feature image via facebook

Who cares, right? Some stupid festival. Except this thing happens where I meet somebody who seems like a cool queer, talk to them for a while, find out eventually that they go to Michfest, and end up realizing: I cannot trust anyone. Nobody has to be accountable to trans women about this shit anywhere, ever. It is this insidious thing that sneaks up on you every time you go to a party or a reading or something: one of these queers to whom I’ve just been introduced goes to Michfest. I mean, I think it is clear how that would make a trans woman feel fucked up, right? “Oh yeah I am good friends with someone who spends hundreds of dollars every summer to support a group that defines ‘woman’ as ‘not you.’”

I was 15 when my Mom told me about The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. She was going, obviously, with a group of her lesbian friends, and she said I too would love Michfest and I’m sure I said something snarky and awful about how unlikely it seemed that she and I could possibly enjoy the same music festival. I was 20 when a group of old friends who’d recently come out invited me to Michfest, probably the same summer I accompanied my frat boy boyfriend to Warped Tour, and I declined. Like most things I said “no” to back then, eventually coming to terms with my own sexuality would transform my feelings on the matter-at-hand into a rousing HELL YES.

But I didn’t live in Michigan anymore, and despite my love of “women’s music” and curiosity about this hippie Disneyland it was difficult to justify the expense — so I should’ve jumped at the chance to attend when Autostraddle was offered press passes last summer. But between 2005 (when I added it to the bucket list) and 2013 (when we were invited), I stopped wanting to go altogether. And I’m not the only one.

There are thousands of women just like me who weren’t at Michfest last week for reasons that are more ideological than practical (although there is that, too). Because somewhere between my Mom’s generation and my own, Michfest stopped being known as a place to celebrate diverse womynhood and became an institution synonymous with transmisogyny and discrimination for its trans-female-exclusionary “womyn-born-womyn” intention. Furthermore, this “intention” and the controversy surrounding it have become a stain on the entire lesbian feminist community. Every summer, vicious infighting erupts around the artists who are performing at Festival, draining energy and severing unity amongst the very community Michfest claims to celebrate.

This year, activists and performers weren’t the only ones who are speaking out against the intention. Two weeks ago, Equality Michigan launched a petition calling for Michfest to put an end to it, and The Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBT civil rights advocacy group and political lobbying organization in the country, announced that they “stand in solidarity” with Equality Michigan, stating, “While the organizers continue to insist that excluding trans women is not an official policy, their “intention” that the festival caters exclusively to “womyn born womyn” serves to further marginalize trans women, denying them access to one of the only exclusively female spaces in our society.” On August 4th, The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force signed the Equality Michigan petition and announced their solidarity with the position.

In response, Michfest posted a statement on their Facebook page characterizing Equality Michigan’s stance as “based on misrepresentations, purposeful omissions, and selective editing of prior Festival statements on this issue” and argued the following:

The experience of being female, like the experience of being trans, informs how we become the womyn we are. Recognizing the inherent differences in these overarching experiences is the true meaning of intersectionality. Gathering around these particular strands of experience is no more discriminatory than womyn from the continent of Africa gathering without African-American womyn, womyn from the U.S. South gathering without womyn from the Pacific Northwest, or working class womyn gathering separately from womyn with class privilege. All of our oppressions are real. To create a hierarchy of oppression that disappears any groups’ experience sets us one against the other.

Considering declining attendance and an increasingly shorter list of people willing to perform at Michfest, it seems like any year now could be Michfest’s very last chance to get its shit together. But if herstory is any indicator, it’s more likely the festival will disappear altogether than change its exclusionary ways — and that’s either unfortunate or passively inevitable, depending on who you ask.

“The Festival has lost an entire generation of women through sheer stubbornness and refusal to move forward with the times,” Bryn Kelly, a transgender writer and performer who attended Michfest in 2008, told me. “What used to be a symbol of feminist liberation has now become a symbol of transgender oppression. At this point, Festival’s WBW intention has lasted longer than the US Military’s Don’t-Ask-Don’t Tell policy. I don’t believe they’ll ever recover from this decades-long public relations debacle.”

