How Sick Is “Sick Lit”?

via lindsaytrevor on flickr

When I was a little pre-teen at Dork Middle School For The Mentally Gifted in the early ’90s, anybody who was anybody (which was almost everybody, ’cause there were only 16 girls in my graduating class) read Lurlene McDaniel novels ravenously — stories which confirmed our suspicions that the world was a cruel, sad place, riddled with surprise tragedies and untimely deaths. It was the height of the “grunge” era and despite a relative shortage of “real problems” for most of us at that point, we were a fairly depressive bunch and therefore a ripe audience for McDaniel’s Lifetime-Movie-esque young adult books — according to McDaniel’s website, “everyone loves a good cry, and no one delivers heartwrenching stories like Lurlene McDaniel.” Excellent! We loved crying! We loved romanticized potentially-dying heroines surrounded by soft breezes who spent agonizing hours staring in the mirror wondering how their hair would look after chemo!

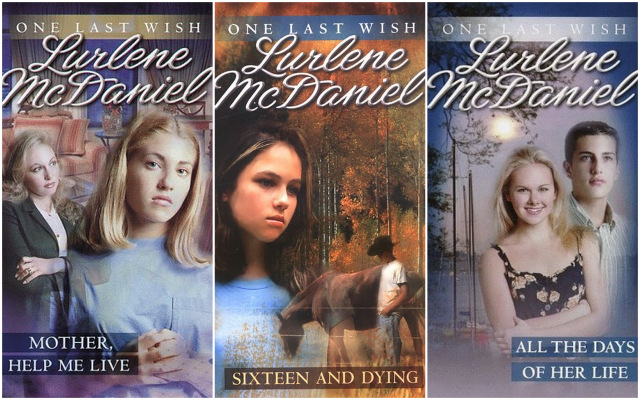

McDaniel hasn’t slowed down since the 80’s and 90’s, she’s now written over 50 books about “kids who face life-threatening illnesses, who sometimes do not survive.” Sample titles include: She Died Too Young, Sixteen and Dying, Please Don’t Let Him Die, The Girl Death Left Behind, Letting Go Of Lisa, When Happily Ever After Ends, and Goodbye Doesn’t Mean Forever. Somebody, usually a healthy happy popular teenager, develops a life-threatening medical condition, and then they either get better or die. Usually they get a boyfriend first. Here’s just a handfull of McDaniel’s book descriptions:

A change is coming, April Lancaster’s fortune cookie reads. Be prepared. But how could she be prepared for the news that she has an inoperable brain tumor?

Sixteen-year-old Kara Fischer has cystic fibrosis and only months to live. But the close-knit bond she develops with Vince, who also has the disease, helps her come to terms with her own illness. Given one last wish, Kara wonders if miracles could really happen.

Jessica McMillian and Jeremy Travino are a perfect couple. But now Jessica has been diagnosed as having kidney failure. She is on dialysis three days a week and is so depressed that she’s not sure she wants to live.

Julie Passanante Elman, a researcher at The University of Missouri-Columbia, recently conducted an examination of the many problematic aspects of Lurlene McDaniel’s world and the results of her deconstruction, “Nothing Feels As Real: Teen Sick-Lit, Sadness and the Condition of Adolescence,” appeared August 2012 issue of The Journal Of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies. A few weeks ago in The Daily Mail, journalist Tanith Carey used Elman’s work and a healthy helping of her own personal opinion to argue that “sick-lit” is a “disturbing phenomenon.” I found Carey’s argument — which posited the theory that “sick lit” began with Alice Sebold‘s The Lovely Bones, of all things (it’s not a young adult book, for starters, it’s also literary fiction), and is best exemplified by, of all things, the recent success of John Green‘s The Fault in Our Stars — baseless and misguided, but was intrigued by the quotes pulled from Elman’s paper. So I tracked it down and read it and that’s why we’re all here today, talking about why Baby Alicia is Dying and how to go about Letting Go Of Lisa.

Elman set out to critique “the ableist and sexist visions of disability and sexuality” in “teen sick-lit,” which she identifies as a sub-genre of the “YA problem novel.” The genre was booming in the 1980s, and that’s the decade of literature Elman has chosen to examine:

While YA problem novels of the 1970s often critiqued racism, sexism and homophobia, teen sick-lit of the following decade largely reaffirmed conservative political and sexual values and reconsolidated traditional heteronormative gender roles that had been “disrupted” by post-1968 identity movements.

