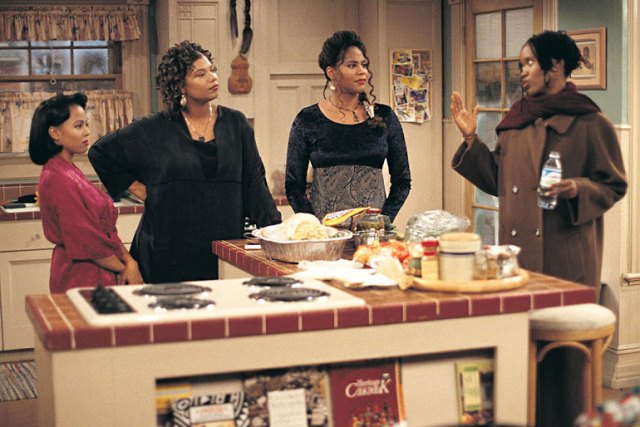

Living Single, the quintessential sitcom of the 90s — at least for Black women — was finally added to Hulu’s online streaming in January. Rejoice and binge!

In an era of cash-grab reboots and seemingly-identical multi-camera sitcoms lacking identity or, apparently, purpose, it’s comforting to return to one of the OGs. Living Single created the tropes that now saturate TV, but pleasantly, over 20 years later, it still holds up.

The ’90s were chock-full of incredible Black sitcoms: A Different World, Family Matters, the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and my personal favorite as a young person, My Brother and Me, showed for-the-time diverse representations of Black life. In retrospect we can see that it’s overwhelmingly upper/middle class, cis, straight Black life, but at least we weren’t all in poverty or just sidekicks, tokens, and/or comic relief. Living Single was also the very first primetime comedy developed by a Black woman, Yvette Lee Bowser!

And it shows. A perfect example of 90s Black feminist media, the show makes plain its message and aesthetic with its theme song, performed by Queen Latifah — who also plays main character Khadijah, in one of her first major acting roles. “I]n a nineties kind of world/ I’m glad I got my girls/…Whenever this life gets tough, you gotta fight/ With my homegirls standing to my left and my right.”

The series focuses on the professional, personal, and — especially — love lives of four single Black women in their mid-to-late 20s as they attempt to find fulfilling relationships and career success in New York City. Living Single premiered in 1993, a year before Friends, five years before Sex and the City, and long before Girls. All of these shows (and so many others) are about a group of single professional women in a big city, and all of them borrowed Living Single’s premise —except with all-white casts). Living Single also premiered years before the Spice Girls brought “Girl Power” to the masses and ushered in a mainstream ’90s feminism that owed a lot to the show.

Looking at Living Single from 2018 is interesting. Unlike many ’90s (and, honestly, 2000s) sitcoms, which don’t hold up because of their pervasive casual misogyny and transantagonism, Living Single seems remarkably ahead of its time and offers meaningful messages that continue to resonate.

Knowing what we now (sort of) know about Queen Latifah, I was excited for a rewatch to see whether any lesbianism would work its way to the surface. While Latifah has played straight characters for most of her career, it’s a little disappointing in retrospect to see main character Khadijah join her peers in pining over men (who, true to ’90s Black mainstream media tropes, all appear to be ain’t shit). However aggressively heterosexual she plays her character, though, something that’s so refreshing about Living Single is how resolutely these women choose their friendships over their relationships with men.

Well, most of the time. As early as the second episode, Maxine and Regine have a falling out when Maxine dates Regine’s ex. By the end of the episode, though, they resolve to always prioritize each other and to never let a man get between them — unless he’s “really fine,” of course, then “all bets are off.” It’s funny in context, especially given the cackling that follows. And the next scene sees them all in pajamas, gettig ready for bed and singing about how much they love each other.

This factor is a consistent joy throughout the rewatch. The women have wildly different opinions about the issues they face, and butt heads often, but always seem to respect each other. A common thread in contemporary sitcoms is that writers and producers seem to confuse being mean with being funny. Khadijah and Regine, especially, rib each other constantly, but you can always see that the love is there. This is something that Black people will immediately recognize — it’s called “signifyin’” or “playing the dozens” — but something non-Black communities seem to struggle with.

Consider this scene from Friends:

Ross insults his sister, and though she’s smiling you can tell she’s upset. She decides to fire back at everyone else in the room by mentioning what might be their most embarrassing experiences, and the looks on everyone’s faces show that they’re shocked and bothered. Monica runs out of the room. (In the same episode: Joey punishes Chandler for kissing his girlfriend, who he was emphatically not exclusive with, by locking him in a huge wooden box; and Ross continuously badgers Rachel over something minor and turns it into an emotional fight despite it being Thanksgiving dinner and Monica having a date at the table). Regardless of the title of the show, they don’t seem like very good friends.