Others are holding out hope. Trans activist Kayley Whalen, Executive Office Board Liaison at the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, wrote about her Michfest experience for The Huffington Post this week, saying that if the anti-trans “bullies” get their way, “they will drag down with them every compassionate, kind, loving women at the festival who gave me hope, joy and confidence.”

As this year’s festival winds down, the world is watching — what’s next for Michfest?

Change Is Gonna Come… From Within?

When we were contacted about running advertising for Michfest and attending, we eventually declined, explaining that it was impossible to reconcile this website’s goals of trans allyship with attending Michfest, or even accepting their ad dollars. We’d published a positive article about the festival from a guest writer, back when we were absolutely not allies in any capacity and us editors were obscenely ignorant about trans women’s issues in general, but we’re trying to eventually deserve the honor of “ally” now. (I’m ashamed and retroactively shocked that I, too, was once easily convinced that the womyn-born-womyn policy was sound and fair, and even defended it.) Due to various linguistic run-arounds from Lisa Vogel, there was a lot of confusion about the actual status of the intention amongst outsiders — the festival volunteer who first told me about Trans Women Belong Here, who fight for inclusion “from the inside,” told me trans women were now welcome at the Festival. The full-time staffer who’d reached out to me about attending denounced the womyn-born-womyn intention, but encouraged me to attend and said Festival was home to a diversity of perspectives, including a lot of activism happening on “the inside.” Michfest supporters often talk about “fighting from the inside,” insisting that dissent is welcome on The Land and so if you really truly care about trans inclusion, you’d buy a ticket, show up, and complain about it once you get there.

There might be some merit to this concept — Bevin Branlandingham of Queer Fat Femme, who has been attending the festival for 12 years, believes that initiatives like the four-day “Allies in Understanding” workshop she co-facilitates will eventually lead to a change in this intention. This year, she’s used her instagram to “document actions and conversations and workshop reports about the work going on in the ferns for Trans womyn’s inclusion at festival.” Others argue that a commitment to “dialogue” is overly generous, as it treats bigotry with too much compassion.

In an op-ed for Michigan-based alt-weekly Pride Source, transgender writer Zoe Steinfeld spoke out against alleged allies who attend, declaring that “to judge [a marginalized woman] an outsider based on a violent patriarchal system of sex assignment is not feminist. To echo conservative paranoia about her isn’t progressive. To attempt to speak in her stead — by wearing a t-shirt and attending a workshop — while paying to enjoy the institution that silences her, isn’t allyship.”

Whipping Girl author Julia Serano doesn’t think allies can “fight from the inside,” noting that “If you look back at history, there has not been a single instance where people have overcome a deeply entrenched prejudice without first being forced to interact with the people they detest. Mere words cannot dispel bigoted stereotypes and fears; only personal experience can.”

Tobi Hill-Meyer, a trans activist and writer who spent half a day at Michfest in 2008 and the full week in 2011, described a Michfest experience that echoed that assertion — “bias like this is able to flourish when trans women remain an unknown boogie monster… I talked with a woman who opposed trans women at the festival and after five minutes of sharing my story she told me that she didn’t know what the larger answer was but that she knew I belonged there.”

But Tobi also pointed out that when considering if allies should boycott the festival or not, it’s important to look at what those allies are doing when they attend. “I get the sense some people treat it like their vacation, enjoy camping, smile at the few trans women who attend, then maybe spend one afternoon attending a workshop conversation on the issue and will call that “working from the inside,’” she told me. “I know other allies who have created safe spaces, spent hours at a time on the side of the road flyering and engaging others, organized actions, taken direction from the trans women in attendance, who have pushed to make the segments of the festival they work with to be trans welcoming, who’ve been yelled at, demonized, targeted for harassment and more,” Tobi said, adding that she was “truly grateful” for “the allies who directly supported me while I was there — their support helps make it possible for trans women to confront these stereotypes and fears in person.”