My mother refused to buy me any Lurlene McDaniel books or let me borrow them from the library, so I resorted to borrowing them from friends. She just thought they were so unnecessarily morbid, you know? Like who wants to read about that shit? Tanith Carey is similarly disturbed by the inherent “morbidity” of the topic, but that’s where her similarities with my mother’s opposition ends.

See, Carey is offended by Sick Lit’s “sex and swearing” and the “distasteful” decision authors make by “using children with months to live to build dramatic tension.” But after reading Elman’s study and revisiting McDaniel’s work, it’s clear that “morbidity” was perhaps her novels’ least problematic aspect and that addressing chronic illness and death in young adult fiction isn’t inherently problematic at all. Far more disconcerting than her subject matter, and inconspicuously so, was McDaniel’s retro representation of girlhood and race as well as a remarkably ableist vision of disability for a series that claims to advocate for the disabled and ill children it smacks on its white-washed covers. It’s not that she talks about death, it’s how she talks about death.

Because ultimately her stories, while medically accurate, are wildly inaccurate to a frustrating degree regarding just about everything else.

Using McDaniel’s Dawn Rochelle series as a focal point, Elman describes how the novels reinforce damaging cultural ideas about the unattractiveness of ill or disabled bodies — the able-bodied teenagers’ rejection of ill or disabled teenagers is not only accepted, it’s more or less embraced. Often it seems that her characters, once in remission, habitually “trade up” to able-bodied partners. On the topic of Dawn Rochelle’s waning interest in her former boyfriend, Mike, now that Dawn is healthy and Mike still has a prosthetic leg: “Although he may have recovered from cancer, Mike’s disabled body can never be fully rehabilitated into (able) normality, and thus Mike could never represent a viable romantic interest for now-healthy Dawn within the story’s logic,” Elman writes. In the final novel, Dawn’s considering whether to go steady with Brent (who has cancer) and Jake (who does not), and Elman attests that “the series encourages Dawn to adhere to the logic of able-bodiedness by choosing Jake, who fully embodies the ‘good passport’ of the well.” This is in stark contrast to The Fault in Our Stars, in which Hazel’s oxygen tank, Augustus’ prosthetic leg and their friend Issac’s blindness are discussed frankly and the physical manifestations of Hazel’s illness have no affect whatsoever on Augustus’ desire for her.

“Teen sick-lit traffics in the most egregious and patronizing of cultural stereotypes about disability.”

Then there’s the compulsory heterosexuality thing. Like many novels geared towards teenagers, Sick Lit deals exclusively with traditional heterosexual romance. Elman notes that within the “compulsory able-bodiedness” social framework, “heterosexuality and health often seamlessly imply one another, while queerness and disability exist as epitomes of abnormality.” S.Chris Saad, in her study The Portayal of Male and Female Characters With Chronic Illnesses in Children’s Realistic Fiction, 1970-1994, found that 80.8% of the books studied featured chronically ill female main characters and that “when books were considered as a group, a pattern of sexism, racism and heterosexism emerged.”

Elman argues that sick lit was not unaffected by feminism so much as it was molded in direct opposition to the ideal of the women’s movement, demonstrating “an assiduous disavowal of liberal second-wave feminist ideals. McDaniel’s texts encourage and enforce adherence to traditional gender roles because it is part of ‘getting well.'” In the Dawn Rochelle novels, which Elman focuses on in her studies, she recalls the case of Marlee Hodge, Dawn’s cabinmate at cancer camp, a tomboy who is demonized as a troublemaker who terrorizes sick children.” Marlee’s rejection of “able-bodied and feminine standards of beauty” are used as evidence of an “unhealthy attitude” which won’t help her get well. Brent notes that: “Maybe it would help if she fixed herself up a little… she could make a little effort, you know, some makeup, covering her head.” Dawn tries repeatedly and fails to inspire Marlee to conform and don dresses and makeup, but when Marlee finally gives in and accepts a makeup, wig and outfit, she is applauded and, as Elman puts it, her “queer-crip resistiveness is tamed.”

Then there’s the race thing. Lurlene McDaniel’s protagonists are always white and usually Christian. Actually, and this is so obnoxiously racist that it’s almost a parody of itself — the only time people of color get involved is when somebody works with HIV-positive infants abandoned by their drug-addicted mothers or when the white protagonist takes a missionary trip to Uganda. I know! I KNOW.

It is these tired retro ascriptions to romantic tropes, gender-stereotyping and racial stereotyping that make McDaniel’s work so mockable for adults who once enjoyed the books as children. Forever Young Adult runs a series of Slurlene McDaniel Drunken Reviews, replete with a drinking game: “the only way to read these books is by contracting your own illness: liver failure! Because the best way to judge a book is by how many drinks you’ll need to get through it.”

