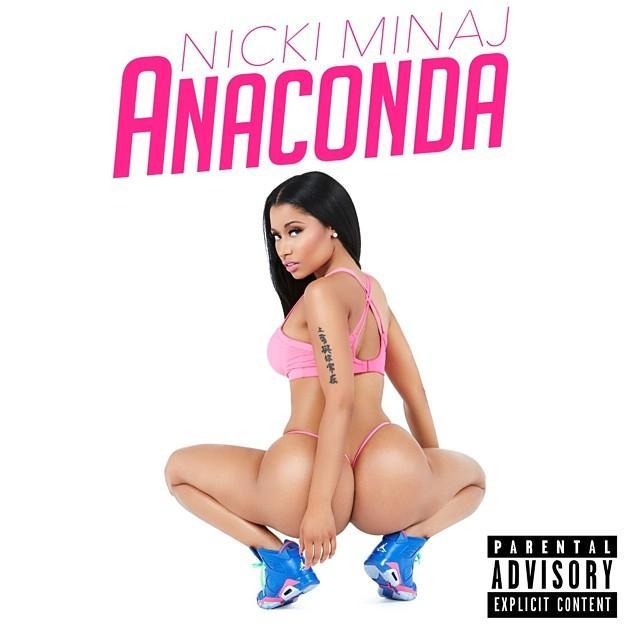

The hype over Nicki Minaj‘s “Anaconda” has been a long process. It started when the cover, which featured a controversial image of Minaj’s behind, leaked on the Internet to much dismay; it continued to play out after the track’s audio release as the lyrics were heralded as feminist gold, and it all came to a much-needed climax in the form of the music video featuring Minaj, some backup dancers, and Minaj’s ass. Oh, and Drake was there.

Folks are now, as usual, scrambling to decide: empowering, or not empowering? If anyone had actually been paying attention to Nicki all these years, they’d already know the answer.

When Beyoncé‘s feminist credentials came under fire by feminists in the past year, there was hell to pay. It was fire-and-brimstone kinds of hell, too. People who expressed distaste for the “Mrs. Carter” tour title or Beyoncé’s subtle sexuality were called into question as fellow feminists lifted her up to prominence as the epitome of Goddess. Look, I’m all for Beyoncé and I used to listen to “Why Don’t You Love Me” on repeat, but her feminism is not everyone’s feminism. Beyoncé is married with a child — married to the man she’s been assumedly exclusively sleeping with and dating for pretty much my entire life. She’s been raising money for feminist causes, reclaiming the movement for women’s social, political, and economic freedom, and penning additions to the Shriver Report in her free time. In terms of the image Beyoncé conjures up in the minds of men and women across the nation, it’s pretty clear that it’s one of moderate respectability and responsibility. Beyoncé is not Nicki Minaj.

Nicki Minaj is not a woman who easily slides into the roles assigned to women in her industry or elsewhere. She’s not polished, she’s not concerned with her reputation, and she’s certainly not fighting for equality among mainstream second-wave feminists. She’s something else, and she’s something equally worth giving credence to: a boundary-breaker, a nasty bitch, a self-proclaimed queen, a self-determined and self-made artist. She’s one of the boys, and she does it with the intent to subvert what it means. She sings about sexy women, about fucking around with different men. She raps about racing ahead in the game, imagines up her own strings of accolades, and rolls with a rap family notorious for dirty rhymes, foul mouths, and disregard for authority and hegemony. While Beyoncé has expanded feminist discourse by reveling in her role as a mother and wife while also fighting for women’s rights, Minaj has been showing her teeth in her climb to the top of a male-dominated genre. Both, in the process, have expanded our society’s idea of what an empowered women looks like — but Minaj’s feminist credentials still frequently come under fire.

To me, it seems like a clear-cut case of respectability politics and mainstreaming of the feminist movement: while feminist writers raved over Beyoncé’s latest album and the undertones of sexuality and empowerment that came with it, many have questioned Minaj’s decisions over the years to subvert beauty norms using her own body, graphically talk dirty in her work, and occasionally declare herself dominant in discourse about other women. (All of these areas of concern, however, didn’t seem to come into play when Queen Bey did the same.) Minaj’s perspective has always been multi-dimensional; she comes forward as an immigrant, as a black woman, as a female rapper, as a sexual being, as an artist, as a storyteller, as a survivor, as a bad bitch. She comes forward in order to tell her own story, be it one of domination or declaration. Minaj has even come forward as a feminist. She’s actually done it over and over again. And yet, instead of simply embracing her own discourse on the topic, feminists often can’t wrap their heads around it.

I’m not here to pit Beyoncé and Minaj against one another, of course. I love them both. But it frustrates me that feminists can so obliviously overlook a perspective rooted in self-determination, and it grates on me because the reason is rooted in respectability politics.

