Prop 8 Gay Marriage Trial Explained Part 3: How Do We Win This Thing?

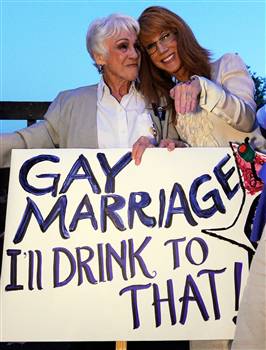

![]() Another week of the Proposition 8 gay marriage trial is over, and you know what that means! Yes, that you got four more glorious recaps of the action. BUT ALSO Jessica, your favorite lawyer ever, is back to explain everything to us laypeople!

Another week of the Proposition 8 gay marriage trial is over, and you know what that means! Yes, that you got four more glorious recaps of the action. BUT ALSO Jessica, your favorite lawyer ever, is back to explain everything to us laypeople!

Last time, Jessica told us about the equal protection clause. Specifically, she explained how our side is trying to prove that Prop 8 violates that clause because it discriminates based on sexual orientation.

This time around, she’ll explore Team Totally Right’s other arguments — there are several! So here we go, these are all the possible ways we could win this thing, it’s like a choose your own adventure book but a judge gets to do the choosing:

If you support marriage equality, it’s obvious to you that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation violates the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution. And even if you don’t understand the legal rationale, that discrimination seems inherently wrong.

Conveniently, there’s a good argument from a legal standpoint, too. So with a strong legal argument and a convincing message, can’t we just focus all of our attention on equal protection?

No.

I. We Got 99 Reasons but They Just Need One

Effective advocacy can’t stop with one convincing argument. Our side wants to ensure they’re providing the judge with multiple paths to rule in our favor.

For example, take the arguments regarding discrimination based on sexual orientation. Obviously, our attorneys argue, discrimination based on sexual orientation warrants some form of heightened scrutiny — either intermediate or strict. Proposition 8 is neither “narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest” nor “substantially related to an important governmental interest,” which means that regardless of which level of review the court selects, we win! But, if through incomprehensible twists and turns of logic the court doesn’t decide that classification based on sexual orientation warrants heightened scrutiny — well, we still win. The government has no legitimate reason for denying marriage equality. So using the rational basis test, Proposition 8 must be overturned.

But what if the court doesn’t agree with us there, either? Then we need alternative arguments. So, in addition to arguing that Proposition 8 violates the Equal Protection Clause because it discriminates based on sexual orientation, we’re also arguing that this is blatant gender discrimination in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. And in case that’s insufficient to persuade the court to strike down this ridiculous law, Proposition 8 is also unconstitutional because it violates the fundamental right to marry as established by the Due Process Clause.

For Proposition 8 to be declared unconstitutional, we only need the court to agree with us on one of these points. The rationale matters because it will help to define how much this affects future issues pertaining to marriage equality. But for this case, any will suffice. Unconstitutional is unconstitutional; you don’t get extra bonus points because the law violates the Constitution in multiple ways.

II. Gender and the Equal Protection Clause

With that in mind, let’s begin with gender discrimination. Fortunately, the law here is well-established, and therefore much easier to follow. We don’t need to evaluate the four factors to determine whether gender is a suspect class. Since Craig v. Boren in 1976, a law that discriminates on the basis of gender has been subject to intermediate scrutiny. Classifications based on gender are unconstitutional unless the government can demonstrate that the classification is substantially related to an important governmental interest.

We can’t simply jump into talking about what intermediate scrutiny would mean for us, though. We first have to establish that the law classifies people based on gender. This may seem obvious. I mean, I cannot marry my girlfriend in California. If either of us were male, we could marry in California. Seems like a pretty clear classification based on gender, no? But it’s not quite that simple, because it depends on how you frame the issue. As H8ers (and Mark Harris from the Log Cabin Republicans documentary) are happy to remind us, even with Prop 8, anyone is allowed to marry someone of the opposite gender. Based on that logic, there is no classification; everyone is treated the same. So which interpretation is correct?

Conveniently, this issue runs parallel to a case the Supreme Court has already considered. Virginia maintained laws making interracial marriage illegal up until 1967. At the time, those supporting the law argued that it was perfectly constitutional because it treated everyone the same. When declaring the law unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court noted that the mere “fact of application [to both the white and African-American members of the couple did] not immunize the statute from the very heavy burden which the Fourteenth Amendment has traditionally required of state statutes drawn according to race.”

By extension, our attorneys argue in their trial memorandum, the fact “that both sexes — gays and lesbians — suffer from Prop. 8’s discriminatory classification does not render it constitutional.” To uphold the law, the government must meet the heavy burden reserved for these types of discriminatory classifications: intermediate scrutiny. This doesn’t mean we win, it just means that the court must examine the law and its purposes more carefully.

III. Due Process & Fundamental Rights

And if none of these equal protection arguments persuade the court? We turn to the Due Process Clause. In addition to offering one more reason for the court to invalidate Prop 8, this clause offers one more opportunity for mental gymnastics (just in case the gender discrimination arguments were too straightforward).

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment asserts that the government shall not deprive any person of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean that there are certain individual liberties and freedoms that inherently restrict government power. For example, in Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court held that intimate, consensual sexual conduct is part of the liberty protected by substantive due process, thereby invalidating sodomy laws across the country.

In some cases, these liberties are so important as to be deemed “fundamental rights.” When the government interferes with these fundamental rights, the action is subject to strict scrutiny review; to withstand a constitutional challenge, the government must demonstrate that this interference is necessary to achieve a compelling governmental purpose.

But what is a fundamental right? Some things are clearly established as enumerated fundamental rights — the First Amendment guarantees free speech and religious freedom, and these rights are widely recognized as fundamental.

But the Court has also found several fundamental rights outside of the text of the Constitution. For example, Loving v. Virginia provides that there is a fundamental right to marry a person of any race:

“Marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival…. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law.”

When the fundamental rights are found outside of the text of the Constitution, though, legal scholars and Supreme Court Justices debate the nature and scope of these rights. Some believe strongly in the existence of non-enumerated fundamental rights, while others allege that the court is usurping the political process by protecting these rights.

So how do our attorneys persuade the court that Proposition 8 interferes with a fundamental right? They begin with the words of the Supreme Court. Without necessarily recognizing the long-term implications of their assertions, the Court has provided strong guidance. According to Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur, the Court held that “freedom of choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause.” In other cases, the Court has noted that “marriage is the most important relationship in life” and that “choices about marriage” are “sheltered by the Fourteenth Amendment against the State’s unwarranted usurpation, disregard, or disrespect.” This sounds like the language of fundamental rights to me.

But again, this is just one step in the process. Establishing the violation of a fundamental right does not inherently mean we win — it just establishes the appropriate standard of review (strict scrutiny), and the court will determine whether the infringing action is permissible.

So How Do We Win?

Clearly, this is the question everyone cares about. As much fun as tracing the legal analysis may be, the part that matters to everyone on both sides is how it’s going to end. So how does this end?

It depends.