Low-wage workers in America are finally throwing up their fists.

On Thursday, fast food workers in over 100 cities across the country went on strike for the day to demand a $15 minimum wage, which is over double the nation’s pathetic standing rate of $7.25. They were also protesting for the right to form a union without retaliation, which would put them in a better position to collectively bargain on the local level for protections and wage-related benefits.

The strike echoed this year’s Black Friday protests, in which retail employees from Walmarts took a similar action by staging all-day protests during the country’s biggest spending event of the year. Their demands were along the same lines: a $25,000 yearly salary for all employees, increased ability to work full-time hours, and unionization without resistance.

For employers like McDonald’s and Walmart, the suffering of their lowest-ranking workers doesn’t go unnoticed — nor does it disturb those in higher ranking positions. Managers at a Walmart in Ohio enlisted assistance from fellow workers to help employees make ends meet for Thanksgiving, and McDonalds’ Human Resources Department tells employees to apply for food stamps when they come asking for more hours or higher pay. Walmart employees cut deep into the economy every year because they rely on various form of public assistance.

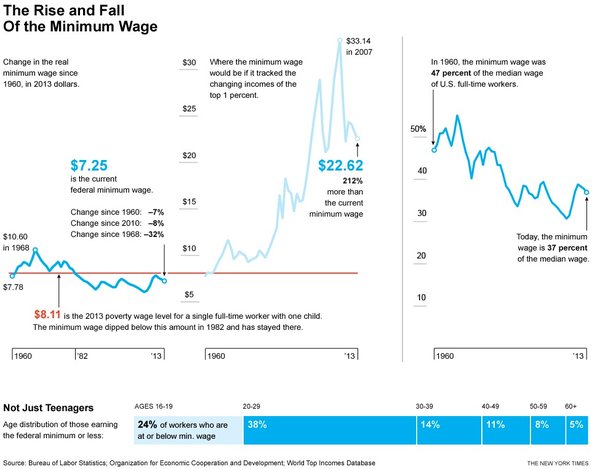

The demands of workers participating in these protests are not so great that their employers can’t commit to them. If McDonalds doubled the wages of everyone they employed — including their multi-million dollar CEO — the price of a Big Mac wouldn’t even increase a dollar, and research shows that Walmart could pay their employees $25,000 per year without raising their prices. (Employers like Costco remains proof that rewarding workers well for their work does no harm to corporate growth or morale — and indeed often does the opposite.) Economic data has also shown that these workers are fighting for something which has been theirs all along: if low-wage salaries had remained consistent with the earnings of America’s top 1% since its creation, every minimum wage worker would be making over three times the current federal minimum wage. Instead, they’ve been earning poverty wages since 1982. Raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would lift over 3.5 million people of color out of poverty.

President Obama has come out in support of a $10 minimum wage, and he spoke out recently and labeled income inequality “the defining challenge of our time.” In his speech, he added: “We have to reject a politics that suggests any effort to address [income inequality] in a meaningful way somehow pits the interests of a deserving middle class against those of an undeserving poor in search of handouts.”

A demand for a $15 minimum wage proves that these shows of interstate worker solidarity and a move toward unionizing and finding success within the community of working-class America proves that this is about more than a federally-decided standard for baseline pay. This is the beginning of a war on an economy that makes certain people vulnerable so a select few can survive.

Many of the people affected by minimum wage legislation and the working conditions in low-wage positions are women, people of color, immigrants, young people, and displaced workers from other sectors which fell apart in the recession. In other words, a lot of them look like you, the people you love, and the people you’ve been fighting for.

https://twitter.com/Fightfor15LA/status/408692748686852096

A majority of minimum wage workers are young women employed in the service sector. In the fast food industry, 73%of all front-line workers are women, and 43% are African-American or Latina. A recent Ms. magazine feature on women in the fast food strikes illustrated that for women workers, chances at advancement remain incredibly low — as they do across all sectors and industries — compared to that of their male counterparts, although the opportunities for advancement for all fast food workers are low. Only 2% of fast food employees are managers, and less than 10% are supervisors. In many ways, the service industry is attacking women and, therefore, families by keeping them in the lowest-paid positions and thus replicating the feminization of poverty we see around the world. But what’s happening behind the scenes to keep women down is now resulting in a massive number of women coming out to demand justice. A feminization of poverty has become the feminization of activism.

