have completely written off their accomplishments had they known about their personal affairs. I wonder if the invisibility began there, as a ‘look the other way’ attitude. And did our Black heterosexual ancestors pass this on to us? Is this why Queen Latifah’s relationship with her personal trainer has gone so unnoticed by the general population? Is this why no one knew about Robyn, Whitney Houston’s rumored lesbian lover? Are we so willing to look stupid, as stupid as the onlookers in the juke joint as Shug Avery sings a love song to Celie? If we continue this, there will be no hope for a positive public image of a Queer Black person and we’ll be forced to swallow sad, offensive excuses for non-hetoronormativity, a la Nicki Minaj.

When Pariah came out, I was as happy as a couple spending their wedding night in a five-star hotel. I risked missing it just to wait until it was showing in Harlem, not even sure whether it would. If I was going to see the film (which I thought was lovely), I was going to see it in my ideal environment, surrounded by queer people of color. My love for Harlem as a community runs so deep that I cried when they built the first Starbucks — gentrification makes its huge mark. As being gay in America is primarily a “white thing” — the sort of flamboyant men you see in Bird Cage and the sort of butch women you see in Monster — I’m sure the gentrification will bring more queerness in the community. But once again, Black Queerness is moved to the side, out of sight and out of mind.

I have rather large dreams for myself: to become a well-known (okay, famous) Black, lesbian fantasy writer. I want to bring queer characters to the forefront, with stories that aren’t just centered on their sexuality. But it dawned on me when I spoke to my newly discovered gay cousin that one day I might be the one who isn’t spoken about, the leper of the family. “The one who ran off to Brooklyn with her girlfriend, who writes those books we don’t let our children read.” I’ve found a thriving Black Queer culture in Brooklyn, and on restless nights I tell myself we didn’t get wiped out of Harlem, we just moved, we migrated. We’re here, we’re queer, we’re not actually invisible.

It’s very hard to believe myself.

All images are courtesy of Siliah J “Sil” Nelson of F3ARL3SS PHOTOGRA4HY. siliahj [at] gmail [dot] com.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.