The first memory I have about feeling strong and confident involved moving something heavy. It was around the time that I went from being the tallest kid in my class to the biggest. I was constantly slamming my newly widened hips and shoulders into furniture and door frames and could not figure out what my stocky frame was good for.

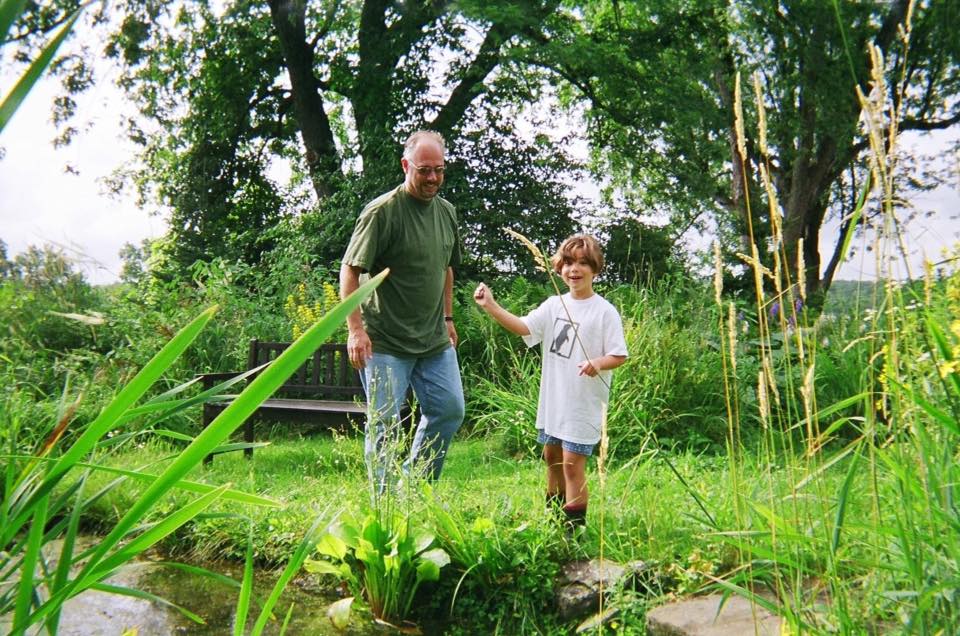

Every year my family drove up to Michigan to go camping for a week free from the eyes of my peers and the corners of furniture. My dad loved the outdoors and thrived during this week. He would stay up late with a campfire and show me constellations, teach me the different kinds of trees, quickly grab me to point out birds before they fluttered away, and share his joy for simply existing in the outdoors.

So when I filled up an empty water jug and carried it back to the campsite, and my dad said, “Wow, I don’t think I could have carried anything that heavy at your age,” I was stunned.

I felt like I had earned my place, and he treated me like it too. Every camping trip from then, on it was me and my dad against the world. We carried the water jugs to the campsite for dinner. We set up the tent to protect us from the elements. We would problem solve the getting three bikes into our small car together. My dad treated me like a peer, and I felt strong and confident. As strong as my dad, and much stronger than my mom. She would set up a camp chair by the fire and read. Sometimes wash the dishes, although only if we were staying somewhere that had a sink. She had no interest in lifting the heavy things and I could not understand why.

I started going to summer camps and spending a few weeks living in cabins with other preteen girls doing various outdoors activities like archery and day hikes. But I wanted to go backpacking, just like my dad. One summer he went on a trip in Arizona with my uncle who’s a wildland firefighter, so my dad was nervous about keeping up with him. We went on walks around the neighborhood, me with our dog and my dad with his full backpack.

After seeing the pictures and hearing the stories from that trip, I knew I needed to do more camping. I didn’t want to sleep in cabins, I wanted to sleep in tents. I didn’t want to be gone for a week, I wanted to be gone for a month. I wanted to come back with pictures and stories to impress my dad. Maybe then he would see I was strong enough to go with him and my uncle, even though I knew I wasn’t. Yet.