“When I spoke at the rally today, I wanted to remind people that women still make less wages for the exact same job as men do, and I also wanted to remind people that the Senate recently passed ENDA,” trans* protestor and journalist Ashley Love told Autostraddle Contributing Editor Laura Mandanas at the Zucotti Park rally. “I was very upset because at least 20 speakers had spoken and not one of them mentioned gender inequality, and not one talked about discrimination against LGBT Americans in the workplace.” Love said her experience of demanding the opportunity to raise these issues was a reminder that “even we in the 98% don’t always like to talk about sexism.”

Willieta Dukes, a Durham, NC Burger King guest ambassador, told Ms. that she considers the fight for worker’s rights an essential piece of the movement for women’s rights. “We’re the ones on the front lines,” she told writer Michelle Chen. “We’re the ones on the back lines. But the men sit in their office. They do the paperwork. They run around in their big cars to get their bonuses… We deserve more as women and mothers and as workers.”

Indeed, it is women who are living at the intersections of workplace discrimination and wage inequality when they come to work each morning who are now bringing this movement to its apex. As I’ve written about previously, the folks living at intersections feel all of the effects of inequality once, twice, or three times over — often manifesting as a lifelong series of obstacles that hinder their chances at basic human survival. For women, people of color, immigrants, and gender-nonconforming and/or trans* folks, the effect of income inequality low-wage workers have been protesting compound and play into one another to make the effects of inequity even more inescapable.

“I came out today,” Occupy Wall Street veteran Athena told Mandanas, “because we can all create so much beauty that it will infiltrate through the world.” She added:

The fast food workers today are being very brave and they are coming forward like many other works are, and I think that the way that different groups are coming forward shows any other group that they can, too — like we did today — we come together and then we realize that we are together, that we do have the power. So I’m thrilled that the fast food workers are striking and I think it just encourages more fighting for what we all deserve.

Gina Chiala, a Stand Up KC spokesperson, echoed those sentiments to Ms. Thursday. “So many workers and organizations know that if we don’t change the trajectory in this country toward poverty wages and industries that make billions of dollars, the gap between the rich and poor is just going to grow,” she said.

A demand for a living wage moves the labor rights movement for low-wage workers beyond the concept of “scraping by” and toward a concept of actual economic justice for all people. Economic justice for these women isn’t about simply making “enough money to live,” which isn’t even a baseline that their jobs are currently meeting, but about moving further past that to a place of access, opportunity, and advancement. Economic justice is being able to dream with your money. Being able to eat and feel full with your money. Being able to clothe and house your family — no matter its size — without feeling shame, guilt, or anxiety. The concept of a “minimum wage” is the problem is the equation, not the solution: by designating a literal floor for wages, a mark at which only living below is labeled as problematic and not subsisting in stasis with, we both lend shame and deny dignity to the folks earning anything near it, and we allow it to become associated with work that we, as a culture, have agreed deserves to remain there: service jobs. Food service, hotel service, wait service, cleaning service, secretarial service.

No matter your educational experience or your life situation, you deserve to make enough money by working to survive in America. By setting the standard of a living wage — by raising the bar for employers and challenging our culture’s notion of what “a part-time worker” looks like and “needs” from their salary — we make America’s economic system work better for everyone. Most American families currently earn under $60,000 a year, and wage penalties for women related to their family life, gender presentation, sexual orientation, race, and sex still persist in America’s workplaces. When we allow any worker to be exploited, harassed, and robbed of their opportunities, we open the door for the effects of that treatment to move up and beyond their sector, beyond their industry, and beyond their life experiences. When we treat low-wage workers like they’re not fully human — which is already inexcusable — we suggest that we can get away with treating middle-wage workers like they aren’t fully human. And so it goes. This is everybody’s fight.

Two solutions to the problems being laid out by workers are being discussed during reporting on the strikes: the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2013, which raises the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour by 2015 and adjusts automatically with cost of living, and more local, hands-on organizing and unionizing work for gradual, worker-controlled workplace protections and wage adjustments state-by-state. Neither solution is perfect: the FMWA doesn’t account for the true cost of living, even as it raises the minimum wage by almost three dollars per hour, and the solution of letting workers stand up for themselves would ultimately lead to awesome workplaces but, in the meantime, still leaves them with no recourse or solution. A hybrid of both would be best: setting a livable standard and allowing workers to unionize and work together for more specific needs that may not be generally applicable to their industries. (With a Congress which makes “passing a bill” the new “creating matter out of nothingness as contrary to all scientific data,” this is all more of a fantasy than an impending reality, anyway.)

As low-wage workers fight for their ability to survive, it becomes more imperative that we find an ideal solution – and that nothing less will fix the economic structures we’re all struggling with each day.