Natural Hair Was My Final Frontier to Self-Love as a Black Trans Woman

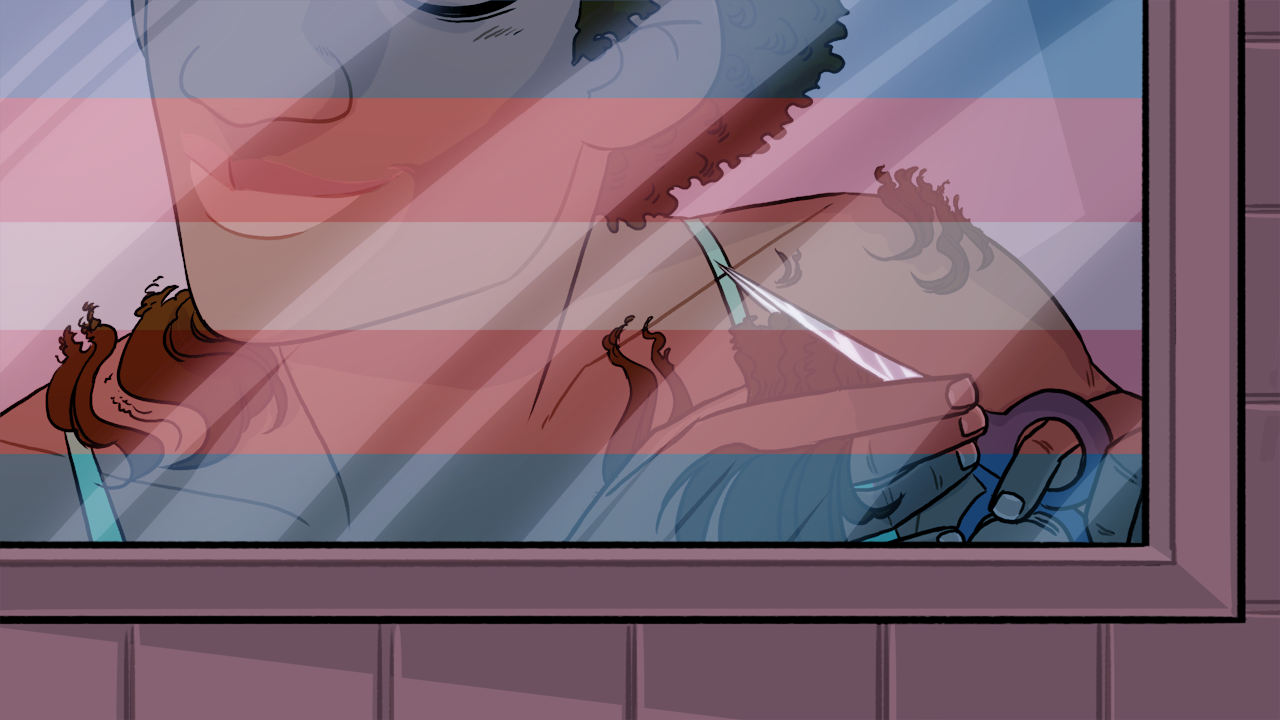

illustration by Mildred Louis

“He [Tea Cake] drifted off into sleep and Janie looked down on him and felt a self-crushing love. So her soul crawled out from its hiding place” (Hurston, 122).

Since reading Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God the second semester of my eighth grade school year in Tracy Kukwas’ creative literature class, I can recall a yearning for something, someone, or a moment that would make my soul “crawl out of its hiding place” and watch God.

I took my obsession with Zora Neale Hurston’s book to another level by watching the movie starring Halle Berry. At the beginning of the movie, the sassy main character Janie proclaims, “there is two things people have to learn for themselves; love and how to live.” In my early twenties, I couldn’t agree more. What had seemed impossible — living as a trans woman of color — had seemingly become easier. I began to accept the destiny God and the higher power ordained for me. I was “learning to live,” as Janie put it. However, my self-revelation didn’t equate to love. Just because I’d finally accepted myself didn’t mean I loved what I accepted. After years of self-analyzing and mediation I had oddly narrowed my annoyances with myself down to one thing… my hair.

During my early mornings of meditation I flashed back to countless hours and dollars spent in the hair salon straightening my hair to the point of overmanipulation in an attempt to fit the Eurocentric mold. As a child, I never saw an example of a black woman with natural hair. My mother, my sisters and I all hot combed, pressed and even chemically relaxed our naturally curly strands. I realized my identity at a young age and, consequently, unknowingly conflated my trans identity and my idea of femininity with “having straight hair.” If it wasn’t straight, it wasn’t right. If it wasn’t flat, take it back. This equation would prove to be problematic in my later years.