“Anaconda” was praised for being a track that both reclaimed the gaze-inspired “Baby Got Back” and also for reversing the narrative of human sexuality in which women’s bodies are worthy of appreciation only when they please men. And when the “Anaconda” album artwork premiered online, feminists were quick to claim the Minaj ass-shot heard ’round the world as revolutionary, despite much debate over how the image of her behind played into the male gaze.  “Whenever black women own their sense of sexuality and it appears to not be controlled by the hetero-male gaze, the whole world gets into a tizzy,” Feministing writer Mychal Denzel Smith wrote. He continued, “If black women aren’t allowed to own their sexuality, then who does it belong to?” What his piece touches on is the ways in which women, and black women especially, are often criticized for expressing themselves sexually despite the repression those expressions fight with every inch of skin. To say Nicki Minaj is modest would be a damndable lie; Minaj has been scantily clad and sexual since the beginning. But are any of us modest? When I put on a short skirt or a crop top, I do so outside of the male gaze, and I am not alone. Women who choose to express their sexuality are not contractually obligated to do so in line with the male gaze, and Minaj’s own choices often call that gaze into question. The integral spirit of defiance that exists within Minaj’s self-imagery is undeniable. The perfect example of this defiance is the video for “Lookin’ Ass,” in which Minaj poses in a revealing outfit while literally destroying the male gaze.

“Whenever black women own their sense of sexuality and it appears to not be controlled by the hetero-male gaze, the whole world gets into a tizzy,” Feministing writer Mychal Denzel Smith wrote. He continued, “If black women aren’t allowed to own their sexuality, then who does it belong to?” What his piece touches on is the ways in which women, and black women especially, are often criticized for expressing themselves sexually despite the repression those expressions fight with every inch of skin. To say Nicki Minaj is modest would be a damndable lie; Minaj has been scantily clad and sexual since the beginning. But are any of us modest? When I put on a short skirt or a crop top, I do so outside of the male gaze, and I am not alone. Women who choose to express their sexuality are not contractually obligated to do so in line with the male gaze, and Minaj’s own choices often call that gaze into question. The integral spirit of defiance that exists within Minaj’s self-imagery is undeniable. The perfect example of this defiance is the video for “Lookin’ Ass,” in which Minaj poses in a revealing outfit while literally destroying the male gaze.

Minaj also frequently juxtaposes sexualized imagery with lyrics about her own sexual desires or the men she is accepting — or, frequently, rejecting — as partners. In Big Sean’s “A$$,” which was literally about men appreciating women’s rear ends, Minaj questions Big Sean’s own endowments. “He like it when I get drunk, But I like it when he be sober,” she tells us in “High School.” In “Barbie World,” she remarks: “Yes, sir, I am that bitch. Fuck you silly like the rabbit,” right before giggling. These lyrical decisions make it clear that she exudes sexual desire, not sexual availability. She owns and defines her own sexuality, time and time again — be it in conjunction with or in opposition to the desires of men, desires which she repeatedly calls into question. And when feminists make the mistake of questioning Minaj’s depiction of her own sexuality, they fall into oppressive and problematic matrixes which situate sexual pleasure as antithetical to self-respect or empowerment. This is what brings me to the latest feminist point of contention in Minaj’s career: her lap-dance with Drake in “Anaconda.”

“The song ‘Anaconda’ is a bold, sex-positive statement about a woman’s ability to own her own body and sexuality. The video, though, completely fails to follow through on the song’s potential for a powerful feminist message, instead relying on the tired trope of hypersexualizing women’s bodies,” Sophie Kleeman wrote for Mic when the video dropped online. “It opens with Minaj and a gaggle of backup dancers in a jungle setting, writhing and sweaty as they grind against the ground and each other. It also features Minaj in a kitchen, chomping down on a banana and covering herself with whipped cream. Drake also makes an appearance — but only as a prop for a lap dance during which, as Gawker informed us, he got a ‘boner.’ This maybe doesn’t count as empowering anyone except Drake.”

What Kleeman misses in this analysis, however, is critical. Drake’s own sexual pleasure has nothing to do with that lap dance, and his “hover hand” says it all. Throughout the lap-dance montage, Drake sits absolutely still, unpermitted by Minaj to touch her at all as she gyrates and grinds on and near his body. As Kevin O’Keefe wrote for The Wire, “He’s just here to experience Nicki’s butt.”

Throughout that lap dance, Minaj is the one in control, and she’s acting on her own sexual desires. She’s simply expressing her sexual desire. Her lap dance is an act of seduction, not of submission. So is the rest of the ass-slapping, ass-sliding, ass-centric hot mess of a video. Making a video about her own ass might seem contradictory to the values of feminism, but if you take a closer look, it’s happening outside of and in defiance of the ideal beauty standards that hold women down and the male gaze that controls their bodies.

