George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual. We will be celebrating Pride as an uprising. This month, Autostraddle is focusing on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. We’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

Author’s Note: This article is primarily to help white people talk to other white people about racism and white supremacy. Non-Black people of color will likely find it useful as well. Black people: unless, like me, you have white family members, this is probably not your job. Read on if you like, but I never do this kind of labor for free and I don’t suggest you do either.

One of the most powerful ways you can be a part of the current uprising against white supremacy is by having frank, difficult conversations about racism with your white family and friends.

Police violence sparked the latest wave of this movement, but policing won’t change until racism and white supremacy change. Because police violence is part of a system built on white supremacy and is perpetuated and enforced largely through white complicity, it won’t change until a critical mass of your families, friendship circles, institutions, and hearts are no longer complicit.

Your job is to be a part of building that critical mass within your sphere of influence. It’s not enough to not be racist. You have to be actively anti-racist, which means using your relationships with other whites — many of whom are recalcitrant and resistant to change — and working on changing them.

It will be difficult. They may not want to listen. You may end up forever poisoning your relationships with your racist relatives. But it will be worth it. As Allyn Brooks-LaSure (and countless others) have made plain:

“If courageous people of color can brave dogs in Birmingham, horses and billy clubs in Selma, fire bombs in Florida, tear gas in Ferguson and Minneapolis, lynch mobs in Georgia — then well-meaning white people can brave awkward conversations on family Zoom calls, in work conference rooms and at Thanksgiving dinner.”

Also, you’re not in it alone. Here are some tips, tricks, and suggestions for making it happen, from someone who trains people on the basics of privilege and oppression professionally and has a degree in persuasion (really). You can do this!

How to Talk to Your White Friends and Family About Racism

1. Prepare — A Lot. And Check Your Expectations

Read this article, and then read 10 more like it, and then 10 books. Do a ton of research. Especially read Black people’s ideas and perspectives. Have a stack of links to reputable sources outlining hard data. Here’s a place to start.

You also might need to check your expectations. Some activists argue that now is the time to make white people uncomfortable, that we shouldn’t coddle them, that y’all need to be confronted with the harshest truth of your complicity in racism. I agree that y’all don’t deserve to be coddled or have your hands held through this process. But in my experience, that’s the only way for the vast majority of white people to actually shift. You can’t get people to agree to be part of a solution until they agree that there’s even a problem to be solved.

People’s minds are rarely changed when they are confronted with a lot of information that conflicts with what they already know and/or believe. They usually have to be guided carefully and gently out of their comfort zones, hands held by someone with whom they have an existing relationship, toward understandings that conflict with their current beliefs.

