Queer Crip Love Fest: Talking with Queer Disabled Latinx Activist Annie Segarra about Family and Connection

My girlfriend told me she loved me on election night. The rest of that evening is either blurry or so sharply detailed that it actually hurts to recall. But I think back to the moment she said it happily and often. I remember thinking “no matter what else happens, the person I love loves me. I’m not alone in any of this. So now I have to do better.” Since then, I’ve gotten braver: talked back more and shut up less, trumpeted my worth and my friends’ achievements, given my intelligence some teeth. It would have happened anyway, but knowing I have someone to stand next to upped my game a whole lot faster. If I don’t fight my best fight, I’m not just letting myself down — I’m part of a team that will hold me accountable. And that realization got me thinking about what love looks and feels like for disabled folks in particular.

Know what you get when you Google “disability and love”? Page after page of articles on the “damaging myths” that plague our dating lives; reminders that yes, of course we can have sex; and, best of all, praise for “overcoming stereotypes” by managing to score able-bodied partners. Message received, internet: romantic love (particularly from an able person) is the only kind that counts. It’s our punch card into the “real world,” the validation we need to become worthy of opportunity, the end goal when we see ourselves in movies and TV every last one of those search results. It’s how we’re supposed to secure equal footing with “normal” people. If one of them wants us, we must not be too scary or too much. We must be Good Disabled — the ultimate endorsement.

But what about everything and everyone else we love? It’s not like I languished in woe and despair until my able-bodied girlfriend showed up. Disabled people’s lives are bursting with affirmation, affection, and meaning well beyond the half-baked romance narratives we get stuck with. So say hello to Queer Crip Love Fest, a new series where I talk to disabled queer folks about the love all around them — for partners, family, friends, pets, fictional characters, whatever — and share it with you right here on Autostraddle.

To start, I caught up with Annie Segarra, a queer disabled Latinx activist and YouTuber from Miami who advocates for diverse media representation, accessibility, and “uplifting intersectional and marginalized narratives.” We talked disability in social justice communities, her relationship with her sister, and what would have happened if Frida Kahlo had the internet.

Let’s get right to the big stuff. One reason I started Queer Crip Love Fest was to question this assumption that disabled folks aspire to love but never actually experience it, and that “love” always means romance and sex. What are your thoughts on that?

It’s such an exhausting topic, and I haven’t even begun to get into it, really. I feel a little inexperienced with it and I feel inexperienced in general, because I still feel so new, and I feel like there’s a lot socially that I may not understand. There’s a lot that I do understand, but there’s a lot that I don’t, because I’m a disabled baby — like a gayby. I’ve only been out as disabled for about three years.

I didn’t realize that!

I started losing physical ability in mid-2014, almost three years ago. So whenever someone asks me what dating is like as a disabled person, I’m like, “I just became one.” I haven’t had any of that experience yet. I’m sure there are other disabled people who have had disabilities their whole life and have never dated either, but that’s kind of how that question makes me feel. I’m still too young in the disability world to have any feedback on that.

Absolutely, and that’s a great parallel with queer experience.

The spectrum of what’s possible, the spectrum of what queer sex is gonna be like for me, I feel like there’s gotta be ways. I have trouble currently seeing how physical disability will be an obstacle there. But topics like that, dating and disability, I still don’t know yet and so I’m still pretty nervous about it.

I’ve had sex a few times in the past three years, but there wasn’t really a difference because I hadn’t lost as much ability then. So with my ability being what it is at this moment, I don’t know how that works, and I don’t know how queer sex is gonna work. So that’s where I am now — with the whole road ahead of me. I used to be a top, and now I’m like “can my wrists handle it? I don’t know!” We’re gonna find out, I guess.

“Whenever someone asks me what dating is like as a disabled person, I’m like, I just became one.”

Right! And that’s kind of why I wanted to get away from exclusively talking about romantic relationships, and exalting them as the only way to express love. Also, there’s this morbid fascination around disabled people’s sex lives.

