My Trans Body as a State of Desire

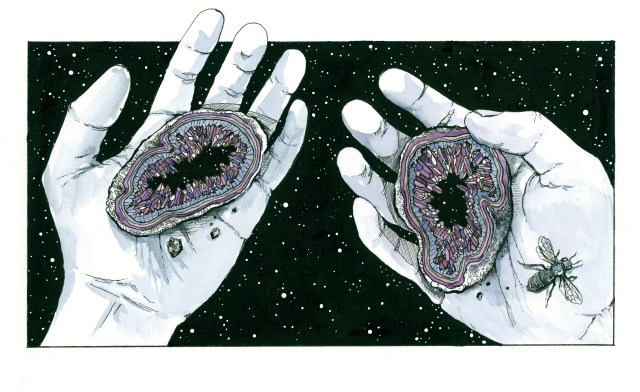

Feature illustration by Sophie Argetsinger

I was 14 the first time I accessed information about hormone replacement therapy online. I may have taken 13 years to do anything concrete with that knowledge, but it represented a shift in my thinking about “becoming” a girl. For so long, it’d been a thing I’d wished or prayed for, a thing that kept me awake or made me sob into my pillow at night as I learned first-hand the effects of testosterone upon my body. There was a science to the change I wanted, something no less magical because it could be applied topically or ingested or injected. There was a short list of the things hormone replacement therapy could do for me.

Illustration by Sophie Argetsinger

One of the first and most prominent of the changes listed on the website was that an estrogen regimen would significantly lower my sex drive. At 14, this didn’t matter. At 17, this didn’t matter. At 20. At 25. The science was real, but the reality of transitioning was as abstract to me then as it is viscerally present now. What did it mean that estrogen would lower my sex drive? What did it matter as a woman who had no access to the hormone? I watched my body continue to change as I sought refuge from depression in food and booze, as my hair began to thin out, as my beard filled in. It would be generous to say that my libido was lower-than-average. I hated my body and, even more than that, hated the idea of sharing it with another person.

Still, I kept reading about hormone replacement therapy. Resources were still scant. As such, the effects of hormone replacement therapy listed on every site I visited, whether they were written by trained medical professionals or other trans women, all began with the same thing: You’ll notice that your sex drive is lower. You’ll notice it quickly. You’ll need to adjust. This is a rather phallocentric notion of libido, one measured in erections and little else. But it makes sense, thinking about how we use phrases like “achieving an erection.” What a sad thing, the lack of achievement.

Is it hard to get hard now? Yes, but I’m not here to mourn the loss of my boner. My penis is still there, still responsive, a bundle of nerves and flesh and blood that is stiff when it’s stiff, and otherwise soft. Like it was before hormones, just not as present. The physical reality of my penis honestly isn’t something I’ve thought about much since I started transitioning. I’m interested in other things that are happening to my body. It’s taken me 27 years to appreciate the nipple. I’ve never quite had the same experience of smell as I do right now. And, sister: Feelings. In all their fullness. Razor sharp. Crystal clear. Deeply felt. This is the change I am most taken by. Before estrogen I was a nervous person huddled by a dying fire in the mouth of a cave I was too afraid to explore. Now that I’m six months in on a process that will take the rest of my life, I’m only just realizing how vast and intricate my emotional cavern is.

Right now, I inhabit the notion of desire. Here is a word I’m having trouble with, an idea, an emotional state of being. Here is a word that I believe lies beyond the idea that hormone replacement therapy blunts a person’s libido. Here is a word that works differently for me now than it has in the past. A word that is both more and less capable than several others: Attraction, longing, passion, amorousness — nothing here is dulled. My brain is lit like the map of a major metropolis at night. My body is, too. “I am at one with a sea of sensations, glitter, silk, skin, eyes, mouths, desire,” Anaïs Nin wrote, and that’s pretty much it. Or, put another way: I have found an affirmation of selfhood, and I haven’t thought to immediately annul it.

That’s where this newfound means of experiencing desire comes from, I think. My skin. My eyes. My mouth. When I look at pictures of me taken six months ago, another life ago, I don’t recognize these things as mine. They belonged to somebody else. Somebody I loved. Somebody I hated being. It seems strange to me now that I could house those two things simultaneously. When a person looks at me and thinks about how I look now as compared to how I looked then, it usually comes back that I look happy, happier now, at least, than I was then, when I loved and hated life. What changed, beyond the obvious? I wonder that, too. And I think the answer is desire, which is a phenomenon I am capable of observing much more carefully now than I was in the past. I am thinking of self-love and self-hate as two wavelengths, only, for me, both were constantly peaking at the same time. Hormones have set those wavelengths oscillating again. They peak. They valley. They meet. They diverge. Sometimes I think desire is what sets them in motion. Sometimes I think desire is when they meet. Sometimes it’s as if desire is all I know. Sometimes I wonder if I know it at all. But the wavelengths play out, into their uncertain future, and that, I know, is where this emotion really lives, a place I cannot see.

I’m thinking of my body as the state of desire, how it is here and present, and how its home, too, is the future. Transitioning is, in addition to all the other things it is, an act of patience. Think of how young many trans and gender non-conforming people are when they know. Think of the long space that frequently exists between that discovery and the next, the idea that something can be done. And then the space between that discovery and action, whatever action means. For me, action is hormone replacement theory. For me, patience is acceptance that this treatment is not instantaneous, that, like many things, it takes time for change to be evident to those who aren’t looking for it. That, for me, who looks for change every day, change is often invisible. I’m thinking of how frustrating desire often is. How it often takes the form of infatuation. I am infatuated with my changing body. I am infatuated with other bodies. My eyes register both. My skin feels both. My mouth, however, cannot articulate either desire. Perhaps my mouth belongs to the future, too. Perhaps this essay.

But I have to think of myself as I am now. I can’t stand to think of myself as waiting. I can’t stand to think of myself as in-progress. So I think of myself as desire because I think of desire as a thing that lives in me now and will continue to live beyond this vessel. It’s hard for me to imagine desire as a thing that can be dulled be estrogen, but it is something I experience differently. I am in the cavern, navigating by torchlight. The cavern isn’t alien, but it is different enough that to call it so wouldn’t be unfair. Somewhere, in a recess I’ve yet to explore, there is something calling to me. Right now, it registers as a whisper, but the closer I get the more I can hear. I go deeper into the cavern. I take the persons I have been with me. I want us all to experience this music.