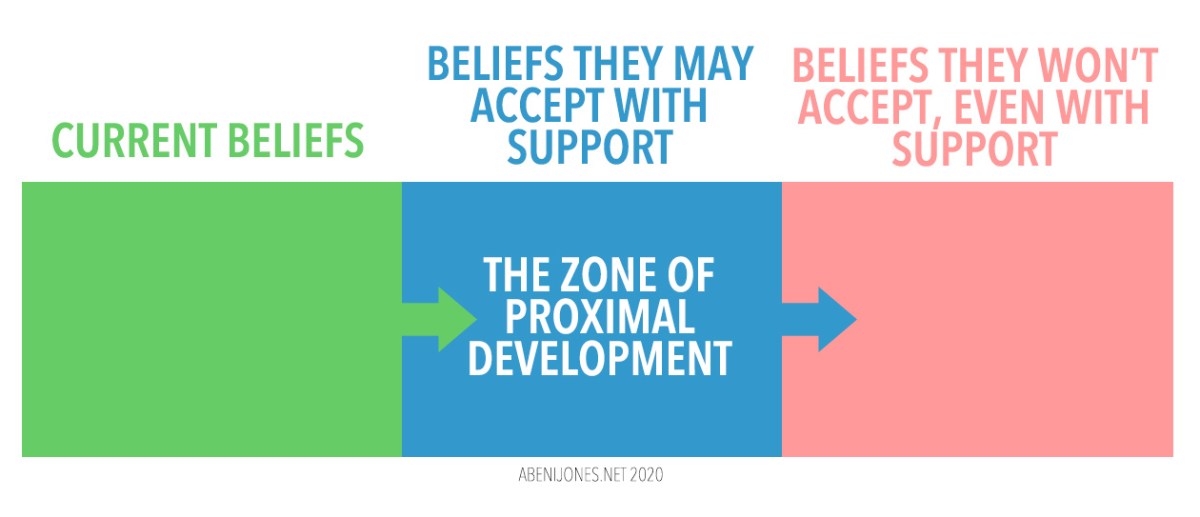

When I was in graduate school getting my teaching credentials, we learned that children have a “zone of proximal development,” or ZPD. I think it applies to adults too.

First are the beliefs someone has currently. Then, the beliefs they can come around to with support (their ZPD). And finally beliefs they simply won’t accept right now, even with support. You can’t get them to jump from the green zone (racial hatred is bad, maybe) to the pink zone (I am complicit in and need to fight systemic racism). You can, possibly, get them from green to blue (racism is widespread in American societal institutions) though! And then, maybe what was once a pink idea can become a blue one. Their ZPD keeps moving as their beliefs do. It would be incredible if you were able to radicalize the adults in your life, but it’s very unlikely. You can, however, get them to recognize that racism is real, is a systemic problem, and maybe even that they should do something about it.

The point is, with support, most people can accept new beliefs, as long as they’re not too far a leap from what they already believe. But they need support. You’re that support. This will be emotionally taxing. Nobody likes hearing negative truths about themselves; they will likely resist and it will be frustrating. But it’s crucial.

That’s also why this is your work, not ours. If you’re quick to anger, like to interrupt, or need to be “right” or to “win,” those approaches are unlikely to work. This is going to be a marathon. It will go slowly. You’ll need to be satisfied with baby steps, especially at first.

2. Some Basic Tactics and Reminders

Be as empathetic, compassionate, and kind as you can—take breaks or change topics when you can’t. Don’t have this be the only thing you talk to them about. Try not to get angry or yell. Statements like, “I hear what you’re saying, but have you considered…” or “It sounds like you’re worried about / afraid of / trying to say …” can build rapport and lower defenses, which you need. Guilt is a huge barrier to learning; it tends to shut down critical thinking and puts people into defense mode, where it’s very difficult to learn. You will have to concede some things, leave some things on the table, and tentatively agree (or refrain from disagreeing) with some things in order to make a point and find common ground.

Repeat their own words back to them, ask clarifying questions, and/or rephrase what they said and ask if that’s right. Make them defend their own words instead of disagreeing outright! Watch your tone, though; be genuinely curious.

Control extrapolations. Don’t let them get too ahead of themselves. Just like supporting “gay marriage” doesn’t mean supporting bestiality or whatever, acknowledging that George Floyd should be alive doesn’t necessarily mean you hate all white people. If they start extrapolating too far, don’t get sucked in. That’s a rhetorical control tactic. Bring the conversation back to what you were originally discussing.

Be generous! If they concede a point, allow it. Maybe even celebrate your agreement! This is not about winning or being right, it’s about graciously and slowly moving their understanding in the right direction. Small wins are still wins.

You may have to depersonalize things as much as you can, at first! They might not be ready to be implicated yet. Eventually you can help them see how they’re part of the problem, but if that’s not in their ZPD, then don’t force it too early. Eventually, use examples from your own life to show them that being vulnerable and admitting your complicity in the system is OK.

Focus on slam dunks. If they bring up something that’s tricky/nuanced, you can defer. “You know, I want to look more into that, because that doesn’t seem right but I don’t know enough about it yet” is fine! It can also be useful to use this as an opportunity to learn together: “Hmm, do you want to read an article or two about that with me?” You also can’t prove that “a white person wouldn’t have been treated this way.” For now, stick to things you can prove, like disparities in traffic stops, drug arrests and convictions, housing, hiring, and banking, where plenty of studies have compared people who are “equal on paper” but are treated very differently.

Did you already have to have a conversation with them about oppression based on gender or sexuality? You can build off of that. What worked then? Racism is NOT the same as transphobia or homophobia, so don’t make a complete equivalence — but there are many similarities they might be amenable to if they came around on those issues.