But many others have come to believe that any ally’s best route towards genuine allyship is to stay home. Transgender writer Annie Danger said in a 2010 letter to her feminist friends who attend Michfest, “I am having a hard time separating your attendance of MWMF and your silence with me about this issue from your level of respect for me; for my body… What I hear is that the festival is a powerful and welcoming other planet where women’s lives, pains, struggles, and hopes are more commonly understood. This is allegedly a place of healing based on welcoming. A harsh toke for me: This is a place where I, on a body level even more than a political one, am profoundly unwelcome.”

Facing The Music, 2013 Edition

While I was going back and forth with the Michfest staffer in 2013, a situation that’s almost become an annual ritual starting just before spring and stretching into the summer was already underway — a series of scheduled Michfest performers were canceling, activists were calling for a boycott, and festival producer Lisa Vogel was gearing up to release an insufferably unsatisfactory “statement” regarding why the festival continues clinging to this outdated definition of “womyn-born-womyn.”

Jenn Burleton, a trans musician who played Michfest in the ’80s and ’90s while keeping her trans status a secret, is one of many who think performers who choose any route besides refusing to play are just caving in to the most radicalized and misinformed voices.” It’s in that spirit that in 2013, comedian/activist/writer Red Durkin called for a boycott of Michfest and its performers until the policy was changed.

Andrea Gibson dropped out in March. In April, The Indigo Girls announced that this would be their last year at the festival until the policy changes. The Indigo Girls are festival mainstays, and Amy Ray‘s partner is a longtime Michfest volunteer. By taking a stand, The Indigo Girls weren’t just standing up against political adversaries, they were severing decades-long friendships. I anticipated their withdrawal would be the ultimate catalyst for change, yet the festival’s intention lives on.

Nona Hendryx dropped out in June. JD Samson, who’d been attending the festival for half her life and was pulled from a number of queer events for playing it, announced in June that she remained confident “that the MWMF will one day become a place of safety, solidarity, and unconditional love for ALL Womyn,” but that “this will be my last year attending the festival until that day comes.”

Then Lisa Vogel released her 2013 statement of intolerance, which included the following:

The Festival, for a single precious week, is intended for womyn who at birth were deemed female, who were raised as girls, and who identify as womyn. I believe that womyn-born womyn (WBW) is a lived experience that constitutes its own distinct gender identity.

As we struggle around the question of inclusion of transwomyn at the festival, we use the word intention very deliberately. Michigan holds this particular lived experience of womanhood as honorable, meaningful, unique and rich. Our intention has always been coupled with the radical commitment to never question any womon’s gender. We ask the greater community to respect this intention, and to value the complexity and validity of every gender identity, including that of WBW. The onus is on each individual to choose whether or how to respect that intention.

See, Michfest’s present strategy is to eschew the word “policy” by using the word “intention,” and to insist they don’t refuse ticket sales or forcibly eject trans women, they just request trans women “respect” the intention by not coming. It seems really truly absurd for lesbian organizers to claim that an environment in which trans women are merely tolerated rather than embraced or welcomed could ever be a fun event, let alone a Utopia of Self-Acceptance. Sure, many trans women attend and have a good time, but even if nobody is questioning the trans status of attendees, how comfortable could a trans woman feel at an event where she’d been asked to not attend out of respect for women? How can we ask members of the most economically disadvantaged group in the LGBTQ umbrella to buy $400+ event passes and undoubtedly expensive plane tickets to Grand Rapids in order to attend an event also attended by womyn who find their very presence threatening to the safety of their space?

As Tobi told me, this lingustic run-around does enable Lisa Vogel to abdicate responsibility for the situation, despite the fact that trans women remain unwelcome. “In practical terms,” Tobi said, “[the intention] means that very little if anything is ever done on an institutional level to confront transphobia or anti-trans harassment.”

Shortly after Vogel’s 2013 announcement, the staff member who’d reached out to me resigned from her position at Michfest, citing her inability to reconcile this “intention” with her personal politics as the straw that broke the camel’s back. She was the only full-time employee who was outspoken about inclusion and the first (and possibly only) to quit over it.

The losses kept piling up, but Michfest persisted with the intention.

