I used to really like movies. I wanted to make movies. I went to a lot of movies, talked about movies, thought about movies, spent money going to movies, felt affected and defined by movies, particularly movies about girls, which there were always plenty of, including the ’90s movies that probably made you gay, these girl team movies and about twenty queer girl films. I worked annually at the Ann Arbor Film Festival in exchange for free admission, saw everything that rolled through the art house theater and loved New York City because every independent film I wanted to see came to New York.

But for the last six years or so I’ve not been to many movies. I’ve blamed myself for this lapse in dedication. I’ve been too busy starting my own business or going insane, I haven’t been able to carve out two hours to sit and watch a thing — but lately, I’ve been taking steps to insert more “leisure time” into my life.

“I need to go see more movies,” is a thing I say to myself. “I never go to the movies. I miss movies.”

Sometimes I say it out loud to a romantic companion: “We should go to a movie” or “we should see a movie.”

I’ll think, “I haven’t seen a movie in so long, I’m sure there are hundreds of movies to catch up on!”

Then we peruse the movie listings of our local cinema and/or the options available for rental or viewing on any number of online movie-playing situations.

And I cannot find.

One.

Thing.

I Want.

To See.

I’ve been hearing this a lot lately, and duly noted that, like me, my friends blame their decreased attention span for their reduced moviegoing habits.

The media is constantly telling us that the media is ruining our attention span, it’s almost an inevitable self-fulfilling prophecy at this point. But we’ll sit through television-on-DVD marathons, watch documentaries all afternoon, play video games for hours and watch Fight Club 26 times. Many of you might even read this 3,000-word article all the way through. Listen: if Memento, Almost Famous, Traffic, High Fidelity and Bring it On (all 2000 theatrical releases) came out tomorrow, you bet I’d make time.

I endeavor to suggest that it’s not us, it’s them — we’ve skipped the movies for five years because recent theatrical releases just haven’t been worth making time for. I mean, look no further than Julie & Brandy, our in-house movie-reviewing team, which so far has hated every movie they’ve seen besides The Runaways.

What WILL we make time for? Last year, I made (on-demand) time for The Runaways, Howl, For Colored Girls, Black Swan, The Kids Are All Right, and The Social Network. Many people I’ve talked to found the latter two didn’t live up to the hype, why so much hype about those two movies? They were good, but not fantastic.

True enough, but it had been such a long time since I’d seen a new movie about people. In a year clogged by massive computer-enhanced IMAX 3-D movies and giant historical epics, those two movies were primarily about how people got along with other people, in love or at work — and that’s very rare these days.

+

Why Don’t I Like Movies Anymore?

Based on a completely unscientific poll of my own thoughts, feelings and preferences, I’ve surveyed the evidence, done the research, and have the following reasons why:

1. No movies about women.

2. Movie studios/mainstream audiences favor lots of big-budget effects-laden megablowout thrillers over movies about people.

+

When Did I Stop Liking Movies?

But you’re an adult now! You must be thinking. You’re not moviegoing because you’re too busy/poor! But if I was too busy/poor, I’d still WANT to see movies, I just wouldn’t actually do it because of aforementioned business and poverty.

Yes, the younger you are, the stupider and more bored you are, and therefore the more willing you are to give up two hours of your life to the possibility of Batman Forever. As you age, you refine your taste and plan moviegoing accordingly.

I’m sure I watched ten thousand movies a year in my youth and therefore this graph, which I’ve constructed in order to pin down when precisely movies started to suck, begins in 1999, the year I turned 18.

Something changed in 2005, in which I saw only two films in the theater — Rent and Me and You And Everyone We Know. In 2006, I saw Dreamgirls, Borat, Short Bus, and, because my lovely friend Haviland made me; The Break-up. 2007 — just Juno. In 2008 I had a ticket for the midnight showing of The Sex & the City movie, cried my eyes out at Milk, and took my then-girlfriend Alex on a date to Rachel Getting Married. I didn’t see any movies in 2009. For Alex’s birthday in 2010, we got high and saw Alice in Wonderland. In June, Crystal made us all go see Twilight. That’s my half-decade in film.

Now that I’ve Netflixed or downloaded The Social Network, Black Swan, Up in the Air, The Runaways, Whip It! and The Kids Are All Right, I feel pretty much caught up on the past five years. Oh, we tried to watch Inception but fell asleep, it seemed like a demo reel for a very talented special effects guy.

Past half-decades weren’t like this!

Were I to attempt to recap 1995-2000, I’d beat my cumulative 2005-2010 viewings in 1995 alone — Clueless, Boys on the Side, Welcome to the Dollhouse, Mallrats, Now and Then, How to Make an American Quilt, Hackers, Too Wong Foo Thanks For Everything Julie Newmar, Kids, The Basketball Diaries, Toy Story, Apollo 13, Dangerous Minds — jesus. I could go on. ALL IN 1995! (Empire Records came out that year too).