3. Build On Their Values And Beliefs

Values, largely unchangeable by adulthood, are the foundation upon which a successful argument must be built. Your goal is to help them to realize that racial justice already aligns with their values, not to get them to accept new ones. What’s important to them? If you can identify their values, then you can build from there.

Adults also have core beliefs about race and racism. These aren’t as strong, because they are learned — and thus can be unlearned. You will likely hear some of them come up in the course of your conversation. If you hear one, that’s another great opportunity to connect and build.

Here are some common values and core beliefs about race that can impede someone from accepting anti-racist ideas. Find a place of agreement and commonality and build from there.

Values you can somewhat agree with and build off of:

Strict law and order is essential for a functioning society

Agree that things like due process are important. Build by discussing how George Floyd, Eric Garner, and other Black people who may have committed a crime deserved a fair trial, not the immediate extrajudicial death penalty. You can even eventually get to things like disparities in sentencing, qualified immunity, corruption in courts like in Ahmaud Arbery’s case, and more (especially if you have local examples).

Ownership of property is an unalienable right

Agree that people should feel safe in their homes and be able to defend them. This one is especially relevant to critiques of “looting.” Build by talking about people like Breonna Taylor, or things like the MOVE bombing, or Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, or Seneca Village, or the Wilmington Massacre. Talk about how most property owners today have insurance, and how property can be rebuilt but lives can’t (if you use one of those examples, it also might be worth mentioning how Black property owners frequently DIDN’T have insurance, because insurance companies refused to insure them. This persists to a degree today as well).

Truth and/or facts are more important than feelings

Agree that facts are important, and have some at the ready. This is usually where people quote crime statistics (usually wrongly and from memory). Build by using actual facts — remember to focus on slam dunks. If they insist on talking about crime, there are facts disproving “Black-on-Black” crime myths, but you might be better off going back to talking about due process.

We’re all human and/or colorblindness/tolerance is an important virtue and/or love is stronger than hate and/or we should focus on what we have in common, not how we’re different

Agree that we are all human, love is powerful, and we have a lot in common. Build by asking if they believe that American society operates with these values by actually treating us all the same. If they say yes, use some of the facts you researched above to show this isn’t true. If they say no, then ask whether we shouldn’t honestly acknowledge this reality and work to make this true in society, not just in our hearts.

America is a meritocracy i.e. If you just work hard, you’ll get ahead

Agree that hard work is important and should be rewarded. Build by asking if they believe America has always been a meritocracy. If they say yes, ask them about slavery. If they concede that America hasn’t always been a meritocracy, but is one now, then you can go to “Racism is a thing of the past” and build from there.

Everyone should just be treated equally

Agree that everyone should be treated fairly and justly. This is a place where you need to know the difference between equal and fair, but it might not be time to get into that yet. Similar to “We’re all human,” ask whether they believe society currently treats everyone equally. Build by using your research.

Riots don’t help progress; protesters need to be more patient, nonviolent, and respectable like MLK

Agree that riots could potentially turn off some allies. Build by talking about or sharing the Martin Luther King, Jr. speech in which he says: “The riot is the language of the unheard,” especially if they name drop MLK. While not in complete support, he was sympathetic. Ask whether they believe that protestors’ anger is justified, if not their tactics. If so, focus on THAT and build. Ask, perhaps, what the appropriate response is after years of nonviolent protest and little to show for it? To keep asking nicely? It also might be worth noting that after six days of rioting and tens of millions in property damage following MLK’s murder, the 1968 Civil Rights Act was passed. Look into how much has been accomplished in the last few weeks because of the uprising.

Core beliefs you can slowly shift through compassionate conversation:

Racism is a thing of the past or happens elsewhere

Agree that things have gotten better in some respects, and things are different in some places. Build by pointing to some of the slam dunk facts you researched, especially if you have local examples. It can also be useful to ask them when exactly they think racism ended, and whether there’s been enough time to eliminate its lasting effects on society since then. If they concede that not everything is better, you might build by asking: what is the appropriate level of racism to have in a society? When is the right time to stop trying to make things better? Whose responsibility is this work?