As Lindsay Zoladz wrote for Vulture:

Plenty of people — prominent among them, Nicki Minaj — are happy to talk about Nicki Minaj’s ass, but fewer want to confront a certain sense of unease that she creates in her most provocative videos, like the stark, black-and-white clip for the 2014 single “Lookin’ Ass” (in which she quite literally guns down the male viewer) or her great 2012 collaboration with Cassie, “The Boys” (which plays out like a candy-store-hued pop-art Thelma & Louise). And it’s there in “Anaconda” too. These videos enact a certain bait-and-switch violence toward the viewer who has the audacity to think Nicki is shaking her ass for him; they draw you in with their neon-bright, sexually charged imagery, and then they suddenly, unexpectedly turn confrontational.

It isn’t the male gaze, dominant narratives of sexuality, or hegemonic femininity which reigns true throughout Minaj’s work. It’s her own sexual state of being. And when Nicki Minaj struts out in a string bikini or exudes her own sexuality in the middle of something otherwise empowering, it isn’t an inherent contradiction or a cause for debate. It’s simply a reflection of how many women — women who, often, feel comfortable with and empowered in their choices — are living their sexual lives. As sexual beings, we’re allowed to indulge in self-directed pursuits of pleasure without shame. We’re allowed to be frank about our own exploits. We’re feminists who fuck, and a lot of times it looks like both things happening at the exact same time. That’s what central to the revolutionary aspect of Minaj’s work: She’s never been shy about her own sexuality, nor has she been subtle or polite about it. Her lyricism has been consistently vulgar, shocking, and delightful — and often, has embraced a more realistic narrative about sex than songs which describe it using only metaphor. Whereas Beyoncé might say “it’s sweetest in the middle,” Minaj is more likely to say, “I let him play with my pussy then lick it off of his fingers.” Same sentiment, but with a much different place in the matrix of respectability politics, gender politics, and mainstream music.

“Anaconda” wasn’t an isolated incident, and it wasn’t Minaj’s first time articulating her own identity nor her last. Throughout her feminist declarations, however, has appeared the same specter of doubt. Feminists refuse to take Minaj’s statements seriously, continuously torn between embracing her sexually raw and eccentric persona with her own self-declared girl-power focus. It’s clear that when Minaj is making feminist statements in a language that resembles mainstream feminist discourse, folks are giddy to jump on the bandwagon — but her oversexualized state of being, her sexual aggression and occasional sexual dominance, often worry them. This is hugely problematic. It’s the impossibility of ultimately marrying the image of a sexually empowered woman to her state of existence which allows for the distorted view of women’s sexuality to prosper. When feminists honor Minaj’s feminist lyrics, as they did with “Anaconda,” and then admonish her for expressing herself with sexually charged images and videos, they are playing into the same dominant narratives about women’s sexualities that perpetuate victim-blaming, slut-shaming, and the subordination of women.

Despite the debates over “Anaconda,” Minaj remains one of the few artist willing to explicitly confront the gender parsing that puts pressure on her career every day, be it in music or in interviews. Early on, Minaj declared herself apart from the other, more submissive girls of the world. She declared her intent to “Go Hard.” She was open in her own self-doubt on “Can Anyone Hear Me?,” articulating her desire to stay true to herself as she progressed as an artist. She spoke out about her intent to make room for other women in rap in “Still I Rise.” In “Here I Am,” she describes an abusive relationship — and articulates her own self-worth as she breaks free from it. She spoke frankly about her power to represent unseen and unheard voices in popular music in “I’m the Best.” In “Fly,” she spoke about breaking out of the constraints placed on her in her industry. She partook in some navel-gazing on “Dear Old Nicki,” publicly lauding and embracing the rap persona she’d presumably laid to rest since hitting the mainstream in a brave act of self-acceptance. She compared herself to Marilyn Monroe in a track named after the starlet herself, admitting both her faults and her own self-determined self-worth. She “Endorse[d] These Strippers.” She sang about being the shit with Ciara on “I’m Legit.” The proof is in the pudding, respectability politics be damned.

Nicki Minaj is a feminist, and she expresses that in her work. In the long run, what Minaj has contributed to the existing and ongoing dialogue of women’s oppression is the perspective of someone who refuses to be defined by any categories she doesn’t claim for herself or constrained by the desires of other people. Today’s feminist blogosphere can get super hung up on who self-identifies as a feminist and who should be allowed to, but what that conversation ignores are both the variances among us as women and the real, lived experiences of women living in those variances. In a universe in which we are still enslaved to the dichotomy of “slut” or “virgin,” Nicki Minaj has chosen to live within her own spectrum of sexual expression — and she’s proven that at no matter where we land on that spectrum ourselves, we’re still whoever we damn well please, feminism and all.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: All credit for the phrase “Hover Hand” should be directed toward Brittani Nichols.