It’s Not Me, It’s Them: On Wanting To Break Up With Facebook

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” column exists for individual queer people to tell their own personal stories and share compelling experiences. These personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.

Thursday was a normal day – I worked 8 to 12 and 2 to 6, wrote an Autostraddle article on my break, thought about my dog, and waited for a bus for 25 minutes to get home. That was when it happened.

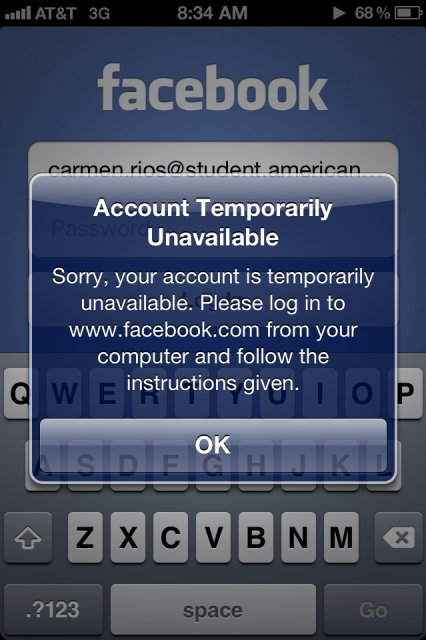

I attempted to log in to my Facebook at approximately 6:10 PM. I hate the Facebook app for the iPhone, so when an error message popped up I moved back on to my Drake mix. The bus came. I went home.

That was when it happened.

Facebook dot com slash checkpoint. My personal content, presumably images, from Slutwalk DC reported as being from 2012 despite being posted in 2011 had been deemed offensive or otherwise unfit from a member of the Facebook team. Now I wasn’t being let in, despite having been a member of Facebook since 2007 and sticking with the network after the rape joke controversy, after they complicated the layout in an effort to cover up Mark Zuckerberg’s robbery of intellectual property.

Despite the knowledge in the back of my mind that I use Facebook for work, for activism, for projects, I hesitate even now to ever proceed past the checkpoint. Because I’m sort of a slut. Because I can’t promise to ever surrender to anyone, and especially to an oppressive website. Because I know it will and can happen again. Because Facebook broke up with me and instead of muttering “it isn’t you, it’s me” half-heartedly while texting their next girl, they told me I had to change to find a place in their world. And yet, the idea of completely letting go is conflicting and difficult.

Facebook is a website we are sort of programmed to use, kind of trapped inside of. When my friends deleted their Facebook profiles throughout college or high school, the question was never “why” because we all know why: because it is run by sexists, because it capitalizes on human socialization for greed, because it makes us into socially awkward and socially anxious little humans and because at the end of the day, your ex is still posting lame poems on her wall and it will inevitably show up in your feed. The question was always how: “how will you know when people are partying?!” and “how will you remember your entire life via images posted on this website if you don’t have one?” How will you stay in touch with me from Paris? How will you wish me happy birthday from New Jersey? Without Facebook, do you exist? The verdict was always out.

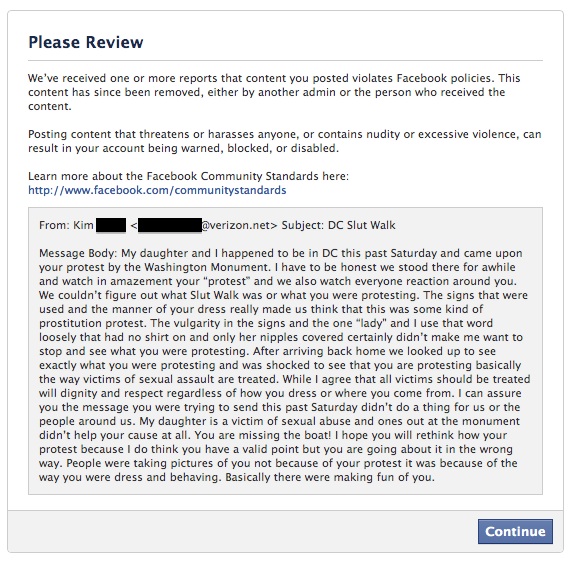

The ability to report content as offensive, harassment, spam, or otherwise in violation of Facebook’s community standards is a valuable tool. The problem is that the tool requires a subjective opinion behind-the-scenes, and that Facebook has proven again and again that those opinions are not progressive or based in a desire for equity and safety for its users. Despite Facebook including a note that “it’s possible that something could be disagreeable or disturbing to you without meeting the criteria for being removed or blocked,” my Slutwalk content was removed. I was locked out of my own account unless I agreed that posting pictures of the activist movement that I was honored to be a part of was offensive, and essentially recanted.