Play It Again, 2014 Style

This year, Lea DeLaria‘s participation had barely even been announced before it was redacted. Hunter Valentine had already declared in March that they were withdrawing, noting that “we have always felt and identified as positive trans allies and feel that playing the festival would directly contradict our beliefs that a trans woman is a woman and should be seen, respected and treated as such.” Xoe Wise and Baskery also dropped out once they were made aware of the policy. More recently, Antigone Rising published an Op-Ed in The Advocate about why they’d never play the Festival again.

Those who have remained on the ticket have often lost gigs elsewhere — Bitch’s participation in Michfest has led to her losing gigs as far back as 2007, when she was uninvited to the Boston Dyke March. The truly fantastic duo Climbing PoeTree were pulled from Oregon Queer Students of Color Conference this year ten days before the conference began. OQCC stated that although they don’t consider the girls transphobic, they disagree “regarding our approaches to solidarity and activism surrounding Michfest.” Climbing PoeTree wrote on their blog that they oppose the intention, but planned on playing regardless and donating their proceeds towards “supporting a convening, event, coalition or institution that reflects the values of inclusion we want to embody moving forward into the future we are collaborating to create.”

Subsequently, festival producer Lisa Vogel sent an e-mail to former Fest attendees begging them to support the festival if they want it to continue past this upcoming year. She explained how they could buy honorary tickets and make donations, but also implored supporters to rally around the musical artists who, by playing Michfest, have now been “harassed on their Facebook and twitter pages, creating political controversy for the artists, subjecting them to public shaming and resulting in very real economic loss, losses that none of these independent artists can possibly shoulder alone.”

In that e-mail and many other communications, Vogel was engaging in the same rhetoric and logical fallacies that have been employed by trans misogynist feminists since the dawn of time, wherein they can play the victim by re-framing deserved backlash as unprompted aggression. She’s also ignoring the fact that trans womyn who attend also face harassment. Tobi found herself on a “hit list” after attending The Festival and subsequently “targeted for online harassment” including people “ridiculing my appearance, tracking down my parents’ contact info and sending them hate mail and links to naked pictures of me.” The next year, Tobi was “emailed threats warning me not to attend again.” Although “a large portion of the women I met at the festival welcomed me,” ultimately, Tobi found Michfest “both one of the most affirming, welcoming and supportive places I’ve ever been and simultaneously the source of incredible hostility and the worst harassment I’ve ever received.”

“We’re not demanding they let us in, but that they stop pushing us out,” Zoe Steinfeld wrote. “We’re not invading women’s spaces with men’s bodies, we’re women banished from our own spaces.”