That fetishization is triggering as fuck, and I hate it. That was a whole new thing to deal with in becoming disabled. I’m a rape survivor, and a big part of that was that I felt objectified and fetishized for being Latina and indigenous-appearing, and ambiguous. So I already felt fetishized as a woman of color, and for my body shape and size. I hated when people made comments about me having a big bottom and stuff, because it feels bad. And then to add the fetishization of being a wheelchair user on top of that, I was like “fuck, why? Why is the world like this? Holy shit. I can’t catch a break, man.” It just sucks that people are so obsessed with sexuality and disability. And I think it’s because it’s seen as a fetish, and not normalized like able-bodied sexuality is.

So in terms of other kinds of love, the person I really want to talk about is my sister Emily. She’s one year younger than me, she’s my best friend, she’s autistic, and we take care of each other. I just love her energy and being in her presence.

Have you had any of these conversations around queerness with her?

No. My sister is generally not very verbal, so language is not necessarily the way that we communicate, which is a really cool part of our relationship. We have to find other ways. So now it’s really interesting — we swap help with one another. For the majority of my life, I’ve been helping to care for her and have her back on a multitude of things. When we go out together, she wants to be independent, but she has to learn the language to communicate with people. So either she will gesture to me or hand me something that she wants to buy and I’ll do the talking with the cashier, or sometimes she wants to do it herself and I’ll give her the language. Kind of like an interpreter. I’ll give her the words that she needs to communicate with that person.

“Language is not necessarily the way that we communicate, which is a really cool part of our relationship. We have to find other ways. We swap help with one another.”

I’ve never heard that interpreter analogy before, I like it.