Let the fight within begin! Even after narrowing my problems with myself down to “my hair,” it still felt like putting boxing gloves on every morning to tackle the tedious and time-consuming chore that was my hair. It was like I was allowing myself to sink further into a self-loathing hole. I continued hating myself and, as a result, hated every man I encountered. I went on countless dates with plenty of bachelors but I still couldn’t shake the feeling of being uncomfortable. I struggled with feeling my sense of self. My “crown of glory,” as the Bible so eloquently refers to a woman’s hair, was so fried and damaged that I’d resorted to wearing full wigs in an attempt to mask the natural part of me that I’d grown uncomfortable with.

“Salon Saturdays” were my mom and older sister’s day of feminine relaxation; it was a “no boys allowed” sanctuary. Once I started growing my natural hair long I was honored (and forced by my mother) to be asked to join them on early Saturday morning excursions to my Aunt Lisa’s hair salon. The hair salon was the polar opposite of the barbershop; at my Aunt Lisa’s we didn’t discuss our anticipation for Sunday’s game or bore one another with meaningless mechanic talk. No no dear, we made things happen. The salon was where so many little girls found themselves: it was prom talk, wedding jitters, feminine sugar, and so much sass that the meanest most masculine giant would be desperate to find peace. The salon was full of “grown girls,” as my mom put it, and I more than anything yearned to belong.

My aunt’s salon represented my stepping over the threshold to “girl world.” It was in those early Saturday morning conversations between women old and young that I learned what a woman was To Be and Not To Be. It was there that I eavesdropped on my first-ever conversation pertaining to natural versus relaxed hair. My aunt Lisa’s voice startled me from my daydream; “Oh hell nah!” she shrieked, “God ain’t got time for nappy hair and neither does Lisa Lilly!” My adolescent eyes soaked in my aunt Lisa turning away a “nappy-headed” customer because she didn’t off her services to natural clients. Everyone, including my sisters, struggled to contain their laughs after the woman turned around and stormed out the door. The “nappy-headed” stranger had become the laughingstock of Lisa’s Ladies Salon. Before this event, I’d seen nothing wrong with my hair when it wasn’t hot combed. My curls were fine, I thought. So why had Aunt Lisa turned the woman away for having hair that looked like mine did before hot-combing? That moment was pivotal. It shaped how I felt about my natural curls. I didn’t want Aunt Lisa or any of the girls in my most important feminine sanctuary laughing at me or calling me “nappy-headed”! From that day forward I vowed to press, comb, iron, steam, relax and even burn my hair to prevent any forms of nappy.

After more than two years and what seemed like one hundred failed relationships due to my insecurities, I stood in the mirror with my scissors in hand. I don’t know what came over me, I was a woman possessed. I silenced the hectic Atlanta traffic bleeding through my window. I inhaled. I exhaled.

I began cutting.

I cut and I cried, tears falling to the floor along with the strands of my damaged locks.

Illustration by Mildred Louis.

After removing my damaged locks, I realized that physical removal was the easy part. Removing the Eurocentric straight- haired image of femininity embedded in my brain was much harder. I struggled every day after cutting my hair. Every day seemed like a test from the self-love Gods; especially when I’d become envious passing a beautiful woman of color whose natural hair fell past her shoulders. My natural hair journey began just shy of a year ago. It’s hard to believe that almost one year ago I stood in front of a mirror and did what most little black girls would cry to do. I removed the chemically relaxed ends from my hair and embraced me. For the first time in nearly 21 years, my soul crept out of its hiding place, and with time I loved what I saw.

As I’ve grown I’ve found more femininity in my curly ringlets than the lifeless and flat weave, wigs and braids that adorned my head prior to transitioning (the process of removing the chemically altered strands of hair from your hair). Today my hormone replacement transition correlates with my journey and transition to natural hair. These things make up my blackness, uniqueness, womaness, and my me-ness. It wasn’t until recently while attending a course on my HBCU campus that I looked around and saw many black girls like myself — I saw curls, ringlets, puffs, and coils adorning the head of hundreds of little black girls. I looked up to heaven and smiled. I thanked God for blessing me with such beautiful reflections of myself and my journey. I mentally welcomed these girls into my girl sanctuary. I thanked Her for allowing the souls of so many black girls to creep out of their hiding place and watch God.