More Than Words: On the Word “Gay” and Definitive Dilemmas

Welcome to the twenty-fourth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

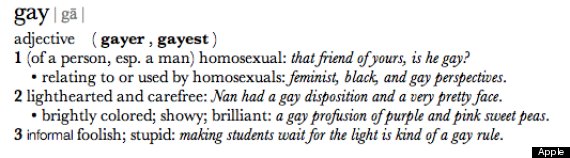

This past week, high school sophomore Becca Gorman made news when she looked up “gay” in her Macbook Pro dictionary and found, alongside the two entries she expected, something that surprised her:

SWEET PEAS!!??!

Gorman, who was doing a school project about LGBT rights, searched around to see if this was normal practice. When she didn’t find this “informal” definition in any other dictionary, she sent an email to Apple CEO Tim Cook asking him to change the definition to avoid “normaliz[ing] the terrible derogatory twist that many people put on the word ‘gay,'” or at least to “note in the context that it’s a pejorative expression.”An hour later, a representative from Apple called her house, telling Gorman that they too were “shocked,” that it’s hard to track exactly where their definitions come from, and that they’d remove it ASAP. As of Monday afternoon, some versions of the Apple dictionary still include the third definition (some include the caveat “often offensive”, while others leave out the “informal”). MK over at Youth Allies did a roundup of other LGBT-related Apple dictionary entries that might benefit from some context.

There are some unalienable truths about this story: Becca Gorman is way more badass than I was at fifteen, the word “homosexual” sounds weird to me all the time, and whoever’s being quoted in that example should be made to wait for the light forever, as he or she is clearly far from it. The immediate solution to this particular problem is technical and can be solved by a software update: Apple licenses their dictionary entries from the New Oxford American Dictionary, which, like any good dictionary, is constantly reworking itself. People using old software may be stuck in a time before New Oxford figured out that that usage of “gay” is a slur and should be marked, as is their particular custom, “offensive” or “derogatory.”

DON’T BETRAY YOUR ROOTS, APPLE

Apple should make sure this fix happens. As supposed arbiters of concise correctness, dictionaries hold immense cultural power. This is attested by Frindle, as well as many great jokes (did you know that “gullible” isn’t in any dictionary at all? I swear it’s true! Look it up if you don’t believe me). This isn’t the first time that a movement has tried to harness this power by taking matters into their own hands. Since July, a group called HACKMarriage has been providing printable stickers with a succinct, gender-nonspecific definition of marriage, as well as hosting “dictionary hacks” where groups of volunteers stick these new definitions over the existing ones. “We decided to speed things up by hacking the institution that literally provides meaning to our lives: the dictionary,” they told the press. “Because when our definitions change, we change. As a people, as a culture, as a society.”

A MODERN CLASSIC

But is that really how it works? When we, as a culture, begin using a word differently, do we do so first within the reference books we check to help us live our lives, or in the everyday lives that those books supposedly reference? It’s a chicken-egg question, but it’s also an issue that has divided dictionary-makers for decades — since way back in 1961, when the third edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary was released. Webster’s Third, as it’s now affectionately called, was the first controversial modern dictionary; it was nearly universally panned, described as “subversive” and “permissive,” and “a scandal and a disaster,” and nearly bankrupted its publisher. Why? Because it included “all the words, whether good or bad,” including such pearl-clutchers as “ain’t” and “kleenex.” By asserting that “the basic responsibility of a dictionary is to record language, not set its style,” editor Philip Gove invented a philosophy for observe-and-report-style dictionary-makers, or “descriptivists,” that stuck. He also inspired the rise of an opposite camp, the study-and-instruct-style dictionary-makers, or “prescriptivists,” who believe the basic responsibility of a dictionary is the opposite — to decide what is proper and correct in language, encourage its use, and discourage everything else.

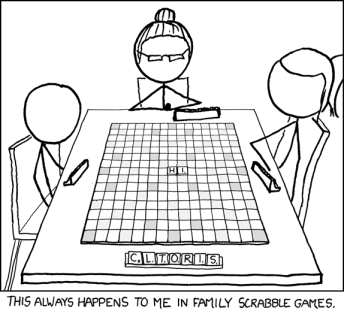

In the sprawling book-review-gone-wrong “Authority and American Usage,” David Foster Wallace aligns prescriptivist and descriptivist philosophies with political ideologies: “[Much of] pop prescriptivism just sounds like old men grumbling about the vulgarity of modern mores… for another thing, the very language in which today’s socialist, feminist, minority, gay, and environmental movements frame their sides of political debates is informed by the descriptivist belief” that the “rules” of language were invented by, and best serve, those who happen to already have social influence, and that a truly democratic dictionary would not include them. (Viewed in this light, Scrabble fights seem more ominous.)

via xkcd

I happen to have a few of prescriptivist guides — when my grandfather found out I wanted to “take up the pen” (his words) I inherited a stack “in order to do it properly” (those too). I flipped through Paradigms Lost: Reflections on Literacy and Its Decline, a 1980 lament by the critic John Simon, and came upon an entry I hadn’t noticed before:

“The special-interest use of gay undermines the correct use of a legitimate and needed English word. It now becomes ambiguous to call a cheerful person or thing gay; to wish someone a gay journey or holiday, for example, may have totally uncalled for over- and undertones and, in conservative circles, may even be considered insulting. The insulting aspect we can eventually get rid of; the ambiguous, never. What do we do about it? If we energetically reject gay as a legitimate synonym for homosexual, it may not be too late to bury this linguistic abomination.”

Thirty-three years later, Mr. Simon has clearly lost this battle. But it just goes to show that prescriptivism cuts both ways. For every HACKMarriage member amending the dictionary so that the definition of “marriage” reflects the progressive world they’d like to live in soon, there’s a John Simon trying to change things back to the stodgier world they miss. And as imperative as it is to stop it, people still do use “gay” in a derogatory way. If we don’t have a grasp on how things are now, how can we hope to begin making them better? Better to let dictionaries, of all places, keep telling it like it really is.