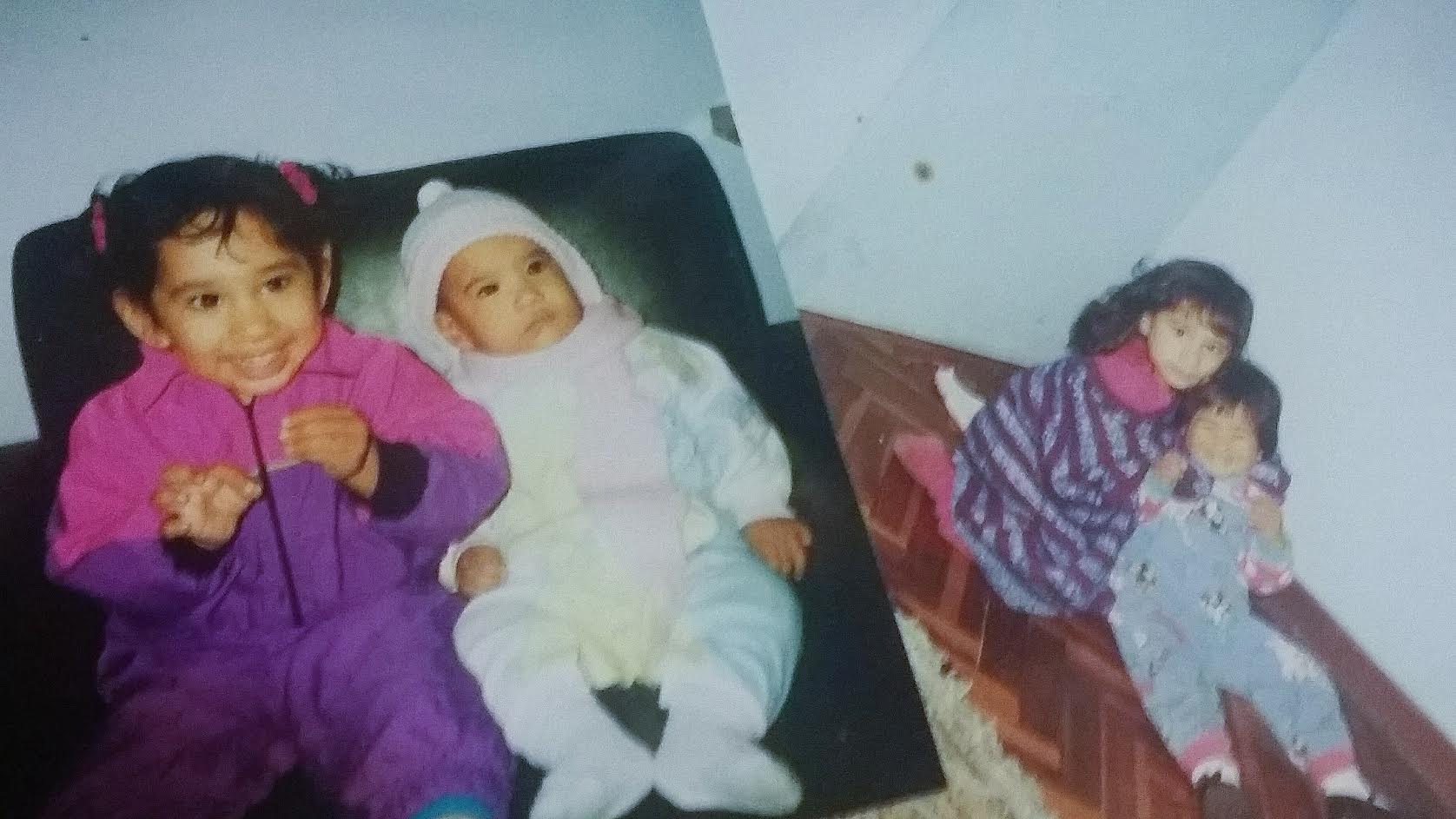

I feel like that intensifies our relationship too, that a lot of it is nonverbal communication. ‘Cause that’s very different than how I communicate with anyone else that I know. And we’ve been communicating that way so intimately for our entire lives. She was diagnosed as autistic when she was two and I was three. From that moment, I felt compelled to be like “my sister’s gonna be fine, I have her back. I’m gonna help her and she’s gonna stick by my side no matter what. We’re gonna go to college together, we’re gonna live together, we’re gonna be moms together, we’re gonna do everything together.”

“Nobody’s exempt from ableism — including disabled people. Ableism is in all of us because of the systems that we’re living in. I loved my sister and therefore I understood that she deserved justice and she deserved respect and she deserved the best. But there are times that I probably babied her and she didn’t want to be babied.”

Why do you think you saw it that way?

Because it was already love at first sight. I already loved her, at that age. I’m the oldest, and so I had her to myself for a few years. And the moment I first saw her — there are videos of this — I was like “this is my best friend.” I just instantly felt very connected to her and didn’t want to let her go. So when I found out she was autistic and needed some extra help, then I immediately thought “well yeah, I’m gonna help her.” It made a little advocate out of me.

Has becoming disabled — and an advocate in the community who’s very visible online — changed your relationship with her?

Someone recently asked me if having an autistic sister absolved me of ableism, or if I got into disability politics because of her. And I had to say no, nobody’s exempt from ableism — including disabled people. Ableism is in all of us because of the systems that we’re living in. I loved my sister and therefore I understood that she deserved justice and she deserved respect and she deserved the best. But today I catch myself, because of her oral ability being what it is, there are times that I probably babied her and she didn’t want to be babied. There’s still that weird line of “is it ableism or is it because I love her like my child?” Because a parent of a nondisabled child will still pinch their cheeks when they’re 30 and be like “my baby!” That’s kind of my relationship to my sister, and I’m like “is that ableism or is that ’cause I love her like my own kid?” So I definitely still question myself on that.

Have you reached any resolution, or is it kind of an ongoing conversation?

I try and read her better — watch for her cues a bit more. Because I realized I wasn’t watching that. I feel like I was just treating her like a teddy bear or something, and I understood more that I was maybe thinking more about myself and how I wanted to communicate love, and not necessarily what she wanted to receive.

Sometimes we need to adapt to what other people’s needs are instead of focusing on our own instincts. Like “is this the appropriate time to say the thing that I want to say? Probably not.” Read what that person needs rather than what we feel in that moment. Because honestly, that kind of instinct is more about anxiety. It’s about relieving anxiety from ourselves, but not necessarily giving someone else the space or resources they need to go through whatever they’re going through.

“The way I receive love has changed. That being said, it hasn’t meant me living without love at all. It’s been just transitioning from one way of life to another.”

