Pure Poetry Week(s):

#1 – 2/23/2011 – Intro & Def Poetry Jam, by Riese

#2 – 2/23/2011 – Eileen Myles, by Carmen

#3 – 2/23/2011 – Anis Mojgani, by Crystal

#4 – 2/24/2011 – Andrea Gibson, by Carmen & Katrina/KC Danger

#5 – 2/25/2011 – Leonard Cohen, by Crystal

#6 – 2/25/2011 – Staceyann Chin, by Carmen

#7 – 2/25/2011 – e.e. cummings, by Intern Emily

#8 – 2/27/2011 – Louise Glück, by Lindsay

#9 – 2/28/2011 – Shel Silverstein, by Intern Lily & Guest

#10 – 2/28/2011 – Michelle Tea, by Laneia

#11 – 2/28/2011 – Saul Williams, by Katrina Chicklett Danger

#12 – 3/2/2011 – Maya Angelou, by Laneia

#13 – 3/4/2011 – Jack Spicer, by Riese

#14 – 3/5/2011 – Diane DiPrima, by Sady Doyle

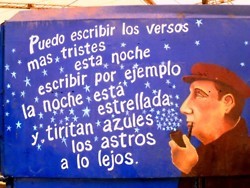

#15 – 3/6/2011 – Pablo Neruda, by Intern Laura

![]()

I liked Pablo Neruda from the moment I heard that he wrote a book called “20 Love Poems and a Desperate Song.” It was a while before I actually read any of his poems, but he was worth the wait.

| Tus Pies

Cuando no puedo mirar tu cara Tus pies de hueso arqueado, Yo sé que te sostienen, Tu cintura y tus pechos, Pero no amo tus pies |

Your Feet

When I can not look at your face Your feet of arched bone, I know that they support you, Your waist and your breasts, But I love your feet |

Because the thing is, not all the good poetry is in English. People have said all kinds of beautiful things in thousands of languages. The good news is that we have translations. The bad news is that there are some things that don’t travel well from one language to another. For me, that means learning other languages, even if it’s just a little bit. Por ejemplo:

Libro de las Preguntas

LXVI.

| Echan humo, fuego y vapor Las o de las locomotoras? En qué idioma cae la lluvia Qué suaves sílabas repite Hay una estrella más abierta Hay dos colmillos más agudos |

Do the o’s of the locomotive cast smoke, fire and steam? In which language does rain fall At dawn, which smooth syllables Is there a star more wide open Are there two fangs sharper |

I know what poppies and jackals are, but I wouldn’t have any idea what he was doing with the words if I didn’t look at them in Spanish. Just because I like this poem, let’s look at my favorite section.

XV.

| Pero es verdad que se prepara La insurrección de los chalecos?Por qué otra vez la primavera Ofrece sus vestidos verdes? Por qué ríe la agricultura Cómo logró su libertad |

But is it true that the vests are preparing to revolt?why does spring once again offer its green clothes? Why does agriculture laugh How did the abandoned bicycle |

Can’t you just see the bicycle flying down the road? Other things you might want to know about Pablo Neruda are that he named himself that, he only wrote in green ink, he wrote odes to lots of things (his socks, the artichoke, big tunas), and he supported the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. Spanish Republicans are not like American Republicans, they were the ones against Franco, who was about as oppressively right-oriented as you can get.

If you like what you see, don’t stop with Mr. Neruda. I would recommend Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer and Wislawa Szymborska. The limits of your language don’t have to mean the limits of your world.