My mom found a summer camp that took teens on backcountry trips. The trips started with 5 days and got longer and more remote each year; the last trip was 45 days long in the Arctic. But it was expensive. I didn’t think we would be able to swing it. But I remember sitting with my parents in the living room, watching the promotional video and my dad saying, “Yeah, this is the ticket. We’ll figure out how to get you in.”

In the spring, when it was time to start figuring out how to apply for scholarships, my dad died. He went into the hospital with a bad cough and a high fever, and died on the day they had said he was supposed to leave. I was 15. My mom fell apart.

He died the first Saturday of spring break, so I didn’t miss school. Not because I wanted to be there, but because I didn’t want to be around my mom. She was weak, and so I had to be strong. I was lifting the heavy things for both of us because I had to, but I hated her for it. I honestly still do.

![]()

I went to that camp for two weeks in August, five months after my dad died. I’m sure I was the weirdest kid my counselors ever had, but it was an incredible two weeks for me. I portaged a canoe! Have you seen someone do that? You lift the canoe, flip it up and over your head, and then you walk. With it resting on your shoulders. Finally, something my wide shoulders were good at.

I could carry that heavy canoe further than any of the other teenage girls on my trip. Not quite as far as my counselor could, but still far enough for her to confide in me that I she was worried about the 2 mile portage we had the next day and ask me if I was feeling good about carrying one of our three boats the whole way. Of course I was. I could carry her worries and that canoe, because that meant I didn’t have to carry my grief and my mom had to carry her own weight, because I wasn’t home.

When I got back, there was no food in the fridge and dishes that hadn’t been washed since I left. So I carried her for the fall, winter, and spring, and lived to be able to carry canoes in the summer. I went back every summer all the way up to that 45-day trip. I spent a glorious seven weeks in the Arctic with seven other people who know the joy of lifting heavy things. We traveled North together against the wind, pushing ourselves every foot of the way.

When I came back from that trip, carrying my dad around didn’t always feel so heavy. He would have taken me backpacking with him after that; I had been on a longer backcountry trip than he ever had. Now he would be the jealous one of my amazing pictures and stories. But instead the only person I had to show them to was my mom, who would never understand the joy of carrying something heavy for so long.

Until I met this woman. This beautiful, kind, intelligent woman. We held hands while we walked across our college campus, and I got butterflies in my stomach and throat. I showed her pictures from that trip in my dorm room and I kissed her. I hadn’t really put much thought into how I identified before that; it was one of those heavy things I didn’t want to mess with. But her touch made it light. Being queer wasn’t a burden, because she made it filled with joy. She holds me and allows me to feel because I know now I’m not carrying anything alone.

I spent falls, winters, and springs with her and the summers at camp, teaching preteen girls how to portage. I would lift the canoe, flip it over my head, and walk with it. They would watch in disbelief, knowing without a doubt that this was something their newly grown bodies could not do. But they did. I would help them lift that canoe, flip it over their heads, balance it for them while they walked with it. I helped these young people do something they thought was impossible, and I’ve never felt more alive.

Camp was one of the first places I had the freedom to explore what it being queer is to me. For me that first summer, that looked like wearing and oversized green button up jacket I got at a thrift store, putting one rainbow sticker on my water bottle, and then taking it off after a week, and reading a lot of Andrea Gibson, but not talking to anyone about it. I would try to confidently and boldly step forward, but out of fear of rejection and my own shame, I would step back.

![]()

Three years from that tentative first summer, I told myself that fear of rejection was not real – at least not at Camp. I had been hired back multiple years in a row after being publicly out, which is thanks to work that people my counselor’s ages had done, so I was ready to do some work to make this a better place for my campers and friends. We started running a queer inclusivity training – a place for people to get the chance to ask questions, learn the definitions of the queer alphabet, and brainstorm things we could do to improve the cultural environment for our campers and friends.

So in my last summer at Camp, when one young staff member brought up the idea of having safe space sticker with a canoe on it, I ran with it. It went surprisingly poorly at first. People on the administration team found out and told me I wasn’t allowed to distribute them. They confirmed all the fears I had about being rejected for my queerness.

