Idol Worship: Frida Kahlo, Brutal and Vulnerable

Header by Rory Midhani

Welcome to Idol Worship, a biweekly devotional to whoever the fuck I’m into. This is a no-holds-barred lovefest for my favorite celebrities, rebels and biker chicks; women qualify for this column simply by changing my life and/or moving me deeply. This week I’m giving thanks to Frida Kahlo, the woman who taught me how to be ugly and be okay anyway.

I first learned about Frida Kahlo when I was in middle school. Sort of short and, well, big, I was textbook awkward dork: bad clothes, misguided social naivete, horrible applied practice of knowledge of heterosexuality. I was already depressed, forming what would become full-blown angst and sort of storing it up in my heart space for later.

I thought, at that time, that Frida Kahlo was interesting because she was this person, full-grown and tall, who thought she was ugly and still persisted in creating. It made her both brave and sad; poignant and persistent. She made art to survive, made art to prove she still existed, made art to establish she was still alive. Frida Kahlo was the first artist we ever learned about who I recalled as aggressively female, as an otherworldly femme, as someone unafraid to embody artistically what women are so often seen as being: emotional, complex, confused, overwhelmed by the sheer largeness of the world and what they still haven’t done.

I decided immediately upon learning about her that I wanted to be an artist, and made a set of three surrealist paintings, none of which were any good.

Frida Kahlo (born in fact with my name, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon) in 1907, is a Cancer – making her one of the only people I adore who doesn’t somehow get to call themselves a Leo. She grew up in what was a small town outside of Mexico City, raised by her mother and father, a German man who had changed his name and moved to the area after sailing there at 19. Frida was close to her father growing up, and he may be the one who filled her with strength and spirit; she had two sisters as well. She would grow up to not only be a notable artist, but also marry one, falling in love with Diego Rivera and marrying him in 1929. Their relationship began as a professional artistic bond, a sort of mentorship gone intimate. Her mother didn’t approve.

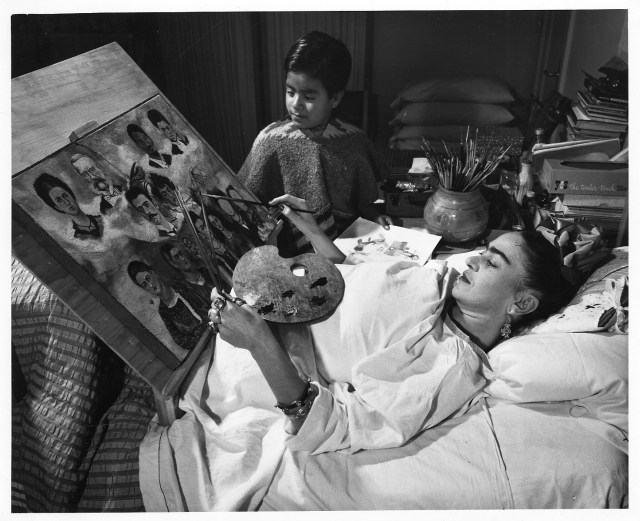

Kahlo contracted polio at six, rendering her legs different sizes than one another. At 18, she was riding a bus that collided with a trolley car, leaving her with serious injuries in her spinal column, collarbone, pelvis, leg, foot, shoulder, stomach and uterus. She spent three months in a full body cast and would never fully heal, forced to grit her teeth through over thirty surgeries in her lifetime as a result of the unfortunate accident. Frida Kahlo was bedridden, and her life would be fraught with challenges brought on by physical problems and ailments. She would never have a family: the accident had made it unsafe and impossible for her to carry a child, despite being pregnant three times during her life. Instead of family, she got miscarriages – instead of having happiness, she struggled with her own pain. While she healed, she made art.

Kahlo’s work many times took the form of self-portraits and often made tangible the pain which plagued Kahlo, emotionally and physically, for her entire life. She had a lot to work with; she drew and painted herself often as realistically as possible, which in middle school people didn’t understand because she was sort of ugly. It seemed very brave and stark to us, caught at the time in the middle of one of the worst social minefields of our lives, to see a woman sort of plastering her ugly face on things in order to express herself. I saw it as almost a form of brutality, as a vulnerability that healed, but preserved and sustained, pain.

“I never painted dreams,” Kahlo said. “I painted my own reality.”

What drew me to Frida Kahlo when I was in middle school is what has kept me immersed in art, in creative work, in dream-chasing for so long: creation as survival. Retelling as surviving. Art, even when I was 10 or 11, signified to me some form of escape, of rising above, of making it out alive. Artists needed pain – they needed it in order to live through it, and once they did that, they were made. I always assumed that was what was happening to me: I was ugly and I was teased and things were hard because they had to be, because I had to survive to get gritty, because one day I was going to shout or paint or sculpt it all back into life and then conquer it once and for all. Frida Kahlo was using art to redeem herself, to make peace with the life she had been given. But even more importantly, she made art to prove she was still there, to invest her time in her own healing, to take care of and love herself. Frida Kahlo made art to make peace with her life, and to make sure we knew she planned to survive.