Individual racists are terrible, but you can’t blame a whole system because of a few “bad apples”

Agree that police forces, universities, HR departments, hospitals, schools, and other institutions have “bad apples” within them, and individual racists should lose their positions of power. See if you can get them to agree to that point, and if not, try discussing that first. Build by asking whether someone can still be considered “good” if they have power to stop “bad” people from doing bad things but choose not to. Ask what percentage of a group has to be “bad” before it’s acceptable to write off the group wholesale. Muhammad Ali’s statement about rattlesnakes might be appropriate here, or James Baldwin’s explanation of institutional racism on the Dick Cavett show.

I don’t personally hate Black people, so I’m not part of the problem

Agree that they don’t personally hate Black people. Build in a similar way to “Bad Apples” by talking about bystanders; using the example of the other three cops who didn’t prevent George Floyd’s death could be useful. Maybe, talk about a time someone told a racist joke and you didn’t challenge them, and how by not saying anything they likely thought you were agreeing with them. How you felt like part of the problem. Don’t they think people who allow racists to do their thing without challenging them are part of the problem?

4. Ask Questions, But Don’t Interrogate

So far I haven’t mentioned how to actually start the conversation. Your best option to start is just to ask questions, and you should continue doing that throughout. Try your best not to pontificate. “What do you think about these protests going on?” or “Did you read what Obama said?” Could be a good start. Or you can foreground your own feelings: “I’m so sad about what’s going on and I’m not sure what to do.” Then let them respond and see where they go. Asking questions, and giving them time and space to figure out answers to them without telling them what you think or believe (unless you’re asked) can be very effective.

Simply asking them to explain what they mean by the things they say, and asking follow-up, clarifying questions, can be very disarming and reveal beliefs they don’t even realize they hold. Try to remember the following, though, to prevent it from becoming an interrogation. If people feel like you’re asking biased or loaded questions, they might put their defenses up. That’s not what you want.

You’re not an expert.

Unless you’re Black, at a certain level you can’t truly understand what’s going on or what this is all about. This is an opportunity for y’all to both learn some things. This includes conceding points and trying to get to the truth, not winning the argument. No matter how many articles you read to prepare for this, you’re not an expert. Be humble.

Keep it conversational.

If you have any intention of having a “gotcha!” moment, they’ll probably sniff it out. Try not to even seem like you’re accusing your folks of being racist—for true transformation, they’ll have to come to that conclusion on their own. You’re just having a conversation. You’re much more researched and prepared for it than they are, but it’s still just talking with a friend or family member. There has to be some love or caring present or it will feel accusatory.

Insist on grounding ideas with evidence.

If they say “Well, Black people _______,” ask for evidence. “Oh, I haven’t heard that, where did you read it?” Don’t allow for “conventional wisdom” or “Hannity said.” Don’t allow for anecdotal evidence! Insist on sources. If they don’t have any, it can be useful to say “That’s interesting, because this report I read …” and provide the source. If they don’t want to read evidence that conflicts with their worldview, ask them why that is. If you anticipate this, make sure you find some conservative voices that back up your points.

5. Conclusion

As annoying as it is, probably, to hear it, you really have to lead with love. It’s not our responsibility to love people who hate us or wish us ill, but if those people are your friends or family, it is yours. If you genuinely care about your family and want them to be and do better, let that ground your conversation. If they’re your parents, remember that they raised you and probably tried to do the best that they could — they have just been brainwashed by a system much older, bigger, and better funded than any of us. You’re having this tough conversation because you love them and because you love humanity.

The ultimate goal here might just be for your folks to even acknowledge that racism exists. It might be for them to finally see themselves as complicit in it, and it might be for them to realize that it is their duty to fight against it. Maybe for them that’s voting differently, or donating money, or taking to the streets. Maybe you’ll be able to get them to understand institutional oppression, or embrace socialism, or anarchism, or anti-capitalism. Maybe they’ll realize that the entire system needs to be torn down, and both policing and the prison industrial complex need to be abolished and replaced with community-based alternatives. Probably not, but that’s OK. Regardless, it is your duty to try to get them to move away from denial and complicity and toward allyship and solidarity. Good luck.

