There are chronic discrepancies between public opinion and law on several key gay issues, according to a report released yesterday by the Human Rights Campaign. The HRC found that, while the majority of Americans support equality on a variety of equality issues, legislation doesn’t reflect this. In a press release, HRC President Joe Solmonese said,

There are chronic discrepancies between public opinion and law on several key gay issues, according to a report released yesterday by the Human Rights Campaign. The HRC found that, while the majority of Americans support equality on a variety of equality issues, legislation doesn’t reflect this. In a press release, HRC President Joe Solmonese said,

“While the American people embrace their LGBT friends and neighbors, government remains a lagging indicator of acceptance. The numbers don’t lie. Americans want equal rights for LGBT citizens and lawmakers should heed their call.”

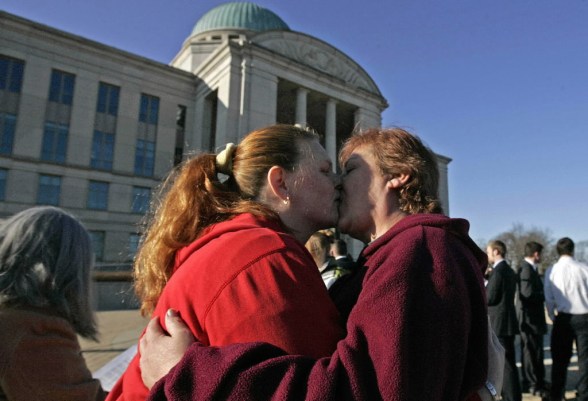

While issues such as workplace and employment discrimination, insurance, and the definition of family are all problematic, the most obvious gap is still over marriage equality.

The following seventeen states now have majority support for gay marriage:

+ Delaware

+ Nevada

+ Maryland

+ Pennsylvania

+ Oregon

+ Colorado

+ Washington

+ Maine

+ Hawaii

+ New Jersey

+ New Hampshire

+ California

+ Connecticut

+ New York

+ Massachusetts

+ Vermont

+ Rhode Island

This doesn’t seem like a lot — and really, it isn’t. But according to research by Columbia University, in 2004, same-sex marriage didn’t have majority support in any state. With that in mind, 17 is much more impressive. If you believe a CNN poll conducted last summer, 52% of respondents felt gays and lesbians should have the constitutional right to get hitched, which means there might be even more states with majority support.

Currently, however, gay marriage is only actually legal in five states:

Massachusetts…

New Hampshire…

Iowa…

Connecticut…

and Vermont!

And, also, the District of Columbia (Washington DC):

However, New York, Maryland, and Rhode Island are considering marriage equality in 2011.

Maryland is currently considering proposals on both full same-sex marriage benefits and on a civil union plan that would act as a compromise. While in the past similar legislation has stalled in committees, both supporters and opponents believe there will be action this year. Supporters point to a younger and more liberal House, the recent appointment of two more Democrat supporters, and the recent DADT repeal as a sign that same-sex marriage will actually happen.

“There’s a magical moment where something controversial has picked up enough speed to pass,” said Sen. Richard S. Madaleno Jr., an openly gay Democrat, in the L.A. Times. “I believe we are there.”

Opponents, of course, point to the changes as a sign of the coming apocalypse, arguing that marriage should be about reproduction and that the legislation will fail and then be put to voters, where it will also fail. It’s that kind of open-minded optimism that’s gotten them this far, I guess.

In Montana earlier this week, a judge heard the first arguments in a case put forward by six gay couples who want civil unions, domestic partnerships, or similar protected status under the state constitution. In 2004, Montana passed an amendment defining marriage as between a man and a woman, so now the debate will center around how this is interpreted and whether the court has a right to do anything about it. The rest will likely focus on the gay-marriage-debate staple of whether a gay couple is a real couple. According to NCEN:

“Another question is whether gay couples in a committed relationship are similarly situated to married couples, which is the basis for claiming the gay couples face discrimination under the constitution’s equal-protection clause.

[District Judge Jeffrey Sherlock] said gay couples in committed relationships face many of the same duties of married couples, such as bills to pay and children to care for.

“Doesn’t that put them in the same boat as people who are married?” the judge asked.

No, [state solicitor Anthony Johnstone] replied. The two groups are separate classes and that’s what the people of Montana meant when they approved the marriage amendment, he said.”

According to polling analyst Nate Silver, by 2016, gay marriage will be legal in most states. His regression model, which looks at which states would vote against a marriage ban based on a) when the last state constitutional amendment was voted on, b) the percentage of adults who said religion was an important part of their daily lives, and c) the percentage of white evangelicals in the state, predicts that only a few southern states will hold out until the early 20s and that Mississippi will be the last one to cave in 2024. When discussing his findings, Silver writes,

“It is entirely possible, of course, that past trends will not be predictive of future results. There could be a backlash against gay marriage, somewhat as there was a backlash against drug legalization in the 1980s. Alternatively, there could be a paradigmatic shift in favor of permitting gay marriage, which might make these projections too conservative.

Overall, however, marriage bans appear unlikely to be an electoral winner for very much longer, and soon the opposite may prove to be true.”

As Dan Savage wrote in a recent op-ed in the New York Times,

“Social conservatives long to raise their children in a country where they don’t have to hear about homosexuality every time they turn on the news. I’d like raise my son in a country like that too. And guess what? In countries like Canada — where the fight over gay rights is essentially over, where there is gay marriage, open military service and employment protections — homosexuality hardly ever makes the front pages of newspapers. There’s nothing much to report.

Conservatives can’t get rid of us, but they can hear less from and about us. They just have to bend toward justice.”