Even solid movies like 2010’s The King’s Speech, which win awards and are universally appreciated, remind me of this quote from Run Lola Run director Tom Tyker: “You are seeing films that are so perfect you don’t even connect to them anymore.”

I miss movies that feel, no matter how large the room or the audience, like they were made just for me. Does anyone else feel this way?

Over the last five years, Hollywood has successfully and increasingly employed digital backlots, photo-realistic CGI humans, 3-D vision, performance capture animation, image-based facial animation, sub-surface scattering, instant motion-capture-to-CG and filmed entire movies in front of green screens, filled in later by CGI effects. Who needs character development when you can turn Sigourney Weaver into a blue computer person?!

+

A Brief History of Movies

Before I continue — a teachable moment. A long long time ago, most movies sucked. Many tend to judge the cinematic past by its few surviving relics, but really history filtered out the crap for us. When the invention of the teevee enabled Americans to watch as much crap as they wanted to right at home, weekly movie attendance plummeted, from 84 million during World War II to its all-time bottom of 17 million in the 70s.

Then, something fantastic happened! The 60s and 70s were an era of unprecedented social upheaval, and that, along with other factors like ‘the invention of film school’ contributed to film taking on a new, equally viable, role in American life:

It was a “perfect storm” of circumstances combining to produce one of the most creatively fertile periods in American commercial movie-making: a new breed of production chiefs trying to save their faltering studios by gambling on an incoming generation of artistically ambitious talent, and a receptive audience hungry for the dramatically provocative, thematically relevant, and stylistically daring, all happening within the context of a society gripped in a painful period of self-questioning and re-examination.

In other words, film became an art as well as a significant element of youth culture.

Then. In 1975, the blowout success of Jaws offered a glimpse of the future — a future in which one film could have universal appeal and make ten gazillion dollars internationally. The 1977 Star Wars trilogy confirmed Jaws was not a “nonrecurring phenomenon.” Back then, however, one blockbuster had the whole summer to itself. Over the next few decades, studios restructured financially and marketing people started gaining more decision-making power than the creatives.

Which brings us to today.

+

1. The Blockbuster Problem

Various evils assembled to create today‘s perfect storm, including but not limited to the rise of the MPAA’s power/censorship, an increasing focus on international markets, pressure on DVD sales and merchandising tie-ins, the recession, a “lack of ideas,” soaring marketing prices and a ridiculous focus on opening-weekend numbers.

This is very problematic for me specifically because as you’ve probably picked up, I’m one of an apparent minority of moviegoers who skip thriller/suspense/action films. I hate violence and I find special effects distracting.

Aside from the big-budget blowouts and the franchise films (Twilight, Harry Potter), movie listings lately have been chock full of action/suspense/thriller movies with names that mean nothing to me and posters that all look the same. Scanning some lists from the last few years I see piles of meaningless words: Red. Iron Man 2. Unthinkable. Death Race. Punisher. Transporter. Outlander. The Righteous Kill. Rampage. The Warrior’s Way. Tracker. Dead Snow. Insidious.

What the hell? These movies are like houseplants to me. I literally don’t see them. My eyes do not bother to register their existence. Thus my houseplants always die and I never go to the movies.

Predictably enough, the genre I’m most endeared towards is independent films, which is more or less the opposite of the blockbuster. I basically moved to New York City in 2000 and 2001 to see these movies — movies like George Washington, Welcome to the Dollhouse, Run Lola Run, Being John Malkovich, The Opposite of Sex, Buffalo ’66, All Over Me, Bully, Lost In Translation, Short Cuts and anything starring Parker Posey. Independent film, however, is one of many casualties of the recession and the Blockbuster Explosion and so are the theaters that used to show them.

That being said, I wasn’t mad at the blockbusters of yesteryear — I too loved Jurassic Park, Independence Day, Titanic, Forrest Gump – in How the Blockbuster Ruined Hollywood, Bil Mesce explains the financial impetus for the increasingly powerful blockbuster model, and its reliance on the “thriller” genre:

The life-sized, resonant thrillers of the 1960s/1970s have been replaced with a steady output of live-action comic books, drowned in the fantastic if not outright fantasy, and their richly shaded life-sized heroes replaced by pure-of-heart superheroes or similarly larger-than-life protagonists. With their breathless pace and non-stop action, there is little room for character, texture, or layered plotting. In fact, such hyper-energized constructs force plotting and characterization toward easily and quickly digestible clichés and predictable forms. Commitment to projects is based not on a passion for the material, but on a calculation of how many toys might it sell; how well it might play in Japan; how easily it can be condensed into a catchy 30-second TV ad. The cinema of ideas…Is long dead and gone.

The price of making these movies is astronomical. I couldn’t sit through Avatar because thinking about its budget w/r/t world hunger made me so angry.