Appendix: Some Definitions That Can Be Helpful

Are your family or friends interested in justice and liberation in a general sense, or agree with the ideas of, say, #blacklivesmatter, but seem to miss the mark or don’t see how they’re implicated? Who think being personally not racist is enough? The following might help you get them to the next level.

Appendix 1: A VERY Basic Definition of Racism

Racial Prejudice + Power = Racism.

This basic framework applies to most all forms of oppression, as in the above graphic. It’s very simplified but is easy to understand and convey. The main appeal is that it takes racism out of an individual person’s beliefs and into the realm of power dynamics and systems. It’s not as important whether an individual “is a racist” (though that’s accounted for under “interpersonal” oppression). What matters more is whether the ways they wield their relative power have racist impacts. Baldwin on the Dick Cavett show, again, expresses this well.

Note that prejudice can be implicit — you don’t need to have active racist beliefs to be prejudiced. And prejudice doesn’t just mean hate, it means any generalized judgement based on a lack of information. Literally any belief applied to an entire, diverse race of millions of individual people fits this definition, by the way.

This is also a springboard to understanding why “reverse racism” doesn’t exist. People of color may have interpersonal power, but we don’t have the collective power to enforce and spread anti-white ideologies throughout our culture for centuries or shape major institutions to reflect our prejudice.

The Four I’s — ideological, institutional, interpersonal, and internalized oppression—are important because they get at the scope of the issue. The first one is often left out, but it’s one of the most important. The ideology of white supremacy is baked into American culture and has been promoted and normalized through every media outlet in this country for centuries. If you’re going to discuss these, make sure to research examples of each to show how they function and how they support each other.

Appendix 2: A VERY Basic Definition of Privilege That Can Be Helpful

I’ve found that this is a good framework for explaining privilege, especially to white people who don’t feel privileged or when you’re worried people will feel guilty and shut down.

Privilege is a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group of people. When I teach this, I focus on “special right”— because that’s a contradiction in terms! Rights by definition are granted to all. That means that privilege is when only one group of people has access to something that everyone deserves, or when they’re shielded from something that nobody deserves, because of their real or perceived membership in a certain group.

This is helpful for many who feel, or were taught, that acknowledging privilege would mean they don’t deserve what they have, and might have to give up what they have so that others can get access to it. It doesn’t necessarily mean either of those things (white lives don’t have to not matter for Black lives to matter, for example). Justice would be everyone getting access to the things we all deserve by being human — not that white people have to give those up. See the examples of privilege below to see what I mean.

It can be crucial to let white people know that privilege is not usually their individual fault. When we talk about privilege, it’s easy to put up barriers to understanding because of how uncomfortable white guilt can be. When you recognize that privilege isn’t necessarily your fault, it helps break down that guilt barrier (white supremacy is y’all’s ancestors’ fault, though, but only acknowledge that if it helps, not hinders). Most white people didn’t ask for it, but it still benefits all of you.

I also like to acknowledge that privilege is contextual. White supremacy and anti-Blackness are global, but whiteness carries different amounts of power depending on context and circumstance. I usually teach briefly about intersectionality before this, and won’t get into it here, but regardless it can be a useful point.

I usually give four examples of privilege to help cement people’s understanding (and to create some symmetry with what I said about oppression). Ideological and representative privilege are frequently understood, while privilege of selfhood and privilege of oblivion are rarely. Privilege of selfhood means you are able to be seen as an individual, not just a member of a racial group, and you’re believed when you say who you are. Any Black person called a “credit to their race,” mistaken for waitstaff, or met with surprised faces when they drop their educational or career credentials knows this one.

And privilege of oblivion has been incredibly obvious since 2016, as we’ve seen white women, especially, come out to protest for the first time (even older white women who were around during the civil rights movement). Y’all’s obliviousness to our reality is on purpose, though; white supremacy set the system up so that it’s incredibly easy to never have to confront or care about the reality of racism because it doesn’t affect you in obvious ways. White queers are notorious for this one.

Privilege can be tricky to discuss, but I’ve found this approach helps ease people into understanding it, and then they’re able to go deeper. It’s also useful in supporting people to accept ideas in their ZPD, and then continually supporting them as their ideas shift.