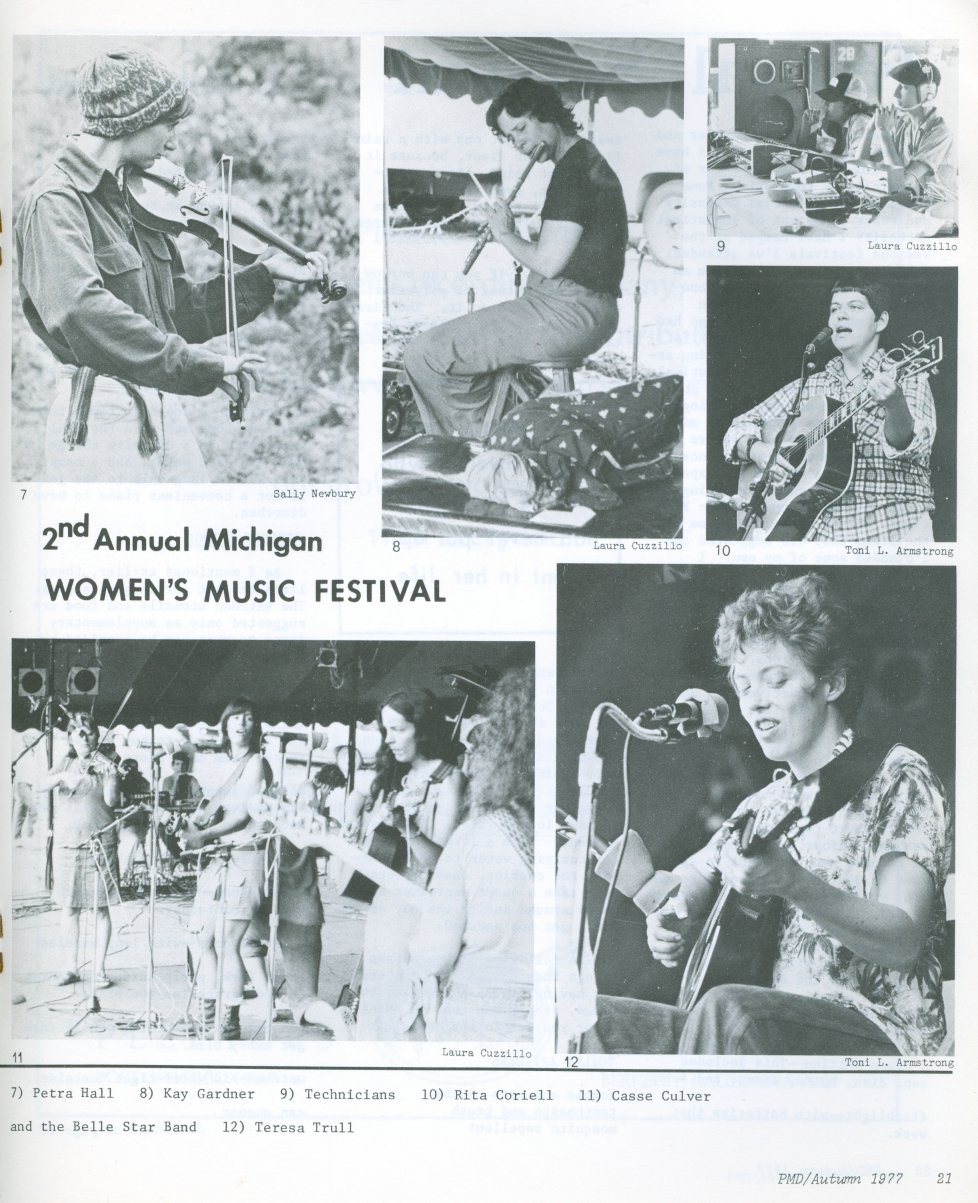

The Mothers Who’ve Paved The Way: Michfest’s Legacy

When I talk to my peers about Michfest, which attracted up to 9,000 campers at its peak and now brings in more like 3,000, most of them don’t know anything about it besides that it’s not open to all women. They don’t know the history or how the festival sprung out of a movement centered around women’s music and the idea of self-sustaining economies. As Lindsay Van Gelder and Pamela Robin Brandt write in the 1997 book The Girls Next Door, the women’s music scene provided “our first real alternative to gay bars.” Artists who have played Michfest over the years include Cris Williamson, Holly Near, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Pamela Means, Nedra Johnson, Tracy Chapman, Ani DiFranco, Le Tigre, The Butchies, Gina Breedlove, Northern State, Tegan and Sara, Sia, BETTY, Chris Pureka, Melissa Ferrick, THEESatisfaction, Team Dresch, Mary Gauthier, Laura Nyro, Staceyann Chin, Jill Sobule, Toshi Reagon, Kinnie Starr, Dar Williams, Pat Parker and Erin McKeown.

Lisa Vogel was a 19-year-old working class college dropout from Michigan when she came up with the idea for Michfest — while stoned and on a road trip — and the first proto-Michfest event was held in 1975. “The festivals pioneered much of what’s progressive in lesbian culture: sliding-scale ticket prices, free child care, signing for the hearing-impaired,” wrote Brandt & Van Gelder. The food is vegetarian, the workshops are heavy on drum circles, meditation and sexual exploration, and all work on The Land is done by festival volunteers and attendees. There’s also a sliding scale to make the festival as accessible as possible. This year’s workshops include “Breast Casting for Womyn of Color,” “Healing Ways for Rising Amazons” and “Challenging Internalized Misogyny.” All work on the land, from the building of the stages and other facilities to the preparation of communal meals, is conducted by women. Michfest’s accommodations for disabled women and commitment to the inclusion and celebration of women who are queer, of color, working class, of size or gender non-conforming set a new standard for women’s events.