But it appeals to apparently the only demographic of interest, as BitchBuzz recently noted:

“[Hollywood moguls seem unable] to see women as anything but window dressing for the male audience, that mythic demographic that’s supposed to guarantee success. Hollywood has pinned its hopes on that 18-36 male group and aimed most of its fare toward them.”

Which Brings me to…

+

#2: Female Trouble

It was the conversation around Anna Faris‘s What’s Your Number and the just-released comedy Bridesmaids that got me thinking about writing this article. Namely, two specific quotes I read (in print) a few weeks ago:

1. Kristen Wiig, Entertainment Weekly:

“I’ll be happy when the day comes when people don’t think it’s such a big deal to have a movie with a lot of women in it.”

2. Tad Friend, author of Funny Like a Guy: Anna Faris and Hollywood’s woman Problem (in which Faris is called “Hollywood’s Most Original Comic” and apparently is the woman upon which the future of our species depends):

“[Faris’s next film] is an R-rated comedy that’s ‘female-driven,’ meaning that it’s told from a woman’s point of view, and that’s always been a tough sell. Studio executives believe that male moviegoers would rather prep for a colonoscopy than experience a woman’s point of view, particularly if that woman drinks or swears or has a great job or an orgasm.”

Really? A woman’s point of view? A tough sell? Since when?

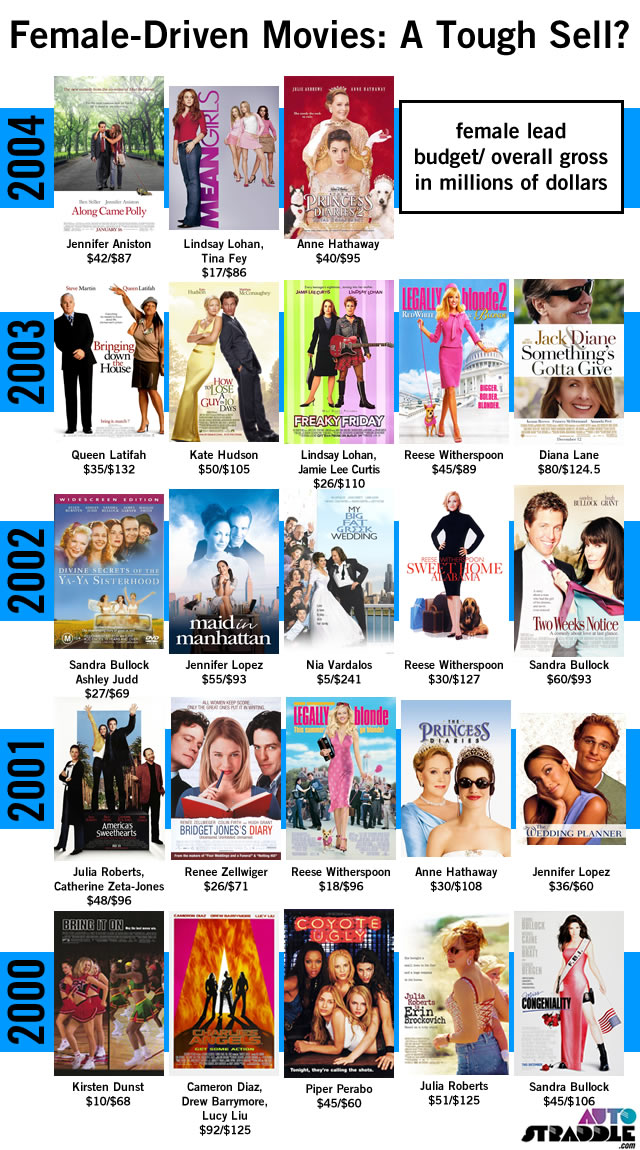

I had my intern make this graphic for you:

Oh! 2005, I guess. I mean, it’s a TOUGHER sell, sure, but are my retrospective nostalgia-tinted glasses playing tricks on me, ’cause I’m worried that “the time when it wasn’t a big deal to have a movie with a lot of women in it” is easier located in our past than our future.

Oh! 2005, I guess. I mean, it’s a TOUGHER sell, sure, but are my retrospective nostalgia-tinted glasses playing tricks on me, ’cause I’m worried that “the time when it wasn’t a big deal to have a movie with a lot of women in it” is easier located in our past than our future.

As is extensively detailed in Ann Hornaday’s 2009 article from the Washington Post, Women & Film, it wasn’t always like this. It’s never been good, but it’s rarely ever been this bad.

In her article, Hornaday goes into some of the logistical reasons for this transformation: when studios became subsidiaries of multi-corporations responsible for contributing to quarterly bottom lines, there was a new/different pressure on studios and thus we no longer see “1970s/1980s/1990s stars like Jane Fonda, Barbra Streisand, Sally Field and Goldie Hawn… making movies in a diverse number of genres.”