Facebook dragged their feet at the mere idea of removing pages and groups that poked fun at rape and sexual violence, and even incited the act, despite safety being described in their community standards document as their “top priority.” As a queer woman of color, I have been asked to quiet down many times. At bars, on the subway, in my dormitory lounge, in classes, during meetings, in my Camp cabin, at my grandmother’s dinner table. When I began using the Internet I was amazed how easy it was to speak out, to be heard, to feel visible and present, to participate. Facebook is the main tool we used to plan the 2011 Slutwalk march, and it allowed us to remain consistently in contact with our volunteers. It is how I promote events ranging from my 22nd birthday bonanza to Eileen Myles’ speaking engagement on my campus in March. I have used Facebook to share my schedule with my friends each semester, post pictures from the Prop 8 protests in 2008, and post articles about how much I wished the company would put a woman on their board. Hate Facebook as I might, I used it because it is by far the most widely used network of its kind on the entire web, and the more connected it became the more relied upon I allowed it to be in my work, my personal life, and my bouts of boredom.

But now I face an attack from the platform that allowed us to share photos of my dog after he passed in 2008 as a family, a platform that allowed me to share ideas and get feedback, a platform I have used to spread awareness and build solidarity, a platform that made it possible for me to connect to people I had met and had loved but lived nowhere near and might not ever see again.

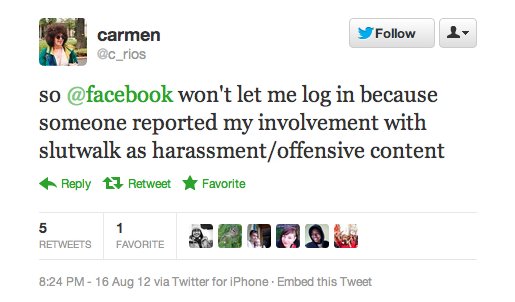

I posted about Facebook’s decision to lock me out of my account the night it happened, frantically attempting to summarize the situation in 140 characters.

The next day, I posted an image of the exact message I received at my checkpoint to Tumblr, and added some editorial about why I was troubled at the format of the warning. I was offered one choice: “continue.” In order to proceed to my home page, to my thousands of friends, to my five years’ worth of albums and my photos of Eli’s first bath, I had to hit “continue.” I had to admit I had done something wrong, had to retroactively give consent for the removal of my content, had to agree implicitly never to do it again. I didn’t even know what I had done, because Facebook hadn’t told me specifically which content was so offensive. In order to “continue,” what do I have to do? Maybe I have to stop going to controversial protests, or stop being someone who protests at all. Maybe I have to retreat back into a place of attempted “normalcy,” in which I comply with Facebook’s desire to silence my opinions but use my matter for marketing numbers. Maybe I have to stop being a slut, or stop believing in them.

If I hit “continue” I am almost lying about why I was on Facebook in the first place. I am pretending that I was on Facebook to conform, and not to amplify my own screaming. I am pretending that I ever gave a fuck about people like Kim who don’t agree with my revolution, and not that I enjoyed using the privacy controls to block adults and my conservative cousins from ever weighing in on what I believed in. I am pretending that I ever wanted to participate in an online community where I could be policed for believing in a world without sexual violence, silenced when I attempt to break the sound barrier. If I hit “continue” I accept without kicking or screaming that Facebook is not for me anymore, not the me I love, and I must kick and scream. Because I recognize that something wrong has happened. Because my Facebook did more good than my Tumblr post – because I used it to share petitions, to write feminist manifestos for my class, to spotlight misogyny. Because I meet regularly with activists on Facebook for my current projects. Because I was using Facebook both to connect to people and in an earnest and heartfelt attempt to do some good in this fucked-up world.

I feel now that I have been locked out of a gated community where all of my friends live and love, pushed out of a clique I started in the first place. In 2007 I begged all of my friends to move from MySpace to Facebook. Now I feel like there are no open apartments and I have nowhere to put my stuff.

I want Facebook to restore my content. I want Facebook to restore my content and send me an apology written in comic sans and get rid of that god-awful message and give my friends and family back to me and let me talk once more about what I believe in, what I ate for dinner, and who Drake beat up in the club. I want Facebook to give me back my virtual workplace and classroom of five years. I want Facebook to put a woman in their boardroom. I want Facebook to stand up and use the human power they have harnessed for something other than muting my already raspy and tiny voice.

I want Facebook to give me the freedom merely to exist.

And yet I feel in this instance that I am asking for too much.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.