But on Living Single, it’s clear that the characters are in it for each other. In the third episode, the crew finds out that Synclaire hasn’t been on a date in a while. Regine resolves to set Synclaire up, and in the process teases Khadijah about her lack of a love life. Khadijah fires back at Regine for “giving it away with a double coupon” — sex shaming Regine, and not for the first or last time — but Regine smiles and shrugs in response. At no point does this back and forth feel nasty. They’re just teasing each other, and love each other, and this is shown by how, when it matters, they consistently have each other’s backs.

They also consistently laugh at each other’s jokes, something I didn’t realize was missing from other sitcoms until I rewatched this one. Their smiles and laughter are proof that they’re not just throwing insults at each other, they’re exchanging jokes with each other. The difference is crucial.

The girls regularly trade the role of butt of the joke — Regine gets back at Khadijah a bit later, when Khadijah asks Synclaire whether she wants to be hooked up with “some sorry excuse for a date,” or whether she want to “run her own life.” After a pause, and with a huge smile, she exclaims, “I want a date!”

Regine has a lot of sex, and though the other girls rib her for it, they don’t look down on her (unlike on Sex and the City, wherein Carrie sleeps with a new guy every episode but still can’t seem to resist sex-shaming Samantha constantly). Khadijah is often positioned as the moral center of the show, but she also validates the other girls’ positions when they diverge from her own. Khadijah seems to want Synclaire to be more like her — self-possessed and independent — but as soon as the others start setting Synclaire up on her date, Khadijah doesn’t interfere. Neither do any of the other girls — who all seem to want Synclaire to be a high-powered, successful, independent woman like themselves — look down on her for eventually getting together with simple-minded but sweet Overton.

This example also illuminates how the show, like its contemporaries, had to walk a fine line between expressing its feminist message and capitulating to the cultural expectation that success means finding a husband as much as having one’s career ambitions validated. “What would the world be like without men?” Asks Synclaire in the first episode. “A bunch of fat, happy women and no crime,” declares Khadijah. Nonetheless all of the women prioritize dating and relationships at least as much as their careers.

The girls do have careers, though. Maxine is a successful divorce attorney (who brags in the first episode about a case she just won, in the wife’s favor, and positions herself as using her career as a means to right past, sexist wrongs). Khadijah runs a Black women’s magazine with a clear feminist bent. When Synclaire accidentally ruins a Maya Angelou cover story, Khadijah audibles and runs a story exposing men who lie about being married to sleep with and then dispose of women. Synclaire is Khadijah’s assistant, and also an aspiring actress, but also seems content with a simple life focused on interpersonal relationships. Regine does a variety of things. She’s ostensibly a buyer for a clothing boutique, but her primary career seems to be as a negotiator of the patriarchal bargain: using men for their money to promote herself and live the kind of life she wants.

Khadijah, Maxine, Synclaire, and Regine are a fascinating, diverse group that introduced the standard sitcom blueprint with which we’re now quite familiar. Khadijah is the straight-laced voice of reason; Regine is the sexually-charged, upwardly-mobile maneater; Synclaire is the new age, book-dumb, lovable weirdo; and Maxine is the quirky, self-possessed but often single battle-axe.

Also part of the group are their male friends: Kyle, an arrogant but charming stockbroker who mirrors Regine (an early scene where they, in unison, go over the standard “it’s not you, it’s me” breakup speech is gold); and Overton, a simple, earnest handyman who is a foil (and love interest) to Synclaire. And the parade of mostly uninteresting (and largely terrible) men they date throughout the series.

Living Single is more than just the blueprint for future TV sitcoms, however. Like the shows that came afterward, it attempted to validate the experiences of “modern,” career-oriented women and the struggles they face to be successful in their lives and loves. But it did so with something so many of the sitcoms that came afterward lack: heart.

I like my television to be entertainment first and foremost — simultaneously funny, relatable and, well, entertaining. The best shows, however, provide a thoughtful window into deeper aspects of the human experience: the nature of intimate friendship; or the difficulty in navigating a sexist, patriarchal culture; or the paradox of wanting to succeed on one’s own terms coupled with the desire to be validated in spite of that success (or lack thereof). What Living Single did so poignantly was capture these ideas without succumbing to the basest aspects of the human experience, especially when portrayals of women are involved. The put-downs, the jockeying for position in the eyes of men, the insults and backstabbing and cheating and blatant disrespect.

In this way, Living Single stands among the greats, and is fully deserving of a nice, long block of time in your binge watching schedule.