But rifts regarding the inclusion of trans women have been present in the women’s music scene from the beginning, which might account for why trans women are so underrepresented in women’s music. Preeminent women’s music label Olivia Records was forced to confront its definition of “womanhood” decades before Michfest did, in fact. Starting in 1976, Olivia was swamped with hate mail for employing a trans female lesbian recording engineer who was later attacked directly in Janice Raymond‘s 1979 transmisogynist hate screed, The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male. The transgender engineer was forced to leave Olivia, an early example of what would be decades of tension between lesbian feminists and trans women in music.

Michfest’s own controversy began in 1991, when a trans woman named Nancy Burkholder drove 1,050 miles from New Hampshire to Hart, Michigan, with her girlfriend Laura, to attend the festival for the second time. By nightfall on the first day of Festival, Nancy had been outed as transgender and subsequently dismissed from the festival. Her account of this horrifying situation was posted on Transadvocate last year:

We walked and talked with women waiting with us on the road, bought raffle tickets from a festival promoter, and joined women in joyous enthusiasm, camaraderie and expectation while we awaited the start of the festival…

…I was approached by two women, Chris Coyote and Del Kelleher. Chris said that she needed to speak with me regarding a serious and difficult matter. Sensing her urgency I suggested we move away from the women near the fire pit in order to talk privately. Chris said that the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival was a woman-only event and she wanted to know if I was a man. I replied that I was a woman and I showed her my NH picture ID driver’s license. Then she asked me if I was a transsexual. I asked her what was the point of her questioning and she replied that transsexuals were not permitted to attend the festival…

… She told me that I had I had to leave the festival and that I would not even be allowed to return to my campsite to retrieve my equipment. I realized that Chris and Del were expelling me in spite of all the irrefutable legal and anatomical proof that I was a woman. I knew there was nothing more I could say to these women. I resigned myself to the fact that these women were expelling me from the festival… From the time Del and Chris first approached me until I left the land, I was guarded and forbidden from leaving the area around the fire pit…

…. At about 12:50a.m. Laura returned with all of my equipment and her car. We departed the land. In less than two hours and under the cover of darkness, the festival personnel had expelled me from the land.

Protests against this policy began in 1992. That same year, a survey of Michfest attendees (with a response rate of 8.4%, or 633 of 7500 attendees) found 73.1% were in favor of transgender female inclusion. The “Camp Trans” counter-event protest began in 1994, when 30 activists held workshops near the Michfest site for three days. Camp Trans continued on and off for many years to mixed results. In 1998, the Washington DC wing of activist group Lesbian Avengers wrote Michfest organizers to state they would not continue attending the festival because “your womyn-born-womyn only policy is unnecessary, arbitrary, and harmful to our community.” Other Lesbian Avengers factions would participate in Camp Trans in ensuing years. Around that time, Michfest organizers claimed that activists from Son of Camp Trans had infiltrated the festival, flashed their penises in public showers and disrupted a teenage girl’s discussion group when in fact, it was a transgender man who’d had phalloplasty who was spotted in the showers. Camp Trans lulled for a bit before being re-ignited in 1999, as explained by Michelle Tea in her 2003 Believer essay, “Dispatches from Camp Trans,” but had become dominated by trans men. Camp Trans organizer Bryn Kelly explained, “I love Camp Trans and I love many of the people I have met there over the years, but if you compare the two, let’s face it, Camp Trans was always kind of a shit show. CT had probably about 2% of the budget of Michfest, so going to the Festival after having camped at CT for so many years kind of felt like being at Disneyland.”

Although momentum against the intention has been building at an increasingly rapid pace over the past few years, it bears mentioning that the “we support the inclusion of transgender folks but still plan to play the festival” line, expressed this year by Crystal Bowersox, has been brought out for 15 years to no real end. “Take a look at newsletters in the Lesbian Herstory Archives and you will see that we’ve been having the exact same arguments about this issue for the last thirty years,” Bryn Kelly told me.