I think that’s crucial for anyone, especially if you’ve got a disabled person you love in your life or are interacting with us out in the world. Because it hits on lots of sensitive areas: self-determination, independence, being believed when we assert what we want, or even just wanting something, period. Does any of that weigh on you?

I feel like a big part of my experience of transitioning into disability has been isolation. If anything, my isolation has kind of made who I am a little more needy, because I’m already kind of needy in social interactions. That’s how I need to receive affection: physically, hugs and stuff. That is how people would communicate love to me. Usually, I feel like I have to be reaching out. So if someone else is doing it, it feels a whole lot better than me making myself vulnerable all the time.

Isolation and bed rest are lonely and depressing. I kind of felt like I disappeared. Because when you get sick, and you’re stuck in your room and in bed, everybody else’s life just keeps moving forward and you are at a standstill. I don’t want to put disability in a bad light, because so many people are advocating for how disability is no different than any other identity — but then again, I want to differentiate illness and disability that is not illness. Illness and chronic pain is something that I can’t really accept as part of my identity as much as it is something that I have to fight all the time — in comparison, at least, to other disabilities that may not cause pain. There’s language I still need for that and I’m working on it. I don’t know if the day will come or if I’m supposed to, as a disability activist, love my disability. Because I’m like “my disability is my pain.” And I don’t know that I could ever truly say I love my pain.

The pain is exhausting! It does take a lot out of you.

So the way that I express myself in love is the same as before — maybe just heightened, even. But the way I receive love has changed, because I’m usually here in my room. So it’s more expressed to me in a verbal or written way, not necessarily from physical interactions. That being said, it hasn’t meant me living without love at all. It’s a change and it’s an adjustment — just like losing abilities has been an adjustment — which can be tearful and sad because you’re grieving over the change. So while I used to be able to go out and be in the city and be that able-bodied girl, now, no. But the love that I’ve received through people like my sister, who’s one room away, or through the internet and the disability community has been just transitioning from one way of life to another. The internet is amazing.

“A lot of disabled people are very aware of [identity] intersections themselves. Many other activists are not, because most don’t give a shit about disability rights if they’re not disabled. How do we fix that? How do we get other activist communities to include disability rights in their missions?”

The internet’s given the disability community a huge boost.

I mean, we’re very lucky. I think about Frida Kahlo all the time, because she’s like, the intersectional representation of my life: a queer, disabled, feminist Latinx with chronic pain who lived most of her life on bed rest, too. Her disability rights beliefs are questionable, but this was also the ’50s, so I don’t really blame her. She was very progressive for her time. When I see someone like her, specifically, it gives me representation of disability that’s totally doable. She totally did it. She was a queer, brown artist and feminist with chronic pain that kept her in bed and isolated all the time. I’m like, “damn, I struggle with all these same things and I have the internet.” In that time? Oh my god! That’s why she never connected with the disability community, in my opinion, because she was isolated. All she had was herself and the able-bodied people that surrounded her. What magic could have fucking happened if homegirl had the internet?

So we’re all very lucky to be able to connect with one another, make these connections really fast through the content we’re creating, and push our visibility into the mainstream.

Have you found that to be the case with other communities online?

As disabled activists, our work tends to be incredibly intersectional for several reasons. For one, I think our activism tends to be at the bottom of the list for everybody else. And if we are intersectional people, like being women or nonbinary or queer romantically and sexually, or people of color, a lot of disabled people are very aware of the intersections themselves. Many other activists are not, because most don’t give a shit about disability rights if they’re not disabled. How do we fix that? How do we get other activist communities to include disability rights in their missions? The only solution I can come up with right now is that we have to be the ones reaching out, because they aren’t necessarily going to.

Other activist communities are very aware of one another. Trans rights, gay rights, racial issues and people of color — they’re aware of one another. But all of them lack an awareness of disability rights issues. The question is, is it because they don’t care? is it because we’re not visible enough? Why do we know about their issues but they don’t know about ours? Is that their visibility, or is it that we’re invested in learning? So if we can find that answer, maybe that’s also the answer for them.

Check back for the next installment of Queer Crip Love Fest, which will be running biweekly beginning in January!