In a Flashback Friday on the website Mamapop last summer, writer Molly recounts her childhood obsession with the series and Dawn Rochelle novels in particular:

Dawn Rochelle was beautiful, brave, and appeared to have a canopy bed. And I bet she kept a diary. And was in Key Club. And could barely sleep or hold down a job for the aura of romance that constantly enveloped her like Pigpen’s dust cloud. What? Oh yes, she also had cancer. And some hard-luck friends who were dropping like flies. But MYGAWD I wanted to be most-of-her in the worst way. I mean, her name was “Dawn Rochelle.” That is so fancy.

In a 2010 article for BUST Magazine, Marni Grossman argued that her adolescent attachment to these books was rooted in what she refers to as Beth March Syndrome (after the Little Women character) — “the desire to be kind and patient and cheerful and then wilt beautifully and die. Or simply come close enough so that everyone finally appreciates you.” It’s a spot-on analysis and perfectly encapsulates why young adults actually wanted to be these sick girls, despite the fact that there is absolutely nothing awesome about leukemia.

All girls are susceptible to Beth March syndrome, because we’re taught that suffering is a woman’s most noble role, and bearing the wrath of a terminal illness lends an innate goodness to the sufferer. In literature, men go to war to become heroes, achieving immortality through great acts, while women earn their place by courageously battling illness before graciously dying. I envied the girls in McDaniel’s books, not in spite of their ailments but because of them. Dying girls get the last laugh. They are loved and cherished, and they are, above all, good—even if they aren’t. Because you can’t really talk trash about a girl on her deathbed.

I’d argue that it’s McDaniel and her imitators specifically who inspire this response, but not all young adult novelists who address these themes. I mean, do McDaniel’s books offer actual comfort to ill children and their friends/families, or are they strictly voyeuristic? Although McDaniel was inspired to tackle these topics after her son was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes, I found that as soon as actual tragedy visited my own life, my interest in reading her fabricated tomes vanished instantly. Lurlene’s tragedies became sanitized, inaccurate and cloying reminders of my own pain rather than what they’d been before: doors into distant romantic places I’d heard about but not yet visited. I mean, The Boxcar Children seems like so much fun until you’re genuinely unable to find affordable housing.

I think I was possibly drawn to these books because I felt like something was wrong with me too but nobody could see it. I think a lot of teenagers feel that way. But if I was sick like Dawn Rochelle then everybody would know, and they’d all be nice to me and bring me cards and flowers, and I would seem prettier after all the doctor stuff because of how horrid I’d looked throughout treatment. So I think Carey has it all wrong when she quotes a child psychologist who hopes “let’s hope publishers do have young people’s interests at heart – and they are not selling books by sensationalising children’s suffering.” It’s not the sensationalizing that’s the problem with Lurlene McDaniel, it’s the romanticizing, and the prehistoric and repressive social conventions she employs to successfully do so, generally at the expense of anything remotely empowering.

Which is why ultimately comparing Sixteen and Dying to The Fault in Our Stars is like comparing Taylor Swift to Ani DiFranco or the new 90210 to My So-Called Life — and lumping books like those books into the same category suggests a prioritization of topic and plot over sentiment and context. Elman points out that Lurlene McDaniel’s bookmark slogans (“nothing feels as real as a Lurlene McDaniel book”) “suggest McDaniel’s books, and others like them, conjure a relationship between ‘realness’ and emotional intensity in which sadness connotes authenticity.” Unfortunately for the longevity of McDaniel’s position in her readers’ hearts, we all learn eventually that the only thing that connotes authenticity is actual authenticity. Whereas the Lurlene McDaniel cannon relies solely on the depressive weight of its plot to drive the story forward, books like The Fault in Our Stars rely on authentic characters, a healthy sense of humor and a dedication to honesty, even when it’s unpretty.

“While the Twilight series and its imitators are clearly fantasy, these books don’t spare any detail of the harsh realities of terminal illness, depression and death,” Tanith Carey writes in a critical sentence that explicitly misses the point in the most illustrative way possible. What we take away from a book is rarely the meat of it — the vampires, the cancer, the AIDS — but the subtext, what’s underneath it all, the messages about what girls should want, what we should be, who deserves love and who can’t have it. Because the truth is that children do, in fact, suffer, and it’s only natural that children are curious about illness and death and they either already are, or soon will be, grappling with it in their own lives. The pain demands to be felt, as it is written in The Fault of Our Stars. And there doesn’t need to be anything sick about that.