In 2006, supporters of trans inclusion declared that the “womyn-born-womyn” intention was no longer in practice after a Camp Trans organizer was sold a ticket, but their press release was met with a swift rebuttal from Lisa Vogel reiterating that “Despite claims to the contrary by Camp Trans organizers, the Festival remains a rare and precious space intended for womyn-born womyn.”

Trans women who have attended Michfest feel a profound dissonance on the land. “I cut myself off after one beer, because I was afraid if I did anything even accidentally stupid, it would not just reflect badly on me, but on ALL TRANS WOMEN FOREVER,” Bryn said. “Supposedly, this festival is about being able to let your guard down; I had mine up the whole time.”

“There was definitely some intense hostility, but for every scowl directed my way, there were ten smiles,” Tobi remembered. “For everyone who told me I shouldn’t be there, there were five people inviting me to parties or to work with them. For every person who harassed me, there were three who held me in their arms and consoled me about that harassment… but at a certain point, the presence of negativity can’t be cancelled out just by having other people be positive.”

Considering the overwhelming support for inclusion from festival performers and the apparent solidarity of a majority of ‘fest attendees, it remains profoundly confusing why the policy persists. In our annual Autostraddle reader survey, for which 94% of respondents were between the ages of 18 and 44, only .4% (13 people) of over 4,000 said they’d been to Michfest, and only 5% said they planned to or wanted to attend. So, in total, only 5.4% of our readers wanted to or had attended Michfest — and 46% had never even heard of it. Other events pulled in radically higher numbers of respondents who had or wanted to attend, even events that weren’t explicitly queer: 52% for A-Camp, 39% for Comic Con, 35% for South by Southwest and 22.4% for Dinah Shore Weekend. Even Olivia Cruises — the only remaining wing of the Olivia Records empire — pulled in an 11.3%. Although Michfest ranks above Aqua Girl, Girls in Wonderland, GaymerX and R Family Vacations in terms of popularity and reputation, it’s also less well-known or desired than Lesbians Who Tech, a conference that just started this year but was extensively covered by and advertised on Autostraddle.

Michfest isn’t incapable of evolution — early festivals were criticized for designing the event from a white middle-class perspective, lacking women of color performers, and appropriating indigenous spiritualities, symbols and practices. Now it’s one of the most racially diverse women’s events in the country. The addition in 1986 of a womyn-of-color only sanctuary also helped encourage solidarity and change. The 2014 lineup poster features 32 acts — 64% of those acts are women of color. That kind of diversity is amazing and unprecedented and undoubtedly would be inspirational to the many trans women of color who are unwelcome at festival, despite being the most oppressed group within the LGBTQ umbrella. Why can’t Michfest evolve on transgender issues, too?

Which Side Are You On

The justification for this policy is approximately this: that cisgender women experience a “shared experience of girlhood” honored by the womyn-born-womyn policy and violated by transgender women, who organizers argue grew up with male privilege and would contaminate a “healing space.” There’s also often talk of the sexual violence inflicted upon women who may be triggered by the sight of penises on the land (despite the fact that realistic dildos are sold in open public spaces). Often that trusty ol’ straw man of “men will sneak in by pretending to be women and then assault us” is trotted out as well.

First of all, transgender women are more likely to be victims of sexual violence than any other group. Secondly, the concept of a “shared girlhood” universal amongst all women fails on a few fronts, like that it ignores the ways in which different intersectional identities mean that experiences of girlhood vary extraordinarily widely, and vastly overestimates the impact of male privilege on the life of a transgender girl.

It ignores that “not all women are equally privileged or oppressed,” writes transgender “social justice activist/writer/rogue intellectual ” Emi Koyama in her 2006 essay Whose Feminism Is It Anyway?. She writes that “…in the women’s communities, trans(gender) existence is particularly threatening to white middle-class lesbian-feminists because it exposes not only the unreliableness of the body as a source of their identities and politics, but also the fallacy of women’s universal experiences and oppressions. These valid criticisms against feminist identity politics have been made by women of color and working class women all along, and white middle-class women have traditionally dismissed them by arguing that they are patriarchal attempts to trivialize women’s oppression and bring down feminism.”