A quick perusal of the top 250 films on the imdb list cemented my hypothesis — in 1999, 56 of the top 250 films included female leads. In 2009 — 34.

Would you like a graphic? OF COURSE YOU WOULD!!

These are 1999’s most popular movies with female stars in primary/secondary roles:

…and these are 2009’s most popular movies with female stars in primary/secondary roles:

At some point in the mid-00s, women got ditched and then told that it has always been so. This became ‘official’ in 2007 when Warner Brothers President of Production Jeff Robinov allegedly made a new decree that “we are no longer doing movies with women in the lead.”

This is especially bad news for queers — of the 38 highest grossing LGBT films produced between 2000 and 2009, only TWO were produced post-2005, and they were guy movies — Brokeback Mountain and Milk. Also the best lesbian film ever, The Nicest Thing, hasn’t yet been done, girl.

In The New York Times‘ “Women in Hollywood 2009,” Manhola Dargis points out that Sony Pictures Entertainment’s Amy Pascal, Hollywood’s sole female film studio chair, was making movies “like “Little Women” and “A League of Their Own” [in the 90’s]. In recent years, however, Sony has become a boy’s club for superheroes like Spider-Man and funnymen like Adam Sandler and Judd Apatow.”

Dargis later told Jezebel that she finds it “depressing” that Apatow “has taken and repurposed one of the few genres historically made for women… [romantic comedies are] supposed to be about] a relationship between a man and a woman, but they’re really buddy flicks.”

Speaking of, I used to never think about gender when picking a movie — I didn’t really HAVE to, because even male-centric films appealed to me — from comedies like Ace Ventura, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Dazed & Confused, The Big Lebowski and Wayne’s World to classics like Good Will Hunting, Dead Poet’s Society or Saving Private Ryan. I loved Tom Hanks, Will Smith, Denzel Washington, Robin Williams, Johnny Depp, Young Leonardo DiCaprio, Ed Norton — and I loved anything made by Robert Altman, Spike Lee or Woody Allen. These days, it’s tough to muster up more enthusiasm for Michael Cera/Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s emo feelings or Vince Vaughn‘s hyper-male hijinks.

This week, Bridesmaids comes out, and it’s positioned as “a referendum on the viability of women in Hollywood comedy.”

I guess these just didn’t cut it?

This weekend, Bridesmaids earned a “better-than-expected debut with $24.4 million” — second, of course, to Thor. Fucking Thor!

The Future

In the 90s there was so much to see I’d sometimes see two in one day, and because I liked weird indie films nobody else wanted to see, that usually meant I was going alone.

In the 90s there was so much to see I’d sometimes see two in one day, and because I liked weird indie films nobody else wanted to see, that usually meant I was going alone.

But also — I remember dashing madly through Times Square on our lunch break from The Olive Garden, cigarettes furiously fuming into the crowded greasy air, running up the eight sets of escalators in the AMC just to catch 75% of The Anniversary Party before the dinner shift started up. I remember walking to Harlem late at night to see Girl Interrupted because crying at home was getting depressing.

My favorite part of the Sex and the City movie is that it was the first time in years I’d participated in a “mass coordination of friends to see the same film” situation. I used to like that a lot. I liked it enough to almost enjoy Twilight: Eclipse, just ’cause I was there with my friends and it was a thing.

In 1999, Entertainment Weekly boldly declared that “1999 will be etched on a microchip as the first real year of 21st-century filmmaking.” It’s a fantastic article, full of hope/dreams about a “new age of cinema” and “really exciting young artists who have their own voices.” Thanks to films like Being John Malkovich and Pi, agents aren’t afraid anymore to send “that odd, quirky type of material” to film studios! Stars like Cameron Diaz, Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise aren’t afraid to take bets on movies like Eyes Wide Shut, Fight Club and Magnolia!

At the article’s end, director Bennett Miller counters the pieces’s thesis with a pretty adequate prediction:

“I think there’s going to be this wonderful, explosive glut of mediocrity. It’s going to be horrible. You know, big ideas without a lot of preparation. The technology invites a certain carelessness, because it’s easy to let your guard down and not be disciplined.”

And so it is.

Yes, it was exciting to suddenly garner laptop access to a bajillion movies, and it was very exciting to be able to live our entire lives on a tiny Blackberry phone, but those innovations have been around just long enough that I, for one, am over the novelty of it. Movies are best enjoyed in theaters, period.

These days when I stare at a screen, it’s for a television show or a documentary — I’m doing True Blood right now.

I’m not staying home because I’m lazy, distracted by technology or under-appreciative of the group-movie-watching experience, or even because movie tickets are expensive.

I’m staying home ’cause the stuff showing on my laptop is just so much better than the stuff showing on your screen.