Frida Kahlo wasn’t the first dark and tormented artist in history, nor will she be the last. But she is a standout. No matter what anyone says, she was remarkable.

frida kahlo and i both love boats

When I was a young girl staring doe-eyed at Google Image Search results for “Frida Kahlo painting,” I had no way of recognizing all that we shared: a turbulent relationship with the self, a joint experience in Latina culture, and a queerness.

Kahlo and Rivera’s partnership, though doubtlessly passionate and sincere, was troubled and often in fragments. Both artists had affairs – the bisexual Kahlo with the likes of Josephine Baker (as well as a handful of other male and female suitors) and Rivera with her sister, Christina. They shared a love for one another as well as a disdain, mutually, for the other’s infidelity.

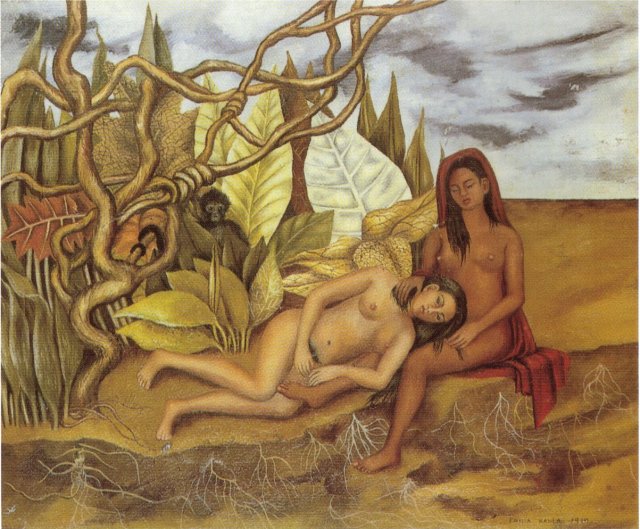

Although we studied Frida Kahlo extensively in school – a strange experience that I recall fondly as the first time I was given license to admire a woman in class – there were specific things we discussed. We went over and over the accident, talking about how her body had been impacted and affected, the pole which drove through her abdomen. We spoke about her marriage, about her divorce and her remarriage to Rivera and her inner struggle to establish with him a familial life she had been robbed of even fantasizing about. But we never spoke about her bisexuality, never discussed that maybe Kahlo was painting about her experiences being in love with women, that maybe Kahlo was painting about her experiences being somewhat trapped in a culture she preceded sexually, in a stagnant and flat world for women as a “women painter,” eclipsed by her husband yet so strong and so loud on her own. They never told us in school that Kahlo was bisexual and I feel conned by that, feel robbed by it.

I’m proud of it.

Although many artists ultimately rely on their experiences to produce pieces, Kahlo is different from all of them. Her uncontrolled self-reflection, her violent self-imagery, her very direct and frank openness about herself, and her use of herself as a subject in her work so frequently makes it impossible for us to parse her person from her creations. Frida Kahlo’s life was her art, paintings of her stuck in her bed or staring directly at us. That canvas was the closest she ever got to being truly free, to experiencing life as a blank page instead of a set of consequences. Is it so much to think, then, that her sexuality is in her brush? That somehow, somewhere, at some point, her art was inconceivably important to her self-expression as a bisexual woman who engaged in woman-to-women sexual relationships is not difficult to believe.

Frida Kahlo’s Two Nudes in a Forest (1939)

“I hope the exit is joyful,” Kahlo once wrote in her journal, “and I hope never to return.” It was 1954, and she had just turned 47. Months later, she died. She passed on July 13, 1954. It was on that day in which Diego Rivera realized the magnitude of his love for her, despite two marriages and a history of affairs. Kahlo was remembered, culturally, first and foremost as the wife of a famous painter. In the eighties, she would be allowed finally to come into her own as an artist and have independent fame and success. It would, of course, be too late.

It’s been a short period of time, then, between Kahlo’s original widespread recognition within the American art world and her subsequent heavy fame worldwide. Her name now is not unfamiliar even to American schoolchildren; she stands as one of the most widely recognized female artists and visionaries from this planet. Frida Kahlo used to be eclipsed by a man and now she outshines many people in her field, dead or alive. Her voice was simply too loud and her story too unique. We had to listen.

Kahlo indulged shamelessly in art as a healing and coping mechanism, and never shied from telling her own stories and using her own life as a vehicle for creation. That act, in and of itself, is so typically female: to feel universal, to want to share an experience with someone else. We remember her fondly as honest and dark, unafraid to confront her own truths and show us our own in the process. We feel sorry for her together, we wonder in our minds what it was like to live with so much pain and only this one outlet with which she must share herself with all of us. But we love her as well – we ultimately worship her and choose, over and over again, to keep her alive.