Personally, I’ve found that class, race, ability status and gender presentation bear enormously on the nature of every individual woman’s girlhood and that one’s relative privilege is a far greater predictor of a degree of commonality than gender assigned at birth alone.

Besides, “considering how much “male energy” is used as an excuse to target trans women,” Tobi said, “one thing that really surprised me was just how much male energy there was. Within the first 30 minutes of arriving at the main stage, one musician sang a song about her cock and another one was introduced with male pronouns… by the end of the day I’d met a half dozen trans men, most of whom had been attending for years and were well known.”

The Woods Are Disappearing

“What I fear more, what I fear most, more than man, the beast, or the ghost, is that the woods are disappearing.”

– Dar Williams, “Go to The Woods”

There are women who have always attended the festival and always will. Much like repeat attendees of A-Camp, the annual camp/conference/festival hybrid primarily aimed at queer women that Autostraddle hosts in the San Bernardino mountains every year, these dedicated festies consider Festival “home” and a sacred time to convene with friends/”chosen family” in a familiar space. But in order to survive, Michfest will need to attract a new generation of women, and that’s not gonna happen if they don’t change the policy. Acts that would appeal to a younger audience — like Andrea Gibson, MEN and Hunter Valentine — won’t play the festival ’til the policy changes. Meanwhile, there are other options for the people MichFest aims to attract — like A-Camp, which has always been open to trans women attendees. For many campers (and staff members!), A-Camp is the only place where they even have the opportunity to meet and befriend trans women, a crucial exchange for political progress and productive allyship, which’s one of many reasons why we prioritize trans women when distributing camperships (we do the same for women of color).

It saddens me every time a trans woman emails us before signing up for A-Camp to make sure she’s “allowed” to attend. It shouldn’t surprise me, but it does. Michfest reflects poorly on lesbian feminism in general and, unfortunately, as Tobi pointed out to me, Michfest’s intention “has wide-reaching repercussions as feminist organizations around the world look to it as a model and have used it as a justification to keep trans women out of rape crisis clinics, domestic violence shelters, and other vital resources.”

I realize that Lisa Vogel probably feels like young peoples’ perspective on this issue is hopelessly ahistorical because a lot of modern queer politics are hopelessly ahistorical, much to the chagrin of those looking to build community between generations. I know how easy it can be to cling to traditional politics, partially because opposition to them is being preached by people quick to discount and disrespect decades of genuinely productive and progressive, if flawed, activism, over a very recent failure to “keep up.” But this isn’t a new issue. This has been going on for decades, and led by activists from multiple generations; it’s only now that the fight against the “intention” has gone gaystream.

This year’s lineup includes really talented and incredible acts that undoubtedly are limited, by their politics, race, sexual orientation, gender presentation or some combination therein, to the types of gigs they’re solicited for and therefore their ability to survive economically. Michfest makes these women choose between financial survival and allyship. Michfest makes volunteers and festival attendees choose between the only place they’ve felt accepted as a fat/disabled/butch/of-color/queer woman and allyship. Michfest creates personal riffs, too — I can’t imagine how awful it must be, as a trans woman, to see your cis friends and/or partner(s) attend an event you can’t attend. This needs to stop. We have to be better than this.

Next year marks the 40th Anniversary of Michfest, and I can’t think of a better opportunity to change the intention. It will be a fuller and more productive festival with a more robust lineup of performers and an environment that encourages compassion over division. “Denouncing Michfest as outdated, irrelevant or out-of-touch will only dig our enemies in deeper and drive potential allies away,” wrote Kayley Whalen. “Even worst, if we do we lose the opportunity to bridge the gap between generations of feminists, and divorce ourselves from our own history. An inclusive festival can inject new life into our collective fight against sexism, racism, classism, homophobia and transphobia.”