But they couldn’t take away all the work I had done. It could have made me feel like I shouldn’t be allowed to lead teenage girls. It almost made me feel I shouldn’t have been allowed to share a tent with them and sing them to sleep, to bring them new clothes during a thunderstorm, to hold them while they cried, to celebrate and rejoice with them for finding out what their bodies and hearts could do when they pushed themselves to their limits.

But it didn’t, and that wasn’t because of my own work; this was a heavy thing I could not lift alone. My straight friends didn’t let me — when I was burnt out and had given up, they kept working and talking and pushing until eventually they got permission to pass the stickers out. Within the week there were rainbow stickers everywhere.

People started coming back from trips and telling me stories. Our first trans camper came back and identified so strongly with their experience and the organization that they asked for five stickers. One girl stared at her counselor’s sticker covered water bottle for ten minutes before starting to ask for advice on a situation with her girlfriend. My queer friends all across the country have stickers on their water bottles, cars, and framed on their walls.

That experience changed the way I think of myself as an outdoor educator and taught me that inclusion and safety are not automatic. I was raised by a someone who told me I was strong, smart, capable of challenging myself, and that I belonged in the outdoors. Now I am working to be that person for others, so that they can come outside and accomplish something they thought was impossible.

A few years ago, I got a tattoo of a Jack Pine. On those family vacations my dad used to collect their pine cones in his pocket all day and then set them near the fire at night to show me how they open in the heat. They are a tree that has evolved to be dependent on fire. That heat is the only thing that will make their pine cones open and release the seeds inside. What looks like a dead and destroyed forest, is actually full of light and carbon for their saplings to grow and thrive. I aspire to be like them, and in heavy situations, find the source of strength and light to lift up myself and the people around me. 🌲

edited by rachel.

wow this series keeps on giving.

thank you for this Tess. <3

What an inspiring story. Thank you so much for sharing it.

This took my breath, just a bit.

I love this focus on strength! Last night my eight year old said she wants to eat healthy foods so she can “grow up to be a strong woman” and it made me smile. Instead of cautioning her to be safe, I’ve shifted to encouraging her to have adventures! Thanks Tess for sharing your stories about strength and adventures!

Also I have been appreciating the stories on Autostraddle about dealing with the loss of a parent as a kid, as my shared kids lost both of their bio parents several years ago.

GORGEOUS

Wow I am weeping! What beautiful writing. Thank you for sharing <3

This is so beautiful. Thank you for sharing.

Those kids are lucky to have someone like you to help them learn to be strong.

Thanks, Tess. I’m sure your leadership is making a difference for a lot of kids.

Hoping to take my daughter kayaking for Mother’s Day. I miss going kayaking with my dad.

Oh, this hit me hard. Thanks, Tess!

what a beautiful piece ❤️ so glad canoe tripping got some time in this issue, makes me think of all the paddling and portaging that shaped me growing up.

Wow. Thank you Tess!

😀☹️🥺😋

10/10 would go on a canoe trip involving portaging with you

Oh my god, that’s wonderful. Thank you so much.

Whewwwww. Gorgeous writing, and relatable – this is inspiring as I think about my upcoming summer job in the outdoors.

“I could carry her worries and that canoe, because that meant I didn’t have to carry my grief and my mom had to carry her own weight, because I wasn’t home.”

Wow thank for sharing this!

This is beautiful. Thank you for sharing it <3

This. My heart.

Carrying a canoe for two weeks at age 13 was a truly life-changing experience. I was stronger than I ever imagined. I went back every summer for 5 years, with my last trip a truly grueling and glorious 30 days crossing the Hudson Bay. Beautiful essay. Thank you for sharing!

♥🛶💪

“The joy of lifting heavy things”

Oh my goodness. This piece is stunning, thank you.

I loved this. As a kid who didn’t always fit in, paddling for hours and humping canoes across portages gave me confidence. It also taught teamwork far better than any team sport.